Saudi Arabia After Oil Final Report – Group 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rail Opportunities 5 – 6 May 2014 Riyadh Intercontinental, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

SUPPORTED BY ORGANISED BY VISIT OUR WEBSITE: www.fleminggulf.com Expanding Trade Tracks : Boosting Economy in a Dynamic Region 5th Annual Middle East Rail Opportunities 5 – 6 May 2014 Riyadh InterContinental, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Speakers & Panelists KEY PROJECTS SAPTCO Metro Eng. Ibrahim K. Khalid Al Hogail François-Xavier Perin, Dr. Shahid Khan & Light Rail Kutubkhanah Saudi Public Transport Régie Autonome des Saudi Binladin Group Metro Jeddah Company, Company (SAPTCO), Transports Parisiens Project Director, Saudi Arabia Project Chief Executive Officer, Chief Executive Officer, Development (RATP Dev) Saudi Arabia Saudi Arabia Chief Executive Officer, France Jeddah Metro Project Luis Sánchez Monserrat Rabii Ouadi, Huawei Dr. Gaffar Imtiaz Xu Zongxiang, CSR Administrador de Technologies, Head of Jeddah Municipality Vice President, China Business Development, Infraestructuras Senior Advisor to CEO, Saudi Transportation Vertical Ferroviarias (ADIF), Market, Middle East and Arabia Director, Saudi Arabia North Africa, China North South Railway Link Loay Ghazaleh, Ministry H.E. Dr. Nadhem Bin Eng Tariq Abdulrahman Cesare Brand, CIT – Rail, of Works, Bahrain, PPP Taher, National Transport Al Marzouki, Council of Secretary General, Theme Leader & Advisor to the Authority (NTA), Executive Saudi Chambers, Switzerland Undersecretary of Works, Director, Service Provision Center Chairman of Transport Haramain High Bahrain Sector, UAE Committee, Saudi Arabia Speed Rail Project H.E. Laith H. François Davenne, John Sfakianakis, Senior Representative, -

Railways of the MENA Region, Tools of National and Foreign Policy

DHEEI – Mediterranean Studies Railways of the MENA Region, tools of national and foreign policy Master’s Thesis submitted by GALLOY Théophile Academic year: 2018-2019 Thesis Supervisor: Dr. Silvia Colombo Acknowledgements I wish to express my appreciation to my family, my co-students and CIFE for their valuable support throughout this year. I am also very grateful for the advice given by my fantastic supervisor Dr. Silvia Colombo, who has kindly dedicated some time to read, correct and advise me on my work, whilst allowing me to remain creative in my approach and research. I would also like to extend my thanks to my previous manager, Mr. Stephane Downes, and my previous employer, Mr. Stephane Rambaud-Measson, for opening me the doors of the railway industry and for passing on to me their knowledge and passion for this fascinating sector. I would also like to thank Dr. Ayadi Soufiane, the surgeon who successfully removed my infected appendix in Tunis, which allowed me to continue my work unimpeded. 2 Acknowledgements_____________________________________________________2 Table of Contents_______________________________________________________3 Introduction___________________________________________________________4 Part I: Understanding the political benefits of railway infrastructures______________6 1) The economic and social benefits of rail_____________________________6 2) Rail as a nation building infrastructure, a tool of power________________12 3) Rail as a region building infrastructure, a tool of integration____________19 Part II: -

Saudi Arabia: Transport & Logistics July 2016 Saudi Arabia: Transport & Logistics

Saudi Arabia: Transport & Logistics July 2016 Saudi Arabia: Transport & Logistics TABLE OF CONTENTS Map of Saudi Arabia ............................................................................................ 4 Executive Summary ............................................................................................. 5 Industry Structure ................................................................................................. 6 Market Overview ................................................................................................... 7 Rail Transport & Logistics ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 Figure: Planned Railway Network .......................................................................................................................................... 8 Public Transport ........................................................................................................................................................................ 9 Maritime Transport & Logistics .......................................................................................................................................... 10 Road Transport & Logistics ................................................................................................................................................... 11 Figure: Road Network by Region ......................................................................................................................................... -

Investigation Future Planning of Railway Networks in the Arabs Gulf Countries

M. E. M. Najar & A. Khalfan Al Rahbi, Int. J. Transp. Dev. Integr., Vol. 1, No. 4 (2017) 654–665 INVESTIGATION FUTURE PLANNING OF RAILWAY NETWORKS IN THE ARABS GULF COUNTRIES MOHAMMAD EMAD MOTIEYAN NAJAR & ALIA KHALFAN AL RAHBI Department of Civil Engineering, Middle East College, Muscat, Oman ABSTRACT Trans-border railroad in the Arabian Peninsula dates back to the early 20th century in Saudi Arabia. Over the recent decades due to increasing population and developing industrial zones, the demands are growing up over time. The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) is now embarking on one of the largest modern cross-border rail networks in the world. This is an ambitious step regarding the planning and establishment of the rail network connecting all the six GCC countries. This railway network will go through at least one city in each country to link the cities of Kuwait in Kuwait, Dammam in Saudi Arabia, Manama in Bahrain, Doha in Qatar, the cities of Abu Dhabi and Al Ain in the United Arab Emirates and Sohar and then Muscat in Oman in terms of cargo and passengers. The area of investigation covers different aspects of the shared Arabian countries rail routes called ‘GCC line’ and their national rail network. The aim of this article is to study the existing future plans and policies of the GCC countries shared line and domestic railway network. This article studies the national urban (light rail transportation (LRT), metro (subways) and intercity rail transportation to appraise the potential of passenger movement and commodity transportation at present and in the future. -

Middle East Rail Projects Report

Middle East Rail Projects Report A must have guide for anyone looking to access the Middle East Rail industry created by Published: May 2013 www.terrapinn.com/merail Contents Investment Overview. .................................................... 2 Executive Summary ....................................................... 3 Saudi Arabia ................................................................... 4 Saudi Railway Company Interview .............................. 7 Qatar ............................................................................... 8 Qatar Rail Interview ....................................................... 10 United Arab Emirates .................................................... 11 Etihad Rail Interview ..................................................... 14 Iran .................................................................................. 16 Oman .............................................................................. 17 Bahrain. .......................................................................... 18 Kuwait. ............................................................................ 19 Top Influencers in Middle East Rail ............................. 20 Building for the future www.terrapinn.com/merail Investment, investment, investment! The Middle East is fast shedding the traditional image of rolling sand dunes and meandering camel rides and replacing it with gleaming golden metro stations and high speed trains powering through the desert. Within the next 10 years we will see a complete -

Egis Press Kit Middle-East | November 2017 1

Egis press kit Middle-East | November 2017 1 CONTENTS 1. EGIS AT A GLANCE Erreur ! Signet non défini. 2. OUR GLOBAL OFFER 3 3. OUR PERFORMANCES IN 2016 4 4. OUR AMBITION 9 5. FOCUS ON MIDDLE-EAST 15 6. AWARDS Erreur ! Signet non défini. 7. MAIN REFERENCES 15 Egis press kit Middle-East | November 2017 2 1. EGIS AT A GLANCE 13,800 employees €1.020 billion of managed turnover in 2016 63% of managed turnover generated outside France 27 road operating subsidiaries around the world A network of 17airports in 8 countries With a focus on designing the long term, Egis is one of the world leaders in construction engineering and regional planning and development. Displaying a unique global offer, the Group combines the know-how of engineering with the skills of project development, capital investment, turnkey facilities operations and services for mobility. Egis is an active player and a trusted partner in the fundamental areas of transport, building, water, the environment and major structures, and also in energy, aviation, urban development and digital engineering. Egis press kit Middle-East | November 2017 3 2. OUR GLOBAL OFFER Egis assists its public and private sector clients in their development projects which link in with the major transitions underway in our society: energy and ecological, digital and technological, demographic and territorial. The Group proposes a global consulting and engineering service offer which contributes tailored and innovative operational and technical responses in a wide range of fields: urban resilience and adaptation of infrastructure to climate change, renovation of constructions and eco-design, transport and mobility, energy strategy (urban heating networks, waste-to-energy, etc.), digital development and urban intelligence. -

Saudi Arabia World Trade Forum

Under the Patronage of Saudi Arabia world trade forum 11-13 NOVEMBER 2018 Riyadh International Convention & Exhibition Center Licensed by Organizers Recexpos Member 920024020 www.recexpo.com Follow us : SAUDI TRANSPORT AND LOGISTIC SERVICES Riyadh International Convention & Center Transport and logistics infrastructure the Kingdom’s multi-billion dollar engine for growth and diversification Transportation has always been an important next 10 years in expanding and upgrading its pillar of every nation’s economy and the key to transportation sector, acknowledging its big need sustainable development. Therefore, it is con- to expand its five main sector’s components: sidered one of the main sectors that contribute maritime, rail, road, air transportation, warehous- effectively to the renaissance of any country. ing and distribution seaports. Major infrastruc- Without an efficient transport sector, it would be ture projects include Riyadh Metro, Mecca Metro, hard to benefit from the basic advantages of any Jeddah Airport and Riyadh Airport. location or invest in the available opportunities for production. Since 2008, the Saudi government have invested heavily in transport infrastructure projects as part of its efforts to expand and diversify the economy. Ports have been built, airports expand- ed and upgraded, and railway and metro projects initiated and in some cases already completed. Saudi Arabia is investing US$140 billion over the Transportation sector and population growth The transportation and logistics sector has played a prominent role in the socio-economic development of Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Given the worldwide trends and statistics on urban population growth, the country has always focused on re-planning and re-designing of existing cities in order to absorb the pressure of increasing urban populations, in a man- ner that will improve environmental sustainability and energy efficiency. -

Infrastructure Sector: Overview and Commercial Prospects in Saudi Arabian and U.S

2017 INDUSTRY SECTOR REPORT Infrastructure Sector: Overview and Commercial Prospects in Saudi Arabian and U.S. Construction, Real Estate, and Transport www.us-sabc.org Disclaimer The information that is published in this report was analyzed and compiled from sources believed to be accurate and reliable during the time of publication. The U.S.-Saudi Arabian Business Council accepts no liability for any loss or damage resulting from errors or omissions due to human or mechanical error in any part of this report. The U.S.-Saudi Arabian Business Council provides all information without any warranty. © 2017 The U.S.-Saudi Arabian Business Council. All rights reserved. Neither this publication nor any part of it may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the U.S.-Saudi Arabian Business Council. Reports are published quarterly by the U.S.-Saudi Arabian Business Council, 8081 Wolftrap Road, Suite 300, Vienna, VA 22182. 2 U.S.-Saudi Arabian Business Council Table of Contents 4 Executive Summary SAUDI ARABIAN MARKET 6 Trends in Contracts 7 Growing Value of Infrastructure 8 Government Infrastructure Goals and Financing 9 Infrastructure Objectives through Vision 2030 and the NTP 10 Government Bodies Involved in the Infrastructure Sector 11 Private Sector Initiatives 12 Oil Revenues and Government Projects 14 Financing 15 Regional Trends in Contracts Awarded 16 Domestic and Foreign Firms Involved in Saudi Arabian Infrastructure 20 Macroeconomic Trends 22 Housing Market 24 Transportation 27 Tourism Construction 29 Building Automation 29 Construction Supply Chain for Raw Materials 31 Labor 33 Real Estate 36 Infrastructure Projects in Energy 39 Industrial Infrastructure Projects 40 Special Projects 41 SME’s 41 Restarting Stalled Projects 42 Construction of Social Facilities 42 Commercial Construction U.S. -

Global Report Global Metro Projects 2020.Qxp

Table of Contents 1.1 Global Metrorail industry 2.2.2 Brazil 2.3.4.2 Changchun Urban Rail Transit 1.1.1 Overview 2.2.2.1 Belo Horizonte Metro 2.3.4.3 Chengdu Metro 1.1.2 Network and Station 2.2.2.2 Brasília Metro 2.3.4.4 Guangzhou Metro Development 2.2.2.3 Cariri Metro 2.3.4.5 Hefei Metro 1.1.3 Ridership 2.2.2.4 Fortaleza Rapid Transit Project 2.3.4.6 Hong Kong Mass Railway Transit 1.1.3 Rolling stock 2.2.2.5 Porto Alegre Metro 2.3.4.7 Jinan Metro 1.1.4 Signalling 2.2.2.6 Recife Metro 2.3.4.8 Nanchang Metro 1.1.5 Power and Tracks 2.2.2.7 Rio de Janeiro Metro 2.3.4.9 Nanjing Metro 1.1.6 Fare systems 2.2.2.8 Salvador Metro 2.3.4.10 Ningbo Rail Transit 1.1.7 Funding and financing 2.2.2.9 São Paulo Metro 2.3.4.11 Shanghai Metro 1.1.8 Project delivery models 2.3.4.12 Shenzhen Metro 1.1.9 Key trends and developments 2.2.3 Chile 2.3.4.13 Suzhou Metro 2.2.3.1 Santiago Metro 2.3.4.14 Ürümqi Metro 1.2 Opportunities and Outlook 2.2.3.2 Valparaiso Metro 2.3.4.15 Wuhan Metro 1.2.1 Growth drivers 1.2.2 Network expansion by 2025 2.2.4 Colombia 2.3.5 India 1.2.3 Network expansion by 2030 2.2.4.1 Barranquilla Metro 2.3.5.1 Agra Metro 1.2.4 Network expansion beyond 2.2.4.2 Bogotá Metro 2.3.5.2 Ahmedabad-Gandhinagar Metro 2030 2.2.4.3 Medellín Metro 2.3.5.3 Bengaluru Metro 1.2.5 Rolling stock procurement and 2.3.5.4 Bhopal Metro refurbishment 2.2.5 Dominican Republic 2.3.5.5 Chennai Metro 1.2.6 Fare system upgrades and 2.2.5.1 Santo Domingo Metro 2.3.5.6 Hyderabad Metro Rail innovation 2.3.5.7 Jaipur Metro Rail 1.2.7 Signalling technology 2.2.6 Ecuador -

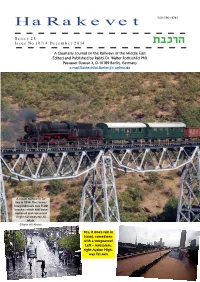

Issue No.107/4 December 2014 ,Cfrv

HaRakevet ISSN 0964-8763 Series 28 Issue No.107/4 December 2014 ,cfrv A Quarterly Journal on the Railways of the Middle East Edited and Published by Rabbi Dr. Walter Rothschild PhD Passauer Strasse 4, D-10789 Berlin, Germany e.mail:[email protected] A steam railtour in Tur- key in 2014. The former Kriegslok hauls two TCDD coaches which had been restored and repainted single-handedly by Ali Aksin. (Photo Ali Aksin). Yes, it does rain in Israel, sometimes with a vengeance! Left - Jerusalem, right Ayalon High- way Tel Aviv 107:0 concluded Tuesday morning with the ar- rests of over 5 managers and supervi- sors. According to police, the investiga- EDITORIAL tion – conducted with the full cooperation A bizarre change of emphasis in this issue. After moaning recently about the of Israel Railways CEO, Boaz Zafrir – de- lack of any positive news from most countries in the Middle East, the Editor found lots termined that the sanitation employees of information at Innotrans in Berlin and yet more in relation to proposed conferences colluded for months to commit bribery, (to which he could NOT go) in Dubai and Riyadh, discussing all sorts of fancy, expen- money laundering, fraud, and tax offenses sive and hi-tech projects throughout the region! Of course there is a major disconnect totaling “tens of millions” of shekels. between what one reads in the newspapers and what one sees as a serious discussion In a statement, police said the investi- about building tramways in Kurdistan. So a lot of this is presented here, in this issue, at gation was launched after suspicions were the expense of several historical items which have had to be held over to the next edi- raised that a number of sanitary inspectors tion. -

THE REPORT Saudi Arabia 2020

THE REPORT Saudi Arabia 2020 ECONOMY ICT JEDDAH INDUSTRY UTILITIES CAPITAL MARKETS ENERGY BANKING ENTERTAINMENT TRANSPORT EDUCATION INTERVIEWS www.oxfordbusinessgroup.com SPECIAL EDITION KIICO 0 4 3 8 1 5 2 1 9 1 8 7 9 CONTENTS SAUDI ARABIA 2020 5 49 Privatisation push: Dedicated framework ISBN 978-1-912518-52-4 supports a more cooperative approach between Editor-in-Chief: Oliver Cornock the government and investors Regional Editor, Middle East: Billy 51 Interview: Anas Alfaris, President, King Abdulaziz FitzHerbert City for Science and Technology Editorial Managers: Alban Serin, Eduardo Brandi, Carlos Ortega 52 Interview: Saad bin Othman Al Kasabi, Governor, Saudi Standards, Metrology and Quality Group Managing Editor: Laura Nelson Chief Sub-Editor: Tim Owens Organisation Deputy Chief Sub-Editors: Jennifer 53 Regional leader: The Kingdom is set to play a key Ma, Kayla Moser Senior Sub-Editor: Dominic Mealy role in strengthening global cooperation and Senior Sub-Editor, Digital: John Gray coordination Writer and Editor, Digital: Alex Pichaloff 55 Tax liabilities: Impacts of the trend towards Sub-Editors: Kevin Mataraci, Teresa lower corporate tax rates on developed and Meoni, Morgan Soares-Astbury, Lizzie Staying on course developing economies Waymouth Analysts: Lloyd Belton, Jade Currie, Page 41 TRADE & INVESTMENT Tom Hill, Andy Peters, Charles Phillips Real GDP grew by 0.3% in 2019, down from 2.2% 58 Global partnerships: Government support for Head of Research: Susan Manoğlu Editorial Researchers: Kasia Kuğay, in 2018. While this is a muted performance by economic diversification is set to substantially Beatriz Trigueros historical standards, some areas of the econ- increase opportunities for investment Group Creative Director: Yonca Ergin omy showed great promise: non-oil GDP ex- 62 Improved inflows: New initiatives are enhancing Art Editors: Catherine Celeste, Zahra panded by 3.3% during the year, and non-oil the appeal of the Kingdom to international Rashid Junior Graphic Associate: Babylynne private sector growth hit 3.8%, a five-year high. -

The Region's Premier Event to Focus on Capturing Emerging Opportunities

The region’s premier event to focus on capturing emerging opportunities in a fluctuating oil price era 8 – 9 November 2016, The Address Dubai Marina, Dubai, UAE Under the esteemed Patronage of: H.E. Dr. Abdullah Belhaif Al Nuaimi Minister of Infrastructure Development, Ministry of Infrastructure Development, UAE Chairman, Federal Transport Authority – Land & Maritime, UAE Hosted in partnership with: Gold sponsor: Silver sponsors: Bronze sponsors: The region’s premier event to focus on capturing emergingDraft Agenda: opportunities last updated - Monday, in a f luctuating05 September 2016oil p rice era Draft agenda: last updated - Monday, 05 September 2016 About the Summit The MENA Rail & Integrated Transport Summit is an annual high-end industry event hosted in Dubai and the largest project and opportunity focussed gathering of experts working in GCC, Middle East and North African rail, urban and integrated transport projects. Now in its 12th year, it delivers an exceptionally high level of seniority, with leading key decision makers and stakeholders from across MENA and beyond - Departments and Ministries of Transport, Operators and Regional Project Owners, PMCs and main contractors. The MENA Rail & Integrated Transport Summit is a platform to build momentum in moving the US$ 253bn (MEED Projects: 2016) urban transport and regional rail transportation goals forward. It incorporates a focused agenda exploring projects and key issues on projected urban transport & rail plans, project funding and ownership models, operability, GCC integration