Developing Chess Talent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dvoretsky Lessons 48

The Instructor The Effects of Replaying I have frequently mentioned, in books and articles, an effective training method: replaying specially selected positions – positions which cannot be “resolved” from beginning to end, so there is really no sense in trying. Instead, players must find, in succession, a series of correct decisions independently (or nearly independently) of each other. In the majority of such exercises, play continues for a minimum of ten moves, although sometimes longer. After all, a shorter variant could in fact be calculated from beginning to end, which would then abolish it as a playing exercise. But The there are sometimes exceptions. The brilliant attack from the following game, which remained hidden in the Instructor annotations, and which is now offered for your consideration, has for some reason never become widely known, although its basic ideas were demonstrated Mark Dvoretsky in Mikhail Botvinnik’s annotations from his book 1941 Match-Tournament. But even those who are familiar with Botvinnik’s analysis will be none the worse for it – for they too will see sharp new variations. Botvinnik - Bondarevsky Leningrad/Moscow 1941 So – you have White. Try to find each move in turn, taking Black’s replies from the following text. Or you might play out this fragment against a friend: he will also find it a problem requiring deep insight into the position. 39.Ne2xd4! In combination with White’s next move, this is a rather obvious exchange: in this way, White gets the opportunity to speculate on the pin along the a1-h8 diagonal. In the game, Botvinnik played the much weaker 39.Ng3?, and after 39...Qe6! 40.Re2 Be3, he ought to have been dead lost: White has neither his pawn, nor any sort of compensation for it. -

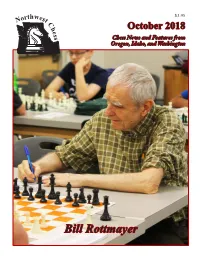

Bill Rottmayer on the Front Cover: Northwest Chess Bill Rottmayer, the Oldest Participant in the Spokane Falls October 2018, Volume 72-10 Issue 849 Open

$3.95 orthwes N t C h October 2018 e s s Chess News and Features from Oregon, Idaho, and Washington Bill Rottmayer On the front cover: Northwest Chess Bill Rottmayer, the oldest participant in the Spokane Falls October 2018, Volume 72-10 Issue 849 Open. Bill has participated in most Spokane Chess Club events the last few years. Photo credit: James Stripes. ISSN Publication 0146-6941 Published monthly by the Northwest Chess Board. On the back cover: POSTMASTER: Send address changes to the Office of Record: Northwest Chess c/o Orlov Chess Academy 4174 148th Ave NE, Dustin Herker at the Las Vegas International Festival where Building I, Suite M, Redmond, WA 98052-5164. he won first place U1000. Photo credit: Nancy Keller. Periodicals Postage Paid at Seattle, WA USPS periodicals postage permit number (0422-390) Chesstoons: NWC Staff Chess cartoons drawn by local artist Brian Berger, Editor: Jeffrey Roland, of West Linn, Oregon. [email protected] Games Editor: Ralph Dubisch, [email protected] Publisher: Duane Polich, Submissions [email protected] Submissions of games (PGN format is preferable for games), Business Manager: Eric Holcomb, stories, photos, art, and other original chess-related content [email protected] are encouraged! Multiple submissions are acceptable; please indicate if material is non-exclusive. All submissions are Board Representatives subject to editing or revision. Send via U.S. Mail to: David Yoshinaga, Josh Sinanan, Jeffrey Roland, NWC Editor Jeffrey Roland, Adam Porth, Chouchanik Airapetian, 1514 S. Longmont Ave. Brian Berger, Duane Polich, Alex Machin, Eric Holcomb. Boise, Idaho 83706-3732 or via e-mail to: Entire contents ©2018 by Northwest Chess. -

ZUGZWANGS in CHESS STUDIES G.Mcc. Haworth,1 H.M.J.F. Van Der

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/290629887 Zugzwangs in Chess Studies Article in ICGA journal · June 2011 DOI: 10.3233/ICG-2011-34205 CITATION READS 1 2,142 3 authors: Guy McCrossan Haworth Harold M.J.F. Van der Heijden University of Reading Gezondheidsdienst voor Dieren 119 PUBLICATIONS 354 CITATIONS 49 PUBLICATIONS 1,232 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Eiko Bleicher 7 PUBLICATIONS 12 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Chess Endgame Analysis View project The Skilloscopy project View project All content following this page was uploaded by Guy McCrossan Haworth on 23 January 2017. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. 82 ICGA Journal June 2011 NOTES ZUGZWANGS IN CHESS STUDIES G.McC. Haworth,1 H.M.J.F. van der Heijden and E. Bleicher Reading, U.K., Deventer, the Netherlands and Berlin, Germany ABSTRACT Van der Heijden’s ENDGAME STUDY DATABASE IV, HHDBIV, is the definitive collection of 76,132 chess studies. The zugzwang position or zug, one in which the side to move would prefer not to, is a frequent theme in the literature of chess studies. In this third data-mining of HHDBIV, we report on the occurrence of sub-7-man zugs there as discovered by the use of CQL and Nalimov endgame tables (EGTs). We also mine those Zugzwang Studies in which a zug more significantly appears in both its White-to-move (wtm) and Black-to-move (btm) forms. We provide some illustrative and extreme examples of zugzwangs in studies. -

11 Triple Loyd

TTHHEE PPUUZZZZLLIINNGG SSIIDDEE OOFF CCHHEESSSS Jeff Coakley TRIPLE LOYDS: BLACK PIECES number 11 September 22, 2012 The “triple loyd” is a puzzle that appears every few weeks on The Puzzling Side of Chess. It is named after Sam Loyd, the American chess composer who published the prototype in 1866. In this column, we feature positions that include black pieces. A triple loyd is three puzzles in one. In each part, your task is to place the black king on the board.to achieve a certain goal. Triple Loyd 07 w________w áKdwdwdwd] àdwdwdwdw] ßwdwdw$wd] ÞdwdRdwdw] Ýwdwdwdwd] Üdwdwdwdw] Ûwdwdpdwd] Údwdwdwdw] wÁÂÃÄÅÆÇÈw Place the black king on the board so that: A. Black is in checkmate. B. Black is in stalemate. C. White has a mate in 1. For triple loyds 1-6 and additional information on Sam Loyd, see columns 1 and 5 in the archives. As you probably noticed from the first puzzle, finding the stalemate (part B) can be easy if Black has any mobile pieces. The black king must be placed to take away their moves. Triple Loyd 08 w________w áwdwdBdwd] àdwdRdwdw] ßwdwdwdwd] Þdwdwdwdw] Ýwdw0Ndwd] ÜdwdPhwdw] ÛwdwGwdwd] Údwdw$wdK] wÁÂÃÄÅÆÇÈw Place the black king on the board so that: A. Black is in checkmate. B. Black is in stalemate. C. White has a mate in 1. The next triple loyd sets a record of sorts. It contains thirty-one pieces. Only the black king is missing. Triple Loyd 09 w________w árhbdwdwH] àgpdpdw0w] ßqdp!w0B0] Þ0ndw0PdN] ÝPdw4Pdwd] ÜdRdPdwdP] Ûw)PdwGPd] ÚdwdwIwdR] wÁÂÃÄÅÆÇÈw Place the black king on the board so that: A. -

2009 U.S. Tournament.Our.Beginnings

Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis Presents the 2009 U.S. Championship Saint Louis, Missouri May 7-17, 2009 History of U.S. Championship “pride and soul of chess,” Paul It has also been a truly national Morphy, was only the fourth true championship. For many years No series of tournaments or chess tournament ever held in the the title tournament was identi- matches enjoys the same rich, world. fied with New York. But it has turbulent history as that of the also been held in towns as small United States Chess Championship. In its first century and a half plus, as South Fallsburg, New York, It is in many ways unique – and, up the United States Championship Mentor, Ohio, and Greenville, to recently, unappreciated. has provided all kinds of entertain- Pennsylvania. ment. It has introduced new In Europe and elsewhere, the idea heroes exactly one hundred years Fans have witnessed of choosing a national champion apart in Paul Morphy (1857) and championship play in Boston, and came slowly. The first Russian Bobby Fischer (1957) and honored Las Vegas, Baltimore and Los championship tournament, for remarkable veterans such as Angeles, Lexington, Kentucky, example, was held in 1889. The Sammy Reshevsky in his late 60s. and El Paso, Texas. The title has Germans did not get around to There have been stunning upsets been decided in sites as varied naming a champion until 1879. (Arnold Denker in 1944 and John as the Sazerac Coffee House in The first official Hungarian champi- Grefe in 1973) and marvelous 1845 to the Cincinnati Literary onship occurred in 1906, and the achievements (Fischer’s winning Club, the Automobile Club of first Dutch, three years later. -

World Stars Sharjah Online International Chess Championship 2020

World Stars Sharjah Online International Chess Championship 2020 World Stars 2020 ● Tournament Book ® Efstratios Grivas 2020 1 Welcome Letter Sharjah Cultural & Chess Club President Sheikh Saud bin Abdulaziz Al Mualla Dear Participants of the World Stars Sharjah Online International Chess Championship 2020, On behalf of the Board of Directors of the Sharjah Cultural & Chess Club and the Organising Committee, I am delighted to welcome all our distinguished participants of the World Stars Sharjah Online International Chess Championship 2020! Unfortunately, due to the recent negative and unpleasant reality of the Corona-Virus, we had to cancel our annual live events in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates. But we still decided to organise some other events online, like the World Stars Sharjah Online International Chess Championship 2020, in cooperation with the prestigious chess platform Internet Chess Club. The Sharjah Cultural & Chess Club was founded on June 1981 with the object of spreading and development of chess as mental and cultural sport across the Sharjah Emirate and in the United Arab Emirates territory in general. As on 2020 we are celebrating the 39th anniversary of our Club I can promise some extra-ordinary events in close cooperation with FIDE, the Asian Chess Federation and the Arab Chess Federation for the coming year 2021, which will mark our 40th anniversary! For the time being we welcome you in our online event and promise that we will do our best to ensure that the World Stars Sharjah Online International Chess Championship -

Weltenfern a Commented Selection of Some of My Works Containing 149 Originals

Weltenfern A commented selection of some of my works containing 149 originals by Siegfried Hornecker Dedicated to the memory of Dan Meinking and Milan Velimirovi ć who both encouraged me to write a book! Weltenfern : German for other-worldly , literally distant from the world , describing a person’s attitude In the opinion of the author the perfect state of mind to compose chess problems. - 1 - Index 1 – Weltenfern 2 – Index 3 – Legal Information 4 – Preface 6 – 20 ideas and themes 6 – Chapter One: A first walk in the park 8 – Chapter Two: Schachstrategie 9 – Chapter Three: An anticipated study 11 – Chapter Four: Sleepless nights, or how pain was turned into beauty 13 – Chapter Five: Knightmares 15 – Chapter Six: Saavedra 17 – Chapter Seven: Volpert, Zatulovskaya and an incredible pawn endgame 21 – Chapter Eight: My home is my castle, but I can’t castle 27 – Intermezzo: Orthodox problems 31 – Chapter Nine: Cooperation 35 – Chapter Ten: Flourish, Knightingale 38 – Chapter Eleven: Endgames 42 – Chapter Twelve: MatPlus 53 – Chapter 13: Problem Paradise and NONA 56 – Chapter 14: Knight Rush 62 – Chapter 15: An idea of symmetry and an Indian mystery 67 – Information: Logic and purity of aim (economy of aim) 72 – Chapter 16: Make the piece go away 77 – Chapter 17: Failure of the attack and the romantic chess as we knew it 82 – Chapter 18: Positional draw (what is it, anyway?) 86 – Chapter 19: Battle for the promotion 91 – Chapter 20: Book Ends 93 – Dessert: Heterodox problems 97 – Appendix: The simple things in life 148 – Epilogue 149 – Thanks 150 – Author index 152 – Bibliography 154 – License - 2 - Legal Information Partial reprint only with permission. -

Award -...CHESSPROBLEMS.CA

...CHESSPROBLEMS.CA Contents . ISSUE 14 (JULY 2018) 1 Originals 667 2018 Informal Tourney....... 667 Hors Concours............ 673 2 ChessProblems.ca Bulletin TT6 Award 674 3 Articles 678 Arno T¨ungler:Series-mover Artists: Manfred Rittirsch....... 678 Andreas Thoma:¥ Proca variations with e1 and e3...... 681 Jeff Coakley & Andrey Frolkin: Four Rebuses For The Bulletin 684 Arno T¨ungler:Record Breakers VI. 693 Adrian Storisteanu: Lab Notes........... 695 4 Last Page 699 Pauly's Comet............ 699 Editor: Cornel Pacurar Collaborators: Elke Rehder, . Adrian Storisteanu, Arno T¨ungler Originals: [email protected] Articles: [email protected] Correspondence: [email protected] Rook Endgame III ISSN 2292-8324 [Mixed technique on paper, c Elke Rehder, http://www.elke-rehder.de. Reproduced with permission.] ChessProblems.ca Bulletin IIssue 14I ..... ORIGINALS 2018 Informal Tourney T369 T366 T367 T368 Rom´eoBedoni ChessProblems.ca's annual Informal Tourney V´aclavKotˇeˇsovec V´aclavKotˇeˇsovec V´aclavKotˇeˇsovec S´ebastienLuce is open for series-movers of any type and with ¥ any fairy conditions and pieces. Hors concours mp% compositions (any genre) are also welcome! Send to: [email protected]. |£#% 2018 Judge: Manfred Rittirsch (DEU) p4 2018 Tourney Participants: # 1. Alberto Armeni (ITA) 2. Erich Bartel (DEU) C+ (1+5)ser-h#13 C+ (6+2)ser-!=17 C+ (5+2)ser-!=18 C- (1+16)ser-=67 3. Rom´eoBedoni (FRA) No white king Madrasi Madrasi Frankfurt Chess 4. Geoff Foster (AUS) p| p my = Grasshopper = Grasshopper = Nightrider No white king 5. Gunter Jordan (DEU) 4 my % = Leo = Nightrider = Nightriderhopper Royal pawn d6 ´ 6. LuboˇsKekely (SVK) 2 solutions 2 solutions 2 solutions 7. -

Fundamental Endings CYRUS LAKDAWALA

First Steps : Fundamental Endings CYRUS LAKDAWALA www.everymanchess.com About the Author Cyrus Lakdawala is an International Master, a former National Open and American Open Cham- pion, and a six-time State Champion. He has been teaching chess for over 30 years, and coaches some of the top junior players in the U.S. Also by the Author: Play the London System A Ferocious Opening Repertoire The Slav: Move by Move 1...d6: Move by Move The Caro-Kann: Move by Move The Four Knights: Move by Move Capablanca: Move by Move The Modern Defence: Move by Move Kramnik: Move by Move The Colle: Move by Move The Scandinavian: Move by Move Botvinnik: Move by Move The Nimzo-Larsen Attack: Move by Move Korchnoi: Move by Move The Alekhine Defence: Move by Move The Trompowsky Attack: Move by Move Carlsen: Move by Move The Classical French: Move by Move Larsen: Move by Move 1...b6: Move by Move Bird’s Opening: Move by Move Petroff Defence: Move by Move Fischer: Move by Move Anti-Sicilians: Move by Move Opening Repertoire ... c6 First Steps: the Modern 3 Contents About the Author 3 Bibliography 5 Introduction 7 1 Essential Knowledge 9 2 Pawn Endings 23 3 Rook Endings 63 4 Queen Endings 119 5 Bishop Endings 144 6 Knight Endings 172 7 Minor Piece Endings 184 8 Rooks and Minor Pieces 206 9 Queen and Other Pieces 243 4 Introduction Why Study Chess at its Cellular Level? A chess battle is no less intense for its lack of brevity. Because my messianic mission in life is to make the chess board a safer place for students and readers, I break the seal of confessional and tell you that some students consider the idea of enjoyable endgame study an oxymoron. -

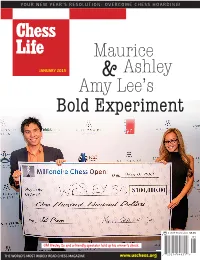

Bold Experiment YOUR NEW YEAR’S RESOLUTION: OVERCOME CHESS HOARDING!

Bold Experiment YOUR NEW YEAR’S RESOLUTION: OVERCOME CHESS HOARDING! Maurice JANUARY 2015 & Ashley Amy Lee’s Bold Experiment FineLine Technologies JN Index 80% 1.5 BWR PU JANUARY A USCF Publication $5.95 01 GM Wesley So and a friendly spectator hold up his winner’s check. 7 25274 64631 9 IFC_Layout 1 12/10/2014 11:28 AM Page 1 SLCC_Layout 1 12/10/2014 11:50 AM Page 1 The Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis is preparing for another fantastic year! 2015 U.S. Championship 2015 U.S. Women’s Championship 2015 U.S. Junior Closed $10K Saint Louis Open GM/IM Title Norm Invitational 2015 Sinquefi eld Cup $10K Thanksgiving Open www.saintlouischessclub.org 4657 Maryland Avenue, Saint Louis, MO 63108 | (314) 361–CHESS (2437) | [email protected] NON-DISCRIMINATION POLICY: The CCSCSL admits students of any race, color, nationality, or ethnic origin. THE UNEXPECTED COLLISION OF CHESS AND HIP HOP CULTURE 2&72%(5r$35,/2015 4652 Maryland Avenue, Saint Louis, MO 63108 (314) 367-WCHF (9243) | worldchesshof.org Photo © Patrick Lanham Financial assistance for this project With support from the has been provided by the Missouri Regional Arts Commission Arts Council, a state agency. CL_01-2014_masthead_JP_r1_chess life 12/10/2014 10:30 AM Page 2 Chess Life EDITORIAL STAFF Chess Life Editor and Daniel Lucas [email protected] Director of Publications Chess Life Online Editor Jennifer Shahade [email protected] Chess Life for Kids Editor Glenn Petersen [email protected] Senior Art Director Frankie Butler [email protected] Editorial Assistant/Copy Editor Alan Kantor [email protected] Editorial Assistant Jo Anne Fatherly [email protected] Editorial Assistant Jennifer Pearson [email protected] Technical Editor Ron Burnett TLA/Advertising Joan DuBois [email protected] USCF STAFF Executive Director Jean Hoffman ext. -

The Old Indian Move by Move

Junior Tay The Old Indian move by move www.everymanchess.com About the Author is a FIDE Candidate Master and an ICCF Senior International Master. He is a for- Junior Tay mer National Rapid Chess Champion and represented Singapore in the 1995 Asian Team Championship. A frequent opening surveys contributor to New in Chess Yearbook, he lives in Balestier, Singapore with his wife, WFM Yip Fong Ling, and their dog, Scottie. He used the Old Indian Defence exclusively against 1 d4 in the 2014 SportsAccord World Mind Games Online event, which he finished in third place out of more than 3000 participants. Also by the Author: The Benko Gambit: Move by Move Ivanchuk: Move by Move Contents About the author 3 Series Foreword 5 Bibliography 6 Introduction 7 1 The Classical Tension Tussle 17 2 Sämisch-Style Set-Ups and Early d4-d5 Systems 139 3 Various Ideas in the Fianchetto System 274 4 Marshalling an Attack with 4 Íg5 and 5 e3 395 5 Navigating the Old Indian Trail: 20 Questions 456 Solutions 467 Index of Variations 490 Index of Games 495 Foreword Move by Move is a series of opening books which uses a question-and-answer format. One of our main aims of the series is to replicate – as much as possible – lessons between chess teachers and students. All the way through, readers will be challenged to answer searching questions and to complete exercises, to test their skills in chess openings and indeed in other key aspects of the game. It’s our firm belief that practising your skills like this is an excellent way to study chess openings, and to study chess in general. -

Opm. Schaakkrant Sep'02

Schaak krant Apeldoorn nummer 3, woensdag 4 september 2002 BIS ambieert topklassering BIS toont ambities. Nu het Apeldoornse schaakteam voor het derde achtereenvolgen- de jaar in de Meesterklasse speelt, is het streven gericht op een eindklassering bij de beste vier van Nederland. BIS is de ‘artiestennaam’ Alexander Kabatianski. waaronder de drie teams Ook Lucien van Beek van Schaakstad Apeldoorn maakt weer deel uit van spelen, die deelnemen aan het team. Nieuwkomer is de landelijke competitie internationaal meester van de KNSB. Vorig jaar Manuel Bosboom. was de naam nog BIS Internationaal meester Rob Beamer Team, maar die Hartoch zal bij thuiswed- naam is ingekort. strijden de publiekstoelich- Afgelopen jaar bereikte ting op partijen verzorgen het team de zesde plaats, en, evenals Erik Knoppert, na in het debuutjaar acht- af en toe invallen. Ook ste te zijn geworden. grootmeester Artur Het basisteam bestaat Joesoepov speelt weer een komend seizoen uit de wedstrijd mee. Apeldoornse spelers Marc Dat BIS een ‘blijvertje’ is Jonker, Merijn van Delft, geworden op het hoogste Harrie de Bie en Freddie schaakniveau, blijkt ook uit van der Elburg. Na vijftien de resultaten in de natio- jaar afwezigheid keert nale beker. Na de tweede Arthur van de plaats in het debuutjaar in Oudeweetering terug uit de Meesterklasse, werd Amstelveen naar afgelopen jaar de derde IM Alexander Kabatianski heeft tweemaal het Apeldoorns Snelschaakkampioenschap in Eetcafé Het Nieuws van Apeldoorn gewonnen. Apeldoorn. Het eerste plaats bereikt. team bestaat verder uit de De speeldata van het team Apeldoorn. Beide hechten organiseert daarom schakers topspelers kun- marktleider is in presenta- grootmeesters Igor Glek staan elders in deze krant sterk aan een goed con- publiekstoelichting bij nen ontmoeten.