Acta 116 Kor.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE TOWN HALL Station on the Route Charlemagne Table of Contents

THE TOWN HALL Station on the Route Charlemagne Table of contents Route Charlemagne 3 Palace of Charlemagne 4 History of the Building 6 Gothic Town Hall 6 Baroque period 7 Neo-Gothic restoration 8 Destruction and rebuilding 9 Tour 10 Foyer 10 Council Hall 11 White Hall 12 Master Craftsmen‘s Court 13 Master Craftsmen‘s Kitchen 14 “Peace Hall“ (Red Hall) 15 Ark Staircase 16 Charlemagne Prize 17 Coronation Hall 18 Service 22 Information 23 Imprint 23 7 6 5 1 2 3 4 Plan of the ground floor 2 The Town Hall Route Charlemagne Aachen‘s Route Charlemagne connects significant locations around the city to create a path through history – one that leads from the past into the future. At the centre of the Route Charlemagne is the former palace complex of Charlemagne, with the Katschhof, the Town Hall and the Cathedral still bearing witness today of a site that formed the focal point of the first empire of truly European proportions. Aachen is a historical town, a centre of science and learning, and a European city whose story can be seen as a history of Europe. This story, along with other major themes like religion, power, economy and media, are all reflected and explored in places like the Cathedral and the Town Hall, the International Newspaper Museum, the Grashaus, Haus Löwenstein, the Couven-Museum, the Axis of Science, the SuperC of the RWTH Aachen University and the Elisenbrunnen. The central starting point of the Route Charlemagne is the Centre Charlemagne, the new city museum located on the Katschhof between the Town Hall and the Cathedral. -

Isabelle Dolezalek Arabic Script on Christian Kings Das Mittelalter Perspektiven Mediävistischer Forschung

Isabelle Dolezalek Arabic Script on Christian Kings Das Mittelalter Perspektiven mediävistischer Forschung Beihefte Herausgegeben von Ingrid Baumgärtner, Stephan Conermann und Thomas Honegger Band 5 Isabelle Dolezalek Arabic Script on Christian Kings Textile Inscriptions on Royal Garments from Norman Sicily Gedruckt mit freundlicher Unterstützung der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) ISBN 978-3-11-053202-9 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-053387-3 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-053212-8 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Typesetting: Satzstudio Borngräber, Dessau-Roßlau Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Gedruckt auf säurefreiem Papier Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Contents Preface — IX Introduction — XI Chapter I Shaping Perceptions: Reading and Interpreting the Norman Arabic Textile Inscriptions — 1 1 Arabic-Inscribed Textiles from Norman and Hohenstaufen Sicily — 2 2 Inscribed Textiles and Arabic Inscriptions in European Medieval Arts — 43 3 Historical Receptions of the Ceremonial Garments from Norman Sicily — 51 4 Approaches to Arabic Inscriptions in European Medieval Arts: Methodological Considerations — 64 Chapter II An Imported Ornament? Comparing the Functions -

The Peace of Augsburg in Three Imperial Cities by Istvan

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Waterloo's Institutional Repository Biconfessionalism and Tolerance: The Peace of Augsburg in Three Imperial Cities by Istvan Szepesi A thesis presented to the University Of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in History Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2016 © Istvan Szepesi 2016 I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract In contrast to the atmosphere of mistrust and division between confessions that was common to most polities during the Reformation era, the Peace of Augsburg, signed in 1555, declared the free imperial cities of the Holy Roman Empire a place where both Catholics and Lutherans could live together in peace. While historians readily acknowledge the exceptional nature of this clause of the Peace, they tend to downplay its historical significance through an undue focus on its long-term failures. In order to challenge this interpretation, this paper examines the successes and failures of the free imperial cities’ implementation of the Peace through a comparative analysis of religious coexistence in Augsburg, Cologne, and Nuremberg during the Peace’s 63- year duration. This investigation reveals that while religious coexistence did eventually fail first in Nuremberg and then in Cologne, the Peace made major strides in the short term which offer important insights into the nature of tolerance and confessional conflict in urban Germany during the late Reformation era. -

Bremen (Germany) No 1087

buildings (36ha), surrounded by an outer protection zone (376ha). The town hall has two parts: the Old Town Hall Bremen (Germany) initially built in 1409 on the north side of the market place, renovated in the early 17th century, and the New Town Hall No 1087 that was built in the early 20th century as an addition facing the cathedral square. The Old Town Hall is a two-storey hall building with a rectangular floor plan, 41.5 x 15.8m. It is described as a 1. BASIC DATA transverse rectangular Saalgeschossbau (i.e. a multi-storey State Party: Federal Republic of Germany construction built to contain a large hall). It has brick walls and wooden floors structures. The exterior is in exposed Name of property: The town hall and Roland on the brick with alternating dark and light layers; the decorative marketplace of Bremen elements and fittings are in stone. The roof is covered by Location: The City of Bremen green copper. The ground floor is formed of one large hall with oak pillars; it served for merchants and theatrical Date received: 22 January 2002 performances. The upper floor has the main festivity hall of the same dimensions. Between the windows, there are Category of property: stone statues representing the emperor and prince electors, In terms of the categories of cultural property set out in which date from the original Gothic phase, integrated with Article 1 of the 1972 World Heritage Convention, this is a late-Renaissance sculptural decoration symbolising civic monument. It is a combination of architectural work and autonomy. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title A Second Refuge: French Opera and the Huguenot Migration, c. 1680 - c. 1710 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6ck4p872 Author Ahrendt, Rebekah Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California A Second Refuge French Opera and the Huguenot Migration, c. 1680 – c. 1710 By Rebekah Susannah Ahrendt A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kate van Orden, Chair Professor Richard Taruskin Professor Peter Sahlins Fall 2011 A Second Refuge French Opera and the Huguenot Migration, c. 1680 – c. 1710 Copyright 2011 by Rebekah Susannah Ahrendt 1 Abstract A Second Refuge French Opera and the Huguenot Migration, c. 1680 – c. 1710 by Rebekah Susannah Ahrendt Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Kate van Orden, Chair This dissertation examines the brief flowering of French opera on stages outside of France around the turn of the eighteenth century. I attribute the sudden rise and fall of interest in the genre to a large and noisy migration event—the flight of some 200,000 Huguenots from France. Dispersed across Western Europe and beyond, Huguenots maintained extensive networks that encouraged the exchange of ideas and of music. And it was precisely in the great centers of the Second Refuge that French opera was performed. Following the wide-ranging career path of Huguenot impresario, novelist, poet, and spy Jean-Jacques Quesnot de la Chenée, I construct an alternative history of French opera by tracing its circulation and transformation along Huguenot migration routes. -

{Download PDF} Netherland Ebook, Epub

NETHERLAND PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Joseph O'Neill | 300 pages | 04 Mar 2009 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007275700 | English | London, United Kingdom Netherland PDF Book Cancel GO. EU Science Hub. Columbia University Press. With Indonesia's independence, a federal constitution was considered too heavy as the economies of Suriname and the Netherlands Antilles were insignificant compared to that of the Netherlands. III, Harper Bros. Iron ore brought a measure of prosperity, and was available throughout the country, including bog iron. It is the northern city that enjoys life to the fullest. The country remained neutral during World War I. The region called the Low Countries comprising Belgium , the Netherlands and Luxembourg and the Country of the Netherlands, have the same toponymy. Most of present-day Netherlands became part of Middle Francia , which was a weak kingdom and subject of numerous partitions and annexation attempts by its stronger neighbours. Zeeland and South Holland produce a lot of butter, which contains a larger amount of milkfat than most other European butter varieties. The circuit was purpose-built for the Dutch TT in , with previous events having been held on public roads. The Dutch East India Company was established in , and by the end of the 17th century, Holland was one of the great sea and colonial powers of Europe. Art museums Vermeer Centre Delft Add to itinerary. It is relatively safe to travel by rail from city to city, compared to some other European countries. Other activities include sailing, fishing, cycling, and bird watching. Consulate General Amsterdam. The Netherlands has multiple music traditions. You'll see -- or smell -- Amsterdam's infamous "coffee shops" where marijuana is legally sold and consumed. -

In Zuid-Limburg

Willkommen in Zuid-Limburg Die Region Aktivitäten Familie und Kinder Wellness und Gesundheit Entschleunigung und Spiritualität Kultur und Events Unterkünfte und Gastronomie Highlights und Service Zuid-Limburg – Genieße Dein Leben! Willkommen in Zuid-Limburg, der südlichsten Region der Niederlande! Sanfte kleinem Raum. Zuid-Limburg ist der südlichste Hügel, saftige Wiesen und malerische Dörfer. So Teil der Provinz Limburg, zu der außerdem die empfängt Sie Zuid-Limburg frei nach dem Motto: Regionen Noord-Limburg und Midden-Limburg Entspann Dich und genieße Dein Leben! zählen. Die Region erstreckt sich über eine Fläche von cirka 661 km2, ungefähr vergleichbar mit der Große Vielfalt auf kleinem Raum Fläche von Köln und Düsseldorf zusammen. Von Aachen nur einen Steinwurf entfernt, von Vom östlichsten Punkt, der Stadt Heerlen, bis Köln und Düsseldorf in etwa einer Stunde zu zum westlichsten Punkt, der Stadt Maastricht, erreichen, grenzt Zuid-Limburg im Osten an sind es gerade mal etwa 24 Kilometer! Den Nor- Deutschland, im Süden und Westen an Belgien. den und Süden der Region trennen ungefähr Als Mittelpunkt dieses Dreiländerecks „Nieder- 40 Kilometer. Zuid-Limburg ist eine Urlaubsre- lande – Deutschland – Belgien“ besticht Zuid- gion, die das Prädikat „klein aber fein“ wahrlich Limburg durch seine „grenzenlose“ Vielfalt auf verdient. 2 3 Die Region 6 Aktivitäten 16 Familie und Kinder 22 Wellness und Gesundheit 26 Entschleunigung und Spiritualität 30 Kultur und Events 32 Unterkünfte und Gastronomie 38 Highlights 44 Service 50 ankommen, runterkommen, Adressenliste 54 genießen Auf kleinem Raum überzeugt die Region Zuid- Kurzurlaub in Zuid-Limburg. Wir freuen uns nach Valkenburg. Tun Sie Ihrem Körper etwas Gutes und ent- Limburg mit einer großen Auswahl attraktiver schon auf Sie! spannen Sie sich im 32 Grad warmen Thermalwasser in den Angebote für Sie und Ihre Begleiter. -

Soil Erosion and the Adaptive Cycle Metaphor

Soil erosion and the adaptive cycle metaphor Luuk Dorren and Anton Imeson IBED - Physical Geography, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [email protected] / [email protected] 1 Introduction The landscapes we live in and the changes they undergo play an important part in the qualities of our lives as development of infrastructure and industry, housing and exploitation of the earth's resources are still prerequisites for growth in the current western economies. But landscapes also provide additional natural goods and services of value to us, such as recreation, water and climate regulation, food production, tourism and nature conservation. These goods and services, or so-called functions of nature (de Groot, 1992), can be provided because of the existence of soil, which is a medium between the solid earth and the sphere we live our daily life in. The medium soil is constantly subject to change, of which the causes are dependent on the geographical position of the soil. Examples of causes are activity of microorganisms and animals that live in the soil, weathering of bedrock, which increases the thickness of the soil, input of organic material by farmers or dead plant material. Another example is soil erosion. Soil erosion is identified by the European Commission as one of the major threats to soils in Europe (CEC, 2002). At the time of writing, the European Union is engaged in the process of developing a policy for soil protection and erosion will be one of the focal points in it. During the previous decades much research has been done on soil erosion in different parts in Europe. -

The Geology of the Belvédère Pit and Its Wider Geographical Setting

The geology of the Belvédère pit and its wider geographical setting 2.1 Introduction The aim of this chapter is to give a short description of the Middie and Late Pleistocene deposits at Maastricht-Belvé- dère in order to provide the reader with a general geological framework, certain aspects of which will be discussed in greater detail in the rest of this volume. Before we concen- trate our attention on the Belvédère-pit, a description will be given of the general geological setting of the Ouaternary deposits at Belvédère in a summary of the geology of the region, i.e. the southern part of the Dutch province of Limburg (2.2). The paragraphs following this regional setting discuss the lithology and lithostratigraphy of the recorded sections in the pit (2.3.2), the palaeosols present (2.3.3), and the palaeoenvironment during the formation of the deposits (2.3.4). Finally, the relative and absolute dat- ing evidence of the different units is presented in section 2.3.5, while section 2.3.6 gives a first synthesis of the Mid die Pleistocene sequence at Belvédère. 2.2 The wider geological setting South Limburg is situated in the transitional fault-block area between the Dutch Central Graben and the Ardennes highlands, as shown in figure 7. The continuation of the Central Graben into Germany is called the Rurtal Graben (fig. 7). In general terms, the Ardennes Massif may be seen as an erosional area, while the Central Graben is a deposi- tional environment. In South Limburg there are a large number of southeast/northwest orientated faults, of which the northernmost Feldbiss fault is the most pronounced. -

Meeting Place SPEYER

Meeting Place SPEYER The 2,000 Year-OldSPEYER City on the Rhine Table of Contents Noviomagus – Civitas Nemetum – Spira – these three names have stood, over the course of more Emperors and Bishops 5 than 2,000 years, for an urban settlement on the left bank of the Rhine. Today this settlement is Imperial Diets and the Reformation 6 called Speyer, the Cathedral City, the Imperial City with its proud, powerful and historically sig- Science and Administration 7 nificant examples of religious architecture, its smart building facades from different architectural Art and Culture 8 periods, its quiet squares and side streets that are full of nooks and crannies. Festivals and Hospitality 10 Celts, Roman soldiers, wars and revolutions, ecclesi- A Walk Through the City 13 astical and secular rulers, and above all, the will of its citizens have shaped the face of the city. Already The Rhine-Neckar Metropolitan Region 24 determined to have been a settlement during Celtic times, the first Roman military camp came into exist- Shopping in Speyer 25 ence in the year 10 B.C. between what are today the Bishop’s Residence and City Hall. The civilian settle- Interesting Sights and Museums 26 ment that developed, first called “Noviomagus” and then “Civitas Nemetum” grew, despite many set- Imprint 27 backs, into a regional government and commercial center. In the 6th century, it was referred to as “Spira” in documents. View of the City of Speyer/Stadtansicht Meeting Place SPEYER · The 2,000 Year-Old City on the Rhine 3 Emperors and BishopsSPEYER During the rule of the Salian emperors (1024 – 1125), In 1111, the last Salian, Heinrich IV bestowed basic Speyer rose to become one of the most important freedoms on the populace. -

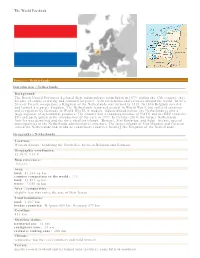

The World Factbook Europe :: Netherlands Introduction :: Netherlands Background: the Dutch United Provinces Declared Their Indep

The World Factbook Europe :: Netherlands Introduction :: Netherlands Background: The Dutch United Provinces declared their independence from Spain in 1579; during the 17th century, they became a leading seafaring and commercial power, with settlements and colonies around the world. After a 20-year French occupation, a Kingdom of the Netherlands was formed in 1815. In 1830 Belgium seceded and formed a separate kingdom. The Netherlands remained neutral in World War I, but suffered invasion and occupation by Germany in World War II. A modern, industrialized nation, the Netherlands is also a large exporter of agricultural products. The country was a founding member of NATO and the EEC (now the EU) and participated in the introduction of the euro in 1999. In October 2010, the former Netherlands Antilles was dissolved and the three smallest islands - Bonaire, Sint Eustatius, and Saba - became special municipalities in the Netherlands administrative structure. The larger islands of Sint Maarten and Curacao joined the Netherlands and Aruba as constituent countries forming the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Geography :: Netherlands Location: Western Europe, bordering the North Sea, between Belgium and Germany Geographic coordinates: 52 30 N, 5 45 E Map references: Europe Area: total: 41,543 sq km country comparison to the world: 135 land: 33,893 sq km water: 7,650 sq km Area - comparative: slightly less than twice the size of New Jersey Land boundaries: total: 1,027 km border countries: Belgium 450 km, Germany 577 km Coastline: 451 km Maritime claims: -

Europe Disclaimer

World Small Hydropower Development Report 2019 Europe Disclaimer Copyright © 2019 by the United Nations Industrial Development Organization and the International Center on Small Hydro Power. The World Small Hydropower Development Report 2019 is jointly produced by the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) and the International Center on Small Hydro Power (ICSHP) to provide development information about small hydropower. The opinions, statistical data and estimates contained in signed articles are the responsibility of the authors and should not necessarily be considered as reflecting the views or bearing the endorsement of UNIDO or ICSHP. Although great care has been taken to maintain the accuracy of information herein, neither UNIDO, its Member States nor ICSHP assume any responsibility for consequences that may arise from the use of the material. This document has been produced without formal United Nations editing. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or its economic system or degree of development. Designations such as ‘developed’, ‘industrialized’ and ‘developing’ are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgment about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. Mention of firm names or commercial products does not constitute an endorsement by UNIDO. This document may be freely quoted or reprinted but acknowledgement is requested.