The Limits of Radical Parties in Coalition Foreign Policy: Italy, Hijacking, and the Extremity Hypothesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rifondazione Comunista Dallo Scioglimento Del PCI Al “Movimento Dei Movimenti”

C. I. P. E. C., Centro di iniziativa politica e culturale, Cuneo L’azione politica e sociale senza cultura è cieca. La cultura senza l’azione politica e sociale è vuota. (Franco Fortini) Sergio Dalmasso RIFONDARE E’ DIFFICILE Rifondazione comunista dallo scioglimento del PCI al “movimento dei movimenti” Quaderno n. 30. Alla memoria di Ludovico Geymonat, Lucio Libertini, Sergio Garavini e dei/delle tanti/e altri/e che, “liberamente comunisti/e”, hanno costruito, fatto crescere, amato, odiato...questo partito e gli hanno dato parte della loro vita e delle loro speranze. Introduzione Rifondazione comunista nasce nel febbraio del 1991 (non adesione al PDS da parte di alcuni dirigenti e di tanti iscritti al PCI) o nel dicembre dello stesso anno (fondazione ufficiale del partito). Ha quindi, in ogni caso, compiuto i suoi primi dieci anni. Sono stati anni difficili, caratterizzati da scadenze continue, da mutamenti profondi del quadro politico- istituzionale, del contesto economico, degli scenari internazionali, sempre più tesi alla guerra e sempre più segnati dall’esistenza di una sola grande potenza militare. Le ottimistiche previsioni su cui era nato il PDS (a livello internazionale, fine dello scontro bipolare con conseguente distensione e risoluzione di gravi problemi sociali ed ambientali, a livello nazionale, crescita della sinistra riformista e alternanza di governo con le forze moderate e democratiche) si sono rivelate errate, così come la successiva lettura apologetica dei processi di modernizzazione che avrebbero dovuto portare ad un “paese normale”. Il processo di ricostruzione di una forza comunista non è, però, stato lineare né sarebbe stato possibile lo fosse. Sul Movimento e poi sul Partito della Rifondazione comunista hanno pesato, sin dai primi giorni, il venir meno di ogni riferimento internazionale (l’elaborazione del lutto per il crollo dell’est non poteva certo essere breve), la messa in discussione dei tradizionali strumenti di organizzazione (partiti e sindacati) del movimento operaio, la frammentazione e scomposizione della classe operaia. -

Md the Vatican

md the Vatican 1kFTERA BITTERLY FOUGHT election campaign, the center- rignt coalition headed by Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi narrowly lost to a center-left bloc headed by Romano Prodi in general elections held April 9—10. Berlusconi refused to concede defeat for several days, but Prodi managed to form a government and was sworn in the following onth. While many Italian Jews distrusted some of the leftist parties al- vith Prodi because of their pro-Palestinian stance, others countered Berlusconi's "House of Freedoms" coalition had included small far- parties directly linked to fascism. Italian president Carlo D'Azeglio Ciampi completed his seven-year i in May and was replaced by Giorgio Napolitano, a longtime leftist the Middle East oule Last issues had a powerful impact on Italian politics and for- policy throughout the year. January, Prime Minister Berlusconi called Israeli prime minister Sharon's illness and incapacitation "very painful on the human and absolutely negative on the political level." In February, the gov- nt's minister for reforms, Roberto Calderoli, was forced to resign eing seen on television wearing a T-shirt bearing copies of the Dan- rtoons of the prophet Mohammed that had triggered bloody riots 'eral countries. Calderoli, a member of the far-right Northern ,saidhe wore the shirt to express "solidarity with all those who een struck by the blind violence of religious fanaticism." His tele- appearance triggered anti-Italian protests in Libya, where thou- tormed the Italian consulate in Benghazi. I regarded the government of Prime Minister Berlusconi as one )est friends in Europe, and its fall gave cause for concern. -

Modello Per Schede Indice Repertorio

PROCEDIMENTI RELATIVI AI REATI PREVISTI DALL'ARTICOLO 96 DELLA COSTITUZIONE Trasmissione di decreti di archiviazione: 2 Domande di autorizzazione a procedere in giudizio ai sensi dell'articolo 96 della costituzione: 4 TRASMISSIONE DI DECRETI DI ARCHIVIAZIONE atti relativi ad ipotesi di responsabilità nei confronti di Lamberto Dini, nella sua qualità di Ministro degli affari esteri pro tempore e di altri, sed. 13; atti relativi ad ipotesi di responsabilità nei confronti di Oscar Luigi Scalfaro, nella sua qualità di Ministro dell'interno pro tempore e di altri, sed. 16; atti relativi ad ipotesi di responsabilità nei confronti di Gianni De Michelis, nella sua qualità di Vice Presidente del Consiglio e Ministro degli affari esteri pro tempore e di altri, sed. 94; atti relativi ad ipotesi di responsabilità nei confronti di Edoardo Ronchi, nella sua qualità di Ministro dell'ambiente pro tempore, sed. 94; atti relativi ad ipotesi di responsabilità nei confronti di Roberto Castelli, nella sua qualità di Ministro della giustizia, sed. 94; atti relativi ad ipotesi di responsabilità nei confronti di Ottaviano Del Turco, nella sua qualità di Ministro dell'economia e delle finanze pro tempore, sed. 96; atti relativi ad ipotesi di responsabilità nei confronti di Roberto Castelli, nella sua qualità di Ministro della giustizia, sed. 113; atti relativi ad ipotesi di responsabilità nei confronti di Giovanni Fontana, nella sua qualità di Ministro dell'agricoltura e delle foreste pro tempore e di altri, sed. 130; atti relativi ad ipotesi di responsabilità nei confronti di Gianni De Michelis, nella sua qualità di Ministro del lavoro pro tempore, sed. 134; atti relativi ad ipotesi di responsabilità nei confronti di Giuliano Amato, nella sua qualità di Presidente del Consiglio pro tempore, Piero Barucci, nella sua qualità di Ministro del tesoro pro tempore, e Francesco Reviglio della Veneria, nella sua qualità di Ministro del bilancio e programmazione economica pro tempore, sed. -

States of Emergency Cultures of Revolt in Italy from 1968 to 1978

States of Emergency Cultures of Revolt in Italy from 1968 to 1978 ----------------♦ --------------- ROBERT LUMLEY V VERSO London • New York First published by Verso 1990 ! © R o bert Lumley 1990 All rights reserved Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1V 3HR USA: 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001-2291 Verso is the imprint of New Left Books British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Lumley, Robert States of emergency : cultures of revolt in Italy from 1968 to 1978. 1. Italy. Social movements, history I. Title 30 3 .4 '8 4 ISBN 0-86091-254-X ISBN 0-86091-969-2 pbk Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lumley, Robert, 1951 — States of emergency : cultures of revolt in Italy ( O 1 9 6 8 -1 9 7 8 / Robert Lumley. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-86091-254-X. - ISBN 0-86091-969-2 (pbk.) 1. Italy—Politics and government-1945-1976. 2. Italy—Politics and government-1976- 3. Students-ltaly-Political activity- History-20th century. 4. Working class-ltaly-Political activity-History-20th century. 5. Social movements-italy- History-20th century. 6. Italy-Social conditions-1945-1976. 7. Italy-Social conditions-1976- I. Title. DG577.5.L86 1990 945.092'6-dc20 Typeset in September by Leaper &C Gard Ltd, Bristol Printed in Great Britain by Bookcraft (Bath) Ltd acknowledgements The bulk of this book was first written as a Ph.D. thesis (finished in 1983 with the title ‘Social Movements in Italy, 1 9 6 8 -7 8 ’) at the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, at the University of Birmingham. -

Italian Political Parties and Military Operations Abroad

Network for the Advancement of Social and Political Studies (NASP) PhD Program in Political Studies (POLS) – 32nd Cohort PhD Dissertation “At the Water’s Edge?”: Italian Political Parties and Military Operations Abroad Supervisor PhD Candidate Prof. Fabrizio Coticchia Valerio Vignoli Director of the Course Prof. Matteo Jessoula Academic Year: 2018/2019 Index Tables and figures Acknowledgments Introduction Aim of the research…………………………………………………………………………... 1 The state of the art and contribution to the literature………………………………………… 3 Case selection: Italian parties and MOAs during the Second Republic……………………… 5 Data and methods…………………………………………………………………………….. 8 Structure of the thesis……………………………………………………………………….... 9 Chapter 1 – Political parties, foreign policy and Italy’s involvement in Military Operations Abroad Introduction………………………………………………………………………………....... 11 The domestic turn in International Relations………………………………………………… 12 Political Parties and foreign policy…………………………………………………………... 16 - Ideology and foreign policy………………………………………………………….. 17 - Coalition politics and foreign policy…………………………………………………. 20 - Parliament and war…………………………………………………………………… 23 Political parties and Military Operations Abroad in Italy during the Second Republic……… 26 - Italian political parties: from the First to the Second Republic………………………. 26 - Italian foreign policy in the Second Republic: between continuity and change……… 30 - Italy and Military Operations Abroad……………………………………………….... 33 Conclusions…………………………………………………………………………………… 41 Chapter 2 – Explaining -

GIPE-011462.Pdf

<C~A\§§ <C®NF~n<CT lIN IITA\~Y o KARL WALTER. APPENDIX (FIIr on int.rpr.tatilJll ".! the present validity and significantt of the LolHrur Charter, Set page 38.) THE LABOUR CHARTER (1927) THE CORPORATIVE STATE AND ITS ORGANISATION I The Italian nation i. an organism whose life, aims and means are greater in power and duration than those of the individuals and groups of which it is composed. It is a moral, political and econo mic unity, which is integrally realised in the Fascist State. H Labour, in all its forms of organisation and enterprise, intel lectual, technical, manual, is a social duty. By that tide alone it comes under the guardianship of the State. From the national point of view the complex of production is unitarian; its objectives are unitarian and are summarised in the welfare of the individual and the development of national strength. III Trade union or professional organisation is voluntary. But only the trade union or association which is legally recognised and regulated by the State has the right legally to represent that category of workers or employers for which it is constituted, to safeguard their interests in respect of the state and other profes sional institutions, to enter into collective labour contracts obli gatory for the whole of that category, to exact contributions from them, and on their behalf to exercise the delegated powers of a public body. IV The collective labour contract is the expression of solidarity between the various factors of production, through conciliation of 129 13° AppmdiJt the conHicting interests of employers and employees, subordinated to the higher interests of production. -

Cannavaaaa Aeur-Tm-S-Farewell A1282.Pdf (

CannavòâEuros"s farewell http://internationalviewpoint.org/spip.php?article1282 Italy CannavòâEuros"s farewell - IV Online magazine - 2007 - IV390 - June 2007 - Publication date: Saturday 16 June 2007 Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine - All rights reserved Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine Page 1/4 CannavòâEuros"s farewell Rome. On Saturday afternoon the honourable deputy Salvatore Cannavò, at the head of the demonstration protesting against George W. Bush, said something like: âEurosoeI have a letter in my pocket but I still want to wait a few hoursâEuros¦âEuros [http://internationalviewpoint.org/IMG/jpg/SinistraCriticademo1.jpg] âEurosoeAnd now the few hours have passed, indeedâEuros . Precisely. âEurosoeAnd yes, in sum I spoke of my relationship with Rifondazione Comunista. A relationship that, unhappily, is brokenâEuros Broken? ItâEuros"s a rather vague term, Mr Deputy. âEurosoeI mean that so far as I am concerned, I consider that the experience of Rifondazione has come to its end, that it is over. Naturally, I should in any case discuss that with the comrades of my currentâEuros¦ âEurosoe. The âEurosoeCritical LeftâEuros . âEurosoeIn September we will hold our first national conferenceâEuros . These words and projects could be a harsh blow for his party. âEurosoeLook, to be sincere, my relationship with the party has already profoundly changed following the expulsion of senator Turigliatto.âEuros It was indeed knownâEuros¦ âEurosoeI no longer participated, in reality, in the life of the party. I did not take part in its leadership and I was outside of the everyday life of the parliamentary group.âEuros And then on Saturday he found himself at the head of a demonstration. -

Composizione Del Governo D'alema (Circ. Conf.Le 20/2000)

Confederazione Generale Italiana dei Trasporti e della Logistica via Panama 62 - 00198 Roma - tel. 06.8559151 - fax 06.8415576 e-mail: [email protected] - http://www.confetra.com Roma, 24 gennaio 2000 CIRCOLARE N. 20/2000 OGGETTO: COMPOSIZIONE DEL NUOVO GOVERNO D’ALEMA. Si riporta la composizione del nuovo Governo D’Alema con riferimento ai Ministri e ai Sottosegretari di piu’ diretto interesse per i settori rappresentati dalla Confetra. Per ciascun nominativo viene indicato luogo e data di nascita, l’eventuale carica ricoperta nel precedente Governo nonche’, qualora trattasi di componente del Parlamento, partito di appartenenza e collegio elettorale. PRESIDENZA DEL CONSIGLIO Presidente: on. Massimo D’ALEMA (D.S.) Roma 1949 – Collegio di Casarano (Le) Sottosegretari: • dr. Enrico MICHELI Terni 1938 – Già Ministro dei Lavori Pubblici • dr. Marco MINNITI (D.S.) – Confermato - Reggio Calabria 1956 • on. Elena MONTECCHI (D.S.) – Confermata - Reggio Emilia 1954 – Collegio di Guastalla (Re) • on. Luciano CAVERI (U. Valdotaine) Aosta 1958 – Collegio di Aosta • on. Raffaele CANANZI (P.P.I.) Caulonia (Rc) – Collegio XI Circ.ne Campania 1 • on. Adriana VIGNERI (D.S) Treviso 1939 – Collegio VIII Circ.ne Veneto 2 • dr. Dario FRANCESCHINI (P.P.I.) Ferrara 1958 • sen. Stefano PASSIGLI Firenze 1938 – Collegio VI Pistoia MINISTERO DEI TRASPORTI Ministro: dr. Pierluigi BERSANI (D.S.) Bettola(Pc) 1951 – Già Ministro dell’Industria Sottosegretari: • on. Giordano ANGELINI (D.S.) – Confermato - Ravenna 1939 - Collegio di Ravenna-Cervia • on. Luca DANESE (UDEUR) – Confermato - Roma 1958 - Collegio circ.nale Lazio 2 • sen. Mario OCCHIPINTI (Dem) Scicli (Rg) 1954 – Collegio di Avola MINISTERO DELLE FINANZE Ministro: on. Vincenzo VISCO (D.S.) – Confermato - Foggia 1942 - Collegio di Perugia Sottosegretari: • on. -

The Left in Europe

ContentCornelia Hildebrandt / Birgit Daiber (ed.) The Left in Europe Political Parties and Party Alliances between Norway and Turkey Cornelia Hildebrandt / Birgit Daiber (ed.): The Left in Europe. Political Parties and Party Alliances between Norway and Turkey A free paperback copy of this publication in German or English can be ordered by email to [email protected]. © Rosa Luxemburg Foundation Brussels Office 2009 2 Content Preface 5 Western Europe Paul-Emile Dupret 8 Possibilities and Limitations of the Anti-Capitalist Left in Belgium Cornelia Hildebrandt 18 Protests on the Streets of France Sascha Wagener 30 The Left in Luxemburg Cornelia Weissbach 41 The Left in The Netherlands Northern Europe Inger V. Johansen 51 Denmark - The Social and Political Left Pertti Hynynen / Anna Striethorst 62 Left-wing Parties and Politics in Finland Dag Seierstad 70 The Left in Norway: Politics in a Centre-Left Government Henning Süßer 80 Sweden: The Long March to a coalition North Western Europe Thomas Kachel 87 The Left in Brown’s Britain – Towards a New Realignment? Ken Ahern / William Howard 98 Radical Left Politics in Ireland: Sinn Féin Central Europe Leo Furtlehner 108 The Situation of the Left in Austria 3 Stanislav Holubec 117 The Radical Left in Czechia Cornelia Hildebrandt 130 DIE LINKE in Germany Holger Politt 143 Left-wing Parties in Poland Heiko Kosel 150 The Communist Party of Slovakia (KSS) Southern Europe Mimmo Porcaro 158 The Radical Left in Italy between national Defeat and European Hope Dominic Heilig 166 The Spanish Left -

23-64-Volume Primo Tomo 5 Parte

SENATO DELLA REPUBBLICA CAMERA DEI DEPUTATI XIII LEGISLATURA Doc. XXIII n. 64 VOLUME PRIMO Tomo V Parte prima COMMISSIONE PARLAMENTARE D'INCHIESTA SUL TERRORISMO IN ITALIA E SULLE CAUSE DELLA MANCATA INDIVIDUAZIONE DEI RESPONSABILI DELLE STRAGI istituita con legge 23 dicembre 1992, n. 499, che richiama la legge 17 maggio 1988, n. 172 e successive modificazioni (composta dai senatori: Pellegrino, Presidente, Manca, Vice presidente, Palombo, Segretario, Bertoni, Caruso, Cioni, CoÁ, De Luca Athos, Dentamaro, Dolazza, Follieri, Giorgianni, Mantica, Mignone, Nieddu, Pace, Pardini, Piredda, Staniscia, Toniolli, Ventucci e dai deputati: Grimaldi, Vice presidente, Attili, Bielli, Cappella, Carotti, Cola, Delbono, Detomas, Dozzo, FragalaÁ, Gnaga, Lamacchia, Leone, Marotta, Miraglia del Giudice, Nan, Ruzzante, Saraceni, Taradash, Tassone) Decisioni adottate dalla Commissione nella seduta del 22 marzo 2001 in merito alla pubblicazione degli atti e dei documenti prodotti e acquisiti ELABORATI PRESENTATI DAI COMMISSARI Comunicate alle Presidenze il 26 aprile 2001 13 - PAR - INC - 0064 - 0 TIPOGRAFIA DEL SENATO (1200) Senato della Repubblica± III ± Camera dei deputati XIII LEGISLATURA ± DISEGNI DI LEGGE E RELAZIONI - DOCUMENTI INDICE VOLUME I, TOMO V PARTE PRIMA (*) Lettere di trasmissione ai Presidenti delle Camere . Pag. V Decisioni adottate dalla Commissione nella seduta del 22 marzo 2001........................... »IX Elenco degli elaborati prodotti dai Commissari. »XI Legge istituitiva e Regolamento interno. ......... »XV Elenco dei componenti . ..................... » XXXVIII Per una rilettura degli anni Sessanta (sen. Mantica, on. FragalaÁ) ................. » 1 L'ombra del KGB sulla politica italiana (on. Taradash, on. FragalaÁ, sen. Manca, sen. Man- tica) ................................... » 65 INDICE VOLUME I, TOMO V PARTE SECONDA (*) La dimensione sovranazionale del fenomeno eversivo in Italia (sen. Mantica, on. -

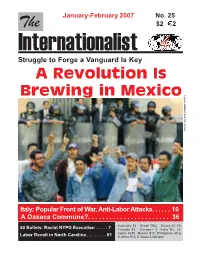

Internationalist Struggle to Forge a Vanguard Is Key a Revolution Is

January-February 2007 No. 25 The $2 2 Internationalist Struggle to Forge a Vanguard Is Key A Revolution Is Brewing in Mexico Times Addario/New Lynsey York Italy: Popular Front of War, Anti-Labor Attacks. 10 A Oaxaca Commune?. 36 Australia $4, Brazil R$3, Britain £1.50, 50 Bullets: Racist NYPD Execution . 7 Canada $3, Europe 2, India Rs. 25, Japan ¥250, Mexico $10, Philippines 30 p, Labor Revolt in North Carolina . 61 S. Africa R10, S. Korea 2,000 won 2 The Internationalist January-February 2007 In this issue... Mexico: The UNAM A Revolution Is Brewing in Mexico .......... 3 Strike and the Fight for Workers 50 Bullets: Racist NYPD Cop Execution, Revolution Again ........................................................ 7 March 2000 US$3 Mobilize Workers Power to Free Mumia For almost a year, tens of Abu-Jamal! .....................'--························ 9 thousands of students occupied the largest university Italy: Popular Front of Imperialist in Latin America, facing War and Anti-Labor Attacks .................... 10 repression by both the PAI government and the PAD Break Calderon's "Firm Hand" With opposition. This 64-page special supplement tells the Workers Struggle .................................. 15 story of the strike and documents the intervention State of Siege in Oaxaca, Preparations of the Grupo in Mexico City ....................................... 17 lnternacionalista. November 25 in Oaxaca: Order from/make checks payable to: Mundial Publications, Box 3321, Church Street Station, NewYork, New York 10008, U.S.A. Night of the Hyenas .............................. 20 Oaxaca Is Burning: Showdown in Mexico ........................... 21 Visit the League for the Fourth International/ Internationalist Group on the Internet The Battle of Oaxaca University ............. 23 http://www.internationalist.org A Oaxaca Commune? ..................... -

CHAPTER I – Bloody Saturday………………………………………………………………

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF JOURNALISM ITALIAN WHITE-COLLAR CRIME IN THE GLOBALIZATION ERA RICCARDO M. GHIA Spring 2010 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in Journalism with honors in Journalism Reviewed and approved by Russell Frank Associate Professor Honors Adviser Thesis Supervisor Russ Eshleman Senior Lecturer Second Faculty Reader ABSTRACT At the beginning of the 2000s, three factories in Asti, a small Italian town, went broke and closed in quick succession. Hundreds of men were laid off. After some time, an investigation mounted by local prosecutors began to reveal what led to bankruptcy. A group of Italian and Spanish entrepreneurs organized a scheme to fraudulently bankrupt their own factories. Globalization made production more profitable where manpower and machinery are cheaper. A well-planned fraudulent bankruptcy would kill three birds with one stone: disposing of non- competitive facilities, fleecing creditors and sidestepping Italian labor laws. These managers hired a former labor union leader, Silvano Sordi, who is also a notorious “fixer.” According to the prosecutors, Sordi bribed prominent labor union leaders of the CGIL (Italian General Confederation of Labor), the major Italian labor union. My investigation shows that smaller, local scandals were part of a larger scheme that led to the divestments of relevant sectors of the Italian industry. Sordi also played a key role in many shady businesses – varying from awarding bogus university degrees to toxic waste trafficking. My research unveils an expanded, loose network that highlights the multiple connections between political, economic and criminal forces in the Italian system.