T H a I L a N D State of Environment the Decade of 1990S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gulfofthailand

Ban Sa Khok Pip Wang Lam 348 BANGKOK Khoi Talu Pra 3076 304 chi Sa Kaew Minburi 304 319 n 3200 bur Watthana Ang Sila Non Mak Mun Ratchasan Phanom Nakhon Lat Krabang Sarakham i Huay Jot g Sai Yoi 33 on 317 C A M B O D I A k Aranya Prathet Chachoengsao Pa 304 Kha Pa Khao Chakan SAMUT Bang Sanam Chai Poipet Khet Ngam 3395 PRAKAN Ban Pho Khlong 314 Sai Diaw Non Sao-Eh Plaeng Yao Sisophon e Nam a Si Muang Boran M 315 Yot (Ancient City) 331 CHACHOENGSAO Khlong Hat 3 Phanat Nikhom Khao Takrup Chum Num (660m) Wang Mai Prok Fa Chonburi 3395 344 Nong Samet Ban Bung 317 Ao Krung Thep Bo Thong Khao Yai (Bay of Bangkok) (777m) Khao Daeng CHONBURI Thun Ko Si Khanan Chang Si Racha Lum Borai Nong Yai 3 Laem Chabang Map Yang CHANTHABURI Tamun Battambang 344 Khao Soi Dao Nua Ko (1566m) Phai Pung Ngon Khao Chamao Nong Chek Soi Wang (1024m) Takra Ban Pakard Pattaya g n Chang Khao Chamao/ Nong Pong Nam Psar Pruhm Ko Lan Samet Khao Wong Khao Khitchakut Ron 3191 RAYONG National Park 331 36 Rayo National Park Pailin Si Yaek Ao Ban Sare 317 Ban Klaeng Kong Din 3 Chang Khlong 3 3 Nong Khla Ko Kham Laem Mae Yai Rayong Sattahip Phim Makham U-Taphao 3 Ban Pa-Ah Airfield Ko Ban Phe Ko Man Nai Tha Mai Chanthaburi Chang Thun Samae Saket Ko Thalu Nong Ko Samaesan Ko Samet Nam Tok Phlio Ko Kudee Laem Sadet National Park Sii Ta Chalap 3157 Chak Yai Ko Chuang Khao Laem Ya/ Laem Singh Mu Ko Samet National Park Khlung Pong Dan Chumpon Laem Ko Proet 3159 Tha Chot 3271 TRAT 3156 3 Trat C A M B O D I A Bang Kradan Ban Noen Sung Laem Muang Laem Ngop 318 Ao Trat Tha Sen G U L F O F Ko Chang Laem Sok T H A I L A N D Mu Ko Chang National Marine Park Mai Rut Ko Wai Ko Kradat 0 50 km Ko Rayang Ko Mak 0 30 miles Khlong Yai Ko Mai Si Ko Kut Hat Lek Krong Koh Kong. -

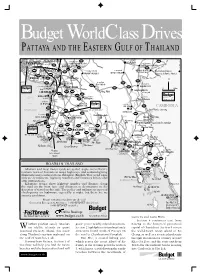

Budgetworldclassdrives

Budget WorldClass Drives PATTAYA AND THE EASTERN GULF OF THAILAND √–·°â« BANG NAM PRIED Õ.æπ¡ “√§“¡ 319 348 PHANOM SARAKHAM SA KAEO Õ.«—≤π“π§√ BANGKOK Õ.∫“ßπÈ”‡ª√’Ȭ« 304 Õ.∫“ߧ≈â“ BANG KHLA WATTHANA NAKHON 3245 33 3121 9 CHACHOENGSAO 304 Õ. π“¡™—¬‡¢µ Õ.‡¢“©°√√®å ARANYAPRATHET International Border Oliver Hargreave ©–‡™‘߇∑√“ 304 KHA0 CHAKAN Õ.Õ√—≠ª√–‡∑» 7 SANAMCHAI KHET Crossing & Border Market 3268 BANG BO Õ.∫â“π‚æ∏‘Ï 34 BAN PHO BANG PHLI Õ.∫“ß∫àÕ PLAENG YAO N Õ.∫“ßæ≈’ Õ.·ª≈߬“« 3395 Õ.æ“π∑Õß ∑à“µ–‡°’¬∫ 3 PHAN THONG 3434 Õ.§≈ÕßÀ“¥ 3259 THA TAKIAP Õ.∫“ߪ–°ß BANG PHANAT NIKHOM 3067 KHLONG HAT PAKONG 3259 0 20km ™≈∫ÿ√’ Õ.æπ— π‘§¡ WANG SOMBUN CHONBURI 349 331 Nong Khok Õ.«—ß ¡∫Ÿ√≥å 344 3245 BANG SAEN 3340 Õ.∫àÕ∑Õß G U L F BAN BUNG ∫.∑ÿàߢπ“π ∫“ß· π Õ.∫â“π∫÷ß 3401 BO THONG Thung Khanan Õ.»√’√“™“ O F SI RACHA Õ.ÀπÕß„À≠à Õ. Õ¬¥“« NONG YAI SOI DAO 3406 C A M B O D I A 3 T H A I L A N D 3138 3245 Tel: (0) 3895 4352 Local border crossing 7 Soi Dao Falls 344 317 Õ.∫“ß≈–¡ÿß 2 Bo Win Õ.ª≈«°·¥ß Khao Chamao Falls BAN LAMUNG PLUAK DAENG Khlong Pong Nam Ron Rafting Ko Lan Krathing 1 Khao Wong PONG NAM RON Local border crossing 3191 WANG CHAN 3377 Õ.‚ªÉßπÈ”√âÕπ Pattaya City 3 36 3471 «—ß®—π∑√å Õ.∫â“π©“ß Õ.∫â“π§à“¬ Õ.·°≈ß Khiritan Dam 3143 KLAENG BAN CHANG BAN KHAI 4 3 3138 3220 Tel: (0) 3871 0717-8 3143 MAKHAM Ko Khram √–¬Õß Õ.¡–¢“¡ Ban Noen RAYONG ®—π∑∫ÿ√’ Tak Daet SATTAHIP 3 Ban Phe Laem Õ.∑à“„À¡à Õ. -

Report of Thailand on Cartographic Activities During the Period of 2007-2009*

UNITED NATIONS E/CONF.100/CRP.15 ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COUNCIL Eighteenth United Nations Regional Cartographic Conference for Asia and the Pacific Bangkok, 26-29 October 2009 Item 7(a) of the provisional agenda Country Reports Report of Thailand on Cartographic Activities * During the Period of 2007-2009 * Prepared by Thailand Report of Thailand on Cartographic Activities During the Period of 2007-2009 This country report of Thailand presents in brief the cartographic activities during the reporting period 2007-2009 performed by government organizations namely Royal Thai Survey Department , Hydrographic Department and Meteorological Department. The Royal Thai Survey Department (RTSD) The Royal Thai Survey Department is the national mapping organization under the Royal Thai Armed Forces Headquarters , Ministry of Defense. Its responsibilities are to survey and to produce topographic maps of Thailand in support of national security , spatial data infrastructure and other country development projects. The work done during 2007-2009 is summarized as follows. 1. Topographic maps in Thailand Topographic maps in Thailand were initiated in the reign of King Rama the 5th. In 1868, topographic maps covering border area on the west of Thailand were carried out for the purpose of boundary demarcation between Thailand and Burma. Collaboration with western countries, maps covering Bangkok and Thonburi were produced. During 1875, with farsighted thought in country development, King Rama the 5th established Topographic Department serving road construction in Bangkok and set up telecommunication network from Bangkok to Pratabong city. Besides, during this period of time, maps covering Thai gulf were produced serving marine navigation use. In 1881, Mr. Mcarthy from the United Kingdom was appointed as director of Royal Thai Survey Department (RTSD), previously known as Topographic Department, and started conducting Triangulation survey in Thailand. -

Reference Information

267 ANNUAL REPORT 2014 KASIKORNBANK REFERENCE INFORMATION KASIKORNBANK PUBLIC COMPANY LIMITED conducts commercial banking business, securities business, and other related business under the Financial Institution Business Act, Securities and Exchange Act and other related regulations. Head Office : 1 Soi Rat Burana 27/1, Rat Burana Road, Rat Burana Sub-District, Rat Burana District, Bangkok 10140, Thailand Company Registration Number : 0107536000315 (formerly PLC 105) Telephone : +662-2220000 Fax : +662-4701144-5 K-Contact Center (Personal) : +662-8888888 Press 1 Thai, Press 2 Mandarin, Press 3 English, Press 4 Japanese, Press 5 Myanmar K-BIZ Contact Center (Business) : +662-8888822 Press 1 Thai, Press 2 Mandarin, Press 3 English, Press 4 Japanese, Press 5 Myanmar SWIFT : KASITHBK E-mail : [email protected] Website : www.kasikornbank.com Names, Offices, Telephone and Fax Numbers of Referenced Entities Registrar - Ordinary Shares : Thailand Securities Depository Company Limited 62 The Stock Exchange of Thailand Building, Ratchadaphisek Road, Klong Toei District, Bangkok 10110, Thailand Tel. +662-2292800 Fax +662-3591259 TSD Call Center: +662-2292888 e-mail: [email protected] Website: www.tsd.co.th - KASIKORNBANK PCL Subordinated Debentures : KASIKORNBANK PUBLIC COMPANY LIMITED No. 1/2010, due for redemption in 2020 1 Soi Rat Burana 27/1, Rat Burana Road, - KASIKORNBANK PCL Subordinated Debentures Rat Burana Sub-District, Rat Burana District, Bangkok 10140, Thailand No. 1/2012, due for redemption in 2022 Tel. +662-2220000 Fax +662-4701144-5 - Subordinated Instruments intended to qualify as Tier 2 Capital of KASIKORNBANK PCL No. 1/2014 due 2025 - KASIKORNBANK PCL 8 1/4% Subordinated : The Bank of New York Mellon, One Wall Street New York, N.Y. -

Integral Study of the Silk Roads: Roads of Dialogue

INTEGRAL STUDY OF THE SILK ROADS: ROADS OF DIALOGUE 21-22 JANUARY 1991 BANGKOK, THAILAND Document No. 1 6 Maritime Trade during the 14th and the 17th Century: Evidence from the Underwater Archaeological Sites In the Gulf of Siam Mr. Sayan Prichanchit 1 Maritime Trade during the 14th and the 17th Century: Evidence from the Underwater Archaeological Sites in the Gulf of Siam Sayan Prichanchit Introduction The catchword in today's transportation field is convenience. Journeys to distant continents which might be thousands of miles away can be made within hours in aircrafts that have been developed to achieve supersonic speed. However, the high cost of airfreight discourages merchants from using it to transport heavy and bulky cargo which is more economically moved by sea-faring vessels - a mode of transport which has been utilized by merchants for thousands of years. Ships can sail at much higher speeds and can carry tens of thousands of tons in this modern era, but they also continue to provide housing and office space for all of those who sail them in much the same way that they have in the past. All of the activities of man's daily life are still squeezed on board. There is evidence to suggest that sea traders from afar were present on the river plains in central Thailand and along the coast of the Gulf of Siam down to the Malay Peninsula since the 4th or 5th century. During the 7th to the 11th centuries when human settlement had become more prominent, with the Dvaravati Kingdom controlling much of central Thailand and the Srivijaya Kingdom's territory covering the Malay Peninsula and the Indonesian Archipelago, evidence of maritime trade routes include ceramics from China, glass and stone beads from India and Persia, and cult icons, all of which had been carried to the region by these maritime traders and introduced to the indigenous people. -

Thailand's Islands & Beaches E0 100 Miles

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Thailand’s Islands & Beaches Bangkok #_ p66 Ko Chang & the Eastern Seaboard p118 Hua Hin & the Upper Gulf p160 Ko Samui & the Lower Gulf p193 Phuket & the Andaman Coast p263 Damian Harper, Tim Bewer, Austin Bush, David Eimer, Andy Symington PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to Thailand’s BANGKOK . 66 HUA HIN & Islands & Beaches . 4 THE UPPER Thailand’s Islands & GULF . 160 Beaches Top 18 . 8 KO CHANG & THE EASTERN Phetchaburi . 162 Need to Know . 18 SEABOARD . 118 Kaeng Krachan First Time Thailand’s National Park . 166 Si Racha . 119 Islands & Beaches . 20 Cha-am . 168 Ko Si Chang . 123 What’s New . 22 Hua Hin . 170 Bang Saen . 124 If You Like . 23 Pranburi Pattaya . 125 Month by Month . 25 & Around . 178 Rayong & Ban Phe . 131 Itineraries . 28 Khao Sam Roi Yot Ko Samet . 131 National Park . 180 Responsible Travel . 36 Chanthaburi . 137 Prachuap Choose Your Beach . 39 Trat . 141 Khiri Khan . 181 Diving & Snorkelling . 47 Ko Chang . 144 Ban Krut & Bang Saphan Yai . 186 Eat & Drink Ko Kut . 155 Like a Local . 52 Chumphon . 188 Ko Mak . 157 Travel with Children . 60 Regions at a Glance . 63 PANATFOTO / SHUTTERSTOCK © SHUTTERSTOCK / PANATFOTO CATHERINE SUTHERLAND / LONELY PLANET © PLANET LONELY / SUTHERLAND CATHERINE KO PHI-PHI DON P333 ANEKOHO / SHUTTERSTOCK © SHUTTERSTOCK / ANEKOHO KAYAKING IN KO KUT P155 SNORKELLING IN KO CHANG P146 Contents UNDERSTAND KO SAMUI & THE Ko Phra Thong Thailand’s Islands & LOWER GULF . 193 & Ko Ra . 277 Beaches Today . 374 Khao Lak & Around . .. 278 Gulf Islands . 196 History . 376 Ko Samui . 196 Similan Islands People & Society . -

Seaside Paradise Top 50 Beaches & Islands in Thailand

Seaside Paradise Top 50 beaches & islands in Thailand. The Indochinese peninsula is a magical land ranking second to none. Two oceans run parallel to the coastline spanning an impressive distance of more than 2,600 kilometres. More than 900 islands and islets dot the waters off the expansive coasts and enjoy the embrace of the gorgeous turquoise blue ocean. Taking the time to explore even just a tiny fraction of the seas and beaches in Thailand will provide you with a personal, magical and unforgettable experience. Taking in the picturesque landscape and a blissful journey along the Indochinese peninsula is one travel experience sure to provide you with fond memories that will remain dear to your heart for years to come. “Seaside Paradises” is a compilation of colourful accounts from various seaside destinations in Thailand. Let this guide lead you and your family on an unforgettable journey accompanied by the sea breezes at your back and the sun on your shoulder. The gorgeous tropical colours of the beaches, fun activities for couples, and simple indulgences that Mother Nature alone can provide for are sure to create the perfect atmosphere for a remarkable tropical holiday. Contents Bangkok NATURAL Beaches Page ROMANTIC Beaches Page 1 Ko Kham, Chon Buri Province 8 15 Ko Kut, Trat Province 54 36 Pattaya 2 Ko Samae San, Chon Buri Province 10 16 Ko Mak, Trat Province 58 37 Hua Hin 46 3 Hat Sam Roi Yot, Prachuap Khiri Khan Province 12 17 Hat Khung Wiman, Chanthaburi Province 60 47 20 45 4 Mu Ko Ang Thong, Surat Thani Province 14 18 Ko Man -

Thailand Ko Chang & Eastern Seaboard (Chapter)

Thailand Ko Chang & Eastern Seaboard (Chapter) Edition 14th Edition, February 2012 Pages 41 PDF Page Range 191-231 Coverage includes: Si Racha, Ko Si Chang, Pattaya, Rayong & Ban Phe, Ko Samet, Chanthaburi, Ko Wai, Ko Mak, and Ko Kut. Useful Links: Having trouble viewing your file? Head to Lonely Planet Troubleshooting. Need more assistance? Head to the Help and Support page. Want to find more chapters? Head back to the Lonely Planet Shop. Want to hear fellow travellers’ tips and experiences? Lonely Planet’s Thorntree Community is waiting for you! © Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd. To make it easier for you to use, access to this chapter is not digitally restricted. In return, we think it’s fair to ask you to use it for personal, non-commercial purposes only. In other words, please don’t upload this chapter to a peer-to-peer site, mass email it to everyone you know, or resell it. See the terms and conditions on our site for a longer way of saying the above - ‘Do the right thing with our content. ©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Ko Chang & Eastern Seaboard Why Go? Si Racha .......................194 Bangkok Thais have long escaped the urban grind with Ko Si Chang ................. 196 weekend escapes to the eastern seaboard. Some of the coun- Pattaya .........................197 try’s fi rst beach resorts sprang up here, starting a trend that Rayong & Ban Phe .......204 has been duplicated wherever sand meets sea. As the coun- try became industrialised, only a few, like Ko Samet beaches, Ko Samet .....................205 remain spectacular specimens within reach of the capital. -

Geology and Mineral Deposits of Thailand by I

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Geology and mineral deposits of Thailand by I/ D. R. Shawe Open-File Report 84- Prepared on behalf of the Government of Thailand and the Agency for International Development, U.S. Department of State. This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature, _]/ U.S. Geological Survey, Denver CO 80225 1984 CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION.......................................................... 1 GEOLOGY OF THAILAND................................................... ? Stratigraphy of sedimentary rocks................................ 4 Precambrian................................................. 4 Cambrian.................................................... 6 Ordovician.................................................. 7 Silurian-Devonian........................................... I0 Carboniferous............................................... 16 Permian..................................................... 20 Triassic.................................................... 25 Jurassic.................................................... 29 Cretaceous.................................................. 32 Tertiary................................^................... 33 Quaternary.................................................. 35 Igneous rocks.................................................... 36 Precambrian. ................................................. 36 Silurian-Devonian. .......................................... -

INTRODUCTION Litsea Is One of the Largest Genera in the Family

THAI FOR. BULL. (BOT.) 39: 40–119. 2011. A revision of the genus Litsea Lam. (Lauraceae) in Thailand CHATCHAI NGERNSAENGSARUAY*, DAVID J. MIDDLETON** & KONGKANDA CHAYAMARIT*** ABSTRACT. A taxonomic revision of the genus Litsea in Thailand is presented. Thirty-five species of Thai Litsea are included in this treatment. A key to the species is presented, nomenclatural information is provided, all names are typified, and all species are described. Distribution and ecological data as available are provided. INTRODUCTION medium-sized trees, or occasionally shrubs. The trees can be divided by height into 3 groups as Litsea is one of the largest genera in the follows: small trees (3–10 m), medium-sized trees family Lauraceae, the species of which form an (10–20 m) and large trees (20–30 m). important component of tropical forests. It is estimated that there are over 300 species, mostly in A shrubby habit is found in Litsea phuwuaensis tropical Asia but with a few species in the islands (0.5–2.5 m). Litsea hirsutissima (1–5 m), L. lancifolia of the Pacific, Australia and in North and Central (2–8 m), L. mollis (1.5–6 m) and L. nuculanea (2–5 America (Van der Werff, 2001). The most significant m) can be shrubs or small trees. Litsea umbellata recently published regional revisions are for China (1–13 m) ranges from being a shrub to a medium- with 74 species (Huang et al., 2008) and Nepal sized tree. with 11 species (Pendry, 2011). Litsea hookeri (8 m), L. johorensis (3–8 m), In Thailand, there are few references on this L. -

Simply Thailand (04 Nights / 05 Days)

(Approved By Ministry of Tourism, Govt. of India) Simply Thailand (04 Nights / 05 Days) Routing : Phuket (2N) – Bangkok (2N) Day 01 : Arrive Thailand onto Pattaya the beach city. On arrival in Bangkok after immigration clearance and baggage collection, you will be met by our local representative and transfer to Pattaya. Arrive & Check in to Hotel (check-in after 1400 Hrs). Day is free for optional activities. Overnight at hotel in Pattaya. Day 02 : Coral Island With Indain Lunch After breakfast at the hotel, get set to explore the charm and beauty of Coral Island (subject to weather conditions) where you can enjoy water sports activities like parasailing, snorkelling, windsurfing etc. Coral Island (Koh Lan) is the largest of the "near islands", off south Pattaya. It is at the southeast end of the Bay of Bangkok, on the east side of the Gulf of Siam. Administratively Ko Lan belongs to the Amphoe Bang Lamung, Chonburi. Most of Ko Lan's beaches are on its west side. Most visited is Tawaen Beach, where there is a small harbor. You will enjoy the sea, sun sand and the length of the beach is lined with small tourist shops. Day is free for optional activities. Overnight at hotel in Pattaya. Day 03 : Onto Bangkok After breakfast at the hotel, check out and and proceed to Bangkok. On arrival, check into your hotel. Your day is at leisure for independent activities. Evening is free at leisure. Overnight at hotel in Bangkok. Day 04 : Half Day Bangkok City Tour followed by Gem’s Gallery After breakfast at the hotel. -

Geologic Reconnaissance of the Mineral Deposits of Thailand

Geologic Reconnaissance of the Mineral Deposits of Thailand By GLEN F. BROWN, SAMAN BURAVAS, JUA4CHET CHARALJAVANAPHET, NITIPAT JALICHANDRA, WILLIAM D. JOHNSTON, JR., VIJA SRESTHAPUTRA, and GEORGE C. TAYLOR, JR. GEOLOGIC INVESTIGATIONS OF ASIA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 984 Prepared in cooperation with The Royal Thai Department of Mines, under the auspices of the Technical Cooperation Administration of the United States Department of State UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1951 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Oscar L. Chapman, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price $2.50 (paper) CONTENTS Pago Abstract_ ___________________________________^__.____ _._._____.__ 1 Introduction, by Vija Sresthaputra and William D. Johnston, Jr_-_____- 6 Previous geological investigations-.-____________ _________________ 6 The present investigation.__---__--____-___-__________-__-__.___ 7 Acknowledgments__ _ ___-__---__-_-__----______-______________ 8 Geography, by Vija Sresthapiitra--__---_-__--_---_--________________ 10 Political divisions_____-__---___---_-___--____________________ 10 ]\taps available-___.___________-___._________________________'__ 11 Climate._____________________________________________________ 13 General features.____-_-----__-_--_-__-___---______-___-__- 13 Northern Thailand.-_.._-_.-._._.___.___...___.___._...._. 13 Northeastern Thailand.__-__-_____-__--____--____________-_ 14 Central plain...___________________________________________