Chapter 2 “Ben Azzai's Central Principle”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A USER's MANUAL Part 1: How Is Halakhah Organized?

TORAHLEADERSHIP.ORG RABBI ARYEH KLAPPER HALAKHAH: A USER’S MANUAL Part 1: How is Halakhah Organized? I. How is Halakhah Organized? 4 case studies a. Mishnah Berakhot 1:1, and gemara thereupon b. Support of the poor Peiah, Bava Batra, Matnot Aniyyim, Yoreh Deah) c. Conversion ?, Yevamot, Issurei Biah, Yoreh Deah) d. Mourning Moed Qattan, Shoftim, Yoreh Deiah) Mishnah Berakhot 1:1 From what time may one recite the Shema in the evening? From the hour that the kohanim enter to eat their terumah Until the end of the first watch, in the opinion of Rabbi Eliezer. The Sages say: Until midnight. Rabban Gamliel says: Until morning. It happened that his sons came from a wedding feast. They said to him: We have not yet recited the Shema. He said to them: If it has not yet morned, you are obligated to recite it. Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 2a What is the context of the Mishnah’s opening “From when”? Also, why does it teach about the evening first, rather than about the morning? The context is Scripture saying “when you lie down and when you arise” (Devarim 6:7, 11:9). what the Mishnah intends is: “The time of the Shema of lying-down – when is it?” Alternatively: The context is Creation, as Scripture writes “There was evening and there was morning”. Mishnah Berakhot 1:1 (continued) Not only this – rather, everything about which the Sages say until midnight – their mitzvah is until morning. The burning of fats and organs – their mitzvah is until morning. All sacrifices that must be eaten in a day – their mitzvah is until morning. -

The Fundamental Principle of the Torah

The Fundamental Principle of the Torah Rabbi David Horwitz Rosh Yeshiva, RIETS The Sifra, that is, Torat Kohanim, Midrash Halakhah on Sefer Va-Yiqra quotes a celebrated dispute between the Tannaitic authorities R. Akiba and Ben Azzai. לא תקם ולא תטר את בני עמך ואהבת לרעך You shall not take vengeance or bear a grudge against כמוך אני ה' your kinfolk. Love your neighbor as yourself: I am the ויקרא יט:יח L-RD Leviticus 19:18 ואהבת לרעך כמוך, רבי עקיבא אומר Love your neighbor as yourself: R. Akiba states, this is a great זה כלל גדול בתורה, בן עזאי אומר זה principle of the Torah. Ben Azzai states: This is the book of the ספר תולדות אדם, זה כלל גדול מזה. descendants of Adam (Genesis 5:1): This is even a greater ספרא קדושים פרשה ב ד"ה פרק ד .principle Sifra, on Sefer Va-Yiqra (ad loc.) This dispute is cited, among other places, in the Talmud Yerushalmi to the tractate Nedarim as well. The mishnah discusses methods of retroactively nullifying vows by exposing the fact that there are changed circumstances that make nullification admissible. Some of these changed circumstances can consist of realization of the full import of the Torah’s interpersonal commandments. Regarding one who had vowed that another could not have any benefit from him, the mishnah states: ועוד אמר ר"מ: פותחין לו מן הכתוב In addition, R. Meir said, one “opens” (the way to retroactively שבתורה, ואומרין לו: אילו היית nullify a vow) for him with what is written in the Torah. -

Hemdat Yamim Korach

Korach Korach, 21 Sivan 5776 Post-Modernism in Ancient Times and Today Harav Yosef Carmel We will discuss those who Israelis call elitot (members of the “elite” class), who have been championing a spiritual trend in which the individual is at the center, and religious, ethnic, or national groups take a backseat. Personal rights overcome obligations to the public, and individuality is not just part of the mosaic of society but has the power of “for me the world was created.” For such people, irrefutable authority, whether political or spiritual, is foreign, which explains a lot of what we see. In the past few parshiyot , different people have challenged Moshe’s leadership. Eldad and Meidad prophesied in the encampment without Moshe’s permission. Yehoshua wanted to take action against them (Bamidbar 11:28), but Moshe refused: “If only the entire nation of Hashem could be prophets, that Hashem would place His spirit upon them” (ibid. 29). In our parasha , Korach openly opposed Moshe. He was an elitist, as Chazal said that he was a great scholar and one of the people who carried the Holy Ark (Bamidbar Rabba 18:3). The Torah also describes his 250 associates as part of the elite of society ( kri’ei moed, anshei shem – Bamidbar 16:2; see Sanhedrin 110a). They all complained that since the entire congregation is holy, there is no excuse for Moshe and Aharon to exert such control. “Everyone has the ability to lead himself”! In this case, Moshe’s reacted very differently, setting a showdown intended to doom the losers to death. -

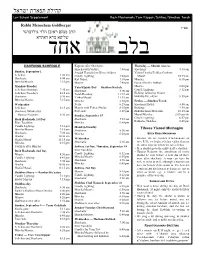

קהילת תפארת ישראל ����Lev Echad Supplement / ��� ������ ��-����Rosh Hashanah/Yom ���� Kippur/Sukkos/Simchasbwelcome to Torah

קהילת תפארת ישראל Lev Echad Supplement / -Rosh Hashanah/Yom Kippur/Sukkos/SimchasbWelcome to Torah CongregationRabbi Menachem Tiferes Goldberger Yisroel! Parshas Tazria/Metzora בס״ד Rabbi Goldberger Shiurim הרב מנחם ראובן הלוי גולדברגר Rabbi Goldberger has resumed his afternoon shiur for men and women. We will be studying the Haggada ,שליטא Mincha מרא hour beforeדאתרא On Shabbos, one shel Pesach with commentaries. Yankelove in Lakewood, NJ. בלב אחד DAVENING SCHEDULE Kaparos after Shacharis: Thursday — Shmini Atzeres Mincha with Viduyi: 4:00 pm Shacharis: 8:30 am Sunday, September 1 Seudah Hamafsekes/Bless children Yizkor/Drasha/Tefillas Geshem/ Selichos: 1:00 am Candle Lighting: 7:00 pm Musaf: 10:45 am Shacharis: 8:00 am Kol Nidrei: 7:10 pm Mincha: 6:10 pm Mincha/Maariv: 7:15 pm Maariv: 7:40 pm Farewell to the Sukkah Maariv: 8:00 pm Monday-Tuesday Yom Kippur Day — Shabbos Kodesh Candle Lighting: 8:12 pm Selichos (Monday): 7:45 am Shacharis: 8:00 am Bidding following Maariv Selichos (Tuesday): 6:10 am Torah Reading: 11:15 am Hakafos/five aliyos: 8:50 pm Shacharis: 6:30 am Yizkor/Musaf: 11:45 am Mincha/Maariv: 7:15 pm Mincha: 4:50 pm Friday — Simchas Torah Wednesday Neila: 6:25 pm Shacharis/Hallel: 8:00 am Selichos: 5:15 am Maariv with Tekias Shofar: 8:15 pm Bidding: 9:30 am Shacharis followed by Fast ends: 8:29 pm Hakafos/Krias HaTorah: 10:15 am Musaf/Mincha: 2:00 pm ish Hataras Nedarim: 6:30 am Sunday, September 15 Candle Lighting: 6:37 pm Rosh Hashanah, 1st Day Shacharis: 7:55 am Kabbalas Shabbos: 6:40 pm Eruv Tavshilin Mincha: 6:50 pm Candle Lighting: 7:14 pm Monday-Tuesday Tiferes Yisroel Minhagim Mincha/Maariv: 7:15 pm Shacharis: 6:30 am Shacharis: 7:30 am Mincha: 6:50 pm EREV ROSH HASHANAH Drasha: 10:30 am Because we are marbeh b’tachanunim on Shofar/Musaf: 11:15 am Wednesday • erev R”H, we begin selichos earlier than on Mincha: 6:15 pm Shacharis: 6:30 am the other days on which we say selichos. -

Derech Hateva 2018.Pub

Derech HaTeva A Journal of Torah and Science A Publication of Yeshiva University, Stern College for Women Volume 22 2017-2018 Co-Editors Elana Apfelbaum | Tehilla Berger | Hannah Piskun Cover & Layout Design Shmuel Ormianer Printing Advanced Copy Center, Brooklyn, NY 11230 Acknowledgements The editors of this year’s volume would like to thank Dr. Harvey Babich for the incessant time and effort that he devotes to this journal. Dr. Babich infuses his students with a passion for the Torah Umadda vision and serves as an exemplar of this philosophy to them. Through his constant encouragement and support, students feel confident to challenge themselves and find interesting connections between science and Torah. Dr. Babich, thank you for all the effort you contin- uously devote to us through this journal, as well as to our personal and future lives as professionals and members of the Jewish community. The publication of Volume 22 of this journal was made possible thanks to the generosity of the following donors: Dr. and Mrs. Harvey Babich Mr. and Mrs. Louis Goldberg Dr. Fred and Dr. Sheri (Rosenfeld) Grunseid Rabbi and Mrs. Baruch Solnica Rabbi Joel and Dr. Miriam Grossman Torah Activities Council YU Undergraduate Admissions We thank you for making this opportunity possible. Elana Apfelbaum Tehilla Berger Hannah Piskun Dedication We would like to dedicate the 22nd volume of Derech HaTeva: A Journal of Torah and Science to the soldiers of the Israel Defence Forces (IDF). Formed from the ashes of the Holocaust, the Israeli army represents the enduring strength and bravery of the Jewish people. The soldiers of the IDF have risked their lives to protect the Jewish nation from adversaries in every generation in wars such as the Six-Day War and the Yom Kippur War. -

Download File

Halevy, Halivni and The Oral Formation of the Babylonian Talmud Ari Bergmann Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Ari Bergmann All rights reserved ABSTRACT Halevy, Halivni and The Oral Formation of the Babylonian Talmud Ari Bergmann This dissertation is dedicated to a detailed analysis and comparison of the theories on the process of the formation of the Babylonian Talmud by Yitzhak Isaac Halevy and David Weiss Halivni. These two scholars exhibited a similar mastery of the talmudic corpus and were able to combine the roles of historian and literary critic to provide a full construct of the formation of the Bavli with supporting internal evidence to support their claims. However, their historical construct and findings are diametrically opposed. Yitzhak Isaac Halevy presented a comprehensive theory of the process of the formation of the Talmud in his magnum opus Dorot Harishonim. The scope of his work was unprecedented and his construct on the formation of the Talmud encompassed the entire process of the formation of the Bavli, from the Amoraim in the 4th century to the end of the saboraic era (which he argued closed in the end of the 6th century). Halevy was the ultimate guardian of tradition and argued that the process of the formation of the Bavli took place entirely within the amoraic academy by a highly structured and coordinated process and was sealed by an international rabbinical assembly. While Halevy was primarily a historian, David Weiss Halivni is primarily a talmudist and commentator on the Talmud itself. -

Nedarim (Vows): Obligation and Annulment by David Silverberg Part

Nedarim (Vows): Obligation and Annulment By David Silverberg Part 1 – Nidrei Issur & Nidrei Hekdesh Parashat Matot opens with the laws concerning nedarim – voluntary obligations a person takes upon himself on oath. The Torah very clearly obligates one to abide by such vows: "A man who makes a vow to the Lord, or swears on oath to impose a prohibition upon himself, shall not violate his word; he shall act in accordance with everything that left his mouth" (30:3). The Torah returns to the issue of vows later, in the Book of Devarim (23:22-4): “If you make a vow to the Lord your God, do not delay in paying it, for the Lord your God will assuredly claim it from you, and you shall bear iniquity… You must observe and carry out that which leaves your mouth, as you voluntarily vowed to the Lord your God, as you spoke with your mouth.” Although both these sections – in Parashat Matot, and in Devarim – discuss the obligation to act upon one's voluntary commitments, a clear distinction exists between the two contexts. Here, in Parashat Matot, the Torah speaks of a vow whereby one seeks "to impose a prohibition on himself." The most common example given in Talmudic discussions of nedarim is one who vows to abstain from a given type of food. In Devarim, the Torah warns against delaying "payment" (" lo te'acher le- shalemo "), clearly referring to a donation pledge, rather than a vow of abstinence. Indeed, the Sifrei interprets the verses in Devarim as requiring one to fulfill voluntary commitments involving all types of sacred donations, including sacrificial offerings, donations to the Temple treasury, and even charitable contributions. -

Rabbis on the Road: Exposition En Route in Classical Rabbinic Texts

Rabbis on the Road: Exposition En Route in Classical Rabbinic Texts by Ruth Ellen Haber A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the Graduate Theological Union in Jewish Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Daniel Boyarin, chair Professor Dina Stein Professor Michael Nylan Fall 2014 Abstract Rabbis on the Road: Exposition En Route in Classical Rabbinic Texts by Ruth Ellen Haber Joint Doctor of Philosophy in Jewish Studies with the Graduate Theological Union University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel Boyarin, Chair Throughout classical rabbinic texts, we find accounts of sages expounding Scripture or law, while “walking on the road.” We may well wonder why we find these sages in transit, rather than in the usual sites of Torah study, such as the bet midrash (study house) or ʿaliyah (upper story of a home). Indeed, in this corpus of texts, sages normally sit to study; the two acts are so closely associated, that the very word “sitting” is synonymous with a study session or academy. Moreover, throughout the corpus, “the road” is marked as the site of danger, disruption and death. Why then do these texts tell stories of sages expounding en route? In seeking out the rabbinic road, I find that, against these texts’ pervasive notion of travel danger runs another, competing motif: the road as the proper – even necessary – site of Torah study. Tracing the genealogy of the road exposition (or “road derasha”), I find it rooted in traditional Wisdom texts, which have been adapted to form a new, “literal” metaphor. -

The Ethical Impulse in Rabbinic Judaism Rabbi Dr Elliot N

4329-ZIG-Walking with Justice:Cover 5/22/08 3:27 PM Page 1 The Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies esmc lkv,vk Walking with Justice Edited By Rabbi Bradley Shavit Artson and Deborah Silver ogb hfrs vhfrs 4329-ZIG-Walking with Justice:4329-ZIG-Walking with Justice 5/23/08 9:56 AM Page 30 THE ETHICAL IMPULSE IN RABBINIC JUDAISM RABBI DR ELLIOT N. DORFF FOUNDATIONS IN HISTORY AND PHILOSOPHY Although the Bible (especially its first five books, the Torah) is critically important in defining what Judaism stands for, it is the Rabbis of the Mishnah, Talmud, and Midrash (the “classical Rabbis”) and subsequently the rabbis in the many centuries since the close of the Talmud (c. 500 C.E.) who determined what that scripture was to mean for Jews in both belief and action (in contrast to how Karaites, secular Jews, Christians, Muslims, modern biblical scholars, and all others interpret the Bible). Judaism, in other words, is the religion of the rabbis even more than it is the religion of the Bible, just as American law is more what American judges and legislators have created in interpreting and applying the United States Constitution than it is the Constitution itself. To understand how Judaism understands ethics, then, one must study how the Rabbis understood and applied ethics. Rabbis throughout the ages, however, did not speak with one voice. On the contrary, rabbinic Judaism, like its biblical predecessor, is a very feisty religion, one that takes joy in people arguing with each other and even with God. This means that any author reflecting on any aspect of Judaism will be providing a Jewish understanding of the topic, not “the Jewish understanding” of it or “what Judaism says” about it.1 Still, with all the variations among the rabbis, one can locate some concepts and values that most, if not all, scholars would agree are central to the Rabbinic mind and heart. -

Derech Hateva 2019

Derech HaTeva A Journal of Torah and Science A Publication of Yeshiva University Stern College for Women Volume 23 2018-2019 Editors Elana Apfelbaum | Tehilla Berger Co-Editors Shani Kahan | Tamar Schwartz Cover Design Deborah Coopersmith Layout Design Shmuel Ormianer Printing Advanced Copy Center, Brooklyn, NY 11230 Acknowledgements Appreciation is expressed to Dr. Babich for developing and overseeing the publication, Derech HaTeva. A Journal of Torah and Science, to be a literary vehicle for students of Stern College for Women to utilize their dual strengths – Torah UMadda. Dr. Babich infuses his students with a passion for the Torah Umadda approach. This journal is a conduit to accomplishing just that, as throughout the research process, students feel confident to build bridges between Torah and science. Thank you, Dr. Babich, for your continuous support of us and the student body as a whole. The publication of Volume 23 of this journal was made possible thanks to the generosity of the following donors: Dr. Harvey and Mrs. Marsha Babich Rabbi Joel and Dr. Miriam Grossman Dr. Fred and Dr. Sheri (Rosenfeld) Grunseid Dr. Richard and Mrs. Helen Schwimmer Rabbi Baruch and Mrs. Rosette Solnica Torah Activities Council YU Undergraduate Admissions We thank you for making this opportunity possible. Editors: Elana Apfelbaum Tehilla Berger Co-Editors Shani Kahan Tamar Schwartz Dedication On Motzei Shabbos, October 17th 2018, our community was left bewildered as we learned about the horrific massacre in the Tree of Life Or L'Simcha congregation, Pittsburgh, PA. When eleven precious souls of our own were ruthlessly torn from our nation, in an unprecedented act of antisemitism in the United States, we can only find some sense of solace in turning to God. -

Vol 6 the Laws of Foods Forbidden Due to Potential Danger Introduction 23 Eating Fish and Meat Together 24 How to Separate Betwe

Vol 6 The Laws of Foods Forbidden Due to Potential Danger Introduction 23 Eating Fish and Meat Together 24 How to Separate Between Fish and Meat 25 Cooking Fish and Meat in the Same Oven 26 Cooking Fish in a Meat Pot 27 Are Chicken and Fish Also Forbidden? 29 Is a Mixture of Fish and Meat Still Dangerous? 30 Bitul B’shishim for a Mixture of Fish and Meat 31 Eating Fish With Dairy 33 Uncovered Liquids 37 Other Foods Forbidden Due to Danger 42 Foods Placed Underneath a Bed 42 Leaving Peeled Eggs, Onions and Garlic out Overnight 45 Summary of the Laws of Foods Forbidden Due to Potential Danger 48 Halachic Perspectives on the Coronavirus I What to Do When Plagues Strike? 55 What If It Is Not One’s Time to Die? 61 Medical Professionals 66 Further Iyun: Balancing Risk and Reward: A Halachic Perspective on Societal Restrictions and COVID-19 68 The Laws of Kashrut of Selected Ingredients and Non-Food Products The Kashrut of Medicine 79 Consumption in an Unusual Manner and Unpleasant Tasting Medicine 79 Pleasant-Tasting Medicine 82 The Kashrut of Toothpaste 87 The Kashrut of Honey and Related Products 92 Honey 92 Royal Jelly 94 Beeswax 98 The Kashrut of Shellac, Confectioner’s Glaze, and Waxed Fruits and Vegetables 100 The Kashrut of Gelatin 105 Summary of the Laws of Kashrut of Raw Ingredients 113 Further Iyun: Is Whisky Kosher? 117 Responsa 121 The Laws of Chinuch for Children The Basis and Scope of the Mitzva of Chinuch 127 Is the Mitzva of Chinuch De’oraita or Derabanan? 128 The Mitzva of Chinuch Regarding the Mother 129 The Mitzva of Chinuch -

Index of Names and Works

Index of Names and Works Abaye , 80-82 Bible, x, xi-xii, 2-3, 6-8,47-71, 84, Abed-nego, 64 101 ' 132, 133-36, 148-50 Abraham, 87 Bilu, Yoram , 73n, 148 Abraham , Karl, 15n, 29n, 102n, 12ln, Binswanger, Ludwig, 2ln, 31 , 141 13ln Birdsey, Bruce, 86n Ackerman, James S., 52n Blatt , DavidS., In, 141 Adler, Alfred, 31-33, 98n , 140 Bloom, Harold, ix-x, xii, 6, 128-29, Akiba, R., 83n 141 Albeck, Chanoch, 57n, 147 Blumenthal, David, 86n, 123n Alberti , Leon Battista, 35 Boss, Menard, 22n, 141 Alexander, 117 Bossard, Robert, 115n , 141 Almoli, Solomon, 9ln Boyarin, Daniel, xii Alter, Robert, 6n, 52n , 70n, 148 Brenkman, John, 26n Anzieu , Didier, lin, 13n, 116n, 12ln, Breuer, Josef, 13, 19, 41 140 Brisman, Leslie , xii Aristander, 117 Brown, Ronald N., 83n, 148 Aristotle, 5, 17, 95 , 98n, 140 Buber, Martin, 70n, 148 Aron, Willy, 2n , 140 Budick, Sanford, 5n, 7n , 149 Artemidorus, 5, 17-20, 117 , 140 Aue , Maximilian, 123n Cappadocia, 85, 118, 131 Casey, Edward, xii Babylonia, 64, 70 Charles, R. H. , 60n, 148 Bakan, David, In , 74n, 140 Childs, Brevard, xii Baldwin, Joyce, 66n, 148 Chisda, R., 75-76, 80 Balkanyi , Charlotte, 36n , 140 Clermont-Ganneau, Charles, 67n, 148 Bally, Charles, 98n-99n Cohen, Abraham, 74n, 148 Bana'ah , R., 78-79, 92 Cohen, B., 73n, 148 Bar Hedia, 79-82, 86-87, 91-93, 135 Cracow, 101-2 Bar Kappara, 83 Cuddihy, John Murray, In, 30n, 43n, Barrett, Cyril, 24n 127n, 141 Beck, Aaron T. , 33n , 140 Bein , Alex , 120n Dalbiez, Roland, 28n, 141 Belshazzar, 59, 66-68 Damstra, Martin, N., 106n, 141 Berakhot.