Wilson-Joseph-C.-IV.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INDO 50 0 1106971426 29 60.Pdf (1.608Mb)

A m e r ic a n " L o w P o s t u r e " P o l ic y t o w a r d In d o n e s ia in t h e M o n t h s L e a d in g u p t o t h e 1965 "C o u p " 1 Frederick Bunnell Introduction This article seeks to contribute to the reconstruction, explanation, and evaluation of the Johnson Administration's response to President Sukarno's radicalization of Indonesia's do mestic politics and foreign policy in the first nine months of 1965 leading up to the abortive "coup" on October 1,1965. The focus throughout is on both the thinking and the politics of what can be termed "the 1965 Indonesia policy group."2 That unofficial group was the informal constellation of US officials both in Indonesia (in the Embassy-based country team)3 and in Washington (in the *This article has enjoyed a long, troubled odyssey. Growing out of intermittent research on American-Indonesian relations dating back to my doctoral dissertation field research in Jakarta in 1963-1965, the substance of the article, including its primary conclusions, was presented in papers at the August 1979 Indonesian Studies Con ference in Berkeley and the March 1980 International Studies Association Conference in Los Angeles. I am in debted to the American Philosophical Society, the Lyndon Baines Johnson Foundation, and the Vassar College Faculty Research Committee for grants in 1976-1979 which facilitated the brunt of the archival and interview re search undergirding the article. -

United Nations List of Delegations to the Second High-Level United

United Nations A/CONF.235/INF/2 Distr.: General 30 August 2019 Original: English Second High-level United Nations Conference on South-South Cooperation Buenos Aires, 20–22 March 2019 List of delegations to the second High-level United Nations Conference on South-South Cooperation 19-14881 (E) 110919 *1914881* A/CONF.235/INF/2 I. States ALBANIA H.E. Mr. Gent Cakaj, Acting Minister for Europe and Foreign Affairs H.E. Ms. Besiana Kadare, Ambassador, Permanent Representative Mr. Dastid Koreshi, Chief of Staff of the Acting Foreign Minister ALGERIA H.E. Mr. Abdallah Baali, Ambassador Counsellor, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Alternate Head of Delegation H.E. Mr. Benaouda Hamel, Ambassador of Algeria in Argentina, Embassy of Algeria in Argentina Representatives Mr. Nacim Gaouaoui, Deputy Director, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Mr. Zoubir Benarbia, First Secretary, Permanent Mission of Algeria to the United Nations Mr. Mohamed Djalel Eddine Benabdoun, First Secretary, Embassy of Algeria in Argentina ANDORRA Mrs. Gemma Cano Berne, Director for Multilateral Affairs and Cooperation Mrs. Julia Stokes Sada, Desk Officer for International Cooperation for Development ANGOLA H.E. Mr. Manuel Nunes Junior, Minister of State for Social and Economic Development, Angola Representatives H.E. Mr. Domingos Custodio Vieira Lopes, Secretary of State for International Cooperation and Angolan Communities, Angola H.E. Ms. Maria de Jesus dos Reis Ferreira, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary, Permanent Representative, Permanent Mission of Angola to the United Nations ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA H.E. Mr. Walton Alfonso Webson, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary, Permanent Representative, Permanent Mission Representative Mr. Claxton Jessie Curtis Duberry, Third Secretary, Permanent Mission 2/42 19-14881 A/CONF.235/INF/2 ARGENTINA H.E. -

The Country Team and Local Staff Role | Excerpt from Inside a U.S. Embassy

PART II Foreign Service Work and Life: Embassy, Employee, Family By Shawn Dorman THE EMBASSY AND THE COUNTRY TEAM mbassies are located in the capital city of each country with which the United States has official relations, and serve as headquarters for U.S. gov - Eernment representation overseas. U.S. consulates are ancillary government offices in cities other than the capital. American and local employees serving in U.S. embassies and consulates work under the leadership of an ambassador to conduct diplomatic relations with the host country. The Department of State is the lead agency for conducting U.S. diplomacy and the ambassador, appointed by the U.S. president, reports to the Secretary of State. Diplomatic relations among nations, including diplomatic immunity and the inviolability of embassies, follow procedures framed by the 1961 Vienna Convention on the Conduct of Diplomatic Relations and Optional Protocols, ratified by the U.S. in 1969. The foreign affairs agencies that make up the Foreign Service—the Department of State, the U.S. Agency for International Development, the Foreign Commercial Service, the Foreign Agricultural Service, and the International Broadcasting Bureau—are part of the overall U.S. mission in a country and usually have their offices inside the embassy. Each embassy can also be home to the offices of other U.S. government agencies and departments, in some countries as many as 40 dif - ferent entities. Agencies with a significant overseas presence include the Department of Defense, the Central Intelligence Agency, the Drug Enforcement Agency, the Treasury Department, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the Department of Homeland Security. -

The Foreign Service Journal, April 2014

PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE ASSOCIATION APRIL 2014 GREENING EMBASSIES CHIEf-Of-MISSION GUIDELINES HOW H.A. GILES LEARNED CHINESE FOREIGN April 2014 SERVICE Volume 91, No. 4 AFSA NEWS FOCUS GREENING EMBASSIES AFSA Releases Chief-of-Mission Guidelines / 45 Eco-Diplomacy: Building the Foundation / 20 VP Voice State: Collaborating with Our Partner Organizations / 46 U.S. embassies and consulates around the world are becoming showcases VP Voice Retiree: Retirement for American leadership in best practices and sustainable technology. Begins Before Retirement / 47 BY DONNA M. MCINTIRE VP Voice FCS: The Budget Resource Merry-Go-Round / 48 The Greening Diplomacy Initiative: Chief-of-Mission Guidelines / 49 Capturing Innovation / 24 AFSA Hosts Chiefs of Mission / 51 AFSA On the Hill: State’s homegrown Greening Diplomacy Initiative relies on seeding, Beyond Advocacy Day / 52 harvesting, sifting, implementing and sharing employees’ innovations New Association Management and ideas, large and small. System for AFSA / 53 BY CAROLINE D’ANGELO AFSA VP Meets with Florida Retirees / 54 The League of Green Embassies: 2013 Sinclaire Award Recipients / 54 AFSA Book Notes: American Leadership in Sustainability / 30 America’s First Globals / 55 A coalition of more than 100 U.S. embassies and consulates worldwide AFSA Partners with United Nations shares ideas and practical experience in the field. Association / 56 BY JOHN DAVID MOLESKY FSJ Editor-in-Chief Steps Down / 56 AFSA and DACOR Salute U.S. Marine Security Guards / 57 Finns Take the LEED in Green Embassy Design / 35 The Foreign Service Family: The Finnish embassy in Washington, D.C., is a green building that The Packout and Me / 59 was ahead of its time. -

Table of Contents

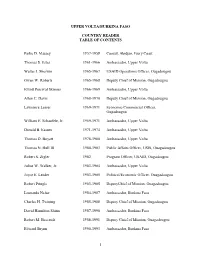

UPPER VOLTA/BURKINA FASO COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Parke D. Massey 1957-1958 Consul, Abidjan, Ivory Coast Thomas S. Estes 1961-1966 Ambassador, Upper Volta Walter J. Sherwin 1965-1967 USAID Operations Officer, Ougadougou Owen W. Roberts 1965-1968 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ougadougou Elliott Percival Skinner 1966-1969 Ambassador, Upper Volta Allen C. Davis 1968-1970 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ougadougou Lawrence Lesser 1969-1971 Economic/Commercial Officer, Ougadougou William E. Schaufele, Jr. 1969-1971 Ambassador, Upper Volta Donald B. Easum 1971-1974 Ambassador, Upper Volta Thomas D. Boyatt 1978-1980 Ambassador, Upper Volta Thomas N. Hull III 1980-1983 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Ouagadougou Robert S. Zigler 1982 Program Officer, USAID, Ougadougou Julius W. Walker, Jr. 1983-1984 Ambassador, Upper Volta Joyce E. Leader 1983-1985 Political/Economic Officer, Ouagadougou Robert Pringle 1983-1985 DeputyChief of Mission, Ouagadougou Leonardo Neher 1984-1987 Ambassador, Burkina Faso Charles H. Twining 1985-1988 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ougadougou David Hamilton Shinn 1987-1990 Ambassador, Burkina Faso Robert M. Beecrodt 1988-1991 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ouagadougou Edward Brynn 1990-1993 Ambassador, Burkina Faso 1 PARKE D. MASSEY Consul Abidjan, Ivory Coast (1957-1958) Parke D. Massey was born in New York in 1920. He graduated from Haverford College with a B.A. and Harvard University with an M.P.A. He also served in the U.S. Army from 1942 to 1946 overseas. After entering the Foreign Service in 1947, Mr. Massey was posted in Mexico City, Genoa, Abidjan, and Germany. While in USAID, he was posted in Nicaragua, Panama, Bolivia, Chile, Haiti, and Uruguay. -

MENA-OECD Ministerial Conference Key Participants & Speakers

Republic of Tunisia MENA-OECD Ministerial Conference Key Participants & Speakers – Biographies Hosts Mr. Beji Caïd Essebsi - President of the Republic - Tunisia Mr. Essebsi is the President of Tunisia since 2014. Previously, Mr. Essebsi held the position of Prime Minister for a brief period – March to October 2011. During his career, the President has held various high level positions, including Head of the Administration of National Security (1963), Minister of Interior from (1965-1969), Minister of Foreign Affairs (1981-1986) and President of the Chamber of Deputies (1990-1991). The President was also ambassador of Tunisia to West Germany and France. Mr. Youssef Chahed - Prime Minister - Tunisia Mr. Chahed was appointed Tunisian Prime Minister in August 2016. Before taking office, Mr. Chahed was Minister of Local Affairs in the previous government and previously held the position of Secretary of State for Fisheries. The Prime Minister is also an international expert in agriculture and agricultural policies for the United States Department of Agriculture, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the European Commission. Mr. Angel Gurría - Secretary-General - OECD Mr. Gurría is the OECD Secretary-General since 2006. The Secretary-General has held two ministerial posts in Mexico before joining the OECD - Minister of Foreign Affairs (1994-1998) and Minister of Finance and Public Credit (1998- 2000). Mr. Gurría chaired the International Task Force on Financing Water for All and is a member of several international initiatives, including the United Nations Secretary General Advisory Board, World Economic Forum’s Global Agenda Council on Water Security, International Advisory Board of Governors of the Centre for International Governance Innovation, among others. -

1 the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project STANLEY JAKUBOWSKI Interviewed by: Mark Tauber Initial interview date: October 2, 2017 Copyright 2019 ADST Q: This is our first recording session with Stan Jakubowski and we always begin with the question of when and where you were born. JAKUBOWSKI: I was born in Jamaica Hospital in Jamaica, New York, Queens County on the seventh of November, 1942 and after initially living in Jamaica for a few years lived in a place in Queens called Ozone Park. It's a small area in New York and at that time, back in the forties and the fifties, I always thought of New York, or I learned to think of New York, as a place of small communities, Ozone Park was a Polish area. All my neighbors, all my friends, my church, were mostly Polish in origin. I was raised a Roman Catholic. At the Catholic Church, Saint Stanislaus, the masses were in Polish. I initially attended a Polish Catholic school where, among other subjects, the nuns tried to teach me Polish. I was not going to learn Polish. If you know some Polish people, they can be stubborn and I don't care what the nuns did to me, I was not going to learn Polish. I was there in that school for roughly four years before my parents moved out to Long Island, part of that great migration after World War Two out to Nassau County. To sort of finish this initial story, I learned later on that all of my grandparents had been born in Poland. -

Protocol for the Modern Diplomat, and Make a Point of Adopting and Practicing This Art and Craft During Your Overseas Assignment

Mission Statement “The Foreign Service Institute develops the men and women our nation requires to fulfill our leadership role in world affairs and to defend U.S. interests.” About FSI Established in 1947, the Foreign Service Institute is the United States Government’s primary training institution for employees of the U.S. foreign affairs community, preparing American diplomats and other professionals to advance U.S. foreign affairs interests overseas and in Washington. FSI provides more than 600 courses – to include training in some 70 foreign languages, as well as in leadership, management, professional tradecraft, area studies, and applied information technology skills – to some 100,000 students a year, drawn from the Department of State and more than 40 other government agencies and military service branches. FSI provides support to all U.S. Government employees involved in foreign affairs, from State Department entry-level specialists and generalists to newly-assigned Ambassadors, and to our Foreign Service National colleagues who assist U.S. efforts at some 270 posts abroad. i Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Protocol In Brief ............................................................................................................................. 2 International Culture ....................................................................................................................... 2 Addressing -

The Foreign Service Journal, November 2016

PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE ASSOCIATION NOVEMBER 2016 FULBRIGHT AND THE FOREIGN SERVICE TURKEYS AT THE BORDER FOREIGN SERVICE November 2016 Volume 93, No. 9 20 Cover Story 20 Fulbright Program at 70: The Foreign Service Connection Members of the Foreign Service, some of them Fulbright alumni, play a crucial role in the continuing success of this singular U.S. exchange program. By Jerome Sherman and James Lawrence Focus on Foreign Service Authors 28 In Their Own Write We are pleased to present this year’s roundup of books by Foreign Service members and their families. By Susan B. Maitra 40 Of Related Interest Here is a short list of other 2016 28 titles of interest to diplomats. THE FOREIGN SERVICE JOURNAL | NOVEMBER 2016 5 FOREIGN SERVICE Departments 10 Letters Perspectives 13 Talking Points 7 78 63 In Memory President’s Views Local Lens 70 Books Championing American Diplomacy Chennai, India By Barbara Stephenson By Ed Malcik 9 Letter from the Editor Sharing Your Stories By Shawn Dorman 17 15 Speaking Out Getting Beyond Bureaucratese— Why Writing Like Robots Damages Marketplace U.S. Interests By Paul Poletes 71 Classifieds 77 74 Real Estate Reflections Turkeys Parade at the Border 76 Index to Advertisers By Victoria Hess 78 AFSA NEWS THE OFFICIAL RECORD OF THE AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE ASSOCIATION 54 Notes from LM: What Not to Say at the Office Holiday Party 55 Agreement Reached on 2013 MSI Remedies 56 Call for AFSA Award Nominations 56 Sinclaire Language Award Nominations 57 FAM Updates: Resources for New Parents 57 Forum Discusses the Carter Administration’s PD Policy 58 Apply Now for AFSA College Scholarships 59 Combined Federal Campaign: A Great Way to 51 Support AFSA 60 Governing Board Meeting Minutes 51 Washington Nationals Honor the U.S. -

Diplomatic List – Fall 2018

United States Department of State Diplomatic List Fall 2018 Preface This publication contains the names of the members of the diplomatic staffs of all bilateral missions and delegations (herein after “missions”) and their spouses. Members of the diplomatic staff are the members of the staff of the mission having diplomatic rank. These persons, with the exception of those identified by asterisks, enjoy full immunity under provisions of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations. Pertinent provisions of the Convention include the following: Article 29 The person of a diplomatic agent shall be inviolable. He shall not be liable to any form of arrest or detention. The receiving State shall treat him with due respect and shall take all appropriate steps to prevent any attack on his person, freedom, or dignity. Article 31 A diplomatic agent shall enjoy immunity from the criminal jurisdiction of the receiving State. He shall also enjoy immunity from its civil and administrative jurisdiction, except in the case of: (a) a real action relating to private immovable property situated in the territory of the receiving State, unless he holds it on behalf of the sending State for the purposes of the mission; (b) an action relating to succession in which the diplomatic agent is involved as an executor, administrator, heir or legatee as a private person and not on behalf of the sending State; (c) an action relating to any professional or commercial activity exercised by the diplomatic agent in the receiving State outside of his official functions. -- A diplomatic agent’s family members are entitled to the same immunities unless they are United States Nationals. -

The Foreign Service Journal, November 2016.Pdf

PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE ASSOCIATION NOVEMBER 2016 FULBRIGHT AND THE FOREIGN SERVICE TURKEYS AT THE BORDER FOREIGN SERVICE November 2016 Volume 93, No. 9 20 Cover Story 20 Fulbright Program at 70: The Foreign Service Connection Members of the Foreign Service, some of them Fulbright alumni, play a crucial role in the continuing success of this singular U.S. exchange program. By Jerome Sherman and James Lawrence Focus on Foreign Service Authors 28 In Their Own Write We are pleased to present this year’s roundup of books by Foreign Service members and their families. By Susan B. Maitra 40 Of Related Interest Here is a short list of other 2016 28 titles of interest to diplomats. THE FOREIGN SERVICE JOURNAL | NOVEMBER 2016 5 FOREIGN SERVICE Departments 10 Letters Perspectives 13 Talking Points 7 78 63 In Memory President’s Views Local Lens 70 Books Championing American Diplomacy Chennai, India By Barbara Stephenson By Ed Malcik 9 Letter from the Editor Sharing Your Stories By Shawn Dorman 17 15 Speaking Out Getting Beyond Bureaucratese— Why Writing Like Robots Damages Marketplace U.S. Interests By Paul Poletes 71 Classifieds 77 74 Real Estate Reflections Turkeys Parade at the Border 76 Index to Advertisers By Victoria Hess 78 AFSA NEWS THE OFFICIAL RECORD OF THE AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE ASSOCIATION 54 Notes from LM: What Not to Say at the Office Holiday Party 55 Agreement Reached on 2013 MSI Remedies 56 Call for AFSA Award Nominations 56 Sinclaire Language Award Nominations 57 FAM Updates: Resources for New Parents 57 Forum Discusses the Carter Administration’s PD Policy 58 Apply Now for AFSA College Scholarships 59 Combined Federal Campaign: A Great Way to 51 Support AFSA 60 Governing Board Meeting Minutes 51 Washington Nationals Honor the U.S. -

Do Not Misinterpret Words of Al-Quran Is Published Monthly by the Department of Information

Published by the Department of Information MAY/JUNE, 2008 Prime Minister’s Office VOLUME 23 ISSUE 5/6 BERAKAS, May 29 – Claims saying that the teaching of the Al- Do not misinterpret Quran is encouraging to threat the security of others and cause chaos to world peace are deeply disappointing. This was said by His Majesty Sultan Haji Hassanal Bolkiah words of Al-Quran Mu’izzaddin Waddaulah, The Sultan and Yang Di-Pertuan of Brunei Darussalam at the final of the Al-Quran National Reading Competition for Adults held at the International Convention Centre. His Majesty was referring to a short film documentary that was disseminated through websites and has caused widespread controversy. Those responsible were trying to infuse doubts on people’s mind about the Al-Quran by saying that it encouraged war and killings. Some individuals tried to misinterpret the teachings by taking shorts verses of the chapters. The part of the verses they picked was not complete and ignored the rest of sentences by not including them in its entirety. His Majesty further said that the verse should read in its entirety to understand the full meaning. The sovereign also presented prizes to winners of the competition. Awangku Muhammad Adibulamin bin Pengiran Haji Marjuki and Dayang Nurfaezah binti Haji Emran emerged as PHOTO: AMPUAN HAJI MAHMUD TENGAH champions of this year’s Al-Quran National Reading Competition His Majesty presents a prize to Ak. Mohd. Adibulamin, for Adults 1429/2008. champion of the National Al-Quran Reading Competition Also present at this ceremony were His Royal Highness Prince for Adults 1429H/2008 Haji Sufri Bolkiah and His Royal Highness Prince ‘Abdul Mateen.