1 Jess Rudolph Shogi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents

Chess E-Magazine Interactive E-Magazine Volume 3 • Issue 1 January/February 2012 Chess Gambits Chess Gambits The Immortal Game Canada and Chess Anderssen- Vs. -Kieseritzky Bill Wall’s Top 10 Chess software programs C Seraphim Press White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents Editorial~ “My Move” 4 contents Feature~ Chess and Canada 5 Article~ Bill Wall’s Top 10 Software Programs 9 INTERACTIVE CONTENT ________________ Feature~ The Incomparable Kasparov 10 • Click on title in Table of Contents Article~ Chess Variants 17 to move directly to Unorthodox Chess Variations page. • Click on “White Feature~ Proof Games 21 Knight Review” on the top of each page to return to ARTICLE~ The Immortal Game 22 Table of Contents. Anderssen Vrs. Kieseritzky • Click on red type to continue to next page ARTICLE~ News Around the World 24 • Click on ads to go to their websites BOOK REVIEW~ Kasparov on Kasparov Pt. 1 25 • Click on email to Pt.One, 1973-1985 open up email program Feature~ Chess Gambits 26 • Click up URLs to go to websites. ANNOTATED GAME~ Bareev Vs. Kasparov 30 COMMENTARY~ “Ask Bill” 31 White Knight Review January/February 2012 White Knight Review January/February 2012 Feature My Move Editorial - Jerry Wall [email protected] Well it has been over a year now since we started this publication. It is not easy putting together a 32 page magazine on chess White Knight every couple of months but it certainly has been rewarding (maybe not so Review much financially but then that really never was Chess E-Magazine the goal). -

Award -...CHESSPROBLEMS.CA

...CHESSPROBLEMS.CA Contents . ISSUE 14 (JULY 2018) 1 Originals 667 2018 Informal Tourney....... 667 Hors Concours............ 673 2 ChessProblems.ca Bulletin TT6 Award 674 3 Articles 678 Arno T¨ungler:Series-mover Artists: Manfred Rittirsch....... 678 Andreas Thoma:¥ Proca variations with e1 and e3...... 681 Jeff Coakley & Andrey Frolkin: Four Rebuses For The Bulletin 684 Arno T¨ungler:Record Breakers VI. 693 Adrian Storisteanu: Lab Notes........... 695 4 Last Page 699 Pauly's Comet............ 699 Editor: Cornel Pacurar Collaborators: Elke Rehder, . Adrian Storisteanu, Arno T¨ungler Originals: [email protected] Articles: [email protected] Correspondence: [email protected] Rook Endgame III ISSN 2292-8324 [Mixed technique on paper, c Elke Rehder, http://www.elke-rehder.de. Reproduced with permission.] ChessProblems.ca Bulletin IIssue 14I ..... ORIGINALS 2018 Informal Tourney T369 T366 T367 T368 Rom´eoBedoni ChessProblems.ca's annual Informal Tourney V´aclavKotˇeˇsovec V´aclavKotˇeˇsovec V´aclavKotˇeˇsovec S´ebastienLuce is open for series-movers of any type and with ¥ any fairy conditions and pieces. Hors concours mp% compositions (any genre) are also welcome! Send to: [email protected]. |£#% 2018 Judge: Manfred Rittirsch (DEU) p4 2018 Tourney Participants: # 1. Alberto Armeni (ITA) 2. Erich Bartel (DEU) C+ (1+5)ser-h#13 C+ (6+2)ser-!=17 C+ (5+2)ser-!=18 C- (1+16)ser-=67 3. Rom´eoBedoni (FRA) No white king Madrasi Madrasi Frankfurt Chess 4. Geoff Foster (AUS) p| p my = Grasshopper = Grasshopper = Nightrider No white king 5. Gunter Jordan (DEU) 4 my % = Leo = Nightrider = Nightriderhopper Royal pawn d6 ´ 6. LuboˇsKekely (SVK) 2 solutions 2 solutions 2 solutions 7. -

2012 Fall Catalog

Green Valley Recreation Fall Course Catalog The Leader in providing recreation, education and social activities! October - December 2012 www.gvrec.org OOverver 4400 NNewew CClasseslasses oofferedffered tthishis ffall!all! RRegistrationegistration bbeginsegins MMonday,onday, SSeptembereptember 1100 1 Dream! Discover! Play! Green Valley Recreation, Inc. GVR Facility Map Board of Directors Social Center Satellite Center 1. Abrego North Rose Theisen - President 1601 N. Abrego Drive N Interstate 19 Joyce Finkelstein - Vice President 2. Abrego South Duval Mine Road Linda Sparks - Secretary 1655 S. Abrego Drive Joyce Bulau - Asst. Secretary 3. Canoa Hills Social Center Erin McGinnis - Treasurer 3660 S. Camino del Sol 1. Abrego John Haggerty - Asst. Treasurer Office - 625-6200 North 4. Casa 5. Casa Jerry Belenker 4. Casa Paloma I Paloma I 9. Las Campanas Paloma II Russ Carpenter 400 W. Circulo del Paladin La Canada Esperanza Chuck Catino 5. Casa Paloma II Abrego Drive 8. East Blvd. Marge Garneau 330 N. Calle del Banderolas Center 625-9909 10. Madera Mark Haskoe Vista Tom Wilsted 6. Continental Vistas 906 W. Camino Guarina 12. West Center 7. Desert Hills Social Center - Executive Director 2980 S. Camino del Sol 6 Continental Office - 625-5221 Vistas 13. Member Lanny Sloan Services Center 8. East Social Center Continental Road 7 S. Abrego Drive Camino del Sol Road East Frontage Road West Frontage Recreation Supervisor Office - 625-4641 Instructional Courses 9. Las Campanas 565 W. Belltower Drive Carolyn Hupp Office - 648-7669 10. Madera Vista 440 S. Camino del Portillo 2. Abrego Catalog Design by: Camino Encanto South 11. Santa Rita Springs 7. Desert Hills Shelly Jackson 921 W. -

CHESS REVIEW but We Can Give a Bit More in a Few 250 West 57Th St Reet , New York 19, N

JULY 1957 CIRCUS TIME (See page 196 ) 50 CENTS ~ scription Rate ONE YEAR $5.50 From the "Amenities and Background of Chess-Play" by Ewart Napier ECHOES FROM THE PAST From Leipsic Con9ress, 1894 An Exhibition Game Almos t formidable opponent was P aul Lipk e in his pr ime, original a nd pi ercing This instruc tive game displays these a nd effective , Quite typica l of 'h is temper classical rivals in holiUay mood, ex is the ",lid Knigh t foray a t 8. Of COU I'se, ploring a dangerous Queen sacrifice. the meek thil'd move of Black des e r\" e~ Played at Augsburg, Germany, i n 1900, m uss ing up ; Pillsbury adopted t he at thirty moves an hOlll" . Tch igorin move, 3 . N- B3. F A L K BEE R COU NT E R GAM BIT Q U EE N' S PAW N GA ME" 0 1'. E. Lasker H. N . Pi llsbury p . Li pke E. Sch iffers ,Vhite Black W hite Black 1 P_K4 P-K4 9 8-'12 B_ KB4 P_Q4 6 P_ KB4 2 P_KB4 P-Q4 10 0-0- 0 B,N 1 P-Q4 8-K2 Mate announred in eight. 2 P- K3 KN_ B3 7 N_ R3 3 P xQP P-K5 11 Q- N4 P_ K B4 0 - 0 8 N_N 5 K N_B3 12 Q-N3 N-Q2 3 B-Q3 P- K 3? P-K R3 4 Q N- B3 p,p 5 Q_ K2 B-Q3 13 8-83 N-B3 4 N-Q2 P-B4 9 P-K R4 6 P_Q3 0-0 14 N-R3 N_ N5 From Leipsic Con9ress. -

Proposal to Encode Heterodox Chess Symbols in the UCS Source: Garth Wallace Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2016-10-25

Title: Proposal to Encode Heterodox Chess Symbols in the UCS Source: Garth Wallace Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2016-10-25 Introduction The UCS contains symbols for the game of chess in the Miscellaneous Symbols block. These are used in figurine notation, a common variation on algebraic notation in which pieces are represented in running text using the same symbols as are found in diagrams. While the symbols already encoded in Unicode are sufficient for use in the orthodox game, they are insufficient for many chess problems and variant games, which make use of extended sets. 1. Fairy chess problems The presentation of chess positions as puzzles to be solved predates the existence of the modern game, dating back to the mansūbāt composed for shatranj, the Muslim predecessor of chess. In modern chess problems, a position is provided along with a stipulation such as “white to move and mate in two”, and the solver is tasked with finding a move (called a “key”) that satisfies the stipulation regardless of a hypothetical opposing player’s moves in response. These solutions are given in the same notation as lines of play in over-the-board games: typically algebraic notation, using abbreviations for the names of pieces, or figurine algebraic notation. Problem composers have not limited themselves to the materials of the conventional game, but have experimented with different board sizes and geometries, altered rules, goals other than checkmate, and different pieces. Problems that diverge from the standard game comprise a genre called “fairy chess”. Thomas Rayner Dawson, known as the “father of fairy chess”, pop- ularized the genre in the early 20th century. -

Kirsch, Gesa E., Ed. Ethics and Representation In

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 400 543 CS 215 516 AUTHOR Mortensen, Peter, Ed.; Kirsch, Gesa E., Ed. TITLE Ethics and Representation in Qualitative Studies of Literacy. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-1596-9 PUB DATE 96 NOTE 347p.; With a collaborative foreword led by Andrea A. Lunsford and an afterword by Ruth E. Ray. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 15969: $21.95 members, $28.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Collected Works General (020) Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC14 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Case Studies; Elementary Secondary Education; *Ethics; *Ethnography; Higher Education; Participant Observation; *Qualitative Research; *Research Methodology; Research Problems; Social Influences; *Writing Research IDENTIFIERS Researcher Role ABSTRACT Reflecting on the practice of qualitative literacy research, this book presents 14 essays that address the most pressing questions faced by qualitative researchers today: how to represent others and themselves in research narratives; how to address ethical dilemmas in research-participant relationi; and how to deal with various rhetorical, institutional, and historical constraints on research. After a foreword ("Considering Research Methods in Composition and Rhetoric" by Andrea A. Lunsford and others) and an introduction ("Reflections on Methodology in Literacy Studies" by the editors), essays in the book are (1) "Seduction and Betrayal in Qualitative Research" (Thomas Newkirk); (2) "Still-Life: Representations and Silences in the. Participant-Observer Role" (Brenda Jo Brueggemann);(3) "Dealing with the Data: Ethical Issues in Case Study Research" (Cheri L. Williams);(4) "'Everything's Negotiable': Collaboration and Conflict in Composition Research" (Russel K. -

YEARBOOK the Information in This Yearbook Is Substantially Correct and Current As of December 31, 2020

OUR HERITAGE 2020 US CHESS YEARBOOK The information in this yearbook is substantially correct and current as of December 31, 2020. For further information check the US Chess website www.uschess.org. To notify US Chess of corrections or updates, please e-mail [email protected]. U.S. CHAMPIONS 2002 Larry Christiansen • 2003 Alexander Shabalov • 2005 Hakaru WESTERN OPEN BECAME THE U.S. OPEN Nakamura • 2006 Alexander Onischuk • 2007 Alexander Shabalov • 1845-57 Charles Stanley • 1857-71 Paul Morphy • 1871-90 George H. 1939 Reuben Fine • 1940 Reuben Fine • 1941 Reuben Fine • 1942 2008 Yury Shulman • 2009 Hikaru Nakamura • 2010 Gata Kamsky • Mackenzie • 1890-91 Jackson Showalter • 1891-94 Samuel Lipchutz • Herman Steiner, Dan Yanofsky • 1943 I.A. Horowitz • 1944 Samuel 2011 Gata Kamsky • 2012 Hikaru Nakamura • 2013 Gata Kamsky • 2014 1894 Jackson Showalter • 1894-95 Albert Hodges • 1895-97 Jackson Reshevsky • 1945 Anthony Santasiere • 1946 Herman Steiner • 1947 Gata Kamsky • 2015 Hikaru Nakamura • 2016 Fabiano Caruana • 2017 Showalter • 1897-06 Harry Nelson Pillsbury • 1906-09 Jackson Isaac Kashdan • 1948 Weaver W. Adams • 1949 Albert Sandrin Jr. • 1950 Wesley So • 2018 Samuel Shankland • 2019 Hikaru Nakamura Showalter • 1909-36 Frank J. Marshall • 1936 Samuel Reshevsky • Arthur Bisguier • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1953 Donald 1938 Samuel Reshevsky • 1940 Samuel Reshevsky • 1942 Samuel 2020 Wesley So Byrne • 1954 Larry Evans, Arturo Pomar • 1955 Nicolas Rossolimo • Reshevsky • 1944 Arnold Denker • 1946 Samuel Reshevsky • 1948 ONLINE: COVID-19 • OCTOBER 2020 1956 Arthur Bisguier, James Sherwin • 1957 • Robert Fischer, Arthur Herman Steiner • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1954 Arthur Bisguier • 1958 E. -

Ancient Chess Turns Moving One Piece in Each Turn

About this Booklet How to Print: This booklet will print best on card stock (110 lb. paper), but can also be printed on regular (20 lb.) paper. Do not print Page 1 (these instructions). First, have your printer print Page 2. Then load that same page back into your printer to be printed on the other side and print Page 3. When you load the page back into your printer, be sure tha t the top and bottom of the pages are oriented correctly. Permissions: You may print this booklet as often as you like, for p ersonal purposes. You may also print this booklet to be included with a game which is sold to another party. You may distribute this booklet, in printed or electronic form freely, not for profit. If this booklet is distributed, it may not be changed in an y way. All copyright and contact information must be kept intact. This booklet may not be sold for profit, except as mentioned a bove, when included in the sale of a board game. To contact the creator of this booklet, please go to the “contact” page at www.AncientChess.com Playing the Game A coin may be tossed to decide who goes first, and the players take Ancient Chess turns moving one piece in each turn. If a player’s King is threatened with capture, “ check” (Persian: “Shah”) is declared, and the player must move so that his King is n o longer threatened. If there is no possible move to relieve the King of the threat, he is in “checkmate” (Persian: “shahmat,” meaning, “the king is at a loss”). -

FESA – Shogi Official Playing Rules

FESA Laws of Shogi FESA Page Federation of European Shogi Associations 1 (12) FESA – Shogi official playing rules The FESA Laws of Shogi cover over-the-board play. This version of the Laws of Shogi was adopted by voting by FESA representatives at August 04, 2017. In these Laws the words `he´, `him’ and `his’ should be taken to mean `she’, `her’ and ‘hers’ as appropriate. PREFACE The FESA Laws of Shogi cannot cover all possible situations that may arise during a game, nor can they regulate all administrative questions. Where cases are not precisely covered by an Article of the Laws, the arbiter should base his decision on analogous situations which are discussed in the Laws, taking into account all considerations of fairness, logic and any special circumstances that may apply. The Laws assume that arbiters have the necessary competence, sound judgement and objectivity. FESA appeals to all shogi players and member federations to accept this view. A member federation is free to introduce more detailed rules for their own events provided these rules: a) do not conflict in any way with the official FESA Laws of Shogi, b) are limited to the territory of the federation in question, and c) are not used for any FESA championship or FESA rating tournament. BASIC RULES OF PLAY Article 1: The nature and objectives of the game of shogi 1.1 The game of shogi is played between two opponents who take turns to make one move each on a rectangular board called a `shogiboard´. The player who starts the game is said to be `sente` or black. -

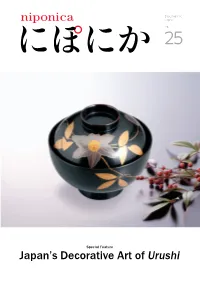

Urushi Selection of Shikki from Various Regions of Japan Clockwise, from Top Left: Set of Vessels for No

Discovering Japan no. 25 Special Feature Japan’s Decorative Art of Urushi Selection of shikki from various regions of Japan Clockwise, from top left: set of vessels for no. pouring and sipping toso (medicinal sake) during New Year celebrations, with Aizu-nuri; 25 stacked boxes for special occasion food items, with Wajima-nuri; tray with Yamanaka-nuri; set of five lidded bowls with Echizen-nuri. Photo: KATSUMI AOSHIMA contents niponica is published in Japanese and six other languages (Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian and Spanish) to introduce to the world the people and culture of Japan today. The title niponica is derived from “Nippon,” the Japanese word for Japan. 04 Special Feature Beauty Created From Strength and Delicacy Japan’s Decorative Art 10 Various Shikki From Different of Urushi Regions 12 Japanese Handicrafts- Craftsmen Who Create Shikki 16 The Japanese Spirit Has Been Inherited - Urushi Restorers 18 Tradition and Innovation- New Forms of the Decorative Art of Urushi Cover: Bowl with Echizen-nuri 20 Photo: KATSUMI AOSHIMA Incorporating Urushi-nuri Into Everyday Life 22 Tasty Japan:Time to Eat! Zoni Special Feature 24 Japan’s Decorative Art of Urushi Strolling Japan Hirosaki Shikki - representative of Japan’s decorative arts. no.25 H-310318 These decorative items of art full of Japanese charm are known as “japan” Published by: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 28 throughout the world. Full of nature's bounty they surpass the boundaries of 2-2-1 Kasumigaseki, Souvenirs of Japan Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-8919, Japan time to encompass everyday life. https://www.mofa.go.jp/ Koshu Inden Beauty Created From Writing box - a box for writing implements. -

World-Mind-Games-Brochure.Pdf

INDEX WHAT ARE THE WORLD MIND GAMES? ............................................ 4 THE SPORTS AND COMPETITION ....................................................... 6 VENUES .................................................................................................... 13 PARTICIPANTS ......................................................................................... 14 OPENING CEREMONY ............................................................................ 15 TV STRATEGY .......................................................................................... 16 MEDIA PROMOTION ................................................................................ 17 CULTURAL PROGRAMME ..................................................................... 18 BENEFITS .................................................................................................. 19 WHAT ARE THE WORLD MIND GAMES? Strategize, Deceive, Challenge The power of the human brain in action Launched in A combination of the world’s Provide 2011 in Beijing, Worldwide China most popular mind sports Exposure Feature the Promote the In cooperation world’s best values of with interna- athletes in strategy, tional sports high-level intelligence and federations competition concentration 4 WORLD MIND GAMES WORLD MIND GAMES 5 SPORTS MIND 5 SPORTS BRIDGE 250+ PLAYERS & OFFICIALS CHESS 150+ players from 37 countries ranked in the top 20 of their DRAUGHTS sport worldwide GO 550+ PARTICIPANTS XIANGQI 15+ DISCIPLINES 25+ CATEGORIES 6 WORLD MIND GAMES COMPETITION -

Read Book Japanese Chess: the Game of Shogi Ebook, Epub

JAPANESE CHESS: THE GAME OF SHOGI PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Trevor Leggett | 128 pages | 01 May 2009 | Tuttle Shokai Inc | 9784805310366 | English | Kanagawa, Japan Japanese Chess: The Game of Shogi PDF Book Memorial Verkouille A collection of 21 amateur shogi matches played in Ghent, Belgium. Retrieved 28 November In particular, the Two Pawn violation is most common illegal move played by professional players. A is the top class. This collection contains seven professional matches. Unlike in other shogi variants, in taikyoku the tengu cannot move orthogonally, and therefore can only reach half of the squares on the board. There are no discussion topics on this book yet. Visit website. The promoted silver. Brian Pagano rated it it was ok Oct 15, Checkmate by Black. Get A Copy. Kai Sanz rated it really liked it May 14, Cross Field Inc. This is a collection of amateur games that were played in the mid 's. The Oza tournament began in , but did not bestow a title until Want to Read Currently Reading Read. This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. White tiger. Shogi players are expected to follow etiquette in addition to rules explicitly described. The promoted lance. Illegal moves are also uncommon in professional games although this may not be true with amateur players especially beginners. Download as PDF Printable version. The Verge. It has not been shown that taikyoku shogi was ever widely played. Thus, the end of the endgame was strategically about trying to keep White's points above the point threshold. You might see something about Gene Davis Software on them, but they probably work.