Collins, Stephen (2011) Playwriting and Postcolonialism : Identifying the Key Factors in the Development and Diminution of Playwriting in Ghana 1916-2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

According to the South African Writer Nadine Gordimer, African Writers

The Grove. Working Papers on English Studies 24 (2017): 9-24. DOI: 10.17561/grove.v24.a1 THE RETURN OF THE BEEN-TO, THE BRINGER OF THE DIASPORA Isabel Gil Naveira Universidad de Oviedo Abstract Most male characters in the exile, analysed from a Post-Colonial perspective, were usually classified as either suffering from a neo-colonial process, and therefore rejecting tradition, or as keeping tradition and longing for going back to a patriarchal society. In this article, I aim to establish how Ama Ata Aidoo, in her play The Dilemma of a Ghost (1965), represents the feelings of unrootedness, loss and guilt associated to the main male character’s return to Africa. The use of the social and personal consequences that his comeback home to a matrilineal family has, will uncover the relation established between his family and his African American wife. In doing so, I will analyse how through an ‘insignificant’ song Aidoo tackles the controversial issue of the children of the diaspora and offers a solution to its rejection by the African population. Keywords: Africa; African American; exile; diaspora; identity; silence; neo- colonialism. Resumen La mayoría de los personajes masculinos en el exilio, analizados desde una perspectiva poscolonial, se solían clasificar en: aquellos bajo un proceso neocolonial, y que por tanto rechazaban la tradición, y aquellos que mantenían sus tradiciones y ansiaban volver a una sociedad patriarcal. En este artículo, intento establecer cómo Ama Ata Aidoo, en su obra The Dilemma of a Ghost (1965), representa los sentimientos de desarraigo, pérdida y culpabilidad asociados a la vuelta a África del personaje masculino principal. -

Hrudní Endovaskulární Graft Zenith Alpha™ Návod K Použití

MEDICAL EN Zenith Alpha™ Thoracic Endovascular Graft 15 Instructions for Use CS Hrudní endovaskulární graft Zenith Alpha™ 22 Návod k použití DA Zenith Alpha™ torakal endovaskulær protese 29 Brugsanvisning DE Zenith Alpha™ thorakale endovaskuläre Prothese 36 Gebrauchsanweisung EL Θωρακικό ενδαγγειακό μόσχευμα Zenith Alpha™ 44 Οδηγίες χρήσης ES Endoprótesis vascular torácica Zenith Alpha™ 52 Instrucciones de uso FR Endoprothèse vasculaire thoracique Zenith Alpha™ 60 Mode d’emploi HU Zenith Alpha™ mellkasi endovaszkuláris graft 67 Használati utasítás IT Protesi endovascolare toracica Zenith Alpha™ 74 Istruzioni per l’uso NL Zenith Alpha™ thoracale endovasculaire prothese 81 Gebruiksaanwijzing NO Zenith Alpha™ torakalt endovaskulært implantat 88 Bruksanvisning PL Piersiowy stent-graft wewnątrznaczyniowy Zenith Alpha™ 95 Instrukcja użycia PT Prótese endovascular torácica Zenith Alpha™ 103 Instruções de utilização SV Zenith Alpha™ endovaskulärt graft för thorax 110 Bruksanvisning Patient I.D. Card Included I-ALPHA-TAA-1306-436-01 *436-01* ENGLISH ČESKY TABLE OF COntents OBSAH 1 DEVICE DESCRIPTION ....................................................................... 15 1 POPIS ZAŘÍZENÍ ....................................................................................... 22 1.1 Zenith Alpha Thoracic Endovascular Graft .........................................15 1.1 Hrudní endovaskulární graft Zenith Alpha .............................................. 22 1.2 Introduction System ...................................................................................15 -

Nation, Power and Dissidence in Third-Generation Nigerian Poetry in English by Sule E

Nation, power and dissidence in third-generation Nigerian poetry in English by Sule E. Egya TERMS of USE The African Humanities Program has made this electronic version of the book available on the NISC website for free download to use in research or private study. It may not be re- posted on book or other digital repositories that allow systematic sharing or download. For any commercial or other uses please contact the publishers, NISC (Pty) Ltd. Print copies of this book and other titles in the African Humanities Series are available through the African Books Collective. © African Humanities Program Dedication Fondly for: Anyalewa Emmanuella, Oyigwu Desmond and Egya Nelson. Love, love, and more love. About the Series The African Humanities Series is a partnership between the African Humanities Program (AHP) of the American Council of Learned Societies and academic publishers NISC (Pty) Ltd*. The Series covers topics in African histories, languages, literatures, philosophies, politics and cultures. Submissions are solicited from Fellows of the AHP, which is administered by the American Council of Learned Societies and financially supported by the Carnegie Corporation of New York. The purpose of the AHP is to encourage and enable the production of new knowledge by Africans in the five countries designated by the Carnegie Corporation: Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, and Uganda. AHP fellowships support one year’s work free from teaching and other responsibilities to allow the Fellow to complete the project proposed. Eligibility for the fellowship in the five countries is by domicile, not nationality. Book proposals are submitted to the AHP editorial board which manages the peer review process and selects manuscripts for publication by NISC. -

A Journal of African Studies

UCLA Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies Title Towards an Authentic African Theatre Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/72j9n7n2 Journal Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies, 19(2-3) ISSN 0041-5715 Author Agovi, K.E. Publication Date 1991 DOI 10.5070/F7192-3016790 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California 67 TOWARDS AN AUTHENITC AFRICAN TIIEATRE K. E. Agovi This paper deals with the emergence of the literary theater in Africa and its aspiration towards a sense of an ultimate African identity. Since the literature on this subject is extensive,1 we will attempt no more than a historical survey of significant developments. Although this issue has often inspired passionate disagreement, and various viewpoints have been expressed, there seems to be an emerging consensus. There are those who have predicted its achievement "when the conceptual and creative approaches [in the literary theater can] cast off the mental constraints imposed by acquired Euro-American plays."2 There are others who wish to see it realized as a "synthesis" of African and European ideas and experience. This idea has often implied an awareness of the fact that "the creative personality in any place and period of human history has always been enriched by experiences external to his native creative-cultural heritage. "3 And as Keita Fodeba has also pointed out, "a spectacle is authentic (in the theater) when it recreates faithfully the most characteristic aspects of life which it wants to show on stage. "4 For the purpose of this article, the concept of an "authentic" African theater may be defined as that form of creativity in the theater which is rooted in the composite tenor of African experience, embodying a relationship of relevance between the past and present, and which in effect reflects principles of African performance aesthetics. -

Select Bibliography

Select Bibliography by the late F. Seymour-Smith Reference books and other standard sources of literary information; with a selection of national historical and critical surveys, excluding monographs on individual authors (other than series) and anthologies. Imprint: the place of publication other than London is stated, followed by the date of the last edition traced up to 1984. OUP- Oxford University Press, and includes depart mental Oxford imprints such as Clarendon Press and the London OUP. But Oxford books originating outside Britain, e.g. Australia, New York, are so indicated. CUP - Cambridge University Press. General and European (An enlarged and updated edition of Lexicon tkr WeltliU!-atur im 20 ]ahrhuntkrt. Infra.), rev. 1981. Baker, Ernest A: A Guilk to the B6st Fiction. Ford, Ford Madox: The March of LiU!-ature. Routledge, 1932, rev. 1940. Allen and Unwin, 1939. Beer, Johannes: Dn Romanfohrn. 14 vols. Frauwallner, E. and others (eds): Die Welt Stuttgart, Anton Hiersemann, 1950-69. LiU!-alur. 3 vols. Vienna, 1951-4. Supplement Benet, William Rose: The R6athr's Encyc/opludia. (A· F), 1968. Harrap, 1955. Freedman, Ralph: The Lyrical Novel: studies in Bompiani, Valentino: Di.cionario letU!-ario Hnmann Hesse, Andrl Gilk and Virginia Woolf Bompiani dille opn-e 6 tUi personaggi di tutti i Princeton; OUP, 1963. tnnpi 6 di tutu le let16ratur6. 9 vols (including Grigson, Geoffrey (ed.): The Concise Encyclopadia index vol.). Milan, Bompiani, 1947-50. Ap of Motkm World LiU!-ature. Hutchinson, 1970. pendic6. 2 vols. 1964-6. Hargreaves-Mawdsley, W .N .: Everyman's Dic Chambn's Biographical Dictionary. Chambers, tionary of European WriU!-s. -

Francis Davis Imbuga: the Story of His Life

FRANCIS DAVIS IMBUGA: THE STORY OF HIS LIFE BY MAKHAKHA, JOSEPH WANGILA C50/63702/2013 A RESEARCH PROJECT IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER DEGREE IN LITERATURE SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF LITERATURE, FACULTY OF ARTS- UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI 2015 i FRANCIS DAVIS IMBUGA THE STORY OF HIS LIFE ii DECLARATION This project is my original work and has not been submitted for the award of a degree in another University: Candidate: Makhakha Joseph Wangila SIGNATURE _________________________DATE ___________________ This Project has been submitted for examination with our approval as university supervisors: FIRST SUPERVISOR: PROF. HENRY INDANGASI SIGN: _________________________ DATE_______________________ SECOND SUPERVISOR: PROF. CIAIRUNJI CHESAINA SIGN: _________________________DATE _______________________ iii TABLE OF CONTENTS DECLARATION ...................................................................................................................... iii ABSTRACT .............................................................................................................................. vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................... vii CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background to the study ........................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Statement of the problem ..................................................................................................... -

A HISTORY of TWENTIETH CENTURY AFRICAN LITERATURE.Rtf

A HISTORY OF TWENTIETH CENTURY AFRICAN LITERATURES Edited by Oyekan Owomoyela UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA PRESS © 1993 by the University of Nebraska Press All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America The paper in this book meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI 239.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A History of twentieth-century African literatures / edited by Oyekan Owomoyela. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8032-3552-6 (alk. paper) — ISBN 0-8032-8604-x (pbk.: alk. paper) I. Owomoyela, Oyekan. PL80I0.H57 1993 809'8896—dc20 92-37874 CIP To the memory of John F. Povey Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction I CHAPTER I English-Language Fiction from West Africa 9 Jonathan A. Peters CHAPTER 2 English-Language Fiction from East Africa 49 Arlene A. Elder CHAPTER 3 English-Language Fiction from South Africa 85 John F. Povey CHAPTER 4 English-Language Poetry 105 Thomas Knipp CHAPTER 5 English-Language Drama and Theater 138 J. Ndukaku Amankulor CHAPTER 6 French-Language Fiction 173 Servanne Woodward CHAPTER 7 French-Language Poetry 198 Edris Makward CHAPTER 8 French-Language Drama and Theater 227 Alain Ricard CHAPTER 9 Portuguese-Language Literature 240 Russell G. Hamilton -vii- CHAPTER 10 African-Language Literatures: Perspectives on Culture and Identity 285 Robert Cancel CHAPTER II African Women Writers: Toward a Literary History 311 Carole Boyce Davies and Elaine Savory Fido CHAPTER 12 The Question of Language in African Literatures 347 Oyekan Owomoyela CHAPTER 13 Publishing in Africa: The Crisis and the Challenge 369 Hans M. -

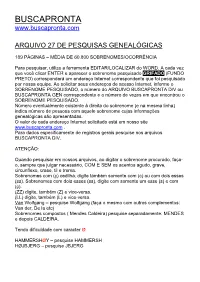

Adams Adkinson Aeschlimann Aisslinger Akkermann

BUSCAPRONTA www.buscapronta.com ARQUIVO 27 DE PESQUISAS GENEALÓGICAS 189 PÁGINAS – MÉDIA DE 60.800 SOBRENOMES/OCORRÊNCIA Para pesquisar, utilize a ferramenta EDITAR/LOCALIZAR do WORD. A cada vez que você clicar ENTER e aparecer o sobrenome pesquisado GRIFADO (FUNDO PRETO) corresponderá um endereço Internet correspondente que foi pesquisado por nossa equipe. Ao solicitar seus endereços de acesso Internet, informe o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO, o número do ARQUIVO BUSCAPRONTA DIV ou BUSCAPRONTA GEN correspondente e o número de vezes em que encontrou o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO. Número eventualmente existente à direita do sobrenome (e na mesma linha) indica número de pessoas com aquele sobrenome cujas informações genealógicas são apresentadas. O valor de cada endereço Internet solicitado está em nosso site www.buscapronta.com . Para dados especificamente de registros gerais pesquise nos arquivos BUSCAPRONTA DIV. ATENÇÃO: Quando pesquisar em nossos arquivos, ao digitar o sobrenome procurado, faça- o, sempre que julgar necessário, COM E SEM os acentos agudo, grave, circunflexo, crase, til e trema. Sobrenomes com (ç) cedilha, digite também somente com (c) ou com dois esses (ss). Sobrenomes com dois esses (ss), digite com somente um esse (s) e com (ç). (ZZ) digite, também (Z) e vice-versa. (LL) digite, também (L) e vice-versa. Van Wolfgang – pesquise Wolfgang (faça o mesmo com outros complementos: Van der, De la etc) Sobrenomes compostos ( Mendes Caldeira) pesquise separadamente: MENDES e depois CALDEIRA. Tendo dificuldade com caracter Ø HAMMERSHØY – pesquise HAMMERSH HØJBJERG – pesquise JBJERG BUSCAPRONTA não reproduz dados genealógicos das pessoas, sendo necessário acessar os documentos Internet correspondentes para obter tais dados e informações. DESEJAMOS PLENO SUCESSO EM SUA PESQUISA. -

(Auto)Biography: Ama Ata Aidoo's Literary Quest

Esther Pujolràs i Noguer An African (Auto)biography: Ama Ata Aidoo’s Literary Quest This dissertation has been supervised by Dr. Felicity Hand Cranham Departament de Filologia Anglesa i Germanística Facultat de Filosofia i Lletres Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona 2010 i Contents Introduction. As Always ... a Painful Declaration of Independence, 1 Part I. The Cave: Colonialism in Black and White, 23 One. Unveiling the Ghost: Heart of Darkness or Africa-Chronotope Zero, 29 Two. (Auto)Biographical Fiction: The Facing and De-Facing of Africa, 59 I. Lettering the Stone: Négritude and the Pan-African Ideal, 73 II. De-Facing Négritude: The Mother Africa Trope and the Discourse of Double Consciousness, 102 Part II. The Cave Revisited: Towards a Subjectification of Africa and African Women, 127 Three. Without Cracks? Fissures in the Cave: The Middle Passage, 133 I. Nation, Home, Africa … The Birth of the African Dilemma or The Dilemma of a Ghost, 144 II. Myth, History, Africa: Anowa As the Source of the Dilemma?, 164 Four. The Postcolonial Arena: No Sweetness Here or the Travails of Africans after Independence, 189 I. Problematizing History and the Nation Paradox, 194 II. Writing the Independent Nation, 207 Five. The White Hole: Our Sister Killjoy or Reflections from a Black-Eyed Squint, 275 I. Good Night Africa, Good Morning Europe: The Limits of Writing Back and the Call for a Postcolonial Readership, 280 II. Ja, Das Schwartze Mädchen: The Challenge of Tradition and the Female African Voice, 290 Conclusions. My Dear Sister, the Original Phoenix Must Have Been a Woman, 337 Select Bibliography, 389 ii iii Acknowledgements I am indebted to the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (Micim) for the mobility grant (Ref. -

Rūta Stanevičiūtė Nick Zangwill Rima Povilionienė Editors Between Music

Numanities - Arts and Humanities in Progress 7 Rūta Stanevičiūtė Nick Zangwill Rima Povilionienė Editors Of Essence and Context Between Music and Philosophy Numanities - Arts and Humanities in Progress Volume 7 Series Editor Dario Martinelli, Faculty of Creative Industries, Vilnius Gediminas Technical University, Vilnius, Lithuania [email protected] The series originates from the need to create a more proactive platform in the form of monographs and edited volumes in thematic collections, to discuss the current crisis of the humanities and its possible solutions, in a spirit that should be both critical and self-critical. “Numanities” (New Humanities) aim to unify the various approaches and potentials of the humanities in the context, dynamics and problems of current societies, and in the attempt to overcome the crisis. The series is intended to target an academic audience interested in the following areas: – Traditional fields of humanities whose research paths are focused on issues of current concern; – New fields of humanities emerged to meet the demands of societal changes; – Multi/Inter/Cross/Transdisciplinary dialogues between humanities and social and/or natural sciences; – Humanities “in disguise”, that is, those fields (currently belonging to other spheres), that remain rooted in a humanistic vision of the world; – Forms of investigations and reflections, in which the humanities monitor and critically assess their scientific status and social condition; – Forms of research animated by creative and innovative humanities-based -

African Women's Empowerment: a Study in Amma Darko's Selected

African women’s empowerment : a study in Amma Darko’s selected novels Koumagnon Alfred Djossou Agboadannon To cite this version: Koumagnon Alfred Djossou Agboadannon. African women’s empowerment : a study in Amma Darko’s selected novels. Linguistics. Université du Maine; Université d’Abomey-Calavi (Bénin), 2018. English. NNT : 2018LEMA3008. tel-02049712 HAL Id: tel-02049712 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02049712 Submitted on 26 Feb 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THESE DE DOCTORAT DE LE MANS UNIVERSITE ET DE L’UNIVERSITE D’ABOMEY-CALAVI COMUE UNIVERSITE BRETAGNE LOIRE ÉCOLE DOCTORALE N° 595 ÉCOLE DOCTORALE PLURIDISCIPLINAIRE Arts, Lettres, Langues «Espaces, Cultures et Développement» Spécialité : Littérature africaine anglophone Par Koumagnon Alfred DJOSSOU AGBOADANNON AFRICAN WOMEN’S EMPOWERMENT: A STUDY IN AMMA DARKO’S SELECTED NOVELS Thèse présentée et soutenue à l’Université d’Abomey-Calavi, le 17 décembre 2018 Unités de recherche : 3 LAM Le Mans Université et GRAD Université d’Abomey-Calavi Thèse N° : 2018LEMA3008 Rapporteurs avant soutenance : Komla Messan NUBUKPO, Professeur Titulaire / Université de Lomé / TOGO Philip WHYTE, Professeur Titulaire / Université François Rabelais de Tours / FRANCE Laure Clémence CAPO-CHICHI ZANOU, Professeur Titulaire / Université d’Abomey-Calavi/BENIN Composition du Jury : Présidente : Laure Clémence CAPO-CHICHI ZANOU, Professeur Titulaire / Université d’Abomey-Calavi/BENIN Examinateurs : Augustin Y. -

Shakespearean Cinemas / Global Directions

Shakespearean Cinemas / Global Directions Burnett, M. (2020). Shakespearean Cinemas / Global Directions. In R. Jackson (Ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Screen (pp. 52-64). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108367479 Published in: The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Screen Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Copyright 2020 Cambridge University Press This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:04. Oct. 2021 4 MARK THORNTON BURNETT Shakespearean Cinemas/Global Directions Once pushed to the sidelines of scholarly enquiry, world cinema is increasingly seen as central to the field of Shakespeare on film. As a wealth of examples begin to be appreciated, so do new methodological approaches present themselves.