American University of Prague

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An “Archetypal Memory” Advantage?

Behav.Sci.2013, 3, 541–561; doi:10.3390/bs3040541 OPEN ACCESS behavioral sciences ISSN 2076-328X www.mdpi.com/journal/behavsci Article Symbol/Meaning Paired-Associate Recall: An “Archetypal Memory” Advantage? Milena Sotirova-Kohli 1,*, Klaus Opwis 1, Christian Roesler 1, Steven M. Smith 2, David H. Rosen 3, Jyotsna Vaid 2 and Valentin Djonov 4 1 Department of Psychology, University of Basel, Missionstrasse60/62, Basel 4055, Switzerland; E-Mails: [email protected] (K.O.); [email protected] (C.R.) 2 Department of Psychology, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (S.M.S.); [email protected] (J.V.) 3 School of Medicine, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR 97239, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 4 Institute of Anatomy, University of Bern, Balzerstrasse 2, Bern 3000, Switzerland; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]. Received: 29 August 2013; in revised form: 25 September 2013 / Accepted: 27 September 2013 / Published: 9 October 2013 Abstract: The theory of the archetypes and the hypothesis of the collective unconscious are two of the central characteristics of analytical psychology. These provoke, however, varying reactions among academic psychologists. Empirical studies which test these hypotheses are rare. Rosen, Smith, Huston and Gonzales proposed a cognitive psychological experimental paradigm to investigate the nature of archetypes and the collective unconscious as archetypal (evolutionary) memory. In this article we report the results of a cross-cultural replication of Rosen et al. conducted in the German-speaking part of Switzerland. -

The Collective Unconscious in Eugene O`Neill`S Desire Under The

Aleppo University Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of English The Collective Unconscious in Eugene O`Neill`s Desire Under the Elms and Mourning Becomes Electra and George Bernard Shaw`s Pygmalion and Man and Superman: A Comparative Study By Diana Dasouki Supervised by Prof. Dr. Iman Lababidi A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts In English Literature 2018 i Dasouki Declaration I hereby certify that this work, "The Collective Unconscious in Eugene O`Neill`s Desire Under the Elms and Mourning Becomes Electra and George Bernard Shaw`s Pygmalion and Man and Superman: A Comparative Study", has neither been accepted for any degree, nor is it submitted to any other degrees. Date: / / 2018 Candidate Diana Dasouki ii Dasouki Testimony I testify that the described work in this dissertation is the result of a scientific research conducted by the candidate Diana Dasouki under the supervision of Prof. Dr. Iman Lababidi, professor doctor at the Department of English, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Aleppo University. Any other references mentioned in this work are documented in the text of this dissertation. Date: / / 2018 Candidate Diana Dasouki iii Dasouki Abstract This dissertation explores the theory of the collective unconscious in Eugene O'Neill's Desire Under the Elms and Mourning Becomes Electra and George Bernard Shaw's Pygmalion and Man and Superman. The main objective is to study how the work of Jung has awakened interest in the unconscious and archetype psychology. The collective unconscious is a useful theory because studying literature, myth and religion through archetypes can reveal many deep and hidden meanings. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/30/2021 07:16:13AM Via Free Access 200 J

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF JUNGIAN STUDIES 2018, VOL. 10, NO. 3, 199–220 https://doi.org/10.1080/19409052.2018.1503808 The Essence of Archetypes Jon Mills Department of Psychology, Adler Graduate Professional School, Toronto, Canada ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Jung’s notion of the archetype remains an equivocal concept, so Archetypes; analytical much so that Jungians and post-Jungians have failed to agree on psychology; collective its essential nature. In this essay, I wish to argue that an archetype unconscious; archaic may be understood as an unconscious schema that is self- ontology; origins of mind; unconscious schemata; constitutive and emerges into consciousness from its own a priori metaphysics of difference; ground, hence an autonomous self-determinative act derived dialectics from archaic ontology. After offering an analysis of the archetype debate, I set out to philosophically investigate the essence of an archetype by examining its origins and dialectical reflections as a process system arising from its own autochthonous parameters. I offer a descriptive explication of the inner constitution and birth of an archetype based on internal rupture and the desire to project its universality, form, and patternings into psychic reality as self-instantiating replicators. Archetypal content is the appearance of essence as the products of self-manifestation, for an archetype must appear in order to be made actual. Here we must seriously question that, in the beginning, if an archetype is self-constituted and self-generative, the notion and validity of a collective unconscious becomes rather dubious, if not superfluous. I conclude by sketching out an archetypal theory of alterity based on dialectical logic. -

Contemporary Indigenous Women's Fiction from the Pacific: Discourses of Resistance and the (Re)Writing of Spaces of Violence and Desire

DOCTORAL DISSERTATION Contemporary Indigenous Women's Fiction from the Pacific: Discourses of Resistance and the (Re)Writing of Spaces of Violence and Desire Ana Cristina Gomes da Rocha 2021 International Mention Ana Cristina Gomes da Rocha DOCTORAL DISSERTATION Contemporary Indigenous Women's Fiction from the Pacific: Discourses of Resistance and the (Re)Writing of Spaces of Violence and Desire Supervised by Dr. Belén Martín Lucas 2021 International Mention International Doctoral School Belén Martín Lucas DECLARES that the present work, entitled “Contemporary Indigenous Women's Fiction from the Pacific: Discourses of Resistance and the (Re)Writing of Spaces of Violence and Desire”, submitted by Ana Cristina Gomes da Rocha to obtain the title of Doctor, was carried out under her supervision in the PhD programme “Interuniversity Doctoral Programme in Advanced English Studies.” This is a joint PhD programme integrating the Universities of Santiago de Compostela (USC), A Coruña (UDC), and Vigo (UVigo). Vigo, January 21, 2020. The supervisor, Dr. Belén Martín Lucas Acknowledgments Gratitude. I am grateful. Those are the expressions that best describe my state of mind when looking at this Dissertation. I am grateful that I have been always surrounded by those who never cease(d) to believe in me, by people whose love and support made this journey easier. I would like to say thanks: To my supervisor, Dr. Belén Martín Lucas, whose kindness, wise advice, patience, and unconditional belief in me, and in this project were fundamental along the process. Thank you for holding my hand until I finally believed that I could do this. Thank you for finding meaning in my tangential ideas. -

Expressionism and the Psychoanalysis of Freud and Jung in Anna Christie

(00065 ) Expressionism and the Psychoanalysis of Freud and Jung in Anna Christie Kumi Ohno I. Introduction I have explained the core of expressionism seen in Emperor Jones and Hairy Ape in my previous thesis, Expressionism in O’Neill’s Works.1) I also pointed out the deep influence of the German expressionism led by Strindberg, frequently used in the plays of O’Neill. The fundamental nature of German expressionism can be characterized by its dynamism and vision with its black humor expressed in obsession. O’Neill also expressed the emotional sensations rooted deep in the minds of the characters through his detailed portrayals of the characters’ personali- ties in the form of emotional outbursts that revealed their hidden human nature, the cry of the human soul. O’Neill’s revolutionary and innovative techniques in the play appear in the form of his script writing—where he gives the characters short, choppy phrases like telegrams—and the stage settings and designs, broad and audacious direction of the play and effective use of crowds, lighting and other stage effects. In Anna Christie, O’Neill applies German expressionism in vari- ous forms to show the underlying human psychology of the characters while adopting “social expressionism”2) in its original context. This method is referred to as “Psychological Expressionism”3) and represents German expressionism of inner human emotions. At the same time, 1) Expressionism in O’Neill’s Works, Studies in English Language and Literature No. 31 (Vol. 17, No.1) Soka University, December, 1992, pp.129–145 2) John Willet, Expressionism (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1970), World University Library, p. -

The Dialogical Jung: Otherness Within the Self

Behav. Sci. 2013, 3, 634-646; doi:10.3390/bs3040634 OPEN ACCESS behavioral sciences ISSN 2076-328X www.mdpi.com/journal/behavsci/ Article The Dialogical Jung: Otherness within the Self William E. Smythe Psychology Department, University of Regina, 3737 Wascana Parkway, Regina S4S 0A2, SK, Canada; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +306-585-4219; Fax: +306-585-4772 Received: 25 September 2013; in revised form: 13 November 2013 / Accepted: 15 November 2013 / Published: 21 November 2013 Abstract: This paper explores dialogical currents in Jung’s analytical psychology, with reference to contemporary theories of the dialogical self. The dialogical self is a notion that has gained increasing currency in psychology since the 1990s, in response to the limitations of traditional notions of the self, based on monological, encapsulated consciousness. Modern dialogical self theory construes the self as irrevocably embedded in a matrix of real and imagined dialogues with others. The theme of dialogical otherness within the self is also taken up in Jung’s analytical psychology, both in the practice of active imagination and psychotherapy and in the theory of archetypes, and a dialogical approach to inquiry is evident in Jung’s work from the outset. The implications of a dialogical re-conceptualization of analytical psychology and of analytical psychology for dialogical theory are considered in detail. Keywords: analytical psychology; dialogical self; archetypes; otherness 1. Introduction In a recent essay Charles Taylor identified the problem of understanding the other as “the great challenge of this century both for politics and social science” ([1], p.24). What analytical psychology can uniquely contribute with respect to this challenge is to give an account of the other within the self. -

C. G. Jung's Theory of the Collective Unconscious

C.G. JinTG'S THEORY OF THE C0LLECTI7E UNCONSCIOUS: A RATIONAL RECONSTRUCTION TMLTER A70RY SHELBURNE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVTKSITr OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFTLU^IENT OF THE REQUIREMEI'ITS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHUOSOPHT UNITERSITZ OF FLORIDA 1976 UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 3 1262 08666 238 3 Copyright 1976 Vfelter Avoiy Shelbume ACKMOIilLEDOENTS I irould like to grateful^sr acloioirledge the persons of rcr supervisory committee for their help in this project: Marilyn areig, Tom Aarber, i^anz lifting, Richard Ilaynes and Tom Simon. Special thanks to Iferiljoi and Tom Sijnon for their tiine, encouragement and helpful criticism. I would also like to thank Debbie Botjers of the Graduate School, who, in addition to her technical advice, has through her friendliness contri- buted in an immeasurable and intangible way to the final preparation of this manuscript, 3h addition to this personal assistance, I TTould also like to aclaiow- ledge the help of the follo;.jing agencies: the spirit of Carl Gustav Jung, the Archetn>e of the Self, and the three luminous beings tAo cleansed iry spirit. iii , TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACiaro V/LEDGlJEI'rPS iii ABSTRACT , ^ HrPRODUCTION ,, ., CHAPTER 1 JUl'JG'S I-IEMTAL CONSTRUCTS.. ,,.., 3 Pgyxjhe...... , ,,, 3 Uiconscioiis. .,, .,,, 16 Collective Ifciconscious. , 19 Notes. .................,,..,,,,,,,,, , 28 CHAPTER 2 TI£EORr OF ARCHETTPES: PART I ,,,, 30 Introduction,.., , ,,.,,. ..,,,. 30 The Syrabolic Mature of the Archetypes ,, , l^;^ Archetiypes and Instincts ,,,,... hi Notes.... , ..,,,.. , ,, ^3 CHAPTER 3 THEOrar OF ARCHETn=ES: PART II..... ^ The Origin of the Archetypes ^ Archelypal ninage and Archetype Per Se ., 63 Tlae .'irchetypes as Autonomous Factors,. -

Abstracts 2021

IAJS/ Duquesne University Conference, March 18-21, 2021 Authors and Abstracts Apocalypse Imminent: A depth psychological analysis of human responses to fear of catastrophe and extinction. J. Alvin and E. Hanley In the dire situation of the world today, humans are striving to cope with impending catastrophes and end of life on Earth. Emergency food buckets with a shelf life of 25 years are now sold in quantities that provide a year of lasting sustenance for an individual. Efforts to colonize Mars are underway and its pop-culture representations are based on key narratives of American heritage: ingenuity/technology, the great frontier/utopia, and democracy/capitalism. The configuration of apocalyptic social phenomena, arranged in a cultural and astrological gestalt, may be reminiscent of other points in human history where the threat of catastrophe rendered similar archetypal expression. As psychologists, we must ask: what precisely is being achieved by the development and sale of stockpiled food and plans to colonize other planets? What are we turning toward and away from? What kind of life are we buying into? Key concepts explored in the research of these topics include technology, climate change, food sustainability, cultural complex, and more. To be explored in a discussion panel are the archetypal root and metaphor of these social phenomena and the implications these endeavors have for humanity entering the next phase of existence. It is our intention to present papers on the above topics and, with Dr. Romanyshyn as a respondent, facilitate an in-depth and meaningful discussion. 1 Wise emergency survival food storage Jonathan Alvin The purpose of this philosophical hermeneutic study will be to understand the Wise Emergency Survival Food Storage (WESFS) as an artifact that reflects and reproduces its cultural matrix (Cushman, 1996). -

The Pennsylvania State University

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Department of Comparative Literature ARCHETYPES AND AVATARS: A CASE STUDY OF THE CULTURAL VARIABLES OF MODERN JUDAIC DISCOURSE THROUGH THE SELECTED LITERARY WORKS OF A. B. YEHOSHUA, CHAIM POTOK, AND CHOCHANA BOUKHOBZA A Dissertation in Comparative Literature by Nathan P. Devir © 2010 Nathan P. Devir Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2010 The dissertation of Nathan P. Devir was reviewed and approved* by the following: Thomas O. Beebee Distinguished Professor of Comparative Literature and German Dissertation Advisor Co-Chair of Committee Daniel Walden Professor Emeritus of American Studies, English, and Comparative Literature Co-Chair of Committee Baruch Halpern Chaiken Family Chair in Jewish Studies; Professor of Ancient History, Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies, and Religious Studies Kathryn Hume Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of English Gila Safran Naveh Professor of Judaic Studies and Comparative Literature, University of Cincinnati Special Member Caroline D. Eckhardt Head, Department of Comparative Literature; Director, School of Languages and Literatures *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. iii ABSTRACT A defining characteristic of secular Jewish literatures since the Haskalah, or the movement toward “Jewish Enlightenment” that began around the end of the eighteenth century, is the reliance upon the archetypal aspects of the Judaic tradition, together with a propensity for intertextual pastiche and dialogue with the sacred texts. Indeed, from the revival of the Hebrew language at the end of the nineteenth century and all throughout the defining events of the last one hundred years, the trend of the textually sacrosanct appearing as a persistent motif in Judaic cultural production has only increased. -

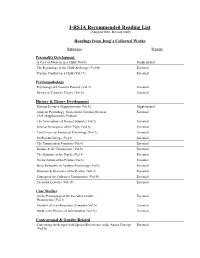

I-RSJA Recommended Reading List (Adopted 2001, Revised 2009)

I-RSJA Recommended Reading List (Adopted 2001, Revised 2009) Readings from Jung’s Collected Works Reference Priority Personality Development A Case of Neurosis in a Child (Vol 4) Supplemental The Psychology of the Child Archetype (Vol 9i) Essential Psychic Conflicts in a Child (Vol 17) Essential Psychopathology Psychology of Dementia Praecox (Vol 3) Essential Review of Complex Theory (Vol 8) Essential History & Theory Development Zofinga Lectures (Supplementary Vol A) Supplemental Analytic Psychology: Notes on the Seminar Given in Essential 1925 (Supplementary Volume) The Associations of Normal Subjects (Vol 2) Essential General Description of the Types (Vol 6) Essential Two Essays on Analytical Psychology (Vol 7) Essential On Psychic Energy (Vol 8) Essential The Transcendent Function (Vol 8) Essential Instinct & the Unconscious (Vol 8) Essential The Structure of the Psyche (Vol 8) Essential On the Nature of the Psyche (Vol 8) Essential Basic Postulates of Analytic Psychology (Vol 8) Essential Structure & Dynamics of the Psyche, (Vol 8) Essential Concept of the Collective Unconscious (Vol 9i) Essential Tavistock Lectures (Vol 18) Essential Case Studies On the Psychology of the So-called Occult Essential Phenomenon (Vol 1) Symbols of Transformation (Complete Vol 5) Essential Study in the Process of Individuation (Vol 9i) Essential Contrasexual & Gender-Related Concerning Archetypes with Special Refererence to the Anima Concept Essential (Vol 9i) Page - 2 Development of the Analyst & the Development of Analytic Practice The Practice of -

The Birth of a Nation

The Birth of a Nation by Christian Lanciai (1986, translated 2017) Dramatis personae: Godrith Saxwolf, messenger Mallet de Graville, Norman Harold Godwinson, Earl of England Edith, his cousin and beloved Earl Godwin, his father Edward the Confessor, King of England Edith, his Queen, Harold’s sister Aldyth, daughter of King Elgar of Wales Torstig, Gurth and Haco, Harold’s brothers William, Duke of Normandy Mathilda, his wife Bishop Udo of Bayeux, William’s brother Alred, Bishop of York Stigand, Abbot of Westminster Harold Hardrade, King of Norway Hugues Maigrot, Norman monk and diplomat A servant An old Saxon chief Other leading Saxons A Norman priest A doctor Norman barons and counsellors A Norwegian squire Norwegian warrior An English courier English soldiers Norman soldiers Anglo-Saxon priests The scene is England and France up until 1066. Act I scene 1. A forest in England. Godrith Halt, if you are a man! Mallet de Graville Halt yourself, whoever you are! Godrith Friend or foe? Graville Foe to anyone who doesn’t befriend me. Godrith You speak like a Norman. Graville And you speak like a true Saxon blackguard. Godrith What are you doing in England? Graville I am on a mission by Duke William of Normandy. Godrith What does he want of England? Graville He desires the throne after your King Edward the Confessor, who is old and frail as the last of his family. Godrith Would a Frenchman make himself King of England? Graville My good man, everyone knows, and you as well, that William of Normandy is the King’s closest of kin, being married to Mathilda, a relative of Alfred the Great. -

2014–2015 Course Catalog Masters and Doctoral Programs in the Tradition of Depth Psychology

PACIFICA GRADUATE INSTITUTE 2014–2015 Course Catalog Masters and Doctoral Programs in the Tradition of Depth Psychology Table of Contents M.A./Ph.D. in Mythological Studies ........................................................... 3 M.A./Ph.D. in Depth Psychology .............................................................. 17 Emphasis in Jungian and Archetypal Studies ..................................... 19 Emphasis in Community Psychology, Liberation Psychology, and Ecopsychology ................................................................................... 31 Emphasis in Somatic Studies .............................................................. 47 Ph.D. in Depth Psychology with Emphasis in Psychotherapy ............. 63 M.A. in Engaged Humanities and the Creative Life ............................... 79 M.A. in Counseling Psychology ............................................................... 90 Doctoral Programs in Clinical Psychology ........................................... 114 Psy.D. in Clinical Psychology with Emphasis in Depth Psychology .. 116 Ph.D.. in Clinical Psychology with Emphasis in Depth Psychology .. 140 _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Administration and Staff ........................................................................ 162 Faculty ...................................................................................................... 164 Admissions Requirements and Procedures ........................................