Nedarim (Vows): Obligation and Annulment by David Silverberg Part

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jewish Perspectives on Reproductive Realities by Rabbi Lori Koffman, NCJW Board Director and Chair of NCJW’S Reproductive Health, Rights and Justice Initiative

Jewish Perspectives on Reproductive Realities By Rabbi Lori Koffman, NCJW Board Director and Chair of NCJW’s Reproductive Health, Rights and Justice Initiative A note on the content below: We acknowledge that this document invokes heavily gendered language due to the prevailing historic male voices in Jewish rabbinic and biblical perspectives, and the fact that Hebrew (the language in which these laws originated) is a gendered language. We also recognize some of these perspectives might be in contradiction with one another and with some of NCJW’s approaches to the issues of reproductive health, rights, and justice. Background Family planning has been discussed in Judaism for several thousand years. From the earliest of the ‘sages’ until today, a range of opinions has existed — opinions which can be in tension with one another and are constantly evolving. Historically these discussions have assumed that sexual intimacy happens within the framework of heterosexual marriage. A few fundamental Jewish tenets underlie any discussion of Jewish views on reproductive realities. • Protecting an existing life is paramount, even when it means a Jew must violate the most sacred laws.1 • Judaism is decidedly ‘pro-natalist,’ and strongly encourages having children. The duty of procreation is based on one of the earliest and often repeated obligations of the Torah, ‘pru u’rvu’, 2 to be ‘fruitful and multiply.’ This fundamental obligation in the Jewish tradition is technically considered only to apply to males. Of course, Jewish attitudes toward procreation have not been shaped by Jewish law alone, but have been influenced by the historic communal trauma (such as the Holocaust) and the subsequent yearning of some Jews to rebuild community through Jewish population growth. -

A USER's MANUAL Part 1: How Is Halakhah Organized?

TORAHLEADERSHIP.ORG RABBI ARYEH KLAPPER HALAKHAH: A USER’S MANUAL Part 1: How is Halakhah Organized? I. How is Halakhah Organized? 4 case studies a. Mishnah Berakhot 1:1, and gemara thereupon b. Support of the poor Peiah, Bava Batra, Matnot Aniyyim, Yoreh Deah) c. Conversion ?, Yevamot, Issurei Biah, Yoreh Deah) d. Mourning Moed Qattan, Shoftim, Yoreh Deiah) Mishnah Berakhot 1:1 From what time may one recite the Shema in the evening? From the hour that the kohanim enter to eat their terumah Until the end of the first watch, in the opinion of Rabbi Eliezer. The Sages say: Until midnight. Rabban Gamliel says: Until morning. It happened that his sons came from a wedding feast. They said to him: We have not yet recited the Shema. He said to them: If it has not yet morned, you are obligated to recite it. Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 2a What is the context of the Mishnah’s opening “From when”? Also, why does it teach about the evening first, rather than about the morning? The context is Scripture saying “when you lie down and when you arise” (Devarim 6:7, 11:9). what the Mishnah intends is: “The time of the Shema of lying-down – when is it?” Alternatively: The context is Creation, as Scripture writes “There was evening and there was morning”. Mishnah Berakhot 1:1 (continued) Not only this – rather, everything about which the Sages say until midnight – their mitzvah is until morning. The burning of fats and organs – their mitzvah is until morning. All sacrifices that must be eaten in a day – their mitzvah is until morning. -

The Fundamental Principle of the Torah

The Fundamental Principle of the Torah Rabbi David Horwitz Rosh Yeshiva, RIETS The Sifra, that is, Torat Kohanim, Midrash Halakhah on Sefer Va-Yiqra quotes a celebrated dispute between the Tannaitic authorities R. Akiba and Ben Azzai. לא תקם ולא תטר את בני עמך ואהבת לרעך You shall not take vengeance or bear a grudge against כמוך אני ה' your kinfolk. Love your neighbor as yourself: I am the ויקרא יט:יח L-RD Leviticus 19:18 ואהבת לרעך כמוך, רבי עקיבא אומר Love your neighbor as yourself: R. Akiba states, this is a great זה כלל גדול בתורה, בן עזאי אומר זה principle of the Torah. Ben Azzai states: This is the book of the ספר תולדות אדם, זה כלל גדול מזה. descendants of Adam (Genesis 5:1): This is even a greater ספרא קדושים פרשה ב ד"ה פרק ד .principle Sifra, on Sefer Va-Yiqra (ad loc.) This dispute is cited, among other places, in the Talmud Yerushalmi to the tractate Nedarim as well. The mishnah discusses methods of retroactively nullifying vows by exposing the fact that there are changed circumstances that make nullification admissible. Some of these changed circumstances can consist of realization of the full import of the Torah’s interpersonal commandments. Regarding one who had vowed that another could not have any benefit from him, the mishnah states: ועוד אמר ר"מ: פותחין לו מן הכתוב In addition, R. Meir said, one “opens” (the way to retroactively שבתורה, ואומרין לו: אילו היית nullify a vow) for him with what is written in the Torah. -

Hemdat Yamim Korach

Korach Korach, 21 Sivan 5776 Post-Modernism in Ancient Times and Today Harav Yosef Carmel We will discuss those who Israelis call elitot (members of the “elite” class), who have been championing a spiritual trend in which the individual is at the center, and religious, ethnic, or national groups take a backseat. Personal rights overcome obligations to the public, and individuality is not just part of the mosaic of society but has the power of “for me the world was created.” For such people, irrefutable authority, whether political or spiritual, is foreign, which explains a lot of what we see. In the past few parshiyot , different people have challenged Moshe’s leadership. Eldad and Meidad prophesied in the encampment without Moshe’s permission. Yehoshua wanted to take action against them (Bamidbar 11:28), but Moshe refused: “If only the entire nation of Hashem could be prophets, that Hashem would place His spirit upon them” (ibid. 29). In our parasha , Korach openly opposed Moshe. He was an elitist, as Chazal said that he was a great scholar and one of the people who carried the Holy Ark (Bamidbar Rabba 18:3). The Torah also describes his 250 associates as part of the elite of society ( kri’ei moed, anshei shem – Bamidbar 16:2; see Sanhedrin 110a). They all complained that since the entire congregation is holy, there is no excuse for Moshe and Aharon to exert such control. “Everyone has the ability to lead himself”! In this case, Moshe’s reacted very differently, setting a showdown intended to doom the losers to death. -

Daf Ditty Pesachim 113: Kaldiyyim, Kalda'ei

Daf Ditty Pesachim 113: kaldiyyim, kalda'ei, The countries around Chaldea The fame of the Chaldeans was still solid at the time of Cicero (106–43 BC), who in one of his speeches mentions "Chaldean astrologers", and speaks of them more than once in his De divinatione. Other classical Latin writers who speak of them as distinguished for their knowledge of astronomy and astrology are Pliny, Valerius Maximus, Aulus Gellius, Cato, Lucretius, Juvenal. Horace in his Carpe diem ode speaks of the "Babylonian calculations" (Babylonii numeri), the horoscopes of astrologers consulted regarding the future. In the late antiquity, a variant of Aramaic language that was used in some books of the Bible was misnamed as Chaldean by Jerome of Stridon. That usage continued down the centuries, and it was still customary during the nineteenth century, until the misnomer was corrected by the scholars. 1 Rabbi Yoḥanan further said: The Holy One, blessed be He, proclaims about the goodness of three kinds of people every day, as exceptional and noteworthy individuals: About a bachelor who lives in a city and does not sin with women; about a poor person who returns a lost object to its owners despite his poverty; and about a wealthy person who tithes his produce in private, without publicizing his behavior. The Gemara reports: Rav Safra was a bachelor living in a city. 2 When the tanna taught this baraita before Rava and Rav Safra, Rav Safra’s face lit up with joy, as he was listed among those praised by God. Rava said to him: This does not refer to someone like the Master. -

Musical Instruments and Recorded Music As Part of Shabbat and Festival Worship

Musical Instruments and Recorded Music as Part of Shabbat and Festival Worship Rabbis Elie Kaplan Spitz and Elliot N. Dorff Voting Draft - 2010. She’alah: May we play musical instruments or use recorded music on Shabbat and hagim as part of synagogue worship? If yes, what are the limitations regarding the following: 1. Repairing a broken string or reed 2. Tuning string or wind instruments 3. Playing electrical instruments and using prerecorded music 4. Carrying the instrument 5. Blowing the shofar 6. Qualifications and pay of musicians I. Introduction The use of musical instruments as an accompaniment to services on Shabbat and sacred holidays (yom tov) is increasing among Conservative synagogues. During a recent United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism’s biennial conference, a Shabbat worship service included singing the traditional morning prayers with musician accompaniment on guitar and electronic keyboard.1 Previously, a United Synagogue magazine article profiled a synagogue as a model of success that used musical instruments to enliven its Shabbat services.2 The matter-of-fact presentation written by its spiritual leader did not suggest any tension between the use of musical instruments and halakhic norms. While as a movement we have approved the use of some instruments on Shabbat, such as the organ, we remain in need of guidelines to preserve the sanctity of the holy days. Until now, the CJLS (Committee of Jewish Law and Standards) has not analyzed halakhic questions that relate to string and wind instruments, such as 1 See “Synagogues Become Rock Venues: Congregations Using Music to Revitalize Membership Rolls,” by Rebecca Spence, Forward, January 4, 2008, A3. -

Jewish Law Research Guide

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Law Library Research Guides - Archived Library 2015 Jewish Law Research Guide Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides Part of the Religion Law Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Repository Citation Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library, "Jewish Law Research Guide" (2015). Law Library Research Guides - Archived. 43. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides/43 This Web Page is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Library Research Guides - Archived by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Home - Jewish Law Resource Guide - LibGuides at C|M|LAW Library http://s3.amazonaws.com/libapps/sites/1185/guides/190548/backups/gui... C|M|LAW Library / LibGuides / Jewish Law Resource Guide / Home Enter Search Words Search Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and ostensibly non-religious life. Home Primary Sources Secondary Sources Journals & Articles Citations Research Strategies Glossary E-Reserves Home What is Jewish Law? Need Help? Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Halakha from the Hebrew word Halakh, Contact a Law Librarian: which means "to walk" or "to go;" thus a literal translation does not yield "law," but rather [email protected] "the way to go". Phone (Voice):216-687-6877 Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and Text messages only: ostensibly non-religious life 216-539-3331 Jewish religious tradition does not distinguish clearly between religious, national, racial, or ethnic identities. -

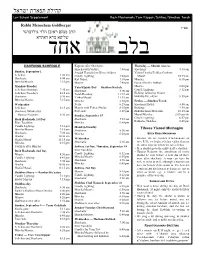

קהילת תפארת ישראל ����Lev Echad Supplement / ��� ������ ��-����Rosh Hashanah/Yom ���� Kippur/Sukkos/Simchasbwelcome to Torah

קהילת תפארת ישראל Lev Echad Supplement / -Rosh Hashanah/Yom Kippur/Sukkos/SimchasbWelcome to Torah CongregationRabbi Menachem Tiferes Goldberger Yisroel! Parshas Tazria/Metzora בס״ד Rabbi Goldberger Shiurim הרב מנחם ראובן הלוי גולדברגר Rabbi Goldberger has resumed his afternoon shiur for men and women. We will be studying the Haggada ,שליטא Mincha מרא hour beforeדאתרא On Shabbos, one shel Pesach with commentaries. Yankelove in Lakewood, NJ. בלב אחד DAVENING SCHEDULE Kaparos after Shacharis: Thursday — Shmini Atzeres Mincha with Viduyi: 4:00 pm Shacharis: 8:30 am Sunday, September 1 Seudah Hamafsekes/Bless children Yizkor/Drasha/Tefillas Geshem/ Selichos: 1:00 am Candle Lighting: 7:00 pm Musaf: 10:45 am Shacharis: 8:00 am Kol Nidrei: 7:10 pm Mincha: 6:10 pm Mincha/Maariv: 7:15 pm Maariv: 7:40 pm Farewell to the Sukkah Maariv: 8:00 pm Monday-Tuesday Yom Kippur Day — Shabbos Kodesh Candle Lighting: 8:12 pm Selichos (Monday): 7:45 am Shacharis: 8:00 am Bidding following Maariv Selichos (Tuesday): 6:10 am Torah Reading: 11:15 am Hakafos/five aliyos: 8:50 pm Shacharis: 6:30 am Yizkor/Musaf: 11:45 am Mincha/Maariv: 7:15 pm Mincha: 4:50 pm Friday — Simchas Torah Wednesday Neila: 6:25 pm Shacharis/Hallel: 8:00 am Selichos: 5:15 am Maariv with Tekias Shofar: 8:15 pm Bidding: 9:30 am Shacharis followed by Fast ends: 8:29 pm Hakafos/Krias HaTorah: 10:15 am Musaf/Mincha: 2:00 pm ish Hataras Nedarim: 6:30 am Sunday, September 15 Candle Lighting: 6:37 pm Rosh Hashanah, 1st Day Shacharis: 7:55 am Kabbalas Shabbos: 6:40 pm Eruv Tavshilin Mincha: 6:50 pm Candle Lighting: 7:14 pm Monday-Tuesday Tiferes Yisroel Minhagim Mincha/Maariv: 7:15 pm Shacharis: 6:30 am Shacharis: 7:30 am Mincha: 6:50 pm EREV ROSH HASHANAH Drasha: 10:30 am Because we are marbeh b’tachanunim on Shofar/Musaf: 11:15 am Wednesday • erev R”H, we begin selichos earlier than on Mincha: 6:15 pm Shacharis: 6:30 am the other days on which we say selichos. -

Derech Hateva 2018.Pub

Derech HaTeva A Journal of Torah and Science A Publication of Yeshiva University, Stern College for Women Volume 22 2017-2018 Co-Editors Elana Apfelbaum | Tehilla Berger | Hannah Piskun Cover & Layout Design Shmuel Ormianer Printing Advanced Copy Center, Brooklyn, NY 11230 Acknowledgements The editors of this year’s volume would like to thank Dr. Harvey Babich for the incessant time and effort that he devotes to this journal. Dr. Babich infuses his students with a passion for the Torah Umadda vision and serves as an exemplar of this philosophy to them. Through his constant encouragement and support, students feel confident to challenge themselves and find interesting connections between science and Torah. Dr. Babich, thank you for all the effort you contin- uously devote to us through this journal, as well as to our personal and future lives as professionals and members of the Jewish community. The publication of Volume 22 of this journal was made possible thanks to the generosity of the following donors: Dr. and Mrs. Harvey Babich Mr. and Mrs. Louis Goldberg Dr. Fred and Dr. Sheri (Rosenfeld) Grunseid Rabbi and Mrs. Baruch Solnica Rabbi Joel and Dr. Miriam Grossman Torah Activities Council YU Undergraduate Admissions We thank you for making this opportunity possible. Elana Apfelbaum Tehilla Berger Hannah Piskun Dedication We would like to dedicate the 22nd volume of Derech HaTeva: A Journal of Torah and Science to the soldiers of the Israel Defence Forces (IDF). Formed from the ashes of the Holocaust, the Israeli army represents the enduring strength and bravery of the Jewish people. The soldiers of the IDF have risked their lives to protect the Jewish nation from adversaries in every generation in wars such as the Six-Day War and the Yom Kippur War. -

Guide to Hebrew Transliteration and Rabbinic Texts

Guide to using Rabbinic texts: Transliteration issues: Hebrew has a different phonetic structure from English, and there is no universally accepted transliteration system. Therefore, the same title or word might show up in English works with diverse spellings. Here are a few things you can look for. Consonants ß The Hebrew letter b is usually an English B, but under some circumstances it is pronounced as a V. In those cases, it can be transliterated as either b, b, or v. (In German, it might even show up as a w.) ß Hebrew w can show up as either a v or a w. ß Hebrew x is an aspirated h sound, and is correctly transliterated as a h 9 (with a dot underneath). Ashkenazic Jews pronounce it as a gutteral, like the soft k (see below), and so it is often transliterated as a kh or ch. ß The Hebrew y, which is a Y consonant, might be transliterated as i or j (especially in German works). ß Similarly, the letter k is usually a simple K, but under some circumstances it is a guttural (Scottish/German) ch or kh sound, and is transliterated accordingly. ß Hebrew p can be either a P or F sound, depending on certain grammatical rules. In the latter case, it can be written as a p, p, f or ph. ß The Hebrew c is an emphatic S sound with no real equivalent in English. The correct transliteration is s,9 but Ashkenazic Jews generally pronounce it as a TZ sound, so that it will be transliterated as z, tz, ts, c or.ç. -

Download File

Halevy, Halivni and The Oral Formation of the Babylonian Talmud Ari Bergmann Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Ari Bergmann All rights reserved ABSTRACT Halevy, Halivni and The Oral Formation of the Babylonian Talmud Ari Bergmann This dissertation is dedicated to a detailed analysis and comparison of the theories on the process of the formation of the Babylonian Talmud by Yitzhak Isaac Halevy and David Weiss Halivni. These two scholars exhibited a similar mastery of the talmudic corpus and were able to combine the roles of historian and literary critic to provide a full construct of the formation of the Bavli with supporting internal evidence to support their claims. However, their historical construct and findings are diametrically opposed. Yitzhak Isaac Halevy presented a comprehensive theory of the process of the formation of the Talmud in his magnum opus Dorot Harishonim. The scope of his work was unprecedented and his construct on the formation of the Talmud encompassed the entire process of the formation of the Bavli, from the Amoraim in the 4th century to the end of the saboraic era (which he argued closed in the end of the 6th century). Halevy was the ultimate guardian of tradition and argued that the process of the formation of the Bavli took place entirely within the amoraic academy by a highly structured and coordinated process and was sealed by an international rabbinical assembly. While Halevy was primarily a historian, David Weiss Halivni is primarily a talmudist and commentator on the Talmud itself. -

SYNOPSIS the Mishnah and Tosefta Are Two Related Works of Legal

SYNOPSIS The Mishnah and Tosefta are two related works of legal discourse produced by Jewish sages in Late Roman Palestine. In these works, sages also appear as primary shapers of Jewish law. They are portrayed not only as individuals but also as “the SAGES,” a literary construct that is fleshed out in the context of numerous face-to-face legal disputes with individual sages. Although the historical accuracy of this portrait cannot be verified, it reveals the perceptions or wishes of the Mishnah’s and Tosefta’s redactors about the functioning of authority in the circles. An initial analysis of fourteen parallel Mishnah/Tosefta passages reveals that the authority of the Mishnah’s SAGES is unquestioned while the Tosefta’s SAGES are willing at times to engage in rational argumentation. In one passage, the Tosefta’s SAGES are shown to have ruled hastily and incorrectly on certain legal issues. A broader survey reveals that the Mishnah also contains a modest number of disputes in which the apparently sui generis authority of the SAGES is compromised by their participation in rational argumentation or by literary devices that reveal an occasional weakness of judgment. Since the SAGES are occasionally in error, they are not portrayed in entirely ideal terms. The Tosefta’s literary construct of the SAGES differs in one important respect from the Mishnah’s. In twenty-one passages, the Tosefta describes a later sage reviewing early disputes. Ten of these reviews involve the SAGES. In each of these, the later sage subjects the dispute to further analysis that accords the SAGES’ opinion no more a priori weight than the opinion of individual sages.