PGN/AN Verification for Legal Chess Gameplay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONTENTS Contents

CONTENTS Contents Symbols 5 Preface 6 Introduction 9 1 Glossary of Attacking and Strategic Terms 11 2 Double Attack 23 2.1: Double Attacks with Queens and Rooks 24 2.2: Bishop Forks 31 2.3: Knight Forks 34 2.4: The Í+Ì Connection 44 2.5: Pawn Forks 45 2.6: The Discovered Double Attack 46 2.7: Another Type of Double Attack 53 Exercises 55 Solutions 61 3 The Role of the Pawns 65 3.1: Pawn Promotion 65 3.2: The Far-Advanced Passed Pawn 71 3.3: Connected Passed Pawns 85 3.4: The Pawn-Wedge 89 3.5: Passive Sacrifices 91 3.6: The Kamikaze Pawn 92 Exercises 99 Solutions 103 4 Attacking the Castled Position 106 4.1: Weakness in the Castled Position 106 4.2: Rooks and Files 112 4.3: The Greek Gift 128 4.4: Other Bishop Sacrifices 133 4.5: Panic on the Long Diagonal 143 4.6: The Knight Sacrifice 150 4.7: The Exchange Sacrifice 162 4.8: The Queen Sacrifice 172 Exercises 176 Solutions 181 5 Drawing Combinations 186 5.1: Perpetual Check 186 5.2: Repetition of Position 194 5.3: Stalemate 197 5.4: Fortress and Blockade 202 5.5: Positional Draws 204 Exercises 207 Solutions 210 6 Combined Tactical Themes 213 6.1: Material, Endings, Zugzwang 214 6.2: One Sacrifice after Another 232 6.3: Extraordinary Combinations 242 6.4: A Diabolical Position 257 Exercises 260 Solutions 264 7 Opening Disasters 268 7.1: Open Games 268 7.2: Semi-Open Games 274 7.3: Closed Games 288 8 Tactical Examination 304 Test 1 306 Test 2 308 Test 3 310 Test 4 312 Test 5 314 Test 6 316 Hints 318 Solutions 320 Index of Names 331 Index of Openings 335 THE ROLE OF THE PAWNS 3 The Role of the Pawns Ever since the distant days of the 18th century 3.1: Pawn Promotion (let us call it the time of the French Revolution, or of François-André Danican Philidor) we have known that “pawns are the soul of chess”. -

FIDE Laws of Chess

FIDE Laws of Chess FIDE Laws of Chess cover over-the-board play. The Laws of Chess have two parts: 1. Basic Rules of Play and 2. Competition Rules. The English text is the authentic version of the Laws of Chess (which was adopted at the 84th FIDE Congress at Tallinn (Estonia) coming into force on 1 July 2014. In these Laws the words ‘he’, ‘him’, and ‘his’ shall be considered to include ‘she’ and ‘her’. PREFACE The Laws of Chess cannot cover all possible situations that may arise during a game, nor can they regulate all administrative questions. Where cases are not precisely regulated by an Article of the Laws, it should be possible to reach a correct decision by studying analogous situations which are discussed in the Laws. The Laws assume that arbiters have the necessary competence, sound judgement and absolute objectivity. Too detailed a rule might deprive the arbiter of his freedom of judgement and thus prevent him from finding a solution to a problem dictated by fairness, logic and special factors. FIDE appeals to all chess players and federations to accept this view. A necessary condition for a game to be rated by FIDE is that it shall be played according to the FIDE Laws of Chess. It is recommended that competitive games not rated by FIDE be played according to the FIDE Laws of Chess. Member federations may ask FIDE to give a ruling on matters relating to the Laws of Chess. BASIC RULES OF PLAY Article 1: The nature and objectives of the game of chess 1.1 The game of chess is played between two opponents who move their pieces on a square board called a ‘chessboard’. -

ANALYSIS and IMPLEMENTATION of the GAME ARIMAA Christ-Jan

ANALYSIS AND IMPLEMENTATION OF THE GAME ARIMAA Christ-Jan Cox Master Thesis MICC-IKAT 06-05 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE OF KNOWLEDGE ENGINEERING IN THE FACULTY OF GENERAL SCIENCES OF THE UNIVERSITEIT MAASTRICHT Thesis committee: prof. dr. H.J. van den Herik dr. ir. J.W.H.M. Uiterwijk dr. ir. P.H.M. Spronck dr. ir. H.H.L.M. Donkers Universiteit Maastricht Maastricht ICT Competence Centre Institute for Knowledge and Agent Technology Maastricht, The Netherlands March 2006 II Preface The title of my M.Sc. thesis is Analysis and Implementation of the Game Arimaa. The research was performed at the research institute IKAT (Institute for Knowledge and Agent Technology). The subject of research is the implementation of AI techniques for the rising game Arimaa, a two-player zero-sum board game with perfect information. Arimaa is a challenging game, too complex to be solved with present means. It was developed with the aim of creating a game in which humans can excel, but which is too difficult for computers. I wish to thank various people for helping me to bring this thesis to a good end and to support me during the actual research. First of all, I want to thank my supervisors, Prof. dr. H.J. van den Herik for reading my thesis and commenting on its readability, and my daily advisor dr. ir. J.W.H.M. Uiterwijk, without whom this thesis would not have been reached the current level and the “accompanying” depth. The other committee members are also recognised for their time and effort in reading this thesis. -

Rules of Chess960

Rules of Chess960 A little known and long-discarded offshoot of Classical Chess is the realm of so-called "Randomized Chess" in its various forms. Chess960 stands for Bobby Fischer's new and improved version of "Randomized Chess". Chess960 uses algebraic notation exclusively At the start of every game of a Chess960 game, both players Pawns are set up exactly as they are at the start of every game of Classical Chess. In Chess960, just before the start of every game, both players pieces on their respective back rows receive an identical random shuffle using the Chess960 Computerized Shuffler, which is programmed to set up the pieces in any combination, with the provisos that one Rook has to be to the left and one Rook has to be to the right of the King, and one Bishop has to be on a light- colored square and one Bishop has to be on a dark-colored square. White and Black have identical positions. From behind their respective Pawns the opponents pieces are facing each other directly, symmetrically. Thus for example, if the shuffler places White's back row pieces in the following position: Ra1, Bb1, Kc1, Nd1, Be1, Nf1, Rg1, Qh1, it will place Black's back row Pieces in the following position, Ra8, Bb8, Kc8, Nd8, Be8, Nf8, Rg8, Qh8, etc. (See diagram) In Chess960 there are 960 possible starting positions, the Classical Chess starting position and 959 other starting positions. Of necessity, In Chess960 the castling rule is somewhat modified and broadened to allow for the possibility of each player castling either on or into his or her left side or on or into his or her right side of the board from all of these 960 starting positions. -

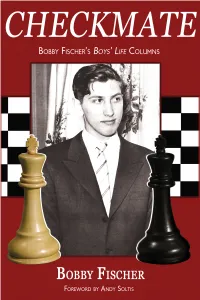

Checkmate Bobby Fischer's Boys' Life Columns

Bobby Fischer’s Boys’ Life Columns Checkmate Bobby Fischer’s Boys’ Life Columns by Bobby Fischer Foreword by Andy Soltis 2016 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 1 Checkmate Bobby Fischer’s Boys’ Life Columns by Bobby Fischer ISBN: 978-1-941270-51-6 (print) ISBN: 978-1-941270-52-3 (eBook) © Copyright 2016 Russell Enterprises, Inc. & Hanon W. Russell All Rights Reserved No part of this book may be used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any manner or form whatsoever or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Chess columns written by Bobby Fischer appeared from December 1966 through January 1970 in the magazine Boys’ Life, published by the Boy Scouts of America. Russell Enterprises, Inc. thanks the Boy Scouts of America for its permission to reprint these columns in this compilation. Published by: Russell Enterprises, Inc. P.O. Box 3131 Milford, CT 06460 USA http://www.russell-enterprises.com [email protected] Editing and proofreading by Peter Kurzdorfer Cover by Janel Lowrance 2 Table of Contents Foreword 4 April 53 by Andy Soltis May 59 From the Publisher 6 Timeline 60 June 61 July 69 Timeline 7 Timeline 70 August 71 1966 September 77 December 9 October 78 November 84 1967 February 11 1969 March 17 February 85 April 19 March 90 Timeline 22 May 23 April 91 June 24 July 31 May 98 Timeline 32 June 99 August 33 July 107 September 37 August 108 Timeline 38 September 115 October 39 October 116 November 46 November 122 December 123 1968 February 47 1970 March 52 January 128 3 Checkmate Foreword Bobby Fischer’s victory over Emil Nikolic at Vinkovci 1968 is one of his most spectacular, perhaps the last great game he played in which he was the bold, go-for-mate sacrificer of his earlier years. -

Starting Out: the Sicilian JOHN EMMS

starting out: the sicilian JOHN EMMS EVERYMAN CHESS Everyman Publishers pic www.everymanbooks.com First published 2002 by Everyman Publishers pIc, formerly Cadogan Books pIc, Gloucester Mansions, 140A Shaftesbury Avenue, London WC2H 8HD Copyright © 2002 John Emms Reprinted 2002 The right of John Emms to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1 857442490 Distributed in North America by The Globe Pequot Press, P.O Box 480, 246 Goose Lane, Guilford, CT 06437·0480. All other sales enquiries should be directed to Everyman Chess, Gloucester Mansions, 140A Shaftesbury Avenue, London WC2H 8HD tel: 020 7539 7600 fax: 020 7379 4060 email: [email protected] website: www.everymanbooks.com EVERYMAN CHESS SERIES (formerly Cadogan Chess) Chief Advisor: Garry Kasparov Commissioning editor: Byron Jacobs Typeset and edited by First Rank Publishing, Brighton Production by Book Production Services Printed and bound in Great Britain by The Cromwell Press Ltd., Trowbridge, Wiltshire Everyman Chess Starting Out Opening Guides: 1857442342 Starting Out: The King's Indian Joe Gallagher 1857442296 -

Pembukaan Catur

Buku Pintar Catur-Pedia Kursus Kilat Teori & Praktik Fienso Suharsono Buku Pintar Catur-Pedia Kursus Kilat Teori & Praktik UU RI No. 19/2002 tentang Hak Cipta Lingkup Hak Cipta Pasal 2: 1. Hak Cipta merupakan hak eksklusif bagi Pencipta atau Pemegang Hak Cipta untuk mengumumkan atau memperbanyak Ciptaannya, yang timbul secara otomatis setelah suatu ciptaan dilahirkan tanpa mengurangi pembatasan menurut peraturan perundang-undangan yang berlaku. Ketentuan Pidana Pasal 72: 1. Barangsiapa dengan sengaja atau tanpa hak melakukan perbuatan sebagaimana dimaksud dalam pasal 2 ayat (1) atau pasal 49 ayat (1) dan ayat (2) dipidana dengan pidana penjara masing-masing paling singkat 1 (satu) bulan dan/atau denda paling sedikit Rp I.000.000,00 (satu juta rupiah), atau pidana penjara paling lama 7 (tujuh) tahun dan/atau denda paling banyak Rp 5.000.000.000,00 (lima milyar rupiah). 2. Barangsiapa dengan sengaja menyiarkan, memamerkan, mengedarkan, atau menjual kepada umum suatu ciptaan atau barang hasil pelanggaran Hak Cipta atau Hak Terkait sebagaimana dimaksud pada ayat (1), dipidana dengan pidana penjara paling lama 5 (lima) tahun dan/atau denda paling banyak Rp 500.000.000,00 (lima ratus juta rupiah). Buku Pintar Catur-Pedia How to Get Rich Kursus Kilat Teori dan Praktik FIENSO SUHARSONO BUKU PINTAR CATUR-PEDIA: KURSUS KILAT TEORI DAN PRAKTIK Fienso Suharsono Copyright © Fienso Suharsono Hak Penerbitan ada pada © 2007 Penerbit ... Hak cipta dilindungi Undang-Undang Penyunting: Tim? Editor: Tim? Tata Letak: Tim? Desain & Ilustrasi Sampul: Tim? Cetakan 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 09 08 07 p. cm. Penerbit ... ISBN 979-XXX-XX-X KDT 1. -

Chess Pieces – Left to Right: King, Rook, Queen, Pawn, Knight and Bishop

CCHHEESSSS by Wikibooks contributors From Wikibooks, the open-content textbooks collection Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled "GNU Free Documentation License". Image licenses are listed in the section entitled "Image Credits." Principal authors: WarrenWilkinson (C) · Dysprosia (C) · Darvian (C) · Tm chk (C) · Bill Alexander (C) Cover: Chess pieces – left to right: king, rook, queen, pawn, knight and bishop. Photo taken by Alan Light. The current version of this Wikibook may be found at: http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Chess Contents Chapter 01: Playing the Game..............................................................................................................4 Chapter 02: Notating the Game..........................................................................................................14 Chapter 03: Tactics.............................................................................................................................19 Chapter 04: Strategy........................................................................................................................... 26 Chapter 05: Basic Openings............................................................................................................... 36 Chapter 06: -

Portable Game Notation Specification and Implementation Guide

11.10.2020 Standard: Portable Game Notation Specification and Implementation Guide Standard: Portable Game Notation Specification and Implementation Guide Authors: Interested readers of the Internet newsgroup rec.games.chess Coordinator: Steven J. Edwards (send comments to [email protected]) Table of Contents Colophon 0: Preface 1: Introduction 2: Chess data representation 2.1: Data interchange incompatibility 2.2: Specification goals 2.3: A sample PGN game 3: Formats: import and export 3.1: Import format allows for manually prepared data 3.2: Export format used for program generated output 3.2.1: Byte equivalence 3.2.2: Archival storage and the newline character 3.2.3: Speed of processing 3.2.4: Reduced export format 4: Lexicographical issues 4.1: Character codes 4.2: Tab characters 4.3: Line lengths 5: Commentary 6: Escape mechanism 7: Tokens 8: Parsing games 8.1: Tag pair section 8.1.1: Seven Tag Roster 8.2: Movetext section 8.2.1: Movetext line justification 8.2.2: Movetext move number indications 8.2.3: Movetext SAN (Standard Algebraic Notation) 8.2.4: Movetext NAG (Numeric Annotation Glyph) 8.2.5: Movetext RAV (Recursive Annotation Variation) 8.2.6: Game Termination Markers 9: Supplemental tag names 9.1: Player related information www.saremba.de/chessgml/standards/pgn/pgn-complete.htm 1/56 11.10.2020 Standard: Portable Game Notation Specification and Implementation Guide 9.1.1: Tags: WhiteTitle, BlackTitle 9.1.2: Tags: WhiteElo, BlackElo 9.1.3: Tags: WhiteUSCF, BlackUSCF 9.1.4: Tags: WhiteNA, BlackNA 9.1.5: Tags: WhiteType, BlackType -

Determining If You Should Use Fritz, Chessbase, Or Both Author: Mark Kaprielian Revised: 2015-04-06

Determining if you should use Fritz, ChessBase, or both Author: Mark Kaprielian Revised: 2015-04-06 Table of Contents I. Overview .................................................................................................................................................. 1 II. Not Discussed .......................................................................................................................................... 1 III. New information since previous versions of this document .................................................................... 1 IV. Chess Engines .......................................................................................................................................... 1 V. Why most ChessBase owners will want to purchase Fritz as well. ......................................................... 2 VI. Comparing the features ............................................................................................................................ 3 VII. Recommendations .................................................................................................................................... 4 VIII. Additional resources ................................................................................................................................ 4 End of Table of Contents I. Overview Fritz and ChessBase are software programs from the same company. Each has a specific focus, but overlap in some functionality. Both programs can be considered specialized interfaces that sit on top a -

Chapter 15, New Pieces

Chapter 15 New pieces (2) : Pieces with limited range [This chapter covers pieces whose range of movement is limited, in the same way that the moves of the king and knight are limited in orthochess.] 15.1 Pieces which can move only one square [The only such piece in orthochess is the king, but the ‘wazir’ (one square orthogonally in any direction), ‘fers’ or ‘firzan’ (one square diagonally in any direction), ‘gold general’ (as wazir and also one square diagonally forward), and ‘silver general’ (as fers and also one square orthogonally forward), have been widely used and will be found in many of the games in the chapters devoted to historical and regional versions of chess. Some other flavours will be found below. In general, games which involve both a one-square mover and ‘something more powerful’ will be found in the section devoted to ‘something more powerful’, but the two later developments of ‘Le Jeu de la Guerre’ are included in this first section for convenience. One-square movers are slow and may seem to be weak, but even the lowly fers can be a potent attacking weapon. ‘Knight for two pawns’ is rarely a good swap, but ‘fers for two pawns’ is a different matter, and a sound tactic, when unobservant defence permits it, is to use the piece with a fers move to smash a hole in the enemy pawn structure so that other men can pour through. In xiangqi (Chinese chess) this piece is confined to a defensive role by the rules of the game, but to restrict it to such a role in other forms of chess may well be a losing strategy.] Le Jeu de la Guerre [M.M.] (‘M.M.’, ranks 1/11, CaHDCuGCaGCuDHCa on ranks perhaps J. -

Endgame Explorations 6: Underpromotion (Part 1) Noam Elkies As Promised in the Previous Installment, We Turn Now to the Theme Of

Endgame Explorations 6: Underpromotion (Part 1) Noam Elkies As promised in the previous installment, we turn now to the theme of under- promotion: upon reaching the far rank a pawn may become a knight, rook or bishop instead of the ordinary queen. Now a knight promotion, while unusual, occurs occasionally in practical play, where it affects the outcome of some basic endgames (such as White Kc7, b6, Black Kc5, Rh6: White draws only by 1 b7 Rh7 2 Kc8 Kc6! 3 b8N!), provides a crucial middlegame check (usually involving a mating attack or a royal fork|for a recent example of the latter see No. II of \What's the Best Move?" on p.52 of the 10/89 Chess Life), and culminates the Lasker Trap in the Albin Counter-Gambit (wherein Black wins only by making a third knight on his seventh turn| see p.24 of the May-June 1989 issue of Chess Horizons). Last year I had the rare occasion for promoting to a knight without check in the middlegame: ¡ ¢ ¢ ¢ ¢ ¢ £ ¢ ¤ ¥ ¦ DIAGRAM1 (Elkies-Soules, after 15.a5) White: Kg1,Qf3,Ra1,Rf1,Bg2,Bf4,Nc3,a5,b2,d4,e5,f2,g3,h3; Black: Ke8,Qd8,Ra8,Rh8,Be7,Nb6,Bd5,a6,b5,c4,c6,e6,f7,g7,h6 This occurred in a casual speed game; so far we had played normally if not accurately, but now Black begins to \complicate": 15 ... Nc3?! 16 Qc6 Qd7? (here I could win a piece with 17 bc3, so 16 ... Kf8 was indicated. But I was distracted by visions of queening:) 17 ab6? Ne2 18 Kh1 Rd8 19 b7 0-0, and here 20 b8Q Qc6 21 Qd8 Qg2 etc.