Integral Study of the Silk Roads: Roads of Dialogue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Office of the Board of Investment E-Mail:Head

Office of the Board of Investment 555 Vibhavadi-Rangsit Rd., Chatuchak, Bangkok 10900, Thailand Tel. 0 2553 8111 Fax. 0 2553 8315 http://www.boi.go.th E-mail:[email protected] The Investor Information Services Center Press Release No. 123/2560 (A. 66) Monday 18th September 2017 On Monday 18th September 2017 the Board of Investment has approved 27 projects with details as follows: Project Location/ Products/Services Nationalities No. Company Contact (Promotion Activity) of Ownership 1 ADVANTECH CORPORATION (Bangkok) International headquarter Thai (THAILAND) CO., LTD. Huaikwang Subdistrict (7.5) Singaporean Huaikwang District Bangkok 2 MR. ROBERT FILIPOVIC (Phuket) Trade and investment Swedish Kamala Subdistrict support office Katu District (7.7) Phuket 3 MR. TAN KOK HWA (Samut Prakan) International trading center Thai Rajadeva Subdistrict (7.6) Taiwanese Bangplee District Malaysian Samut Prakan Page 1 of 5 Project Location/ Products/Services Nationalities No. Company Contact (Promotion Activity) of Ownership 4 Mr.Weerapong Kittiratanawiwat (Bangkok) International trading center Chinese Pathumwan Subdistrict (7.6) Pathumwan District Bangkok 5 SERTIS COMPANY LIMITED (Bangkok) High Value-Added Software Thai 597/5 Nr. 302 (5.7.3) 3rd Flr. Sukhumvit Rd. Klongtannua Subdistrict Wattana District Bangkok 6 ANTON PAAR (THAILAND) (Bangkok) Trade and investment Austrian CO., LTD. Huaikwang support office Bangkok (7.7) 7 COOEC (THAILAND) CO., LTD. (Chonburi) Fabricated steel structure Chinese Sattahip District e.g. jacket and deck etc. Chonburi and repair of other steel structure (4.14.2) 8 MR. MASAYOSHI OKUNO (Bangkok) International trading center Japanese Bangna Subdistrict (7.6) Singaporean Bangna District Bangkok 9 NEW-TECH CO., LTD. -

Thailand Bangkok-Chonburi Highway Construction Project (2) External Evaluator: Masaru Hirano (Mitsubishi UFJ Research and Consul

Thailand Bangkok-Chonburi Highway Construction Project (2) External Evaluator: Masaru Hirano (Mitsubishi UFJ Research and Consulting) Field Survey: January 2006 1. Project Profile and Japan’s ODA Loan ミャンマー ラオス Myanmar Laos タイ Bangkok バンコク カンボジアCambodia Chonburiチョンブリ プロジェクトサイトProject site Map of project area: Bangkok-Chon Buri, Bangkok-Chon Buri Expressway Thailand 1.1 Background In the Sixth Five-Year National Economic and Social Development Plan (1987-1991), the Thai Government specified promotion of the Eastern Seaboard Development Plan as a priority project constituting a key element in the development of the country’s industrial base. This plan sought the development of the eastern coastal area extending over the three provinces of Chon Buri, Rayong, and Chachoengsao (a 80-200km zone in Bangkok’s southeastern district) as Thailand’s No. 2 industrial belt next to Bangkok with a view to developing export industries and correcting regional disparities, thereby decentralizing economic functions that would contribute to ease over-concentrated situation in the Bangkok Metropolitan Area. In response to this decision, the Ministry of Transport, Department of Highways (DOH) established the Sixth Five-Year Highway Development Plan (1987-1991), in which development of a highway network to support the development of the eastern coastal area was positioned as a top-priority project. To achieve this priority objective, the DOH planned construction of the following three routes: expansion of the highway for transport of goods and materials between Bangkok and the eastern coastal area 1 (projects (1) and (2) below), and construction of a highway linking Thailand’s inland northeastern districts to the coastal area, bypassing highly congested Bangkok (project (3) below). -

Gulfofthailand

Ban Sa Khok Pip Wang Lam 348 BANGKOK Khoi Talu Pra 3076 304 chi Sa Kaew Minburi 304 319 n 3200 bur Watthana Ang Sila Non Mak Mun Ratchasan Phanom Nakhon Lat Krabang Sarakham i Huay Jot g Sai Yoi 33 on 317 C A M B O D I A k Aranya Prathet Chachoengsao Pa 304 Kha Pa Khao Chakan SAMUT Bang Sanam Chai Poipet Khet Ngam 3395 PRAKAN Ban Pho Khlong 314 Sai Diaw Non Sao-Eh Plaeng Yao Sisophon e Nam a Si Muang Boran M 315 Yot (Ancient City) 331 CHACHOENGSAO Khlong Hat 3 Phanat Nikhom Khao Takrup Chum Num (660m) Wang Mai Prok Fa Chonburi 3395 344 Nong Samet Ban Bung 317 Ao Krung Thep Bo Thong Khao Yai (Bay of Bangkok) (777m) Khao Daeng CHONBURI Thun Ko Si Khanan Chang Si Racha Lum Borai Nong Yai 3 Laem Chabang Map Yang CHANTHABURI Tamun Battambang 344 Khao Soi Dao Nua Ko (1566m) Phai Pung Ngon Khao Chamao Nong Chek Soi Wang (1024m) Takra Ban Pakard Pattaya g n Chang Khao Chamao/ Nong Pong Nam Psar Pruhm Ko Lan Samet Khao Wong Khao Khitchakut Ron 3191 RAYONG National Park 331 36 Rayo National Park Pailin Si Yaek Ao Ban Sare 317 Ban Klaeng Kong Din 3 Chang Khlong 3 3 Nong Khla Ko Kham Laem Mae Yai Rayong Sattahip Phim Makham U-Taphao 3 Ban Pa-Ah Airfield Ko Ban Phe Ko Man Nai Tha Mai Chanthaburi Chang Thun Samae Saket Ko Thalu Nong Ko Samaesan Ko Samet Nam Tok Phlio Ko Kudee Laem Sadet National Park Sii Ta Chalap 3157 Chak Yai Ko Chuang Khao Laem Ya/ Laem Singh Mu Ko Samet National Park Khlung Pong Dan Chumpon Laem Ko Proet 3159 Tha Chot 3271 TRAT 3156 3 Trat C A M B O D I A Bang Kradan Ban Noen Sung Laem Muang Laem Ngop 318 Ao Trat Tha Sen G U L F O F Ko Chang Laem Sok T H A I L A N D Mu Ko Chang National Marine Park Mai Rut Ko Wai Ko Kradat 0 50 km Ko Rayang Ko Mak 0 30 miles Khlong Yai Ko Mai Si Ko Kut Hat Lek Krong Koh Kong. -

Lions Clubs International

GN1067D Lions Clubs International Clubs Missing a Current Year Club Officer (Only President, Secretary or Treasurer) as of June 30, 2008 District 310 C District Club Club Name Title (Missing) District 310 C 25834 BANGKOK PRAMAHANAKORN President District 310 C 25834 BANGKOK PRAMAHANAKORN Secretary District 310 C 25834 BANGKOK PRAMAHANAKORN Treasurer District 310 C 25837 BANGKOK RATANAKOSIN President District 310 C 25837 BANGKOK RATANAKOSIN Secretary District 310 C 25837 BANGKOK RATANAKOSIN Treasurer District 310 C 25838 CHANTHABURI President District 310 C 25838 CHANTHABURI Secretary District 310 C 25838 CHANTHABURI Treasurer District 310 C 25839 CHA CHEONG SAO President District 310 C 25839 CHA CHEONG SAO Secretary District 310 C 25839 CHA CHEONG SAO Treasurer District 310 C 25843 CHONBURI President District 310 C 25843 CHONBURI Secretary District 310 C 25843 CHONBURI Treasurer District 310 C 25855 PRACHIN-BURI President District 310 C 25855 PRACHIN-BURI Secretary District 310 C 25855 PRACHIN-BURI Treasurer District 310 C 25858 RAYONG President District 310 C 25858 RAYONG Secretary District 310 C 25858 RAYONG Treasurer District 310 C 25859 SAMUTPRAKARN President District 310 C 25859 SAMUTPRAKARN Secretary District 310 C 25859 SAMUTPRAKARN Treasurer District 310 C 25865 TRAD President District 310 C 25865 TRAD Secretary District 310 C 25865 TRAD Treasurer District 310 C 30842 BANGKOK CHAO PRAYA President District 310 C 30842 BANGKOK CHAO PRAYA Secretary District 310 C 30842 BANGKOK CHAO PRAYA Treasurer District 310 C 32840 BANGKOK COSMOPOLITAN -

Logistics Facilities Development in Thailand

July 26, 2016 Press release Daiwa House Industry Co., Ltd. President and COO, Naotake Ohno 3‐3‐5 Umeda, Kita‐ku, Osaka ■Establishment of WHA Daiwa Logistics Property, a joint venture with WHA Corporation Logistics facilities development in Thailand On July 26, 2016, Daiwa House Industry Co., Ltd. (Head office: Osaka City, President: Naotake Ohno) entered into an agreement to establish a joint venture with WHA Corporation PCL (WHA), (Head office: Samutprakarn Province, Thailand, Group CEO: Ms. Jareeporn Jarukornsakul), a leader in Built‐ to‐suit developer of logistics facilities and factories in the Kingdom of Thailand (Thailand). In accordance with this, WHA Daiwa Logistics Property Co., Ltd. is to be founded on July 27, 2016. From July 27, WHA Daiwa Logistics Property will be incorporated to take part in the planning of the Laem Chabang Project and Bang Na Project (Chonlaharnbhichit), which are under development with WHA, and carry out the development, operation, management and leasing of logistics facilities. Additionally, we will combine management resources held by our Group, including the know‐how related to investigations, design, and construction for the development of logistics facilities, and the management and operation of buildings. In line with this, we will make efforts to attract Japanese‐ owned companies and global companies who are looking for logistics facilities overseas. ■Laem Chabang Project Laem Chabang Project (site area: approximately 78,400 m2) is in Laem Chabang District, Chonburi Province approximately 14.7 km from Laem Chabang Deep Seaport, Thailand’s largest trading port. The location encompasses routes for domestic and overseas distribution. A large‐scale industrial park occupies the surrounding area, and numerous major Japanese‐owned companies are planning to set up operations there. -

Bangkok Mitsubishi UFJ Lease & Finance Opens Branch in Chonburi

Mitsubishi UFJ Lease & Finance December 11, 2018 News Release Company Name: Mitsubishi UFJ Lease & Finance Company Limited Representative: Takahiro Yanai, President & CEO Securities Code: 8593 Listing: Tokyo Stock Exchange, First Section Nagoya Stock Exchange, First Section For inquiries: Koichi Kusunoki, General Manager Corporate Communications Department Bangkok Mitsubishi UFJ Lease & Finance Opens Branch in Chonburi Province Mitsubishi UFJ Lease & Finance Company Limited (“MUL”) hereby announces that Bangkok Mitsubishi UFJ Lease Co., Ltd.(“BMUL”), a subsidiary of MUL in Thailand, has opened a branch in Thailand’s Chonburi Province. Chonburi Province is located around 150 kilometers south east of Bangkok, the capital. Chonburi is attracting increasing attention as an industrial center in Thailand’s Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC) development scheme. Chonburi has been designated by the Thai government as a special economic zone in the EEC with special investment incentives, expecting business advancement of next-generation automotive, health care, aviation, and robotics companies. Establishment of the Chonburi branch will strengthen our operation in south east Thailand, and allow us to more speedily respond to the needs of our clients and expand our business in Thailand. <Mitsubishi UFJ Lease & Finance Group’s Thailand business network> *Box with thick outline: New office Company name Address Main businesses Bangkok Mitsubishi UFJ <Head Office> ・Finance lease Lease Co., Ltd. 173/35 Asia Centre Tower, 26th ・Operating lease Floor, South Sathorn Road, ・Auto lease with Maintenance Thungmahamek, Sathorn, Bangkok 10120, Thailand <Chonburi Branch> Harbor Mall, 12th Floor, 4/222 Moo 10, Sukhumvit Road, Tungsukha, Sriracha Chonburi 20230, Thailand MUL (Thailand) Co., Ltd. Same as BMUL Head Office ・Finance lease ・Installment sales ・Sales Finance U-MACHINE Same as BMUL Head Office ・Used Machinery Trading (THAILAND) CO.,LTD. -

Family Gender by Club MBR0018

Summary of Membership Types and Gender by Club Run Date: 9/6/2018 9:01:55AM as of August, 2018 Young Adult Club Fam. Unit Fam. Unit Fam. Unit 1/2 Dues Club Ttl. Club Ttl. Student Student Members Leo Lion Total Total District Number Club Name HH's 1/2 Dues Female Male Females Male Total Female Male Total District 310 C 25834 BANGKOK PRAMAHANAKORN 1 1 1 0 13 24 0 0 0 0 0 37 District 310 C 25837 BANGKOK RATANAKOSIN 0 0 0 0 0 21 0 0 0 0 0 21 District 310 C 25838 CHANTHABURI 0 0 0 0 0 53 0 0 0 0 0 53 District 310 C 25839 CHA CHEONG SAO 0 0 0 0 6 61 0 0 0 0 0 67 District 310 C 25843 CHONBURI 0 0 0 0 2 37 0 0 0 0 0 39 District 310 C 25855 PRACHIN-BURI 0 0 0 0 6 13 0 0 0 0 0 19 District 310 C 25859 SAMUTPRAKARN 0 0 0 0 0 9 0 0 0 0 0 9 District 310 C 25865 TRAD 1 1 1 0 5 31 0 0 0 0 0 36 District 310 C 30842 BANGKOK CHAO PRAYA 14 15 8 7 79 49 0 0 0 0 0 128 District 310 C 32840 BANGKOK COSMOPOLITAN 0 0 0 0 5 15 0 0 0 0 0 20 District 310 C 37497 BANGKOK LAEMTHONG 0 0 0 0 8 22 0 0 0 0 0 30 District 310 C 38719 MUANG KHLUNG L C 0 0 0 0 11 6 0 0 0 0 0 17 District 310 C 39088 BANGKOK BUA LUANG 0 0 0 0 18 42 0 0 0 0 0 60 District 310 C 40175 BANGKOK SUPHANNAHONG 1 1 0 1 10 20 0 0 0 0 0 30 District 310 C 44392 PATTAYA 0 0 0 0 0 22 0 0 0 0 0 22 District 310 C 48192 CHONBURI BANGPLASOI 0 0 0 0 10 37 0 0 0 0 0 47 District 310 C 49951 SAKAEW ARANYAPRATHET 0 0 0 0 17 23 0 0 0 0 0 40 District 310 C 50043 CHONBURI BANGSAEN 0 0 0 0 33 18 0 0 0 0 0 51 District 310 C 50102 CHONBURI PHRATUMNAK PATTAYA 0 0 0 0 40 21 0 0 0 0 0 61 District 310 C 50268 SAMUTPRAKARN SRINAKHARINDRA -

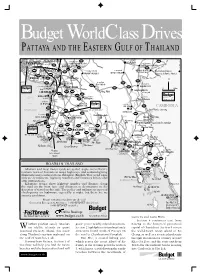

Budgetworldclassdrives

Budget WorldClass Drives PATTAYA AND THE EASTERN GULF OF THAILAND √–·°â« BANG NAM PRIED Õ.æπ¡ “√§“¡ 319 348 PHANOM SARAKHAM SA KAEO Õ.«—≤π“π§√ BANGKOK Õ.∫“ßπÈ”‡ª√’Ȭ« 304 Õ.∫“ߧ≈â“ BANG KHLA WATTHANA NAKHON 3245 33 3121 9 CHACHOENGSAO 304 Õ. π“¡™—¬‡¢µ Õ.‡¢“©°√√®å ARANYAPRATHET International Border Oliver Hargreave ©–‡™‘߇∑√“ 304 KHA0 CHAKAN Õ.Õ√—≠ª√–‡∑» 7 SANAMCHAI KHET Crossing & Border Market 3268 BANG BO Õ.∫â“π‚æ∏‘Ï 34 BAN PHO BANG PHLI Õ.∫“ß∫àÕ PLAENG YAO N Õ.∫“ßæ≈’ Õ.·ª≈߬“« 3395 Õ.æ“π∑Õß ∑à“µ–‡°’¬∫ 3 PHAN THONG 3434 Õ.§≈ÕßÀ“¥ 3259 THA TAKIAP Õ.∫“ߪ–°ß BANG PHANAT NIKHOM 3067 KHLONG HAT PAKONG 3259 0 20km ™≈∫ÿ√’ Õ.æπ— π‘§¡ WANG SOMBUN CHONBURI 349 331 Nong Khok Õ.«—ß ¡∫Ÿ√≥å 344 3245 BANG SAEN 3340 Õ.∫àÕ∑Õß G U L F BAN BUNG ∫.∑ÿàߢπ“π ∫“ß· π Õ.∫â“π∫÷ß 3401 BO THONG Thung Khanan Õ.»√’√“™“ O F SI RACHA Õ.ÀπÕß„À≠à Õ. Õ¬¥“« NONG YAI SOI DAO 3406 C A M B O D I A 3 T H A I L A N D 3138 3245 Tel: (0) 3895 4352 Local border crossing 7 Soi Dao Falls 344 317 Õ.∫“ß≈–¡ÿß 2 Bo Win Õ.ª≈«°·¥ß Khao Chamao Falls BAN LAMUNG PLUAK DAENG Khlong Pong Nam Ron Rafting Ko Lan Krathing 1 Khao Wong PONG NAM RON Local border crossing 3191 WANG CHAN 3377 Õ.‚ªÉßπÈ”√âÕπ Pattaya City 3 36 3471 «—ß®—π∑√å Õ.∫â“π©“ß Õ.∫â“π§à“¬ Õ.·°≈ß Khiritan Dam 3143 KLAENG BAN CHANG BAN KHAI 4 3 3138 3220 Tel: (0) 3871 0717-8 3143 MAKHAM Ko Khram √–¬Õß Õ.¡–¢“¡ Ban Noen RAYONG ®—π∑∫ÿ√’ Tak Daet SATTAHIP 3 Ban Phe Laem Õ.∑à“„À¡à Õ. -

Names, Offices, Telephone and Fax Numbers of Referenced Entities

Annual Report 2011 Other Information 311 REFERENCE INFORMATION KASIKORNBANK PCL conducts commercial banking business, securities business, and other related business under the Financial Institution Business Act, Securities and Exchange Act and other related regulations. Head Office : 1 Soi Rat Burana 27/1, Rat Burana Road, Rat Burana Sub-District, Rat Burana District, Bangkok 10140, Thailand Company Registration Number : 0107536000315 (formerly PCL 105) Telephone : 0 2222 0000 Fax : 0 2470 1144-5 K-Contact Center : 0 2888 8888 (Thai) 0 2888 8888 (English) 0 2800 8888 (Mandarin) Website : www.kasikornbankgroup.com Names, Offices, Telephone and Fax Numbers of Referenced Entities Registrar - Ordinary Shares : Thailand Securities Depository Company Limited The Stock Exchange of Thailand Building, 62 Ratchadaphisek, Klong Toei, Bangkok 10110 Tel. 0 2229 2800 Fax 0 2359 1259 - KASIKORNBANK Subordinated : KASIKORNBANK PUBLIC COMPANY LIMITED Debentures No. 1/2008, due for redemption in 2018 1 Soi Rat Burana 27/1, Rat Burana Road, - KASIKORNBANK Subordinated Rat Burana Sub-District, Rat Burana District, Bangkok 10140 Debentures No. 1/2009, due for redemption in 2019 Tel. 0 2222 0000 - KASIKORNBANK Subordinated Fax 0 2470 1144-5 Debentures No. 1/2010, due for redemption in 2020 - KASIKORNBANK 8 1/4% Subordinated Bonds due 2016 : The Bank of New York Mellon, One Wall Street New York, N.Y. 10286, U.S.A. Tel. (1) 212 495 1784 Fax (1) 212 495 1245 Auditors : Mr. Nirand Lilamethwat, CPA No. 2316 Mr. Winid Silamongkol, CPA No. 3378 Ms. Somboon Supasiripinyo, CPA No. 3731 Ms. Wilai Buranakittisopon, CPA No. 3920 KPMG Phoomchai Audit Limited Empire Tower, 50-51 Floor, 195 South Sathorn Road, Yannawa, Sathorn District, Bangkok 10120 Tel. -

Diversity and Abundance of Phytoplankton in the Ports of Chonburi and Rayong Provinces, the Gulf of Thailand

Ramkhamhaeng International Journal of Science and Technology (2021) 4(2): 1-10 ORIGINAL PAPER Diversity and Abundance of Phytoplankton in the Ports of Chonburi and Rayong Provinces, the Gulf of Thailand Nachaphon Sangmaneea, *, Orathep Mue-sueab, Krissana Komolwanichb, Montaphat Thummasanb, Ploypailin Rangseethampanyab, Makamas Sutthacheepb, Thamasak Yeeminb aGreen Biology Research Division, Research Institute of Green Science and Technology, Shizuoka University, Shizuoka 422-8529, Japan bMarine Biodiversity Research Group, Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Ramkhamhaeng University, Huamark, Bangkok 10240, Thailand *Corresponding author: [email protected] Received: 04 July 2021 / Revised: 29 August 2021 / Accepted: 29 August 2021 Abstract. Phytoplankton are the main component of chain because of their photosynthesis, which food webs in marine and coastal ecosystems and can be serves as the primary food source for various used as a bioindicator to investigate water quality, ecosystem fertility, and ocean circulation, which are also consumers (Waniek & Holliday, 2006). The crucial for the fisheries in Thailand. Phytoplankton abundance and distribution of phytoplankton communities reflect climate variability and changes that vary spatially and locally (Matos et al., 2011). At occur in coastal and marine ecosystems. Here, we aimed the global scale, phytoplankton species diversity to study the diversity and density of phytoplankton in the varied according to environmental variability and Chonburi and Rayong ports. Phytoplankton were collected using a 20-micron mesh size plankton net with different latitudes (Barton et al., 2010). The horizontal hauling from six study sites, including Ao population density and species composition of Udom, Laem Chabang Port, and Ao Bang La Mung in phytoplankton are susceptible to environmental Chonburi Province and the Hin Khong, Hat Nong Fab, changes inducing the changes in water quality and Ko Saket in Rayong Province. -

Report of Thailand on Cartographic Activities During the Period of 2007-2009*

UNITED NATIONS E/CONF.100/CRP.15 ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COUNCIL Eighteenth United Nations Regional Cartographic Conference for Asia and the Pacific Bangkok, 26-29 October 2009 Item 7(a) of the provisional agenda Country Reports Report of Thailand on Cartographic Activities * During the Period of 2007-2009 * Prepared by Thailand Report of Thailand on Cartographic Activities During the Period of 2007-2009 This country report of Thailand presents in brief the cartographic activities during the reporting period 2007-2009 performed by government organizations namely Royal Thai Survey Department , Hydrographic Department and Meteorological Department. The Royal Thai Survey Department (RTSD) The Royal Thai Survey Department is the national mapping organization under the Royal Thai Armed Forces Headquarters , Ministry of Defense. Its responsibilities are to survey and to produce topographic maps of Thailand in support of national security , spatial data infrastructure and other country development projects. The work done during 2007-2009 is summarized as follows. 1. Topographic maps in Thailand Topographic maps in Thailand were initiated in the reign of King Rama the 5th. In 1868, topographic maps covering border area on the west of Thailand were carried out for the purpose of boundary demarcation between Thailand and Burma. Collaboration with western countries, maps covering Bangkok and Thonburi were produced. During 1875, with farsighted thought in country development, King Rama the 5th established Topographic Department serving road construction in Bangkok and set up telecommunication network from Bangkok to Pratabong city. Besides, during this period of time, maps covering Thai gulf were produced serving marine navigation use. In 1881, Mr. Mcarthy from the United Kingdom was appointed as director of Royal Thai Survey Department (RTSD), previously known as Topographic Department, and started conducting Triangulation survey in Thailand. -

A Model of Creative Tourism Management in Coastal Fishery at Ban Bang Lamung, Chonburi Province

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS AND STATISTICS Volume 5, 2017 A Model Of Creative Tourism Management In Coastal Fishery at Ban Bang Lamung, Chonburi Province Dr.Anyapak Prapannetivuth Abstract—The objectives of this research were to study 1) A inspired by the rich culture environment of Southeast Asia. model of creative tourism management in Coastal Fishery at Ban Creative Tourism emphasizes active engagement between Bang Lamung, Chonburi Province 2) To investigate the local guest and host, and supports authentic-active participation. community Participation, Local wisdom about sustainable tourism, The pattern and style of tourism gives an opportunity for the including an obstacles in the potential tourist areas that have been developed to be a model of creative tourism. This research was guests and hosts to exchange their experience and develop qualitative research, the tools was the in-depth interview form. The their creative potential. This leads to understanding the key informant was the 10 specialist of tourism in Ban Bang Lamung, specific cultural of a place. Creative Tourism satisfies the Chonburi Province include a government agency, that is, Designated tourists who prefer more than just “seeing” a different social/ Areas for Sustainable Tourism Administration (Public Organization) cultural environment and wants to “do” and “learn.” Tourists or DASTA. The result found that the Model of Creative Tourism in can get inspiration by practicing a cultural activity rather than Coastal Fishery at Ban Bang Lamung, Chonburi Province is to build or create the value-added for the tourism resources which available just buying some souvenirs and postcards from the shops [2]. in Tourists were especially satisfied with the activity owner In addition, the trend of Creative Economy has also created characteristics, in which all the hosts were ready and willing to new tourism paradigm that differs from the traditional one.