UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michał Krzykawski, Zuzanna Szatanik Gender Studies in French

Michał Krzykawski, Zuzanna Szatanik Gender Studies in French Romanica Silesiana 8/1, 22-30 2013 Mi c h a ł Kr z y K a w s K i , zu z a n n a sz a t a n i K University of Silesia Gender Studies in French They are seen as black therefore they are black; they are seen as women, therefore, they are women. But before being seen that way, they first had to be made that way. Monique WITTIG 12 Within Anglo-American academia, gender studies and feminist theory are recognized to be creditable, fully institutionalized fields of knowledge. In France, however, their standing appears to be considerably lower. One could risk the statement that while in Anglo-American academic world, gender studies have developed into a valid and independent critical theory, the French academe is wary of any discourse that subverts traditional universalism and humanism. A notable example of this suspiciousness is the fact that Judith Butler’s Gen- der Trouble: Feminism and a Subversion of Identity, whose publication in 1990 marked a breakthrough moment for the development of both gender studies and feminist theory, was not translated into French until 2005. On the one hand, therefore, it seems that in this respect not much has changed in French literary studies since 1981, when Jean d’Ormesson welcomed the first woman, Marguerite Yourcenar, to the French Academy with a speech which stressed that the Academy “was not changing with the times, redefining itself in the light of the forces of feminism. Yourcenar just happened to be a woman” (BEASLEY 2, my italics). -

On the Ball! One of the Most Recognizable Stars on the U.S

TVhome The Daily Home June 7 - 13, 2015 On the Ball! One of the most recognizable stars on the U.S. Women’s World Cup roster, Hope Solo tends the goal as the U.S. 000208858R1 Women’s National Team takes on Sweden in the “2015 FIFA Women’s World Cup,” airing Friday at 7 p.m. on FOX. The Future of Banking? We’ve Got A 167 Year Head Start. You can now deposit checks directly from your smartphone by using FNB’s Mobile App for iPhones and Android devices. No more hurrying to the bank; handle your deposits from virtually anywhere with the Mobile Remote Deposit option available in our Mobile App today. (256) 362-2334 | www.fnbtalladega.com Some products or services have a fee or require enrollment and approval. Some restrictions may apply. Please visit your nearest branch for details. 000209980r1 2 THE DAILY HOME / TV HOME Sun., June 7, 2015 — Sat., June 13, 2015 DISH AT&T CABLE DIRECTV CHARTER CHARTER PELL CITY PELL ANNISTON CABLE ONE CABLE TALLADEGA SYLACAUGA SPORTS BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM CONVERSION CABLE COOSA WBRC 6 6 7 7 6 6 6 6 AUTO RACING 5 p.m. ESPN2 2015 NCAA Baseball WBIQ 10 4 10 10 10 10 Championship Super Regionals: Drag Racing Site 7, Game 2 (Live) WCIQ 7 10 4 WVTM 13 13 5 5 13 13 13 13 Sunday Monday WTTO 21 8 9 9 8 21 21 21 8 p.m. ESPN2 Toyota NHRA Sum- 12 p.m. ESPN2 2015 NCAA Baseball WUOA 23 14 6 6 23 23 23 mernationals from Old Bridge Championship Super Regionals Township Race. -

Meine Familie Hatte Es Gut in Auschwitz“ 26 Das Leben Der Lager-SS in Auschwitz-Birkenau Nach Dienstschluss

02/2018 S: I. M. O. N. SHOAH: INTERVENTION. METHODS. DOCUMENTATION. S:I.M.O.N. – Shoah: Intervention. Methods. DocumentatiON. ISSN 2408-9192 Issue 2018/2 DOI: 10.23777/SN.0218 http://doi.org/cztw Board of Editors of VWI’s International Academic Advisory Board: Peter Black/Gustavo Corn/Irina Sherbakova Editors: Éva Kovács/Béla Rásky/Marianne Windsperger Web-Editor: Sandro Fasching Webmaster: Bálint Kovács Layout of PDF: Hans Ljung S:I.M.O.N. is the semi-annual e-journal of the Vienna Wiesenthal Institute for Holocaust Studies (VWI) in English and German. The Vienna Wiesenthal Institute for Holocaust Studies (VWI) is funded by: © 2018 by the Vienna Wiesenthal Institute for Holocaust Studies (VWI), S:I.M.O.N., the authors, and translators, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author(s) and usage right holders. For permission please contact [email protected] S: I. M. O. N. SHOAH: I NTERVENTION. M ETHODS. DOCUMENTATION. TABLE OF CONTENTS ARTICLES Sarah A. Cramsey Jan Masaryk and the Palestinian Solution 4 Solving the German, Jewish, and Statelessness Questions in East Central Europe Anna-Raphaela Schmitz „Meine Familie hatte es gut in Auschwitz“ 26 Das Leben der Lager-SS in Auschwitz-Birkenau nach Dienstschluss Nicola D’Elia Far-Right Parties and the Jews in the 1930s 39 The Antisemitic Turn of Italian Fascism Reconsidered through a Comparison with the French Case SWL-READER Rebecca Jinks Representing Genocide: The Holocaust as Paradigm? 54 CONTEXT: REFUGEES & CITIZENS Michal Frankl Refugees and Citizens. -

Starring Hitler! Adolf Hitler As the Main Character in Twentieth-First Century French Fiction," Studies in 20Th & 21St Century Literature: Vol

Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature Volume 43 Issue 2 Article 44 October 2019 Starring Hitler! Adolf Hitler as the Main Character in Twentieth- First Century French Fiction Marion Duval The College of Wooster, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the French and Francophone Literature Commons, Holocaust and Genocide Studies Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Duval, Marion (2019) "Starring Hitler! Adolf Hitler as the Main Character in Twentieth-First Century French Fiction," Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: Vol. 43: Iss. 2, Article 44. https://doi.org/10.4148/ 2334-4415.2076 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Starring Hitler! Adolf Hitler as the Main Character in Twentieth-First Century French Fiction Abstract Adolf Hitler has remained a prominent figure in popular culture, often portrayed as either the personification of evil or as an object of comedic ridicule. Although Hitler has never belonged solely to history books, testimonials, or documentaries, he has recently received a great deal of attention in French literary fiction. This article reviews three recent French novels by established authors: La part de l’autre (The Alternate Hypothesis) by Emmanuel Schmitt, Lui (Him) by Patrick Besson and La jeunesse mélancolique et très désabusée d’Adolf Hitler (Adolf Hitler’s Depressed and Very Disillusioned Youth) by Michel Folco; all of which belong to the Twenty-First Century French literary trend of focusing on Second World War perpetrators instead of their victims. -

Spanish Through Time

ROMANCE LANGUAGES Rhaeto-Cisalpine at a glance Spanish through Time Vol.1 Phonology, Orthography, FLORA KLEIN-ANDREU Morphology Stony Brook University CLAUDI MENEGHIN MIUR (Ministero dell'Istruzione Università Spanish through time is an introduction to the development of the Spanish language, e ricerca) designed for readers with little or no prior experience in linguistics. It therefore stresses explanation of the workings of language and its development over time: They are viewed as Rhaeto-Cisalpine (or Padanese) is a western attibutable to characteristics of human speakers, in particular social and historical Romance language, spoken in the Po valley (extended to include the Ligurian coast), which circumstances, as illustrated by the history of Spanish. has developed in an independent fashion from The development of Spanish from Latin is presented divided into three broad periods-- Italian and is strictly related to French, Occitan, "Vulgar Latin", Castilian, and Spanish--characterized by specific linguistic developments and Catalan. This subject has been relatively and the historical circumstances in which they occurred. In each case the mechanics of neglected in recent years, apart from a monumental work by Geoffrey Hull, dating back particular language changes are explained in detail, in everyday terms. Emphasis is on the to 1982. more general developments that differentiate, first, various Romance languages, and finally This book aims at both offering a solid different current varieties of Castilian-- Peninsular and Atlantic (American). Evidence is reference about, and at proposing a complete also presented for the chronology of some major changes, so as to familiarize the reader synthesis of this diasystem, including the Rhaeto-Romance languages and the so called with traditional linguistic reasoning. -

World Expo Milano Ggrouproup Traveltravel Toto Italyitaly Sincesince 19851985 Gadis Italia Since 1985

2015 World Expo Milano GGrouproup ttravelravel ttoo IItalytaly ssinceince 11985985 Gadis Italia Since 1985 Travel Ideas 2015 This is the 30th Gadis catalogue. Soon we will be New tours and evergreens celebrating our 3rd decade of business in the Group Incoming industry. Our clients often com- pliment us on how we are just as enthusiastic and New ideas for your travel excursions passionate about what we are doing today, as we were when we started 30 years ago. The best of Italian We feel honoured and even more motivated to Food and wine tradition keep doing our very best to share our knowl- edge and appreciation of Italy: the marvellous, Music related extraordinary, and (at times) complicated coun- Program try that it is. With help from the entire team, we wanted the new catalogue to emphasise fresh Art cities of Italy ideas and newly inspired itineraries for our cli- ents; now more than ever it is important to off er tantalising products that whet tourists’ appetites Active travel for exploration. We believe we are headed in the right direction; especially considering the growing success of our Our favourite hotels suitable for groups specially crafted - sometimes exclusive - itinerar- ies for groups and events. We accompany you on your journey through Italy’s regions with more Selected Events than 200 travel ideas. If you don’t fi nd one that interests you, please do call us: we have plenty more ideas that we haven't yet published! S Travel slowly, enjoy fully lo w Happy reading from your Gadis Team! News, curious facts and useful information -

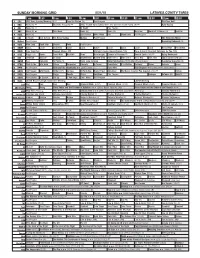

Sunday Morning Grid 5/31/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/31/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å 2015 French Open Tennis Men’s and Women’s Fourth Round. (N) Å Auto Racing 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å World of X Games (N) IndyCar 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program The Simpsons Movie 13 MyNet Paid Program Becoming Redwood (R) 18 KSCI Man Land Rock Star Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Easy Yoga Pain Deepak Chopra MD JJ Virgin’s Sugar Impact Secret (TVG) Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) 28 KCET Raggs Pets. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Echoes of Creation Å Sacred Earth (TVG) Å Aging Backwards 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Taxi › (2004) (PG-13) 34 KMEX Paid Conexión Al Punto (N) Hotel Todo Incluido Duro Pero Seguro (1978) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Alvin and the Chipmunks ›› (2007) Jason Lee. -

Help Languages

Edutasia – Help languages Talk Now help languages ▪ Abruzzese ▪ Hausa ▪ Punjabi (Indian) ▪ Afrikaans ▪ Hawaiian ▪ Quechua ▪ Albanian ▪ Hebrew ▪ Romanian ▪ Alsatian ▪ Hindi ▪ Romansh ▪ Amharic ▪ Hungarian ▪ Russian ▪ Arabic ▪ Icelandic ▪ Saami ▪ Arabic (Egyptian) ▪ Igbo ▪ Sardinian ▪ Arabic (Modern Standard) ▪ Indonesian ▪ Scottish Gaelic ▪ Armenian ▪ Irish ▪ Serbian ▪ Assamese ▪ Italian ▪ Sesotho (Southern) ▪ Aymara ▪ Japanese ▪ Shona ▪ Azeri ▪ Jèrriais ▪ Sinhala ▪ Basque ▪ Kannada ▪ Slovak ▪ Belarusian ▪ Kazakh ▪ Slovenian ▪ Bengali ▪ Khmer ▪ Somali ▪ Berber (Tamazight) ▪ Kinyarwanda (Rwanda) ▪ Spanish ▪ Breton ▪ Kirghiz ▪ Swahili ▪ Bulgarian ▪ Klingon ▪ Swedish ▪ Burmese ▪ Korean ▪ Swiss German ▪ Canadian English ▪ Lao ▪ Tagalog ▪ Canadian French ▪ Latin ▪ Tamil ▪ Cantonese ▪ Latin American Spanish ▪ Telugu ▪ Catalan ▪ Latvian ▪ Thai ▪ Chichewa ▪ Lingala ▪ Tibetan ▪ Chinese (Mandarin) ▪ Lithuanian ▪ Tswana ▪ Chuvash ▪ Luganda ▪ Turkish ▪ Cornish ▪ Luxembourgish ▪ Ukrainian ▪ Corsican ▪ Macedonian ▪ Urdu ▪ Croatian ▪ Malagasy ▪ Uzbek ▪ Czech ▪ Malay ▪ Vietnamese ▪ Danish ▪ Malayalam ▪ Welsh ▪ Dari ▪ Maltese ▪ Xhosa ▪ Dutch ▪ Manx ▪ Yiddish ▪ English ▪ Marathi ▪ Yoruba ▪ English (American) ▪ Mongolian ▪ Zulu ▪ Esperanto ▪ Māori ▪ ▪ Estonian ▪ Navajo ▪ Faroese ▪ Nepali ▪ Finnish ▪ Norwegian ▪ Flemish ▪ Occitan ▪ French ▪ Papiamento ▪ Frisian ▪ Pashto ▪ Galician ▪ Persian ▪ Georgian ▪ Pidgin (Papua New ▪ German Guinea) ▪ Greek ▪ Polish ▪ Greenlandic ▪ Portuguese (Brazilian) ▪ Gujarati ▪ Portuguese (European) ▪ Haitian Creole ▪ Provençal -

The Linguistic Context 34

Variation and Change in Mainland and Insular Norman Empirical Approaches to Linguistic Theory Series Editor Brian D. Joseph (The Ohio State University, USA) Editorial Board Artemis Alexiadou (University of Stuttgart, Germany) Harald Baayen (University of Alberta, Canada) Pier Marco Bertinetto (Scuola Normale Superiore, Pisa, Italy) Kirk Hazen (West Virginia University, Morgantown, USA) Maria Polinsky (Harvard University, Cambridge, USA) Volume 7 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ealt Variation and Change in Mainland and Insular Norman A Study of Superstrate Influence By Mari C. Jones LEIDEN | BOSTON Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jones, Mari C. Variation and Change in Mainland and Insular Norman : a study of superstrate influence / By Mari C. Jones. p. cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-25712-2 (hardback : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-90-04-25713-9 (e-book) 1. French language— Variation. 2. French language—Dialects—Channel Islands. 3. Norman dialect—Variation. 4. French language—Dialects—France—Normandy. 5. Norman dialect—Channel Islands. 6. Channel Islands— Languages. 7. Normandy—Languages. I. Title. PC2074.7.J66 2014 447’.01—dc23 2014032281 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 2210-6243 ISBN 978-90-04-25712-2 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-25713-9 (e-book) Copyright 2015 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Nijhoff and Hotei Publishing. -

Language Transmission in France in the Course of the 20Th Century

https://archined.ined.fr Language transmission in France in the course of the 20th century François Héran, Alexandra Filhon et Christine Deprez Version Libre accès Licence / License CC Attribution - Pas d'Œuvre dérivée 4.0 International (CC BY- ND) POUR CITER CETTE VERSION / TO CITE THIS VERSION François Héran, Alexandra Filhon et Christine Deprez, 2002, "Language transmission in France in the course of the 20th century", Population & Societies: 1-4. Disponible sur / Availabe at: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12204/AXCwcStFDxhNsJusqTx6 POPU TTIION &SOCIÉTTÉÉS No.FEBRU ARY37 20062 Language transmission in France in the course of the 20th century François Héran *, Alexandra Filhon ** and Christine Deprez *** “French shall be the only language of education”, pro- Institute of Linguistics’ languages of the world data- claimed the Ministerial Order of 7 June 1880 laying base [4]. The ten most frequently recalled childhood down the model primary school regulations. “The lan- languages are cited by two thirds of the respondents, guage of the Republic is French”, recently added arti- while a much larger number are recalled by a bare cle 2 of the Constitution (1992). But do families follow handful. the strictures of state education and institutions? What The Families Survey distinguishes languages were the real linguistic practices of the population of “usually” spoken by parents with their children (fig- France in the last century? Sandwiched between the ure 1A) from those which they “also” spoke to them, monopoly of the national language and -

Sheep Based Cuisine Synthesis Report First Draft

CULTURE AND NATURE: THE EUROPEAN HERITAGE OF SHEEP FARMING AND PASTORAL LIFE RESEARCH THEME: SHEEP BASED CUISINE SYNTHESIS REPORT FIRST DRAFT By Zsolt Sári HUNGARIAN OPEN AIR MUSEUM January 2012 INTRODUCTION The history of sheep consume and sheep based cuisine in Europe. While hunger is a biologic drive, food and eating serve not only the purpose to meet physiological needs but they are more: a characteristic pillar of our culture. Food and nutrition have been broadly determined by environment and economy. At the same time they are bound to the culture and the psychological characteristics of particular ethnic groups. The idea of cuisine of every human society is largely ethnically charged and quite often this is one more sign of diversity between communities, ethnic groups and people. In ancient times sheep and shepherds were inextricably tied to the mythology and legends of the time. According to ancient Greek mythology Amaltheia was the she-goat nurse of the god Zeus who nourished him with her milk in a cave on Mount Ida in Crete. When the god reached maturity he created his thunder-shield (aigis) from her hide and the ‘horn of plenty’ (keras amaltheias or cornucopia) from her horn. Sheep breeding played an important role in ancient Greek economy as Homer and Hesiod testify in their writings. Indeed, during the Homeric age, meat was a staple food: lambs, goats, calves, giblets were charcoal grilled. In several Rhapsodies of Homer’s Odyssey, referring to events that took place circa 1180 BC, there is mention of roasting lamb on the spit. Homer called Ancient Thrace „the mother of sheep”. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Gascon Énonciatif System: Past, Present, and Future. A study of language contact, change, endangerment, and maintenance Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/12v9d1gx Author Marcus, Nicole Publication Date 2010 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Gascon Énonciatif System: Past, Present, and Future A study of language contact, change, endangerment, and maintenance by Nicole Elise Marcus A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Gary Holland, Chair Professor Leanne Hinton Professor Johanna Nichols Fall 2010 The Gascon Énonciatif System: Past, Present, and Future A study of language contact, change, endangerment, and maintenance © 2010 by Nicole Elise Marcus Abstract The Gascon Énonciatif System: Past, Present, and Future A study of language contact, change, endangerment, and maintenance by Nicole Elise Marcus Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Professor Gary Holland, Chair The énonciatif system is a defining linguistic feature of Gascon, an endangered Romance language spoken primarily in southwestern France, separating it not only from its neighboring Occitan languages, but from the entire Romance language family. This study examines this preverbal particle system from a diachronic and synchronic perspective to shed light on issues of language contact, change, endangerment, and maintenance. The diachronic source of this system has important implications regarding its current and future status. My research indicates that this system is an ancient feature of the language, deriving from contact between the original inhabitants of Gascony, who spoke Basque or an ancestral form of the language, and the Romans who conquered the region in 56 B.C.