Turkish Great Chess and Chinese Whispers: Misadventures of a Chess Variant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bishop and Knight Save the Day: a World Champion's Favorite Studies

Bishop and Knight Save the Day: A World Champion’s Favorite Studies Sergei Tkachenko Bishop and Knight Save the Day: A World Champion’s Favorite Studies Author: Sergei Tkachenko Translated from the Russian by Ilan Rubin Chess editor: Anastasia Travkina Typesetting by Andrei Elkov (www.elkov.ru) © LLC Elk and Ruby Publishing House, 2019. All rights reserved Cover page drawing by Anna Fokina Illustration Studio (www.fox-artwork.com) Follow us on Twitter: @ilan_ruby www.elkandruby.com ISBN 978-5-6040710-9-0 2 THE BISHOP AND THE KNIGHT HAND IN HAND… The bishop and knight pair often make chess players shudder. Why? Because of the tricky checkmate! Mating with a bishop and knight is far from simple. Indeed, there have been cases when famous players were unable to mate their opponent in the allocated 50 moves. One example involved the Kievan master Evsey Poliak. The game ended in a draw after he failed to mate his opponent with bishop, knight and king versus a lone king. After the game, somebody asked him why he didn’t chase the enemy king into a corner that was the same color as his bishop. The disappointed Poliak replied: “I kept trying to chase him but for some reason the king refused to move there!” There was even an old painting that captured this balance of forces! Back in 1793, French artist Remi-Fursy Descarsin painted a doctor playing chess against… the Grim Reaper, no less. And the doctor looks dead pleased, because he’s just mated Death himself with a bishop and knight! 3 Here’s that position from Descarsin’s painting (No. -

CONTENTS Contents

CONTENTS Contents Symbols 5 Preface 6 Introduction 9 1 Glossary of Attacking and Strategic Terms 11 2 Double Attack 23 2.1: Double Attacks with Queens and Rooks 24 2.2: Bishop Forks 31 2.3: Knight Forks 34 2.4: The Í+Ì Connection 44 2.5: Pawn Forks 45 2.6: The Discovered Double Attack 46 2.7: Another Type of Double Attack 53 Exercises 55 Solutions 61 3 The Role of the Pawns 65 3.1: Pawn Promotion 65 3.2: The Far-Advanced Passed Pawn 71 3.3: Connected Passed Pawns 85 3.4: The Pawn-Wedge 89 3.5: Passive Sacrifices 91 3.6: The Kamikaze Pawn 92 Exercises 99 Solutions 103 4 Attacking the Castled Position 106 4.1: Weakness in the Castled Position 106 4.2: Rooks and Files 112 4.3: The Greek Gift 128 4.4: Other Bishop Sacrifices 133 4.5: Panic on the Long Diagonal 143 4.6: The Knight Sacrifice 150 4.7: The Exchange Sacrifice 162 4.8: The Queen Sacrifice 172 Exercises 176 Solutions 181 5 Drawing Combinations 186 5.1: Perpetual Check 186 5.2: Repetition of Position 194 5.3: Stalemate 197 5.4: Fortress and Blockade 202 5.5: Positional Draws 204 Exercises 207 Solutions 210 6 Combined Tactical Themes 213 6.1: Material, Endings, Zugzwang 214 6.2: One Sacrifice after Another 232 6.3: Extraordinary Combinations 242 6.4: A Diabolical Position 257 Exercises 260 Solutions 264 7 Opening Disasters 268 7.1: Open Games 268 7.2: Semi-Open Games 274 7.3: Closed Games 288 8 Tactical Examination 304 Test 1 306 Test 2 308 Test 3 310 Test 4 312 Test 5 314 Test 6 316 Hints 318 Solutions 320 Index of Names 331 Index of Openings 335 THE ROLE OF THE PAWNS 3 The Role of the Pawns Ever since the distant days of the 18th century 3.1: Pawn Promotion (let us call it the time of the French Revolution, or of François-André Danican Philidor) we have known that “pawns are the soul of chess”. -

Games Ancient and Oriental and How to Play Them, Being the Games Of

CO CD CO GAMES ANCIENT AND ORIENTAL AND HOW TO PLAY THEM. BEING THE GAMES OF THE ANCIENT EGYPTIANS THE HIERA GRAMME OF THE GREEKS, THE LUDUS LATKUNCULOKUM OF THE ROMANS AND THE ORIENTAL GAMES OF CHESS, DRAUGHTS, BACKGAMMON AND MAGIC SQUAEES. EDWARD FALKENER. LONDON: LONGMANS, GEEEN AND Co. AND NEW YORK: 15, EAST 16"' STREET. 1892. All rights referred. CONTENTS. I. INTRODUCTION. PAGE, II. THE GAMES OF THE ANCIENT EGYPTIANS. 9 Dr. Birch's Researches on the games of Ancient Egypt III. Queen Hatasu's Draught-board and men, now in the British Museum 22 IV. The of or the of afterwards game Tau, game Robbers ; played and called by the same name, Ludus Latrunculorum, by the Romans - - 37 V. The of Senat still the modern and game ; played by Egyptians, called by them Seega 63 VI. The of Han The of the Bowl 83 game ; game VII. The of the Sacred the Hiera of the Greeks 91 game Way ; Gramme VIII. Tlie game of Atep; still played by Italians, and by them called Mora - 103 CHESS. IX. Chess Notation A new system of - - 116 X. Chaturanga. Indian Chess - 119 Alberuni's description of - 139 XI. Chinese Chess - - - 143 XII. Japanese Chess - - 155 XIII. Burmese Chess - - 177 XIV. Siamese Chess - 191 XV. Turkish Chess - 196 XVI. Tamerlane's Chess - - 197 XVII. Game of the Maharajah and the Sepoys - - 217 XVIII. Double Chess - 225 XIX. Chess Problems - - 229 DRAUGHTS. XX. Draughts .... 235 XX [. Polish Draughts - 236 XXI f. Turkish Draughts ..... 037 XXIII. }\'ci-K'i and Go . The Chinese and Japanese game of Enclosing 239 v. -

The CCI-U a News Chess Collectors International Vol

The CCI-U A News Chess Collectors International Vol. 2009 Issue I IN THIS ISSUE: The Marshall Chess Foundation Proudly presents A presentation and book signing of Bergman Items sold at auction , including Marcel Duchamp, and the Art of Chess. the chess pieces used in the film “The Page 10. Seventh Seal”. Page 2. Internet links of interest to chess collectors. A photo retrospective of the Sixth Western Page 11. Hemisphere CCI meeting held in beautiful Princeton, New Jersey, May 22-24, 2009. Pages 3-6. Get ready and start packing! The Fourteenth Biennial CCI CONGRESS Will Be Held in Reprint of a presentation to the Sixth CAMBRIDGE, England Western Hemisphere CCI meeting on chess 30 JUNE - 4 JULY 2010 variations by Rick Knowlton. Pages 7-9. (Pages 12-13) How to tell the difference between 'old The State Library of Victoria's Chess English bone sets, Rope twist and Collection online and in person. Page 10. Barleycorn' pattern chess sets. By Alan Dewey. Pages 14-16. The Chess Collector can now be found on line at http://chesscollectorsinternational.club.officelive.com The password is: staunton Members are urged to forward their names and latest email address to Floyd Sarisohn at [email protected] , so that they can be promptly updated on all issues of both The Chess Collector and of CCI-USA, as well as for all the latest events that might be of interest to chess collectors around the world. CCI members can look forward with great Bonhams Chess Auction of October 28, 2009. anticipation to the publication of "Chess 184 lots of chess sets, boards, etc were auctioned at Masterpieces" by our "founding father" Dr George Bonhams in London on October 28, 2009. -

Top 10 Checkmate Pa Erns

GM Miguel Illescas and the Internet Chess Club present: Top 10 Checkmate Pa=erns GM Miguel Illescas doesn't need a presentation, but we're talking about one of the most influential chess players in the last decades, especially in Spain, just to put things in the right perspective. Miguel, so far, has won the Spanish national championship of 1995, 1998, 1999, 2001, 2004, 2005, 2007, and 2010. In team competitions, he has represented his country at many Olympiads, from 1986 onwards, and won an individual bronze medal at Turin in 2006. Miguel won international tournaments too, such as Las Palmas 1987 and 1988, Oviedo 1991, Pamplona 1991/92, 2nd at Leon 1992 (after Boris Gulko), 3rd at Chalkidiki 1992 (after Vladimir Kramnik and Joel Lautier), Lisbon Zonal 1993, and 2nd at Wijk aan Zee 1993 (after Anatoly Karpov). He kept winning during the latter part of the nineties, including Linares (MEX) 1994, Linares (ESP) Zonal 1995, Madrid 1996, and Pamplona 1997/98. Some Palmares! The ultimate goal of a chess player is to checkmate the opponent. We know that – especially at the higher level – it's rare to see someone get checkmated over the board, but when it happens, there is a sense of fulfillment that only a checkmate can give. To learn how to checkmate an opponent is not an easy task, though. Checkmating is probably the only phase of the game that can be associated with mathematics. Maths and checkmating have one crucial thing in common: patterns! GM Miguel is not going to show us a long list of checkmate examples: the series intends to teach patterns. -

Issue 16, June 2019 -...CHESSPROBLEMS.CA

...CHESSPROBLEMS.CA Contents 1 Originals 746 . ISSUE 16 (JUNE 2019) 2019 Informal Tourney....... 746 Hors Concours............ 753 2 Articles 755 Andreas Thoma: Five Pendulum Retros with Proca Anticirce.. 755 Jeff Coakley & Andrey Frolkin: Multicoded Rebuses...... 757 Arno T¨ungler:Record Breakers VIII 766 Arno T¨ungler:Pin As Pin Can... 768 Arno T¨ungler: Circe Series Tasks & ChessProblems.ca TT9 ... 770 3 ChessProblems.ca TT10 785 4 Recently Honoured Canadian Compositions 786 5 My Favourite Series-Mover 800 6 Blast from the Past III: Checkmate 1902 805 7 Last Page 808 More Chess in the Sky....... 808 Editor: Cornel Pacurar Collaborators: Elke Rehder, . Adrian Storisteanu, Arno T¨ungler Originals: [email protected] Articles: [email protected] Chess drawing by Elke Rehder, 2017 Correspondence: [email protected] [ c Elke Rehder, http://www.elke-rehder.de. Reproduced with permission.] ISSN 2292-8324 ..... ChessProblems.ca Bulletin IIssue 16I ORIGINALS 2019 Informal Tourney T418 T421 Branko Koludrovi´c T419 T420 Udo Degener ChessProblems.ca's annual Informal Tourney Arno T¨ungler Paul R˘aican Paul R˘aican Mirko Degenkolbe is open for series-movers of any type and with ¥ any fairy conditions and pieces. Hors concours compositions (any genre) are also welcome! ! Send to: [email protected]. " # # ¡ 2019 Judge: Dinu Ioan Nicula (ROU) ¥ # 2019 Tourney Participants: ¥!¢¡¥£ 1. Alberto Armeni (ITA) 2. Rom´eoBedoni (FRA) C+ (2+2)ser-s%36 C+ (2+11)ser-!F97 C+ (8+2)ser-hsF73 C+ (12+8)ser-h#47 3. Udo Degener (DEU) Circe Circe Circe 4. Mirko Degenkolbe (DEU) White Minimummer Leffie 5. Chris J. Feather (GBR) 6. -

UIL Text 111212

UIL Chess Puzzle Solvin g— Fall/Winter District 2016-2017 —Grades 4 and 5 IMPORTANT INSTRUCTIONS: [Test-administrators, please read text in this box aloud.] This is the UIL Chess Puzzle Solving Fall/Winter District Test for grades four and five. There are 20 questions on this test. You have 30 minutes to complete it. All questions are multiple choice. Use the answer sheet to mark your answers. Multiple choice answers pur - posely do not indicate check, checkmate, or e.p. symbols. You will be awarded one point for each correct answer. No deductions will be made for incorrect answers on this test. Finishing early is not rewarded, even to break ties. So use all of your time. Some of the questions may be hard, but all of the puzzles are interesting! Good luck and have fun! If you don’t already know chess notation, reading and referring to the section below on this page will help you. How to read and answer questions on this test Piece Names Each chessman can • To answer the questions on this test, you’ll also be represented need to know how to read chess moves. It’s by a symbol, except for the pawn. simple to do. (Figurine Notation) K King Q • Every square on the board has an “address” Queen R made up of a letter and a number. Rook B Bishop N Knight Pawn a-h (We write the file it’s on.) • To make them easy to read, the questions on this test use the figurine piece symbols on the right, above. -

More About Checkmate

MORE ABOUT CHECKMATE The Queen is the best piece of all for getting checkmate because it is so powerful and controls so many squares on the board. There are very many ways of getting CHECKMATE with a Queen. Let's have a look at some of them, and also some STALEMATE positions you must learn to avoid. You've already seen how a Rook can get CHECKMATE XABCDEFGHY with the help of a King. Put the Black King on the side of the 8-+k+-wQ-+( 7+-+-+-+-' board, the White King two squares away towards the 6-+K+-+-+& middle, and a Rook or a Queen on any safe square on the 5+-+-+-+-% same side of the board as the King will give CHECKMATE. 4-+-+-+-+$ In the first diagram the White Queen checks the Black King 3+-+-+-+-# while the White King, two squares away, stops the Black 2-+-+-+-+" King from escaping to b7, c7 or d7. If you move the Black 1+-+-+-+-! King to d8 it's still CHECKMATE: the Queen stops the Black xabcdefghy King moving to e7. But if you move the Black King to b8 is CHECKMATE! that CHECKMATE? No: the King can escape to a7. We call this sort of CHECKMATE the GUILLOTINE. The Queen comes down like a knife to chop off the Black King's head. But there's another sort of CHECKMATE that you can ABCDEFGH do with a King and Queen. We call this one the KISS OF 8-+k+-+-+( DEATH. Put the Black King on the side of the board, 7+-wQ-+-+-' the White Queen on the next square towards the middle 6-+K+-+-+& and the White King where it defends the Queen and you 5+-+-+-+-% 4-+-+-+-+$ get something like our next diagram. -

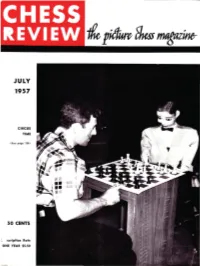

CHESS REVIEW but We Can Give a Bit More in a Few 250 West 57Th St Reet , New York 19, N

JULY 1957 CIRCUS TIME (See page 196 ) 50 CENTS ~ scription Rate ONE YEAR $5.50 From the "Amenities and Background of Chess-Play" by Ewart Napier ECHOES FROM THE PAST From Leipsic Con9ress, 1894 An Exhibition Game Almos t formidable opponent was P aul Lipk e in his pr ime, original a nd pi ercing This instruc tive game displays these a nd effective , Quite typica l of 'h is temper classical rivals in holiUay mood, ex is the ",lid Knigh t foray a t 8. Of COU I'se, ploring a dangerous Queen sacrifice. the meek thil'd move of Black des e r\" e~ Played at Augsburg, Germany, i n 1900, m uss ing up ; Pillsbury adopted t he at thirty moves an hOlll" . Tch igorin move, 3 . N- B3. F A L K BEE R COU NT E R GAM BIT Q U EE N' S PAW N GA ME" 0 1'. E. Lasker H. N . Pi llsbury p . Li pke E. Sch iffers ,Vhite Black W hite Black 1 P_K4 P-K4 9 8-'12 B_ KB4 P_Q4 6 P_ KB4 2 P_KB4 P-Q4 10 0-0- 0 B,N 1 P-Q4 8-K2 Mate announred in eight. 2 P- K3 KN_ B3 7 N_ R3 3 P xQP P-K5 11 Q- N4 P_ K B4 0 - 0 8 N_N 5 K N_B3 12 Q-N3 N-Q2 3 B-Q3 P- K 3? P-K R3 4 Q N- B3 p,p 5 Q_ K2 B-Q3 13 8-83 N-B3 4 N-Q2 P-B4 9 P-K R4 6 P_Q3 0-0 14 N-R3 N_ N5 From Leipsic Con9ress. -

Proposal to Encode Heterodox Chess Symbols in the UCS Source: Garth Wallace Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2016-10-25

Title: Proposal to Encode Heterodox Chess Symbols in the UCS Source: Garth Wallace Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2016-10-25 Introduction The UCS contains symbols for the game of chess in the Miscellaneous Symbols block. These are used in figurine notation, a common variation on algebraic notation in which pieces are represented in running text using the same symbols as are found in diagrams. While the symbols already encoded in Unicode are sufficient for use in the orthodox game, they are insufficient for many chess problems and variant games, which make use of extended sets. 1. Fairy chess problems The presentation of chess positions as puzzles to be solved predates the existence of the modern game, dating back to the mansūbāt composed for shatranj, the Muslim predecessor of chess. In modern chess problems, a position is provided along with a stipulation such as “white to move and mate in two”, and the solver is tasked with finding a move (called a “key”) that satisfies the stipulation regardless of a hypothetical opposing player’s moves in response. These solutions are given in the same notation as lines of play in over-the-board games: typically algebraic notation, using abbreviations for the names of pieces, or figurine algebraic notation. Problem composers have not limited themselves to the materials of the conventional game, but have experimented with different board sizes and geometries, altered rules, goals other than checkmate, and different pieces. Problems that diverge from the standard game comprise a genre called “fairy chess”. Thomas Rayner Dawson, known as the “father of fairy chess”, pop- ularized the genre in the early 20th century. -

PGN/AN Verification for Legal Chess Gameplay

PGN/AN Verification for Legal Chess Gameplay Neil Shah Guru Prashanth [email protected] [email protected] May 10, 2015 Abstract Chess has been widely regarded as one of the world's most popular games through the past several centuries. One of the modern ways in which chess games are recorded for analysis is through the PGN/AN (Portable Game Notation/Algebraic Notation) standard, which enforces a strict set of rules for denoting moves made by each player. In this work, we examine the use of PGN/AN to record and describe moves with the intent of building a system to verify PGN/AN in order to check for validity and legality of chess games. To do so, we formally outline the abstract syntax of PGN/AN movetext and subsequently define denotational state-transition and associated termination semantics of this notation. 1 Introduction Chess is a two-player strategy board game which is played on an eight-by-eight checkered board with 64 squares. There are two players (playing with white and black pieces, respectively), which move in alternating fashion. Each player starts the game with a total of 16 pieces: one king, one queen, two rooks, two knights, two bishops and eight pawns. Each of the pieces moves in a different fashion. The game ends when one player checkmates the opponents' king by placing it under threat of capture, with no defensive moves left playable by the losing player. Games can also end with a player's resignation or mutual stalemate/draw. We examine the particulars of piece movements later in this paper. -

Chess-Training-Guide.Pdf

Q Chess Training Guide K for Teachers and Parents Created by Grandmaster Susan Polgar U.S. Chess Hall of Fame Inductee President and Founder of the Susan Polgar Foundation Director of SPICE (Susan Polgar Institute for Chess Excellence) at Webster University FIDE Senior Chess Trainer 2006 Women’s World Chess Cup Champion Winner of 4 Women’s World Chess Championships The only World Champion in history to win the Triple-Crown (Blitz, Rapid and Classical) 12 Olympic Medals (5 Gold, 4 Silver, 3 Bronze) 3-time US Open Blitz Champion #1 ranked woman player in the United States Ranked #1 in the world at age 15 and in the top 3 for about 25 consecutive years 1st woman in history to qualify for the Men’s World Championship 1st woman in history to earn the Grandmaster title 1st woman in history to coach a Men's Division I team to 7 consecutive Final Four Championships 1st woman in history to coach the #1 ranked Men's Division I team in the nation pnlrqk KQRLNP Get Smart! Play Chess! www.ChessDailyNews.com www.twitter.com/SusanPolgar www.facebook.com/SusanPolgarChess www.instagram.com/SusanPolgarChess www.SusanPolgar.com www.SusanPolgarFoundation.org SPF Chess Training Program for Teachers © Page 1 7/2/2019 Lesson 1 Lesson goals: Excite kids about the fun game of chess Relate the cool history of chess Incorporate chess with education: Learning about India and Persia Incorporate chess with education: Learning about the chess board and its coordinates Who invented chess and why? Talk about India / Persia – connects to Geography Tell the story of “seed”.