FESA – Shogi Official Playing Rules

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proposal to Encode Heterodox Chess Symbols in the UCS Source: Garth Wallace Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2016-10-25

Title: Proposal to Encode Heterodox Chess Symbols in the UCS Source: Garth Wallace Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2016-10-25 Introduction The UCS contains symbols for the game of chess in the Miscellaneous Symbols block. These are used in figurine notation, a common variation on algebraic notation in which pieces are represented in running text using the same symbols as are found in diagrams. While the symbols already encoded in Unicode are sufficient for use in the orthodox game, they are insufficient for many chess problems and variant games, which make use of extended sets. 1. Fairy chess problems The presentation of chess positions as puzzles to be solved predates the existence of the modern game, dating back to the mansūbāt composed for shatranj, the Muslim predecessor of chess. In modern chess problems, a position is provided along with a stipulation such as “white to move and mate in two”, and the solver is tasked with finding a move (called a “key”) that satisfies the stipulation regardless of a hypothetical opposing player’s moves in response. These solutions are given in the same notation as lines of play in over-the-board games: typically algebraic notation, using abbreviations for the names of pieces, or figurine algebraic notation. Problem composers have not limited themselves to the materials of the conventional game, but have experimented with different board sizes and geometries, altered rules, goals other than checkmate, and different pieces. Problems that diverge from the standard game comprise a genre called “fairy chess”. Thomas Rayner Dawson, known as the “father of fairy chess”, pop- ularized the genre in the early 20th century. -

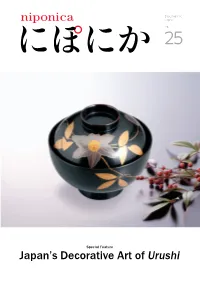

Urushi Selection of Shikki from Various Regions of Japan Clockwise, from Top Left: Set of Vessels for No

Discovering Japan no. 25 Special Feature Japan’s Decorative Art of Urushi Selection of shikki from various regions of Japan Clockwise, from top left: set of vessels for no. pouring and sipping toso (medicinal sake) during New Year celebrations, with Aizu-nuri; 25 stacked boxes for special occasion food items, with Wajima-nuri; tray with Yamanaka-nuri; set of five lidded bowls with Echizen-nuri. Photo: KATSUMI AOSHIMA contents niponica is published in Japanese and six other languages (Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian and Spanish) to introduce to the world the people and culture of Japan today. The title niponica is derived from “Nippon,” the Japanese word for Japan. 04 Special Feature Beauty Created From Strength and Delicacy Japan’s Decorative Art 10 Various Shikki From Different of Urushi Regions 12 Japanese Handicrafts- Craftsmen Who Create Shikki 16 The Japanese Spirit Has Been Inherited - Urushi Restorers 18 Tradition and Innovation- New Forms of the Decorative Art of Urushi Cover: Bowl with Echizen-nuri 20 Photo: KATSUMI AOSHIMA Incorporating Urushi-nuri Into Everyday Life 22 Tasty Japan:Time to Eat! Zoni Special Feature 24 Japan’s Decorative Art of Urushi Strolling Japan Hirosaki Shikki - representative of Japan’s decorative arts. no.25 H-310318 These decorative items of art full of Japanese charm are known as “japan” Published by: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 28 throughout the world. Full of nature's bounty they surpass the boundaries of 2-2-1 Kasumigaseki, Souvenirs of Japan Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-8919, Japan time to encompass everyday life. https://www.mofa.go.jp/ Koshu Inden Beauty Created From Writing box - a box for writing implements. -

1 Jess Rudolph Shogi

Jess Rudolph Shogi – the Chess of Japan Its History and Variants When chess was first invented in India by the end of the sixth century of the current era, probably no one knew just how popular or wide spread the game would become. Only a short time into the second millennium – if not earlier – chess was being played as far as the most distant lands of the known world – the Atlantic coast of Europe and Japan. All though virtually no contact existed for centuries to come between these lands, people from both cultures were playing a game that was very similar; in Europe it was to become the chess most westerners know today and in Japan it was shogi – the Generals Game. Though shogi has many things in common with many other chess variants, those elements are not always clear because of the many differences it also has. Sadly, how the changes came about is not well known since much of the early history of shogi has been lost. In some ways the game is more similar to the Indian chaturanga than its neighboring cousin in China – xiangqi. In other ways, it’s closer to xiangqi than to any other game. In even other ways it has similarities to the Thai chess of makruk. Most likely it has elements from all these lands. It is generally believed that chess came to Japan from China through the trade routs in Korea in more than one wave, the earliest being by the end of tenth century, possibly as early as the eighth. -

World-Mind-Games-Brochure.Pdf

INDEX WHAT ARE THE WORLD MIND GAMES? ............................................ 4 THE SPORTS AND COMPETITION ....................................................... 6 VENUES .................................................................................................... 13 PARTICIPANTS ......................................................................................... 14 OPENING CEREMONY ............................................................................ 15 TV STRATEGY .......................................................................................... 16 MEDIA PROMOTION ................................................................................ 17 CULTURAL PROGRAMME ..................................................................... 18 BENEFITS .................................................................................................. 19 WHAT ARE THE WORLD MIND GAMES? Strategize, Deceive, Challenge The power of the human brain in action Launched in A combination of the world’s Provide 2011 in Beijing, Worldwide China most popular mind sports Exposure Feature the Promote the In cooperation world’s best values of with interna- athletes in strategy, tional sports high-level intelligence and federations competition concentration 4 WORLD MIND GAMES WORLD MIND GAMES 5 SPORTS MIND 5 SPORTS BRIDGE 250+ PLAYERS & OFFICIALS CHESS 150+ players from 37 countries ranked in the top 20 of their DRAUGHTS sport worldwide GO 550+ PARTICIPANTS XIANGQI 15+ DISCIPLINES 25+ CATEGORIES 6 WORLD MIND GAMES COMPETITION -

Read Book Japanese Chess: the Game of Shogi Ebook, Epub

JAPANESE CHESS: THE GAME OF SHOGI PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Trevor Leggett | 128 pages | 01 May 2009 | Tuttle Shokai Inc | 9784805310366 | English | Kanagawa, Japan Japanese Chess: The Game of Shogi PDF Book Memorial Verkouille A collection of 21 amateur shogi matches played in Ghent, Belgium. Retrieved 28 November In particular, the Two Pawn violation is most common illegal move played by professional players. A is the top class. This collection contains seven professional matches. Unlike in other shogi variants, in taikyoku the tengu cannot move orthogonally, and therefore can only reach half of the squares on the board. There are no discussion topics on this book yet. Visit website. The promoted silver. Brian Pagano rated it it was ok Oct 15, Checkmate by Black. Get A Copy. Kai Sanz rated it really liked it May 14, Cross Field Inc. This is a collection of amateur games that were played in the mid 's. The Oza tournament began in , but did not bestow a title until Want to Read Currently Reading Read. This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. White tiger. Shogi players are expected to follow etiquette in addition to rules explicitly described. The promoted lance. Illegal moves are also uncommon in professional games although this may not be true with amateur players especially beginners. Download as PDF Printable version. The Verge. It has not been shown that taikyoku shogi was ever widely played. Thus, the end of the endgame was strategically about trying to keep White's points above the point threshold. You might see something about Gene Davis Software on them, but they probably work. -

Shogi Perfecto EN

• At the end of your turn, in which your unpromoted piece moves into, out of, or within your promotion zone, you may promote it by flipping it over. • If your piece in the promotion zone would no longer be able to move if you don’t Rules of Shogi promote it now, you must promote it. Specifically, this means that a Pawn or a Lance ending its move in the row closest to your opponent must be promoted, as must a Knight in the two rows closest to your opponent. DROP INITIAL SETUP A mochi-goma can be placed in any vacant space on the board as your own piece, Place the pieces as depicted on the 9×9 board. following the rules below: Note that all of the pieces are the same colour. Your pieces point toward your opponent. • It must be placed as its original value (unpromoted). • You cannot drop it in a position where it cannot move. Specifically, this means that a The three rows closest to you are your territory Pawn or a Lance cannot be dropped in the row closest to your opponent, nor can a (and your opponent’s promotion zone). Knight be dropped on the two rows closest to your opponent (see Piece Rules). The three rows closest to your opponent are your • You cannot drop a pawn in front of your opponent’s King in such a way as to give opponent’s territory (and your promotion zone). you checkmate. • You cannot drop a pawn into a column that already has another of your unpromoted pawns. -

Brazchess – Rules V1 3

OLIVEIRA'S BRAZILIAN CHESS OR SIMPLY BRAZCHESS By Rafael R. M. Oliveira (aka Rafael Ramus) - version 1.3 - 2017. Inspired by Chatranj, Modern Chatranj, Makruk, Shogi, Orthochess (FIDE Chess) and the book Encyclopedia of Chess Variants - by D. B. Pritchard. This variant aims to capture some of the elements I enjoy the most in Modern Chatranj, Makruk, Shogi and Modern Chess. I decided to create this chess variant after reading the amazing Encyclopedia of Chess Variants by D. B. Pritchard, even following some of its guidelines. Pieces are less strong than in Modern Chess, but stronger than in Modern Shatranj and Makruk. Some of the "parachuting" that occurs in Shogi is present (regarding the promotion of a pawn GD) and after some thought and playtesting I introduced two elements already present in other Chess variants: a different form of capturing and the concept of passing your turn. What you need to play it: In order to play this variant, you'll need: A) A Modern Chess board (8x8) and pieces (either paint the heads or bases of two pawns from each side, use some other pieces or something to mark 2 pawns from each side); B) 6 different pieces, tokens or even checkers pieces (for the promoted Pawns). C) 1 tokens to represent Passing - you may also want an auxiliary board (the Duchy). Setup: BrazChess is set similarly to regular Chess. Major change is the starting place of Rooks and HPs: Back line: Choose between (White first, then Black): - King (K) in E, Warlord (W) [Golden General/Queen] in D, Rooks (R) [Towers/Chariots] in C and F, Knights (K) in B and G and Hi-Priests (H) [Bishops/Elephants] in A and H; - Alternatively, King (K) in D, Warlord (W) in E. -

Finding Aid to the Sid Sackson Collection, 1867-2003

Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play Sid Sackson Collection Finding Aid to the Sid Sackson Collection, 1867-2003 Summary Information Title: Sid Sackson collection Creator: Sid Sackson (primary) ID: 2016.sackson Date: 1867-2003 (inclusive); 1960-1995 (bulk) Extent: 36 linear feet Language: The materials in this collection are primarily in English. There are some instances of additional languages, including German, French, Dutch, Italian, and Spanish; these are denoted in the Contents List section of this finding aid. Abstract: The Sid Sackson collection is a compilation of diaries, correspondence, notes, game descriptions, and publications created or used by Sid Sackson during his lengthy career in the toy and game industry. The bulk of the materials are from between 1960 and 1995. Repository: Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play at The Strong One Manhattan Square Rochester, New York 14607 585.263.2700 [email protected] Administrative Information Conditions Governing Use: This collection is open to research use by staff of The Strong and by users of its library and archives. Intellectual property rights to the donated materials are held by the Sackson heirs or assignees. Anyone who would like to develop and publish a game using the ideas found in the papers should contact Ms. Dale Friedman (624 Birch Avenue, River Vale, New Jersey, 07675) for permission. Custodial History: The Strong received the Sid Sackson collection in three separate donations: the first (Object ID 106.604) from Dale Friedman, Sid Sackson’s daughter, in May 2006; the second (Object ID 106.1637) from the Association of Game and Puzzle Collectors (AGPC) in August 2006; and the third (Object ID 115.2647) from Phil and Dale Friedman in October 2015. -

Turkish Great Chess and Chinese Whispers: Misadventures of a Chess Variant

TURKISH GREAT CHESS AND CHINESE WHISPERS: MISADVENTURES OF A CHESS VARIANT Georgi Markov National Museum of Natural History – BAS, Sofia Stefan Härtel Freie Universität Berlin A large chess variant with 52 pieces originally described in a 1800s Ottoman Turkish book as šaṭranǧ-i kabīr, or great chess, appears under various names in a number of subsequent Western sources, including authoritative works on chess history and variants. Game rules as presented in the latter are seriously flawed though, with inaccuracies regarding pieces array and moves. Over a period of more than two centuries, baseless assumptions, misreadings of previous sources and outright errors gradually accumulating in the literature have changed the game almost beyond recognition. With some of the game’s aspects not covered even by the original Turkish source, reconstructed rules are suggested and discussed, as well as a reformed variant. Introduction A chess variant with 26 pieces a side was described in a Turkish encyclopaedia, Ad-Durar al-muntahabāt al-manṯūra fī iṣlāḥ al-ġalaṭāt al-mašhūra1 by Abū'r-Rafīd Muḥammad Ḥafīd Ibn-Muṣṭafā ʿĀšir, published in AH 1221/CE 1806/72, as šaṭranǧ-i kabīr, or great chess.3 A number of later sources, including seminal works such as e.g. Murray’s History of Chess (Murray 1913), describe the game under varying names. While all 1 Written in Ottoman Turkish, the title of this work and the name of its author have been transcribed in various ways in later sources. Here, we are following the transcription conventions of the Deutsche Morgenländische Gesellschaft. The copy of this rare book used in this paper is from the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. -

VARIANT CHESS 8 Page 97

July-December 1992 VARIANT CHESS 8 page 97 @ Copyright. 1992. rssN 0958-8248 Publisher and Editor G. P. Jelliss 99 Bohemia Road Variant Chess St Leonards on Sea TN37 6RJ (rJ.K.) In this issue: Hexagonal Chess, Modern Courier Chess, Escalation, Games Consultant Solutions, Semi-Pieces, Variants Duy, Indexes, New Editor/Publisher. Malcolm Horne Volume 1 complete (issues 1-8, II2 pages, A4 size, unbound): f10. 10B Windsor Square Exmouth EX8 1JU New Varieties of Hexagonal Chess find that we need 8 pawns on the second rank plus by G. P. Jelliss 5 on the third rank. I prefer to add 2 more so that there are 5 pawns on each colour, and the rooks are Various schemes have been proposed for playing more securely blocked in. There is then one pawn in chess on boards on which the cells are hexagons each file except the edge files. A nm being a line of instead of squares. A brief account can be found in cells perpendicular to the base-line. The Oxford Companion to Chess 1984 where games Now how should the pawns move? If they are to by Siegmund Wellisch I9L2, H.D.Baskerville L929, continue to block the files we must allow them only Wladyslaw Glinski L949 and Anthony Patton L975 to move directly forward. This is a fers move. For are mentioned. To these should be added the variety their capture moves we have choices: the other two by H. E. de Vasa described in Joseph Boyer's forward fers moves, or the two forward wazit NouveoLx, Jeux d'Ecltecs Non Orthodoxes 1954 moves, or both. -

Space-State Complexity of Korean Chess and Chinese Chess Donghwi Park Korea University, Seoul

Space-state complexity of Korean chess and Chinese chess Donghwi Park Korea University, Seoul Abstract This article describes how to calculate exact space-state complexities of Korean chess and Chinese chess. The state-space complexity (a.k.a. search-space complexity) of a game is defined as the number of legal game positions reachable from the initial position of the game.[1][3] The number of exact space-state complexities are not known for most of games. However, we calculated actual space-state complexities of Korean chess and Chinese chess. Key words: Korean chess, Chinese chess, Janggi, Changgi, Xiangqi, Space-state complexity, Game complexity I. Introduction Chinese chess (Xiangqi) is a popular absolute-strategy board game in China. Korean chess (Janggi) is a popular absolute-strategy board game in Korea, which is derived from Chinese chess. They share very similar pieces and boards. The state-space complexity of a game is defined as the number of legal game positions reachable from the initial position of the game.[1] The number of exact space-state complexities are not known for most of games which include Western chess or Japanese chess (Shogi).[4] There are a few exceptions when number of exact space-state complexities are small, such as Dobutsu shogi[5] or Tic-tac-toe[6]. Unlike Western chess or Japanese chess, Korean chess and Chinese chess do not have promotion rule, which enable calculation of the exact state-space complexity possible. II. Chinese chess Chinese chess board has ten ranks and nine files. There is a river between central two ranks. -

A General Reinforcement Learning Algorithm That Masters Chess, Shogi and Go Through Self-Play

A general reinforcement learning algorithm that masters chess, shogi and Go through self-play David Silver,1;2∗ Thomas Hubert,1∗ Julian Schrittwieser,1∗ Ioannis Antonoglou,1;2 Matthew Lai,1 Arthur Guez,1 Marc Lanctot,1 Laurent Sifre,1 Dharshan Kumaran,1;2 Thore Graepel,1;2 Timothy Lillicrap,1 Karen Simonyan,1 Demis Hassabis1 1DeepMind, 6 Pancras Square, London N1C 4AG. 2University College London, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT. ∗These authors contributed equally to this work. Abstract The game of chess is the longest-studied domain in the history of artificial intelligence. The strongest programs are based on a combination of sophisticated search techniques, domain-specific adaptations, and handcrafted evaluation functions that have been refined by human experts over several decades. By contrast, the AlphaGo Zero program recently achieved superhuman performance in the game of Go by reinforcement learning from self- play. In this paper, we generalize this approach into a single AlphaZero algorithm that can achieve superhuman performance in many challenging games. Starting from random play and given no domain knowledge except the game rules, AlphaZero convincingly defeated a world champion program in the games of chess and shogi (Japanese chess) as well as Go. The study of computer chess is as old as computer science itself. Charles Babbage, Alan Turing, Claude Shannon, and John von Neumann devised hardware, algorithms and theory to analyse and play the game of chess. Chess subsequently became a grand challenge task for a generation of artificial intelligence researchers, culminating in high-performance computer chess programs that play at a super-human level (1,2).