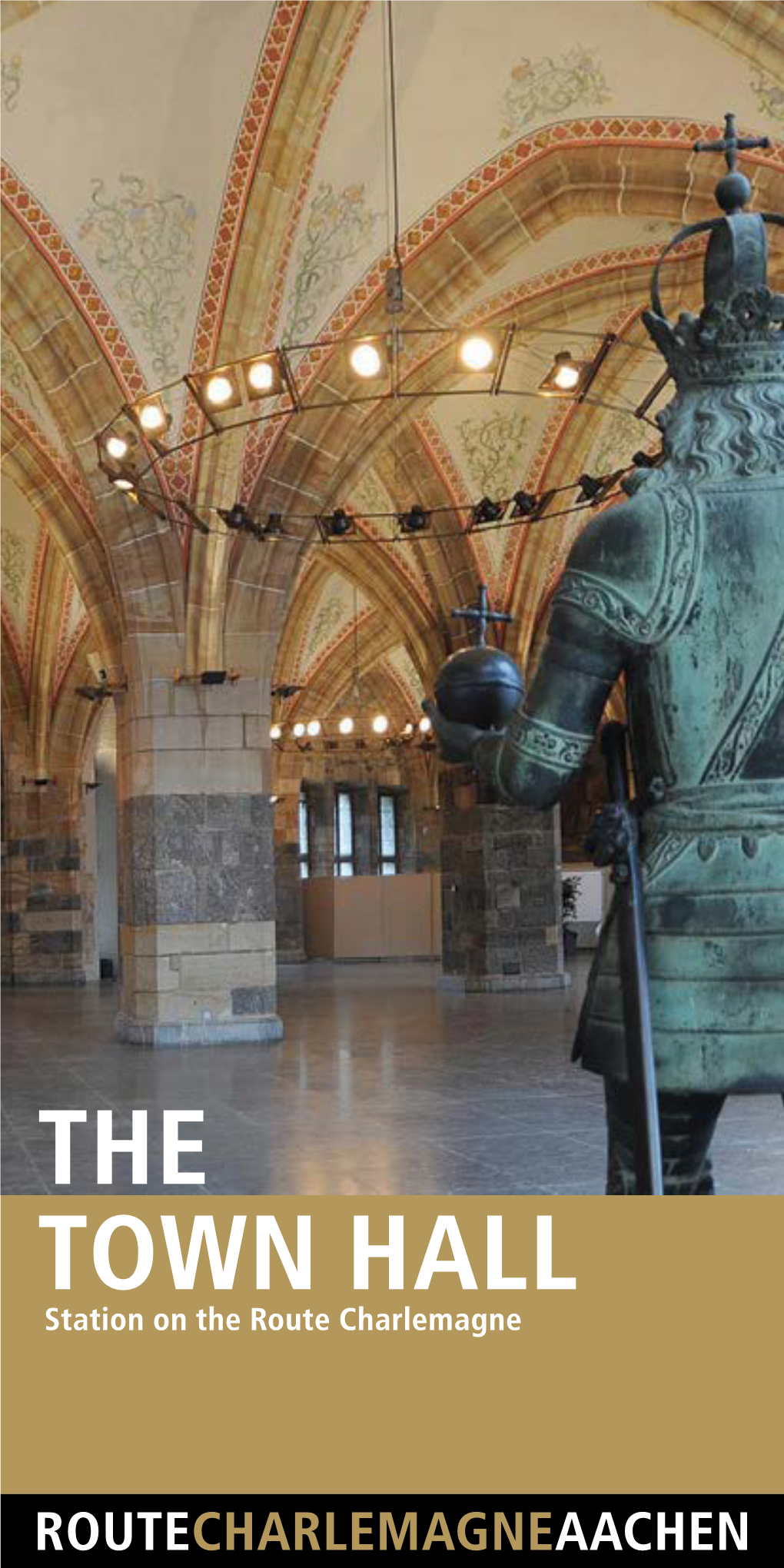

THE TOWN HALL Station on the Route Charlemagne Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History and Culture

HISTORY AND CULTURE A HAMBURG PORTUGUESE IN THE SERVICE OF THE HAGANAH: THE TRIAL AGAINST DAVID SEALTIEL IN HAMBURG (1937) Ina Lorenz (Hamburg. Germany) Spotlighted in the story here to be told is David de Benjamin Sealtiel (Shaltiel, 1903–1969), a Sephardi Jew from Hamburg, who from 1934 worked for the Haganah in Palestine as a weapons buyer. He paid for that activity with 862 days in incarceration under extremely difficult conditions of detention in the concentration camps of the SS.1 Jewish Immigration into Palestine and the Founding of the Haganah2 In order to be able to effectively protect the new Jewish settlements in Palestine from Arab attacks, and since possession of weapons was prohibited under the British Mandatory administration, arms and munitions initially were generally being smuggled into Palestine via French- controlled Syria. The leaders of the Haganah and Histadrut transformed the Haganah with the help of the Jewish Agency from a more or less untrained militia into a paramilitary group. The organization, led by Yisrael Galili (1911–1986), which in the rapidly growing Jewish towns had approximately 10,000 members, continued to be subordinate to the civilian leadership of the Histadrut. The Histadrut also was responsible for the ———— 1 Michael Studemund-Halévy has dealt with the fascinating, complex personality of David Sealtiel/Shaltiel in a number of publications in German, Hebrew, French and English: “From Hamburg to Paris”; “Vom Shaliach in den Yishuv”; “Sioniste au par- fum romanesque”; “David Shaltiel.” See also [Shaltiel, David]. “In meines Vaters Haus”; Scholem. “Erinnerungen an David Shaltiel (1903–1968).” The short bio- graphical sketches on David Sealtiel are often based on inadequate, incorrect, wrong or fictitious informations: Avidar-Tschernovitz. -

Communal Commercial Check City of Aachen

Eigentum von Fahrländer Partner AG, Zürich Communal commercial check City of Aachen Location Commune Aachen (Code: 5334002) Location Aachen (PLZ: 52062) (FPRE: DE-05-000334) Commune type City District Städteregion Aachen District type District Federal state North Rhine-Westphalia Topics 1 Labour market 9 Accessibility and infrastructure 2 Key figures: Economy 10 Perspectives 2030 3 Branch structure and structural change 4 Key branches 5 Branch division comparison 6 Population 7 Taxes, income and purchasing power 8 Market rents and price levels Fahrländer Partner AG Communal commercial check: City of Aachen 3rd quarter 2021 Raumentwicklung Eigentum von Fahrländer Partner AG, Zürich Summary Macro location text commerce City of Aachen Aachen (PLZ: 52062) lies in the City of Aachen in the District Städteregion Aachen in the federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia. Aachen has a population of 248'960 inhabitants (31.12.2019), living in 142'724 households. Thus, the average number of persons per household is 1.74. The yearly average net migration between 2014 and 2019 for Städteregion Aachen is 1'364 persons. In comparison to national numbers, average migration tendencies can be observed in Aachen within this time span. According to Fahrländer Partner (FPRE), in 2018 approximately 34.3% of the resident households on municipality level belong to the upper social class (Germany: 31.5%), 33.6% of the households belong to the middle class (Germany: 35.3%) and 32.0% to the lower social class (Germany: 33.2%). The yearly purchasing power per inhabitant in 2020 and on the communal level amounts to 22'591 EUR, at the federal state level North Rhine-Westphalia to 23'445 EUR and on national level to 23'766 EUR. -

Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei

Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei By ©2016 Alison Miller Submitted to the graduate degree program in the History of Art and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Maki Kaneko ________________________________ Dr. Sherry Fowler ________________________________ Dr. David Cateforis ________________________________ Dr. John Pultz ________________________________ Dr. Akiko Takeyama Date Defended: April 15, 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Alison Miller certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Maki Kaneko Date approved: April 15, 2016 ii Abstract This dissertation examines the political significance of the image of the Japanese Empress Teimei (1884-1951) with a focus on issues of gender and class. During the first three decades of the twentieth century, Japanese society underwent significant changes in a short amount of time. After the intense modernizations of the late nineteenth century, the start of the twentieth century witnessed an increase in overseas militarism, turbulent domestic politics, an evolving middle class, and the expansion of roles for women to play outside the home. As such, the early decades of the twentieth century in Japan were a crucial period for the formation of modern ideas about femininity and womanhood. Before, during, and after the rule of her husband Emperor Taishō (1879-1926; r. 1912-1926), Empress Teimei held a highly public role, and was frequently seen in a variety of visual media. -

NORTH RHINE WESTPHALIA 10 REASONS YOU SHOULD VISIT in 2019 the Mini Guide

NORTH RHINE WESTPHALIA 10 REASONS YOU SHOULD VISIT IN 2019 The mini guide In association with Commercial Editor Olivia Lee Editor-in-Chief Lyn Hughes Art Director Graham Berridge Writer Marcel Krueger Managing Editor Tom Hawker Managing Director Tilly McAuliffe Publishing Director John Innes ([email protected]) Publisher Catriona Bolger ([email protected]) Commercial Manager Adam Lloyds ([email protected]) Copyright Wanderlust Publications Ltd 2019 Cover KölnKongress GmbH 2 www.nrw-tourism.com/highlights2019 NORTH RHINE-WESTPHALIA Welcome On hearing the name North Rhine- Westphalia, your first thought might be North Rhine Where and What? This colourful region of western Germany, bordering the Netherlands and Belgium, is perhaps better known by its iconic cities; Cologne, Düsseldorf, Bonn. But North Rhine-Westphalia has far more to offer than a smattering of famous names, including over 900 museums, thousands of kilometres of cycleways and a calendar of exciting events lined up for the coming year. ONLINE Over the next few pages INFO we offer just a handful of the Head to many reasons you should visit nrw-tourism.com in 2019. And with direct flights for more information across the UK taking less than 90 minutes, it’s the perfect destination to slip away to on a Friday and still be back in time for your Monday commute. Published by Olivia Lee Editor www.nrw-tourism.com/highlights2019 3 NORTH RHINE-WESTPHALIA DID YOU KNOW? Despite being landlocked, North Rhine-Westphalia has over 1,500km of rivers, 360km of canals and more than 200 lakes. ‘Father Rhine’ weaves 226km through the state, from Bad Honnef in the south to Kleve in the north. -

Isabelle Dolezalek Arabic Script on Christian Kings Das Mittelalter Perspektiven Mediävistischer Forschung

Isabelle Dolezalek Arabic Script on Christian Kings Das Mittelalter Perspektiven mediävistischer Forschung Beihefte Herausgegeben von Ingrid Baumgärtner, Stephan Conermann und Thomas Honegger Band 5 Isabelle Dolezalek Arabic Script on Christian Kings Textile Inscriptions on Royal Garments from Norman Sicily Gedruckt mit freundlicher Unterstützung der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) ISBN 978-3-11-053202-9 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-053387-3 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-053212-8 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Typesetting: Satzstudio Borngräber, Dessau-Roßlau Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Gedruckt auf säurefreiem Papier Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Contents Preface — IX Introduction — XI Chapter I Shaping Perceptions: Reading and Interpreting the Norman Arabic Textile Inscriptions — 1 1 Arabic-Inscribed Textiles from Norman and Hohenstaufen Sicily — 2 2 Inscribed Textiles and Arabic Inscriptions in European Medieval Arts — 43 3 Historical Receptions of the Ceremonial Garments from Norman Sicily — 51 4 Approaches to Arabic Inscriptions in European Medieval Arts: Methodological Considerations — 64 Chapter II An Imported Ornament? Comparing the Functions -

Lernen Von Vauban. Ein Studienprojekt Und Mehr…

PT_Materialien 32 Lernen von Vauban. Ein Studienprojekt und mehr… vorgelegt von Ulrike Sommer und Carolin Wiechert Frontbild: Selle, Klaus (2013); Aufnahmen während der Exkursionen nach Vauban; innerhalb des Projektes M2.1, Von Vauban Lernen. Aachen Lernen von Vauban. Ein Studienprojekt und mehr… Durchgeführt von Studierenden an der Fakultät für Architektur der RWTH Aachen University im Rahmen eines studentischen Projektes. Die Ergebnisse wurden zusammengestellt von Dipl.-Ing., M.Sc- Ulrike Sommer und M.Sc. Carolin Wiechert RWTH Aachen University Lehrstuhl für Planungstheorie und Stadtentwicklung Layout: Carolin Wiechert Aachen, im Februar 2014 Inhalt Vorwort 8 Lernen von Vauban. Ein Studienprojekt und mehr… 8 1. Zur Einführung 13 Das Quartier Vauban 13 Akteure 14 Städtebauliche Struktur 17 Verkehrskonzept 18 2. Methodisches Vorgehen 22 3. Die sechs Zieldimensionen und weitere Erkenntnisse 25 3.1 Städtebauliche Struktur 25 Stadt der kurzen Wege 25 Parzellierung und Baustrukturen 31 Urbane Dichte 33 Verknüpfung mit dem Naherholungsgebiet und der Nachbargemeinde 35 Bestandserhalt 36 Fazit Städtebauliche Struktur 37 3.2 Wohnen 38 Wohnraumversorgung und Art der Bebauung 38 Bauen in selbstorganisierten Gruppen 44 Fazit Wohnen 46 3.3 Bevölkerung, Soziales 46 Preiswerter, öffentlich geförderter Wohnungsbau 46 Soziale Durchmischung 49 Infrastruktur für Familien 51 Nachbarschaften 52 Fazit Bevölkerung, Soziales 54 Lernen von Vauban. Ein Studienprojekt und mehr... 3.4 Mobilität 54 Verkehrsberuhigung 54 ÖPNV- Anbindung 65 Fußgänger und Radverkehr 68 Wohnen ohne Auto 72 Fazit Mobilität 78 3.5 Umwelt 79 Energie 79 Entwässerung 85 Lärm 88 Vegetation 91 Fazit Umwelt 94 3.6 Prozess 95 Erweiterte Bürgerbeteiligung und lernende Planung 95 Fazit Prozess 101 3.7 Weitere Erkenntnisse 102 Älter werden in Vauban 102 Konflikte unter den Bewohnern in Vauban 103 Infrastruktur für Besucher 104 4. -

From Charlemagne to Hitler: the Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire and Its Symbolism

From Charlemagne to Hitler: The Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire and its Symbolism Dagmar Paulus (University College London) [email protected] 2 The fabled Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire is a striking visual image of political power whose symbolism influenced political discourse in the German-speaking lands over centuries. Together with other artefacts such as the Holy Lance or the Imperial Orb and Sword, the crown was part of the so-called Imperial Regalia, a collection of sacred objects that connotated royal authority and which were used at the coronations of kings and emperors during the Middle Ages and beyond. But even after the end of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, the crown remained a powerful political symbol. In Germany, it was seen as the very embodiment of the Reichsidee, the concept or notion of the German Empire, which shaped the political landscape of Germany right up to National Socialism. In this paper, I will first present the crown itself as well as the political and religious connotations it carries. I will then move on to demonstrate how its symbolism was appropriated during the Second German Empire from 1871 onwards, and later by the Nazis in the so-called Third Reich, in order to legitimise political authority. I The crown, as part of the Regalia, had a symbolic and representational function that can be difficult for us to imagine today. On the one hand, it stood of course for royal authority. During coronations, the Regalia marked and established the transfer of authority from one ruler to his successor, ensuring continuity amidst the change that took place. -

The Developmentof Early Imperial Dress from the Tetrachs to The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. The Development of Early Imperial Dress from the Tetrarchs to the Herakleian Dynasty General Introduction The emperor, as head of state, was the most important and powerful individual in the land; his official portraits and to a lesser extent those of the empress were depicted throughout the realm. His image occurred most frequently on small items issued by government officials such as coins, market weights, seals, imperial standards, medallions displayed beside new consuls, and even on the inkwells of public officials. As a sign of their loyalty, his portrait sometimes appeared on the patches sown on his supporters’ garments, embossed on their shields and armour or even embellishing their jewelry. Among more expensive forms of art, the emperor’s portrait appeared in illuminated manuscripts, mosaics, and wall paintings such as murals and donor portraits. Several types of statues bore his likeness, including those worshiped as part of the imperial cult, examples erected by public 1 officials, and individual or family groupings placed in buildings, gardens and even harbours at the emperor’s personal expense. -

Evidence from Hamburg's Import Trade, Eightee

Economic History Working Papers No: 266/2017 Great divergence, consumer revolution and the reorganization of textile markets: Evidence from Hamburg’s import trade, eighteenth century Ulrich Pfister Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster Economic History Department, London School of Economics and Political Science, Houghton Street, London, WC2A 2AE, London, UK. T: +44 (0) 20 7955 7084. F: +44 (0) 20 7955 7730 LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC HISTORY WORKING PAPERS NO. 266 – AUGUST 2017 Great divergence, consumer revolution and the reorganization of textile markets: Evidence from Hamburg’s import trade, eighteenth century Ulrich Pfister Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster Email: [email protected] Abstract The study combines information on some 180,000 import declarations for 36 years in 1733–1798 with published prices for forty-odd commodities to produce aggregate and commodity specific estimates of import quantities in Hamburg’s overseas trade. In order to explain the trajectory of imports of specific commodities estimates of simple import demand functions are carried out. Since Hamburg constituted the principal German sea port already at that time, information on its imports can be used to derive tentative statements on the aggregate evolution of Germany’s foreign trade. The main results are as follows: Import quantities grew at an average rate of at least 0.7 per cent between 1736 and 1794, which is a bit faster than the increase of population and GDP, implying an increase in openness. Relative import prices did not fall, which suggests that innovations in transport technology and improvement of business practices played no role in overseas trade growth. -

VIVERE MILITARE EST from Populus to Emperors - Living on the Frontier Volume I

VIVERE MILITARE EST From Populus to Emperors - Living on the Frontier Volume I BELGRADE 2018 VIVERE MILITARE EST From Populus to Emperors - Living on the Frontier INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY MONOGRAPHIES No. 68/1 VIVERE MILITARE EST From Populus to Emperors - Living on the Frontier VOM LU E I Belgrade 2018 PUBLISHER PROOFREADING Institute of Archaeology Dave Calcutt Kneza Mihaila 35/IV Ranko Bugarski 11000 Belgrade Jelena Vitezović http://www.ai.ac.rs Tamara Rodwell-Jovanović [email protected] Rajka Marinković Tel. +381 11 2637-191 GRAPHIC DESIGN MONOGRAPHIES 68/1 Nemanja Mrđić EDITOR IN CHIEF PRINTED BY Miomir Korać DigitalArt Beograd Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade PRINTED IN EDITORS 500 copies Snežana Golubović Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade COVER PAGE Nemanja Mrđić Tabula Traiana, Iron Gate Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade REVIEWERS EDITORiaL BOARD Diliana Angelova, Departments of History of Art Bojan Ðurić, University of Ljubljana, Faculty and History Berkeley University, Berkeley; Vesna of Arts, Ljubljana; Cristian Gazdac, Faculty of Dimitrijević, Faculty of Philosophy, University History and Philosophy University of Cluj-Napoca of Belgrade, Belgrade; Erik Hrnčiarik, Faculty of and Visiting Fellow at the University of Oxford; Philosophy and Arts, Trnava University, Trnava; Gordana Jeremić, Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade; Kristina Jelinčić Vučković, Institute of Archaeology, Miomir Korać, Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade; Zagreb; Mario Novak, Institute for Anthropological Ioan Piso, Faculty of History and Philosophy Research, -

CENTRE CHARLEMAGNE GB Neues Stadtmuseum Aachen

CENTRE CHARLEMAGNE GB Neues Stadtmuseum Aachen ROUTECHARLEMAGNEAACHEN Contents Route Charlemagne 3 The building and its history 4 Where the pillory once stood Permanent exhibition 6 Celts, spa guests, Charlemagne Prize 6 Flintstone and hot springs 8 Charlemagne takes up residence in Aachen 10 What the Palace looked like 12 The city of coronations 14 The Great Town Fire 15 A spa taxi for the nobility 16 The French in Aachen 18 Cloth and needles 19 From frontline town to European city 20 Service 22 Information 23 Imprint 24 2 Centre Charlemagne – Neues Stadtmuseum Aachen Route Charlemagne Aachen’s Route Charlemagne connects significant locations around the city to create a path through history leading from the past into the future. At the centre of the Route Charlemagne is the former palace complex of Charlemagne, with the Town Hall, the Katschhof and the Cathedral – once the focal point of an empire of European proportions. Aachen is a historical town, a centre of science, and a European city whose story can be seen as a history of Europe. This and other major themes like religion, power and media are reflected and explored in places like the Cathedral and the Town Hall, the International News - paper Museum, the Grashaus, the Couven Museum, the SuperC of the RWTH Aachen University and the Elisenbrunnen. The central starting point of the Route Charlemagne is the “Centre Charlemagne – New City Museum Aachen”, located on the Katschhof between the Town Hall and the Cathedral. Here, visitors can get infor- mation on all the sights along the Route Charlemagne. A three-cornered museum Why does the triangle play such an important role in the Centre Char- lemagne? The answer is simple: the architects drew inspiration from an urban peculiarity of Aachen. -

Gender-Bending Regalia in the Tomb of Constance of Aragon, Queen of Hungary and Sicily

2018 V From Her Head to Her Toes: Gender-Bending Regalia in the Tomb of Constance of Aragon, Queen of Hungary and Sicily Christopher Mielke Article: From Her Head to Her Toes: Gender-Bending Regalia in the Tomb of Constance of Aragon, Queen of Hungary and Sicily From Her Head to Her Toes: Gender-Bending Regalia in the Tomb of Constance of Aragon, Queen of Hungary and Sicily Christopher Mielke INDEPENDENT SCHOLAR Abstract: This article re-examines József Deér’s claim that the crown uncovered in the tomb of Constance of Aragon (d. 1222) was originally her husband’s. His argument is based entirely on the shape of the crown itself, and ignores the context of her burial and the other idiosyncrasies of Frederick II’s burial provisions at Palermo Cathedral. By examining the contents of the grave of Constance, and by discussing patterns related to the size of medieval crowns recovered from archaeological context, the evidence indicates that this crown would have originally adorned the buried queen’s head. Rather than identifying it as a ‘male’ crown that found its way into the queen’s sarcophagus as a gift from her husband, this article argues that Constance’s crown is evidence that as a category of analysis, gender is not as simple as it may appear. In fact, medieval crowns often had multiple owners and sometimes a crown could be owned, or even worn, by someone who had a different gender than the original owner. This fact demonstrates the need for a more complex, nuanced interpretation of regalia found in an archaeological context.