The Intriguing Flow Behavior of Soft Materials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Tribute to Jean Perrin

A TRIBUTE TO JEAN PERRIN l Henk Kubbinga – University of Groningen (The Netherlands) – DOI: 10.1051/epn/2013502 Nineteenth century's physics was primarily a molecular physics in the style of Laplace. Maxwell had been guided by Laplace’s breathtaking nebular hypothesis and its consequences for Saturn. Somewhat later Van der Waals drew upon his analysis of capillarity. The many textbooks of Biot perpetuated the molecularism involved in all this. Jean Perrin, then, proposed a charmingly simple proof for the well-foundedness of the molecular theory (1908). 16 EPN 44/5 Article available at http://www.europhysicsnews.org or http://dx.doi.org/10.1051/epn/2013502 JEAN PERRIN FEATURES ean [Baptiste] Perrin enrolled in 1891 at the Ecole and Robert Koch and fancied a state of science in which b P.16: Normale Supérieure de Paris, the nursery of France’s the microscope had not yet been invented. In such a situ- Saturn (with Titan) edge-on as viewed academic staff. The new ‘normalien’ came from Lyon ation Pasteur and Koch—let’s say, medical science in by the Hubble and had passed a typically French parcours: primary general—might have concluded all the same that con- Telescope (2012; Jschool and collège ‘en province’, lycée at Paris. The ‘nor- tagious diseases were caused by invisibly small living courtesy: NASA). maliens’ of the time were left-winged politically, but wore beings which infect a victim and set out immediately to uniforms, though, and despised their Sorbonne fellow multiply, before attacking subsequent victims etc. Effec- students. Mathematics made the difference; Perrin had tive countermeasures might have been developed in that passed without any trouble. -

The Discovery of Subatomic Particles

The Discovery of Subatomic Particles Steven Weinberg I. W. H . Freeman and Co mpa ny NE W Y ORK Staff and students at the Cavendish Laboratory, 1933 . Fourth row: J. K. Roberts, P. Harteck, R. C. Evans, E. C. Childs, R. A. Smith, Top row: W. ]. Henderson , W. E. Dun canson, P. Wright, G. E. Pringle, H. Miller. G. T. P. Tarr ant , L. H. Gray, j . P. Gort, M. L. Oliphant , P. I. Dee, ]. L. Pawsey, Second row: C. B. O. Mohr, N. Feath er, C. W. Gilbert , D.Shoenberg, D. E. Lea, C. £. Wynn-Williams. R. Witty, - -Halliday, H . S. W. Massey, E.S. Shire. Seated row: - - Sparshotr, J. A.Ratcliffe, G. Stead, J. Chadwick, G. F. C. Searle, Third row : B. B. Kinsey, F. W. Nicoll, G. Occhialini, E. C. Allberry, B. M. Crowt her, Professor Sir J. J. Thomson, Professo r Lord Ruth erford, Professor C. T. R. Wilson, B. V. Bowden, W. B. Lewis, P. C. Ho, E. T. S. Walton, P. W. Burbidge, F. Bitter. C. D. Ellis, Professor Kapirza, P. M. S. Blackett , - - Davies. 13 2 The Discovery of the Electron This century has seen the gradual realization that all matter is composed of a' f~w type s of elementary particles-tiny units that apparently cannot be subdi vided further. The list of elementary particle types has changed many times dunng the century, as new particles have been discovered and old ones have been found to be composed of more elementary constituents. At latest count there are some sixteen known types of elementary particles. -

Avogadro's Constant

Avogadro's Constant Nancy Eisenmenger Question Artem, 8th grade How \Avogadro constant" was invented and how scientists calculated it for the first time? Answer What is Avogadro's Constant? • Avogadros constant, NA: the number of particles in a mole • mole: The number of Carbon-12 atoms in 0.012 kg of Carbon-12 23 −1 • NA = 6:02214129(27) × 10 mol How was Avogadro's Constant Invented? Avogadro's constant was invented because scientists were learning about measuring matter and wanted a way to relate the microscopic to the macroscopic (e.g. how many particles (atoms, molecules, etc.) were in a sample of matter). The first scientists to see a need for Avogadro's constant were studying gases and how they behave under different temperatures and pressures. Amedeo Avogadro did not invent the constant, but he did state that all gases with the same volume, pressure, and temperature contained the same number of gas particles, which turned out to be very important to the development of our understanding of the principles of chemistry and physics. The constant was first calculated by Johann Josef Loschmidt, a German scientist, in 1865. He actually calculated the Loschmidt number, a constant that measures the same thing as Avogadro's number, but in different units (ideal gas particles per cubic meter at 0◦C and 1 atm). When converted to the same units, his number was off by about a factor of 10 from Avogadro's number. That may sound like a lot, but given the tools he had to work with for both theory and experiment and the magnitude of the number (∼ 1023), that is an impressively close estimate. -

Lesson 37: Thomson's Plum Pudding Model

Lesson 37: Thomson's Plum Pudding Model Remember back in Lesson 18 when we looked at trapping moving particles in a circular path using a magnetic field? • In this lesson we look at how using this type of set up eventually helped physicists start to figure out the nature of the atom. Early Theories about Atoms In 1803 John Dalton presented his theory that the elements of the periodic table were made of atoms. • The main reason he was proposing this idea was to be able to explain the chemistry that he was studying. • Dalton believed that atoms were solid pieces of matter that could not be broken down any further. ◦ This is why his model is often referred to as the Solid Sphere Model. • Although Dalton's model was able to explain the way he saw chemical reactions working, he was unable to really prove that matter was made up of these atoms, or how chemical bonding could happen between them. During the late 1800's experiments with cathode ray tubes (CRTs) were starting to The negative give the first glimpses into what an atom might be. electrode is referred ● A cathode ray tube is just a vacuum tube with two electrodes at the ends. to as the cathode. That's the reason ○ When a really high voltage is applied, mysterious “cathode rays” this is called a moved from the negative electrode to the positive electrode. cathode ray tube. ○ Sometimes you could see a glow at the opposite end of the tube when the tube was turned on. ● William Crookes used a really high quality cathode ray tube in 1885. -

Nobel Prizes in Physics Closely Connected with the Physics of Solids

Nobel Prizes in Physics Closely Connected with the Physics of Solids 1901 Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, Munich, for the discovery of the remarkable rays subsequently named after him 1909 Guglielmo Marconi, London, and Ferdinand Braun, Strassburg, for their contributions to the development of wireless telegraphy 1913 Heike Kamerlingh Onnes, Leiden, for his investigations on the properties of matter at low temperatures which lead, inter alia, to the production of liquid helium 1914 Max von Laue, Frankfort/Main, for his discovery of the diffraction of X-rays by crystals 1915 William Henry Bragg, London, and William Lawrence Bragg, Manchester, for their analysis of crystal structure by means of X-rays 1918 Max Planck, Berlin, in recognition of the services he rendered to the advancement of Physics by his discovery of energy quanta 1920 Charles Edouard Guillaume, Sèvres, in recognition of the service he has rendered to precise measurements in Physics by his discovery of anoma- lies in nickel steel alloys 1921 Albert Einstein, Berlin, for services to Theoretical Physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect 1923 Robert Andrews Millikan, Pasadena, California, for his work on the ele- mentary charge of electricity and on the photo-electric effect 1924 Manne Siegbahn, Uppsala, for his discoveries and researches in the field of X-ray spectroscopy 1926 Jean Baptiste Perrin, Paris, for his work on the discontinuous structure of matter, and especially for his discovery of sedimentation equilibrium 1928 Owen Willans Richardson, London, for his work on the thermionic phe- nomenon and especially for his discovery of the law named after him 1929 Louis Victor de Broglie, Paris, for his discovery of the wave nature of electrons 1930 Venkata Raman, Calcutta, for his work on the scattering of light and for the discovery of the effect named after him © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2015 199 R.P. -

The Theory of Brownian Motion: a Hundred Years’ Anniversary Paweł F

52 SPECIAL ISSUE, Spring 2006 The theory of Brownian Motion: A Hundred Years’ Anniversary Paweł F. Góra Marian Smoluchowski Institute of Physics Jagellonian University, Cracow, Poland The year 1905 was truly a miracle year, annus mirabilis, in theoretical physics. Albert Einstein published four im- portant papers that year: Two papers laying foundations for the Special Theory of Relativity, one explaining the photo- electric effect that would win Einstein the 1921 Nobel Prize in physics, and one explaining the mechanism of Brownian motion1. An independent explanation of this last phenome- non was published the following year by a Polish physicist Marian Smoluchowski2. An explanation of the origin and Marian Smoluchowski properties of Brownian motion was a solution to a nearly 80 (1872–1917) years old puzzle, a remarkable feat, but nobody expected it to be a major breakthrough that would reshape the whole physics. This was, how- ever, the case and we will try to explain why. Brownian motion takes its name after a Scottish botanist, Robert Brown. Brown was a highly respected man in his time, not, however, for the discovery that he is now famous for, but for his classification of the plants of the New World. It was during this research that Brown noticed in 1827 that pollen in water suspension which he examined in his microscope displayed a very rapid, highly irregular, zigzag motion. Such motions had been observed even prior to Brown, but only in organic molecules, and their origin was delegated to some mysterious “vital Robert Brown (1773–1858) force” characteristic of living matter. Brown was not satisfied with this explanation, which could possibly fit the living pollen. -

111 Years of Brownian Motion

Soft Matter View Article Online TUTORIAL REVIEW View Journal | View Issue 111 years of Brownian motion a b a Cite this: Soft Matter, 2016, Xin Bian,* Changho Kim and George Em Karniadakis* 12, 6331 We consider the Brownian motion of a particle and present a tutorial review over the last 111 years since Einstein’s paper in 1905. We describe Einstein’s model, Langevin’s model and the hydrodynamic models, with increasing sophistication on the hydrodynamic interactions between the particle and the fluid. In Received 18th May 2016, recent years, the effects of interfaces on the nearby Brownian motion have been the focus of several Accepted 29th June 2016 investigations. We summarize various results and discuss some of the controversies associated with new DOI: 10.1039/c6sm01153e findings about the changes in Brownian motion induced by the interface. www.rsc.org/softmatter 1 Introduction dust in a fluid. However today, its theory can be also applied to describe the fluctuating behavior of a general system interact- Soon after the invention of the microscope, the incessant and ing with the surroundings, e.g., stock prices. irregular motion of small grains suspended in a fluid had been It was not until 1905 that physicists such as Albert Einstein,3 observed. It was believed for a while that such jiggling motion William Sutherland,4 and Marian von Smoluchowski5 started to was due to living organisms. In 1827, the botanist Robert gain deep understanding about Brownian motion. While the Brown systematically demonstrated that any small particle existence of atoms and molecules was still open to objection, suspended in a fluid has such characteristics, even an Einstein explained the phenomenon through a microscopic inorganic grain.1 Therefore, the explanation for such motion picture. -

The Reason for Beam Cooling: Some of the Physics That Cooling Allows

The Reason for Beam Cooling: Some of the Physics that Cooling Allows Eagle Ridge, Galena, Il. USA September 18 - 23, 2005 Walter Oelert IKP – Forschungszentrum Jülich Ruhr – Universität Bochum CERN obvious: cooling and control of cooling is the essential reason for our existence, gives us the opportunity to do and talk about physics that cooling allows • 1961 – 1970 • 1901 – 1910 1961 – Robert Hofstadter (USA) 1901 – Wilhelm Conrad R¨ontgen (Deutschland) 1902 – Hendrik Antoon Lorentz (Niederlande) und Rudolf M¨ossbauer (Deutschland) Pieter (Niederlande) 1962 – Lev Landau (UdSSR) 1903 – Antoine Henri Becquerel (Frankreich) 1963 – Eugene Wigner (USA) und Marie Curie (Frankreich) Pierre Curie (Frankreich) Maria Goeppert-Mayer (USA) und J. Hans D. Jensen (Deutschland) 1904 – John William Strutt (Großbritannien und Nordirland) 1964 – Charles H. Townes (USA) , 1905 – Philipp Lenard (Deutschland) Nikolai Gennadijewitsch Bassow (UdSSR) und 1906 – Joseph John Thomson (Großbritannien-und-Nordirland) Alexander Michailowitsch Prochorow (UdSSR) und 1907 – Albert Abraham Michelson (USA) 1965 – Richard Feynman (USA), Julian Schwinger (USA) Shinichiro Tomonaga (Japan) 1908 – Gabriel Lippmann (Frankreich) 1966 – Alfred Kastler (Frankreich) 1909 – Ferdinand Braun (Deutschland) und Guglielmo Marconi (Italien) 1967 – Hans Bethe (USA) 1910 – Johannes Diderik van der Waals (Niederlande) 1968 – Luis W. Alvarez (USA) 1969 – Murray Gell-Mann (USA) 1970 – Hannes AlfvAn¨ (Schweden) • 1911 – 1920 Louis N¨oel (Frankreich) 1911 – Wilhelm Wien (Deutschland) 1912 – Gustaf -

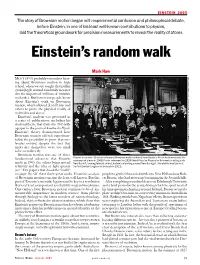

Einstein's Random Walk

EINSTEIN 2005 The story of Brownian motion began with experimental confusion and philosophical debate, before Einstein, in one of his least well-known contributions to physics, laid the theoretical groundwork for precision measurements to reveal the reality of atoms Einstein’s random walk Mark Haw MOST OF US probably remember hear- RCHIVES ing about Brownian motion in high A ISUAL school, when we are taught that pollen V grains jiggle around randomly in water EGRÈ due the impacts of millions of invisible S MILIO molecules. But how many people know about Einstein’s work on Brownian /AIP E OLVAY motion, which allowed Jean Perrin and S others to prove the physical reality of HYSIQUE P molecules and atoms? Einstein’s analysis was presented in a series of publications, including his NTERNATIONAL DE doctoral thesis, that started in 1905 with I NSTITUT a paper in the journal Annalen der Physik. , I Einstein’s theory demonstrated how OUPRIE Brownian motion offered experimen- C ENJAMIN talists the possibility to prove that mo- B lecules existed, despite the fact that molecules themselves were too small to be seen directly. Brownian motion was one of three fundamental advances that Einstein Physics in motion – Einstein’s theory of Brownian motion allowed Jean Baptiste Perrin to demonstrate the existence of atoms in 1908. Perrin, who won the 1926 Nobel Prize for Physics for this work, is sitting sixth made in 1905, the others being special from the left, leaning forward, while Einstein is standing second from the right. This picture was taken at relativity and the idea of light quanta the first Solvay Congress in Brussels in 1911. -

Éloge De Jean Perrin \(1870-1942\)

Éloge de Jean Perrin (1870-1942) Henk Kubbinga ([email protected]) Université de Groningen, Bilderdijklaan 109, NL-9721-PT, Groningen (Pays-Bas) Membre du groupe d’histoire de la physique de la Société européenne de Physique (EPS) Histoire des sciences 4 La physique de Laplace était Jean [Baptiste] Perrin entre en 1891 à essentiellement moléculaire. l’École normale supérieure de Paris. Le jeune normalien avait fait un parcours Grâce à Maxwell, Boltzmann typiquement français : école primaire et et Van der Waals, cette physique collège en province, lycée à la capitale. L’École était fameuse pour son gauchisme, devint la base même de la mais ses élèves n’en portaient pas moins thermodynamique moléculaire des uniformes et s’enorgueillissaient de leurs traditions, tout en méprisant leurs collègues statistique. Ce fut Jean Perrin de la Sorbonne. Les mathématiques faisaient qui proposa, en 1908, une la différence ; Perrin n’y avait aucun pro- Jean Perrin, tableau réalisé par sa fi lle Aline Lapique-Perrin blème. Il choisit Marcel Brillouin (1854- (vers 1926 ; huile sur toile, 34 x 37 cm, collection de la preuve expérimentale des 1948) comme directeur d’études, le même famille Perrin). plus élégantes du bien-fondé qui avait introduit, en France, les célèbres Vorlesungen über Gastheorie de Ludwig Un aller-retour : de cette théorie. Boltzmann. de la physico-chimie à la physique Tout en préparant son doctorat d’État ès Jean Perrin a aussi joué sciences, Perrin débute en 1895 sur la À l’ENS, Perrin est chargé d’un nouvel un rôle majeur dans la politique scène internationale, en expérimentateur enseignement : un cours de physico-chimie, extrêmement doué, avec la publication science inaugurée très récemment par scientifi que de la France des d’une démonstration convaincante du fait Van’t Hoff, Ostwald et Arrhenius. -

Perrin.Pdf Please Take Notice Of: (C)Beneke

URL: http://www.uni-kiel.de/anorg/lagaly/group/klausSchiver/perrin.pdf Please take notice of: (c)Beneke. Don't quote without permission. Jean Baptiste Perrin (30.09.1870 Lille - 17.04.1942 New York) Kolloidwissenschaftler, Nobelpreisträger Klaus Beneke Institut für Anorganische Chemie der Christian-Albrechts-Universität der Universität D-24098 Kiel [email protected] Auszug und ergänzter Artikel (Oktober 2006) aus: Klaus Beneke Biographien und wissenschaftliche Lebensläufe von Kolloidwissenschaftlern, deren Lebensdaten mit 1995 in Verbindung stehen. Beiträge zur Geschichte der Kolloidwissenschaften, VII Mitteilungen der Kolloid-Gesellschaft, 1998, Seite 108-110 Verlag Reinhard Knof, Nehmten ISBN 3-934413-01-3 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis Seite Inhaltsverzeichnis 2 Leben und Werk von Jean Perrin 3 13 Kurzlebenslauf von Richard Zsigmondy (1865 - 1929) 4-5 Kurzlebenslauf von Marian von Smoluchowski (1872 - 1917) 5-6 Brownsche Molekularbewegung 6 Robert Brown (1773 - 1858) 6 Kurzlebenslauf von Jean Frédéric Joliot-Curie (1900 - 1958) 8-9 Literatur 13 3 Jean Baptiste Perrin (30.09.1870 Lille - 17.04.1942 New York) Kolloidwissenschaftler, Nobelpreisträger Der Vater, Sohn armer Landwirte, starb im deutsch-französischen Krieg (1870/71). Jean Baptiste Perrin wuchs mit seiner Mutter und zwei Schwestern auf und besuchte Schulen in Lyon und Paris. Nach einem Dienstjahr in der Französischen Armee trat er 1891 in die École Normale Supérieure ein und studierte Physik in Lyon. Sein Lehrer Louis Marcel Brillouin (19.12.1854 Melle - 16.06.1948 Paris) machte ihn dort mit den Auffassungen zum Louis Marcel Brillouin diskontinuierlichen Aufbau der Materie und den unterschiedlichen Ansichten Wilhelm Ostwald (02.09.1853 Riga - 04.04. 1932 Leipzig) bzw. -

On the 150Th Birthday of Max Planck

On the 150th Birthday of Max Planck: On Honesty Towards Nature by Caroline Hartmann Nature and the universe act according to lawfully knowable rules, not by the accidents of statistics and probability. he great physicist Max Planck would have been 150 years old on April 23, 2008. In Tdiscovering the correct equation for the description of heat radiation (the famous Radia- tion formula), he blazed a new trail for physics. His formula contains the postulation E = hn, that is, that energy is available in so-called quanta. It is thanks to Planck’s integrity and strength of character that this true explanation of heat radia- tion prevailed, because the discussion at that time was anything but honest, above all when one considered the methods of a Niels Bohr. For, the Copenhagen interpretation, the uncertainty principle, and quantum mechanics are pure mathematical-statistical interpretations. Almost all scientists at the time fell in with the mathe- matical euphoria, without exact knowledge of the true physical processes. First one had to have a System, then came the discoveries. Already as a young physicist Max Planck had found that the world of established, so-called classical, physics, as represented by famous “big-name” professors like Robert Clausius, Hermann von Helmholtz, and others, suffered from some problems with the understanding of various natural phenomena, and above all with the acceptance of new and far-reaching ideas. In his prize-winning work of 1887, “Das Prinzip der Erhaltung der Energie” (The Principle of the Conservation of Energy), submitted for a contest sponsored by the Göttingen philosophy depart- ment, Planck had mentioned the work of Robert Mayer, the discoverer of the mechanical equiva- lent of heat, and especially his explanation of Presse- und Informationsamt der Bundesregierung-Bundesbildstelle the phenomenon of heat.