Moving Words: Shifting Boundaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The World of Labour in Mughal India (C.1500–1750)

IRSH 56 (2011), Special Issue, pp. 245–261 doi:10.1017/S0020859011000526 r 2011 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis The World of Labour in Mughal India (c.1500–1750) S HIREEN M OOSVI Centre of Advanced Study in History, Aligarh Muslim University E-mail: [email protected] SUMMARY: This article addresses two separate but interlinked questions relating to India in Mughal times (sixteenth to early eighteenth century). First, the terms on which labour was rendered, taking perfect market conditions as standard; and, second, the perceptions of labour held by the higher classes and the labourers themselves. As to forms of labour, one may well describe conditions as those of an imperfect market. Slave labour was restricted largely to domestic service. Rural wage rates were depressed owing to the caste system and the ‘‘village community’’ mechanism. In the city, the monopoly of resources by the ruling class necessarily depressed wages through the market mechanism itself. While theories of hierarchy were dominant, there are indications sometimes of a tolerant attitude towards manual labour and the labouring poor among the dominant classes. What seems most striking is the defiant assertion of their status in relation to God and society made on behalf of peasants and workers in northern India in certain religious cults in the fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries. The study of the labour history of pre-colonial India is still in its infancy. This is due partly to the fact that in many respects the evidence is scanty when compared with what is available for Europe and China in the same period. -

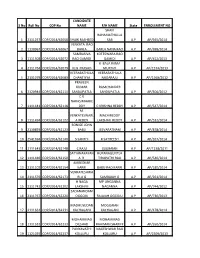

Visual Foxpro

RAJASTHAN ADVOCATES WELFARE FUND C/O THE BAR COUNCIL OF RAJASTHAN HIGH COURT BUILDINGS, JODHPUR Showing Complete List of Advocates Due Subscription of R.A.W.F. AT BHINDER IN UDAIPUR JUDGESHIP DATE 06/09/2021 Page 1 Srl.No.Enrol.No. Elc.No. Name as on the Roll Due Subs upto 2021-22+Advn.Subs for 2022-23 Life Time Subs with Int. upto Sep 2021 ...Oct 2021 upto Oct 2021 (A) (B) (C) (D) (E) (F) 1 R/2/2003 33835 Sh.Bhagwati Lal Choubisa N.A.* 2 R/223/2007 47749 Sh.Laxman Giri Goswami L.T.M. 3 R/393/2018 82462 Sh.Manoj Kumar Regar N.A.* 4 R/3668/2018 85737 Kum.Kalavati Choubisa N.A.* 5 R/2130/2020 93493 Sh.Lokesh Kumar Regar N.A.* 6 R/59/2021 94456 Sh.Kailash Chandra Khariwal L.T.M. 7 R/3723/2021 98120 Sh.Devi Singh Charan N.A.* Total RAWF Members = 2 Total Terminated = 0 Total Defaulter = 0 N.A.* => Not Applied for Membership, L.T.M. => Life Time Member, Termi => Terminated Member RAJASTHAN ADVOCATES WELFARE FUND C/O THE BAR COUNCIL OF RAJASTHAN HIGH COURT BUILDINGS, JODHPUR Showing Complete List of Advocates Due Subscription of R.A.W.F. AT GOGUNDA IN UDAIPUR JUDGESHIP DATE 06/09/2021 Page 1 Srl.No.Enrol.No. Elc.No. Name as on the Roll Due Subs upto 2021-22+Advn.Subs for 2022-23 Life Time Subs with Int. upto Sep 2021 ...Oct 2021 upto Oct 2021 (A) (B) (C) (D) (E) (F) 1 R/460/1975 6161 Sh.Purushottam Puri NIL + 1250 = 1250 1250 16250 2 R/337/1983 11657 Sh.Kanhiya Lal Soni 6250+2530+1250=10030 10125 25125 3 R/125/1994 18008 Sh.Yuvaraj Singh L.T.M. -

Prayer Cards | Joshua Project

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Adi Andhra in India Adi Dravida in India Population: 307,000 Population: 8,598,000 World Popl: 307,800 World Popl: 8,598,000 Total Countries: 2 Total Countries: 1 People Cluster: South Asia Dalit - other People Cluster: South Asia Dalit - other Main Language: Telugu Main Language: Tamil Main Religion: Hinduism Main Religion: Hinduism Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: Unknown % Evangelicals: Unknown % Chr Adherents: 0.86% Chr Adherents: 0.09% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible Source: Anonymous www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Dr. Nagaraja Sharma / Shuttersto "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Adi Karnataka in India Agamudaiyan in India Population: 2,974,000 Population: 888,000 World Popl: 2,974,000 World Popl: 906,000 Total Countries: 1 Total Countries: 2 People Cluster: South Asia Dalit - other People Cluster: South Asia Hindu - other Main Language: Kannada Main Language: Tamil Main Religion: Hinduism Main Religion: Hinduism Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: Unknown % Evangelicals: Unknown % Chr Adherents: 0.51% Chr Adherents: 0.50% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Anonymous Source: Anonymous "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Agamudaiyan Nattaman -

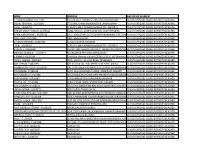

S No Roll No COP No CANDIDATE NAME F/H NAME State

CANDIDATE S No Roll No COP No NAME F/H NAME State ENROLLMENT NO SHAIK RAHAMATHULLA 1 2111257 COP/2014/62058 SHAIK RASHEED SAB A.P AP/945/2014 VENKATA RAO 2 1130967 COP/2014/62067 BARLA BARLA NANA RAO A.P AP/698/2014 SAMBASIVA KOTESWARA RAO 3 1111308 COP/2014/62072 RAO GAMIDI GAMIDI A.P AP/452/2013 K BALA RAMA 4 2111764 COP/2014/62079 KLN PRASAD MURTHY A.P AP/1574/2013 VEERABATHULA VEERABATHULA 5 2131079 COP/2014/62083 CHANTIYYA NAGARAJU A.P AP/1568/2012 PRAVEEN KUMAR RAMCHANDER 6 2120944 COP/2014/62111 SANDUPATLA SANDUPATLA A.P AP/306/2012 C V NARASIMHARE 7 1111441 COP/2014/62118 DDY C KRISHNA REDDY A.P AP/547/2014 M. VENKATESWARL MACHIREDDY 8 1111494 COP/2014/62122 A REDDY LAKSHMI REDDY A.P AP/532/2014 BONIGE JOHN 9 2130893 COP/2014/62123 BABU JEEVARATNAM A.P AP/878/2014 10 2541694 COP/2014/62140 S SANTHI R SATHEESH A.P AP/267/2014 11 2111643 COP/2014/62148 C RAJU SUGRAIAH A.P AP/1238/2011 SATYANARAYAN RUPANAGUNTLA 12 1111480 COP/2014/62150 A R. TIRUPATHI RAO A.P AP/540/2014 AMBEDKAR 13 2131102 COP/2014/62154 KARRI BABU RAO KARRI A.P AP/180/2014 VENKATESHWA 14 2111570 COP/2014/62173 RLU G SAMBAIAH G A.P AP/261/2014 H NAGA MP LINGANNA 15 2111742 COP/2014/62202 LAKSHMI NAGANNA A.P AP/744/2012 SADANANDAM 16 2111767 COP/2014/62220 OGGOJU RAJAIAH OGGOJU A.P AP/736/2013 MADHUSUDAN MOGILAIAH 17 2111661 COP/2014/62231 KACHAGANI KACHAGANI A.P AP/478/2014 MOHAMMAD MOHAMMAD 18 1111532 COP/2014/62233 DILSHAD RAHIMAN SHARIFF A.P AP/550/2014 PUNYAVATHI NAGESHWAR RAO 19 1121035 COP/2014/62237 KOLLURU KOLLURU A.P AP/2309/2013 G SATHAKOTI GEESALA 20 2131021 COP/2014/62257 SRINIVAS NAGABHUSHANAM A.P AP/1734/2011 GANTLA GANTLA SADHU 21 1131067 COP/2014/62258 SANYASI RAO RAO A.P AP/1802/2013 KOLICHALAM NAVEEN KOLICHALAM 22 1111688 COP/2014/62265 KUMAR BRAHMAIAH A.P AP/1908/2010 SRINIVASA RAO SANKARA RAO 23 2131012 COP/2014/62269 KOKKILIGADDA KOKKILIGADDA A.P AP/793/2013 24 2120971 COP/2014/62275 MADHU PILLI MAISAIAH PILLI A.P AP/108/2012 SWARUPARANI 25 2131014 COP/2014/62295 GANJI GANJIABRAHAM A.P AP/137/2014 26 2111507 COP/2014/62298 M RAVI KUMAR M LAXMAIAH A.P AP/177/2012 K. -

Shah-Jo-Risalo (Selections)

RISALO OF SHAH ABDUL LATIF (SELECTIONS) TRANSLATED IN VERSE BY ELSA KAZI COMPILIED IN E-BOOK BY JUNAID JAMSHAID I.T.SCHOLARS GROUP LARKANA, SINDH, PAKISTAN. www.itsgrouplrk.com [email protected] Ph.#. 074-4046864-4058075 Shah-jo-Risalo A word about the author: Elsa Kazi By: Ali Ahmed K Brohi Mrs. Allama Kazi who called by all as Mother Elsa Kazi, was a remarkable woman indeed. She was German by birth, but a Sindhi by spirit and God had bestowed upon her the grace of being one of the greatest poets of her time. She was not only a poet of very high caliber, but painter of great distinction, besides she was a writer of repute - she wrote one- act plays, short stories, plays, novels and history. She was a composer and a musician of considerable attainments. Indeed, there was hardly any conspicuous branch of Fine Arts that she did not practice to perfection. Although she did not know Sindhi language directly but still she managed to produce translation in English verse of the selected verses of Shah Abdul Latif after the pith and substance of the meaning of those verses were explained to her by Allama Kazi. She has successfully couched the substance of those verses in a remarkable poetical setting which, in musical terms, reflects the echo of the original Sindhi metrical structure and expression in which Latif had cast them. Her's remains the best translation so far in English of Shah Abdul Latif's Translated In Verse By Elsa Kazi www.itsgrouplrk.com Shah-jo-Risalo poetry. -

Sindhi Community – Shiv Sena

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: IND30284 Country: India Date: 4 July 2006 Keywords: India – Maharashtra – Sindhi Community – Shiv Sena This response was prepared by the Country Research Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Questions 1. Is there any independent information about any current ill-treatment of Sindhi people in Maharashtra state? 2. Is there any information about the authorities’ position on any ill-treatment of Sindhi people? RESPONSE 1. Is there any independent information about any current ill-treatment of Sindhi people in Maharashtra state? Executive Summary Information available on Sindhi websites, in press reports and in academic studies suggests that, generally speaking, the Sindhi community in Maharashtra state are not ill-treated. Most writers who address the situation of Sindhis in Maharashtra generally concern themselves with the social and commercial success which the Sindhis have achieved in Mumbai (where the greater part of the Sindh’s Hindu populace relocated after the partition of India and Pakistan). One news article was located which reported that the Sindhi community had been targeted for extortion, along with other “mercantile communities”, by criminal networks affiliated with Maharashtra state’s Sihiv Sena organisation. -

Makers-Of-Modern-Sindh-Feb-2020

Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh SMIU Press Karachi Alma-Mater of Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah Sindh Madressatul Islam University, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000 Pakistan. This book under title Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honour MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Written by Professor Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh 1st Edition, Published under title Luminaries of the Land in November 1999 Present expanded edition, Published in March 2020 By Sindh Madressatul Islam University Price Rs. 1000/- SMIU Press Karachi Copyright with the author Published by SMIU Press, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000, Pakistan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any from or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passage in a review Dedicated to loving memory of my parents Preface ‘It is said that Sindh produces two things – men and sands – great men and sandy deserts.’ These words were voiced at the floor of the Bombay’s Legislative Council in March 1936 by Sir Rafiuddin Ahmed, while bidding farewell to his colleagues from Sindh, who had won autonomy for their province and were to go back there. The four names of great men from Sindh that he gave, included three former students of Sindh Madressah. Today, in 21st century, it gives pleasure that Sindh Madressah has kept alive that tradition of producing great men to serve the humanity. -

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts Shahnaz Begum Laghari PhD University of York Women’s Studies March 2016 Abstract The aim of this project is to investigate the phenomenon of honour-related violence, the most extreme form of which is honour killing. The research was conducted in Sindh (one of the four provinces of Pakistan). The main research question is, ‘Are these killings for honour?’ This study was inspired by a need to investigate whether the practice of honour killing in Sindh is still guided by the norm of honour or whether other elements have come to the fore. It is comprised of the experiences of those involved in honour killings through informal, semi- structured, open-ended, in-depth interviews, conducted under the framework of the qualitative method. The aim of my thesis is to apply a feminist perspective in interpreting the data to explore the tradition of honour killing and to let the versions of the affected people be heard. In my research, the women who are accused as karis, having very little redress, are uncertain about their lives; they speak and reveal the motives behind the allegations and killings in the name of honour. The male killers, whom I met inside and outside the jails, justify their act of killing in the name of honour, culture, tradition and religion. Drawing upon interviews with thirteen women and thirteen men, I explore and interpret the data to reveal their childhood, educational, financial and social conditions and the impacts of these on their lives, thoughts and actions. -

The Rise of Dalit Peasants Kolhi Activism in Lower Sindh

The Rise of Dalit Peasants Kolhi Activism in Lower Sindh (Original Thesis Title) Kolhi-peasant Activism in Naon Dumbālo, Lower Sindh Creating Space for Marginalised through Multiple Channels Ghulam Hussain Mahesar Quaid-i-Azam University Department of Anthropology ii Islamabad - Pakistan Year 2014 Kolhi-Peasant Activism in Naon Dumbālo, Lower Sindh Creating Space for Marginalised through Multiple Channels Ghulam Hussain Thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology, Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad, in partial fulfillment of the degree of ‗Master of Philosophy in Anthropology‘ iii Quaid-i-Azam University Department of Anthropology Islamabad - Pakistan Year 2014 Formal declaration I hereby, declare that I have produced the present work by myself and without any aid other than those mentioned herein. Any ideas taken directly or indirectly from third party sources are indicated as such. This work has not been published or submitted to any other examination board in the same or a similar form. Islamabad, 25 March 2014 Mr. Ghulam Hussain Mahesar iv Final Approval of Thesis Quaid-i-Azam University Department of Anthropology Islamabad - Pakistan This is to certify that we have read the thesis submitted by Mr. Ghulam Hussain. It is our judgment that this thesis is of sufficient standard to warrant its acceptance by Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad for the award of the degree of ―MPhil in Anthropology‖. Committee Supervisor: Dr. Waheed Iqbal Chaudhry External Examiner: Full name of external examiner incl. title Incharge: Dr. Waheed Iqbal Chaudhry v ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This thesis is the product of cumulative effort of many teachers, scholars, and some institutions, that duly deserve to be acknowledged here. -

Baroda, Imperial Tables, Part II, Vol-XVI-A

CENSUS OF INDIA, 19II. VOLUME XVI-A. ... - BARODA STATE. 1.' PART II. THE IMPERIAL TABLES BY OOVIN 0 BHAI H. DESAI, B.A., LL. B., SUPE~INTBNDENT OF CENSUS OPE~TIONS, BARODA STATE. PRINTED AT THE TIMES PRESS. 191 J. Price-Indian, Os. 3; Ellglish, 'Is. TABLE OF CON'rENTS. PAGlI. TABLE I-AREA, Hou8ES AND POI'ULA'l'IO"" • ••• 1 VABIA'l.'IO~ IN POPULA'l'ION ~~E ~ iii: ......- .. .,' _ " Il- 1872 ". .... 3 III-ToWNS AND VILJ.AGES GI,AS.. rfED BY POPULATION -:: .... r~~ ••• 7 " •••• 40 0 ' . of , .. IV-ToWNIi OLASSI!i'IED NY PnI'UI'A'tiq~, #iTH' .vAW7'iON, surOB 1872 ••• 9 " o 'Ii.... •. I· ....... V-TowNs ABRANGFJD TgnmTORIALLY ;;ifir FOPu1.iATi:~ BY RBLIOION ••• 13 " VI-RELIGION " 00. 17 VII-A(m, SEX AND OIVII. ()ONDITION- " Part A-Provincial Smumllry 20 .. l1-Details for Districts 24 C-Detail,; for the City of Baroda 38 " VllI-EDUCATION BY HELIGION AND AGE- Part ... I-Provincial Summary 38 ., B-Detnils for Districts .. ... ... 39 C-Details for tlw City of Bnroda 42 " IX-EDUCA'l'ION BY SElEOTED C:As'rES, TRIBES OR RAOE!! 43 " X-LANGUAGE 47 " ... XI-BIRT1{~PLACE 53 " ... XII-h~'IR)IITmS- " Part I-Di~h'ihntion by Age ... 64 ,. II-Distrihution by District~ 64: " XIIA-bFIllMI'rIES BY f;ELJoJGTED CASTES, TRlBES on RAOES 65 " XIII-CAS'I'E, TRIBE, RAOE OR ~ATlONAMTY- Pl.ut A-Hindu:;, ,Jains, Animists and Arya Samajists 70 ' " B-}!u~hnan~ 00. -80 XIV-CIVIL CONDITION BY Am;: FOR KELEO'l'ED CASTES 83 " XV-OCOUPATION OR }!EAXS OF IJIVIiLIHoon !n " Part A-Heneml Tahle 92 " B-Hl1bsidillry Occupations of' Agricultul'ists- Actnal Workers only (1) Hent Receivers . -

Name Address Nature of Payment P

NAME ADDRESS NATURE OF PAYMENT P. NAVEENKUMAR -91774443 NO 139 KALATHUMEDU STREETMELMANAVOOR0 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED VISHAL TEKRIWAL -31262196 27,GOPAL CHANDRAMUKHERJEE LANEHOWRAH CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED LOCAL -16280591 #196 5TH MAIN ROADCHAMRAJPETPH 26679019 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED BHIKAM SINGH THAKUR -21445522 JABALPURS/O UDADET SINGHVILL MODH PIPARIYA CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED ATINAINARLINGAM S -91828130 NO 2 HINDUSTAN LIVER COLONYTHAGARAJAN STREET PAMMAL0CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED USHA DEVI -27227284 VPO - SILOKHARA00 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED SUSHMA BHENGRA -19404716 A-3/221,SECTOR-23ROHINI CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED LOCAL -16280591 #196 5TH MAIN ROADCHAMRAJPETPH 26679019 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED RAKESH V -91920908 NO 304 2ND FLOOR,THIRUMALA HOMES 3RD CROSS NGRLAYOUT,CLAIMS CHEQUES ROOPENA ISSUED AGRAHARA, BUT NOT ENCASHED KRISHAN AGARWAL -21454923 R/O RAJAPUR TEH MAUCHITRAKOOT0 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED K KUMAR -91623280 2 nd floor.olympic colonyPLOT NO.10,FLAT NO.28annanagarCLAIMS west, CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED MOHD. ARMAN -19381845 1571, GALI NO.-39,JOOR BAGH,TRI NAGAR0 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED ANIL VERMA -21442459 S/O MUNNA LAL JIVILL&POST-KOTHRITEH-ASHTA CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED RAMBHAVAN YADAV -21458700 S/O SURAJ DEEN YADAVR/O VILG GANDHI GANJKARUI CHITRAKOOTCLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED MD SHADAB -27188338 H.NO-10/242 DAKSHIN PURIDR. AMBEDKAR NAGAR0 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED MD FAROOQUE -31277841 3/H/20 RAJA DINENDRA STREETWARD NO-28,K.M.CNARKELDANGACLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED RAJIV KUMAR -13595687 CONSUMER APPEALCONSUMERCONSUMER CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED MUNNA LAL -27161686 H NO 524036 YARDS, SECTOR 3BALLABGARH CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED SUNIL KUMAR -27220272 S/o GIRRAJ SINGHH.NO-881, RAJIV COLONYBALLABGARH CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED DIKSHA ARORA -19260773 605CELLENO TOWERDLF IV CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED R. -

Sympathy and the Unbelieved in Modern Retellings of Sindhi Sufi Folktales

Sympathy and the Unbelieved in Modern Retellings of Sindhi Sufi Folktales by Aali Mirjat B.A., (Hons., History), Lahore University of Management Sciences, 2016 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Aali Mirjat 2018 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2018 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Approval Name: Aali Mirjat Degree: Master of Arts Title: Sympathy and the Unbelieved in Modern Retellings of Sindhi Sufi Folktales Examining Committee: Chair: Evdoxios Doxiadis Assistant Professor Luke Clossey Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Bidisha Ray Co-Supervisor Senior Lecturer Derryl MacLean Supervisor Associate Professor Tara Mayer External Examiner Instructor Department of History University of British Columbia Date Defended/Approved: July 16, 2018 ii Abstract This thesis examines Sindhi Sufi folktales as retold by five “modern” individuals: the nineteenth- century British explorer Richard Burton and four Sindhi intellectuals who lived and wrote in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries (Lilaram Lalwani, M. M. Gidvani, Shaikh Ayaz, and Nabi Bakhsh Khan Baloch). For each set of retellings, our purpose will be to determine the epistemological and emotional sympathy the re-teller exhibits for the plot, characters, sentiments, and ideas present in the folktales. This approach, it is hoped, will provide us a glimpse inside the minds of the individual re-tellers and allow us to observe some of the ways in which the exigencies of a secular western modernity had an impact, if any, on the choices they made as they retold Sindhi Sufi folktales.