Roll to Save Vs. Prejudice: Race in Dungeons & Dragons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Brecht Forum 2/29/12 7:46 AM

Audre Lorde | The Brecht Forum 2/29/12 7:46 AM Home NY Marxist School Programs The Virtual Brecht Economy Watch Support Us Who We Are Search this site: March 26th, 2012 7:30 PM FILM SCREENING/DISCUSSION Co-sponsored by the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation and The Audre Lorde Project Search Audre Lorde The Berlin Years 1984-1992 Tina Campt, Ika Hugel Marshall, Dagmar Schultz DIRECTIONS The Brecht Forum and The Rosa Luxemburg Foundation are proud to sponsor the NY premiere of Audre Lorde: The Berlin Years 1984- RENTAL INFO 1992. We will be joined by director Dagmar Schultz, poet Ika Hugel Marshall and Afro-German scholar, Professor Tina Campt (Barnard College). About the Film: AUDRE LORDE – THE BERLIN YEARS 1984 TO 1992 explores a little-known chapter of the writerʼs prolific life, a period in which she helped ignite the Afro-German Movement and made lasting contributions to the German political and cultural scene before and after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the German reunification. Lorde mentored and encouraged Black German women to write and publish as a way of asserting their identities, rights and culture in a society that isolated and silenced them, while challenging white German women to acknowledge their white privilege. As Lorde wrote in her book Our Dead Behind Us: Poems, “It is not our differences that divide us. It is our inability to recognize, accept, and celebrate those differences.” ;Film director Dagmar Schultz is a writer, director and activist. She is the editor of the groundbreaking text Showing Our Colors: Afro- German Women Speak Out. -

The Aeneid with Rabbits

The Aeneid with Rabbits: Children's Fantasy as Modern Epic by Hannah Parry A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington 2016 Acknowledgements Sincere thanks are owed to Geoff Miles and Harry Ricketts, for their insightful supervision of this thesis. Thanks to Geoff also for his previous supervision of my MA thesis and of the 489 Research Paper which began my academic interest in tracking modern fantasy back to classical epic. He must be thoroughly sick of reading drafts of my writing by now, but has never once showed it, and has always been helpful, enthusiastic and kind. For talking to me about Tolkien, Old English and Old Norse, lending me a whole box of books, and inviting me to spend countless Wednesday evenings at their house with the Norse Reading Group, I would like to thank Christine Franzen and Robert Easting. I'd also like to thank the English department staff and postgraduates of Victoria University of Wellington, for their interest and support throughout, and for being some of the nicest people it has been my privilege to meet. Victoria University of Wellington provided financial support for this thesis through the Victoria University Doctoral Scholarship, for which I am very grateful. For access to letters, notebooks and manuscripts pertaining to Rosemary Sutcliff, Philip Pullman, and C.S. Lewis, I would like to thank the Seven Stories National Centre for Children's Books in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, and Oxford University. Finally, thanks to my parents, William and Lynette Parry, for fostering my love of books, and to my sister, Sarah Parry, for her patience, intelligence, insight, and many terrific conversations about all things literary and fantastical. -

A Symphonic Discussion of the Animal in Richard Adams' Watership Down

Centre for Languages and Literature English Studies A Symphonic Discussion of the Animal in Richard Adams’ Watership Down Elisabeth Kynaston ENGX54 Degree project in English Literature Spring 2020 Centre for Languages and Literature Lund University Supervisor: Cecilia Wadsö-Lecaros Abstract The purpose of this essay is to suggest a new reading of Richard Adams’ Watership Down (1972) by adopting the recently new discipline of Animal Studies. Adams follows a long tradition of talking animals in literature, which still to this day, is an important part of the English literary canon. Throughout this essay, I shall focus on several aspects of the novel. I will look at the anthropomorphized animals and examine how the animals are portrayed in the text. I will seek to offer a structural analysis of Adams’ novel using the structure of the symphony. The essay offers a background discussion of Animal Studies as a theoretical discipline. In addition, the background will provide the reader with a description of how and why the structure of the symphony can function as a method to analyse Adams’ novel. The analysis has been divided into five parts where Jakob von Uexküll’s and Mario Ortiz-Robles’ research will serve as a basis for my discussion as I seek to provide a deeper understanding of how our perception of the animal in literature affects our idea of the animal in our human society. Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. Background 3. First Movement – The Journey 1. Theme One – “Nature/Rabbit” 2. Theme Two – The Human 3. The Rabbit as a Subject 4. -

Sample File 100 Years Have Passed Since Mankind Revolted and Slew the Sorcerer Kings

Sample file 100 years have passed since mankind revolted and slew the Sorcerer Kings. Now, the survivors of five ancient empires begin to rebuild, placing new lives and hopes on the ashes of old. However, even as life continues an ancient and forgotten evil stirs awaiting its moment to strike against mankind. Explore a war-torn land where the struggle for survival continues as new kingdoms arise to impose their will upon the masses. Vicious warlords fight to control territories carved out of the Fallen Empires. Imposing magicians emerge claiming the legacy of the Sorcerer Kings. High Priests of long forgotten gods and goddesses amass wealth in the name of divine right while warrior-monks, devoted to a banished god, patrol the lands bringing justice to people abandoned by their rulers. Tales of the Fallen Empire is a classic Swords and Sorcery setting compatible with the Dungeon Crawl Classics Role Playing Game. Within these pages is a detailed post-apocalyptic fantasySample setting file taking you through an ancient realm that is fighting for its survival and its humanity. Seek your fortune or meet your fate in the burning deserts of the once lush and vibrant land of Vuul, or travel to the humid jungles of Najambi to face the tribes of the Man-Apes and their brutal sacrificial rituals. Within this campaign setting you will find: D 6 new classes: Barbarian, Witch, Draki, Sentinel, Man-Ape, & Marauder D Revised Wizard Class (The Sorcerer) D New Spells D New Creatures D Seafaring and Ritual Magic Rules D A detailed setting inspired by the works of Fritz Lieber, Robert E. -

Alliance Game Distributors Aaw Games Akibabus Alc

GAMES ALLIANCE GAME AKIBABUS ARES GAMES DISTRIBUTORS GAMES BOXITALE: ELITE EXPLORERS An innovative table top game that uses a smartphone/tablet to stream an animated series taking place in a galactic universe. Captain Kadara has a secret THIS WAR OF MINE: TALES FROM mission of investigating the existence of BOXITALE: MINI BOXITALE THE RUINED CITY EXPANSION an unknown space station found on an Boxitale mini assembly adventure game As the siege of Pogoren escalates, its asteroid near Venus. He assembles a uses a smartphone/tablet to stream an citizens must employ new methods of team that includes: Lumi, an I-can- fix- original animated story. The story is survival. Players are forced underground all- technician, a professor and the kids. full of challenges that need to be solved to protect themselves from shelling only to discover that the city sewers have a ART FROM PREVIOUS ISSUE Together, they discover the truth about using Boxitale’s special patent pending the space station and they need to face connectors and rods. Once built, the result lot to offer - both in terms of danger and GAME TRADE MAGAZINE #225 the upcoming challenges that come with is uploaded into the story. Scheduled to opportunities. As if this was not enough, GTM contains articles on gameplay, this new knowledge. The kids use various ship in September 2018. newcomers from the countryside bring previews and reviews, game related crafted technics and a lot of imagination AKB 1300002 ............................$35.00 tales of atrocities as well as supplies fiction, and self contained games and and creativity to solve the challenges from their destroyed homes. -

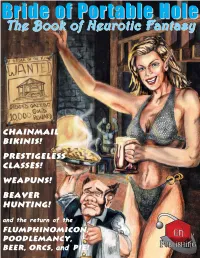

Bride of Portable Hole: the Book of Neurotic Fantasy

BrideBride ofof PorPortabletable HoleHole TThhee BBooookk ooff NNeeuurroottiicc FFaannttaassyy ChainmailChainmail Bikinis!Bikinis! PrestigelessPrestigeless Classes!Classes! WeaPuns!WeaPuns! BeaverBeaver hunting!hunting! and the return of the Flumphinomicon,Flumphinomicon, Poodlemancy,Poodlemancy, BEER,BEER, Orcs,Orcs, andand PIE!PIE! this page intentionally left blank TheThe BookBook ofof NeuroticNeurotic FantasyFantasy CREDITS TABLE OF CONTENTS Written by M Jason Parent & Denise Robinson with d200 Result Chad Barr, Arthur Borko, Leonard “Half-Mad” Briden, Cameron “Fitz” Burns, Matt B Carter, Mike Chapin, Michael 00 Cover Dallaire, Mike “Ralts” Downs, Danny S Dyche, Horacio 01 Credits & Table of Contents Gonzales, Gareth Hanrahan, Brannon Hollingsworth, Neal 02-003 Introductions Levin, Peter Lustig, Joe Mucchiello, Shawn “Zanatose” 04-005 Eric and the Dread Gazebo Muder, Ryan Nock, Hong Ooi, M Jason Parent, Darren 06-442 Prestigeless Classes Pearce, Stefan Pietraszak, Charles Plemons III, Johnathan M. 44-552 Feats Richards, Chris Richardson, Chrystine Robinson, Geneviève 54-778 Encounters Robinson, W. Shade, John Henry Stam, Samuel Terry, Beau 54-60 Return to the Orc & the Pastry Yarbrough, Zjelani 61-66 Revenge of the Orc & the Pastry 67-68 Lost Penguin Colony 69-71 Himover, Poodlemancer 72-75 Elemental Plane of Candy Illustrations by 76-77 Deus Ex Machina Tony ìSquidheadî Monorchio 78-1101 Monsters 78-85 Flumphonomicon with 86-94 Monsters of the Metagame Matthew Cuenca, Johnathan Fuller, J.L.Jones, Kayvan Koie, 95-101 Templates Frank -

FANTASY GAMES and SOCIAL WORLDS Simulation As Leisure

>> Version of Record - Sep 1, 1981 What is This? Downloaded from sag.sagepub.com at SAGE Publications on December 8, 2012 FANTASY GAMES AND SOCIAL WORLDS Simulation as Leisure GARY ALAN FINE University of Minnesota As the longevity and success of this journal attest, simulation games have had a considerable impact on the scholarly commun- ity, spawning cottage industries and academic specialties. Simu- lation gaming is now well established as a legitimate academic pursuit and teaching tool. Simultaneous with the growth of educational games, the 1970s witnessed the development and popularity of other role-playing games, essentially simulations, which have enjoyment and fantasy as their major goals. These games are known generically as fantasy role-playing games. My intent in this article is to describe the games, discuss the relationship of these games to similar activities (including educational simulations), describe the players, and examine their reasons for participating in this social world. By studying these play forms, researchers who specialize in educational simulations can observe parallels in this leisure activity. AUTHOR’S NOTE: The author would like to thank Sherryl Kleinman and Linda Hughes for comments on previous drafts of this article. SIMULATION ~c GAMES, Vol. 12 No. 3, September I981 251-279 @ 1981 Sage Pubhcations, Inc. 251 Downloaded from sag.sagepub.com at SAGE Publications on December 8, 2012 252 WHAT IS FANTASY ROLE-PLAY GAMING? A &dquo;[fantasy] role-playing game&dquo; has been defined as &dquo;any game which allows a number of players to assume the roles of imaginary characters and operate with some degree of freedom in an imaginary environment&dquo; (Lortz, 1979b: 36). -

Tales from the Wood

Tales from The Wood Role playing Game Simon Washbourne CREDITS Initial concept © 2005 by Simon Washbourne & Mark George All rights reserved. Game design, development, editing, & layout Simon Washbourne Artwork Cover: Gill Pearce Interior: Simon Washbourne, Gill Pearce, Helen Roberts & Val Bertin Thanks to all the play testers Annette Washbourne, Nigel Uzzell, Janine Uzzell, Alyson George, Robert Watkins, Rob- ert Irwin, Gary Collett, Leigh Wakefield, Phil Chivers, Phil Ratcliffe and members of Innsworth Wargames and Role Playing United Kingdom (IWARPUK) Recommended Fiction William Horwood; Duncton Wood, Duncton Quest, Duncton Found, Duncton Tales, Duncton Rising, Duncton Stone (moles) Gerry Kilworth; Frost Dancers (hares), Hunters Moon (foxes) A.R. Lloyd; Marshworld, Witchwood, Dragon Pond (weasels) Denys Watkins Pitchford (B.B); Little Grey Men, Down the Bright Stream (gnomes) Chris Freddi; Pork & other tales (several different types of animal) Michael Tod; The Silver Tide, The Second Wave, The Golden Flight (squirrels) Richard Adams; Watership Down (rabbits) Aeron Clement; The Cold Moons (badgers) Brian Carter; Night World (badgers) Colin Dann; The Animals of Farthing Wood, In the Grip of Winter, Fox's Feud, Fox Cub Bold, The Siege of White Deer Park, In the Path of Storm, Battle for the Park, Farthing Wood - The Adventure Begins (several different types of animal) Recommended Non-Fiction Any good natural history books would be highly useful, but these are some of those con- sulted when designing Tales from The Wood. Ron Freethy; Man -

Alternatives to Canadian White Civility Daniel Coleman

Document generated on 09/24/2021 5:27 a.m. International Journal of Canadian Studies Revue internationale d’études canadiennes From Contented Civility to Contending Civilities: Alternatives to Canadian White Civility Daniel Coleman Borders, Migrations and Managing Diversity: New Mappings Frontières, migrations et gestion de la diversité : nouvelles cartographies Number 38, 2008 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/040815ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/040815ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Conseil international d'études canadiennes ISSN 1180-3991 (print) 1923-5291 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Coleman, D. (2008). From Contented Civility to Contending Civilities: Alternatives to Canadian White Civility. International Journal of Canadian Studies / Revue internationale d’études canadiennes, (38), 221–242. https://doi.org/10.7202/040815ar Tous droits réservés © Conseil international d'études canadiennes, 2008 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Daniel Coleman From Contented Civility to Contending Civilities: Alternatives to Canadian White Civility The Author Meets Critics -

Around Paul Gilroy, the Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness

Around The Black Atlantic 1 Around Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness Syllabus / Handbook created by Dr Vanessa Mongey in 2018 Overview This course is constructed around the study of a single seminal secondary text and will students to explore the themes, evidence, approach, argument, literary merit and methodology of said text within the broader context of the historiography that came before and after. By taking the “Atlantic as one single, complex unit of analysis,” Paul Gilroy’s The Black Atlantic will make us travel through the triangle of Africa, Britain and America. This book charts the existence of a counterculture to modernity among black intellectuals, activists, writers, speakers, poets, and artists between approximately the 1850s and the 1980s. The Black Atlantic is outside of national belonging, using examples ranging from slave narratives and novels to jazz and hip-hop. Around The Black Atlantic 2 Gilroy’s ‘Black Atlantic’ delineates a distinctively modern, cultural, and political space that is not specifically African, American, Caribbean, or British, but is, rather, a mix of all of these. This book triggered debates and raised questions of the place of Africa in our historical imagination, transnational history, pan-Africanism, and the relationships of past to present. We will address some combination of: historiography, methodology, theoretical approach(es), concepts (conceived or developed in the book in question), connections/relevance/usefulness to history, and opportunities for comparison with other examples from different periods of world regions, or with other historical works. The students are encouraged to draw comparative or related examples from all the modules they have studied to date, as well as from other sources of information (the media, literature, etc). -

Enrichment Reading (Pdf)

1 Enrichment Reading 2015 Adams, Douglas. The Ultimate Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy. In this collection of novels, Arthur Dent is introduced to the galaxy at large when he is rescued by an alien friend seconds before Earth's destruction and embarks on a series of amazing adventures. Adams, Richard. Watership Down. “Set in England's Downs, a once idyllic rural landscape, this stirring tale of adventure, courage, and survival follows a band of very special creatures on their flight from the intrusion of man and the certain destruction of their home. Led by a stouthearted pair of brothers, they journey forth from their native Sandleford Warren through the harrowing trials posed by predators and adversaries, to a mysterious promised land and a more perfect society.” Alexander, Kwame. The Crossover. Fourteen-year-old twin basketball stars Josh and Jordan wrestle with highs and lows on and off the court as their father ignores his declining health. Austen, Jane. Pride and Prejudice. “One of the most universally loved and admired English novels, Pride and Prejudice was penned as a popular entertainment, but the consummate artistry of Jane Austen (1775–1817) transformed this effervescent tale of rural romance into a witty, shrewdly observed satire of English country life that is now regarded as one of the principal treasures of English language. In a remote Hertfordshire village, far off the good coach roads of George III's England, a country squire of no great means must marry off his five vivacious daughters. At the heart of this all- consuming enterprise are his headstrong second daughter Elizabeth Bennet and her aristocratic suitor Fitzwilliam Darcy — two lovers whose pride must be humbled and prejudices dissolved before the novel can come to its splendid conclusion.” Barrow, Randi. -

Dragon Magazine #100

D RAGON 1 22 45 SPECIAL ATTRACTIONS In the center: SAGA OF OLD CITY Poster Art by Clyde Caldwell, soon to be the cover of an exciting new novel 4 5 THE CITY BEYOND THE GATE Robert Schroeck The longest, and perhaps strongest, AD&D® adventure weve ever done 2 2 At Moonset Blackcat Comes Gary Gygax 34 Gary gives us a glimpse of Gord, with lots more to come Publisher Mike Cook 3 4 DRAGONCHESS Gary Gygax Rules for a fantastic new version of an old game Editor-in-Chief Kim Mohan Editorial staff OTHER FEATURES Patrick Lucien Price Roger Moore 6 Score one for Sabratact Forest Baker Graphics and production Role-playing moves onto the battlefield Roger Raupp Colleen OMalley David C. Sutherland III 9 All about the druid/ranger Frank Mentzer Heres how to get around the alignment problem Subscriptions Georgia Moore 12 Pages from the Mages V Ed Greenwood Advertising Another excursion into Elminsters memory Patricia Campbell Contributing editors 86 The chance of a lifetime Doug Niles Ed Greenwood Reminiscences from the BATTLESYSTEM Supplement designer . Katharine Kerr 96 From first draft to last gasp Michael Dobson This issues contributing artists . followed by the recollections of an out-of-breath editor Dennis Kauth Roger Raupp Jim Roslof 100 Compressor Michael Selinker Marvel Bullpen An appropriate crossword puzzle for our centennial issue Dave Trampier Jeff Marsh Tony Moseley DEPARTMENTS Larry Elmore 3 Letters 101 World Gamers Guide 109 Dragonmirth 10 The forum 102 Convention calendar 110 Snarfquest 69 The ARES Section 107 Wormy COVER Its fitting that an issue filled with things weve never done before should start off with a cover thats unlike any of the ninety-nine that preceded it.