Musical Instruments and Recorded Music As Part of Shabbat and Festival Worship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

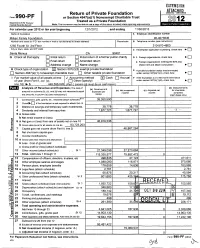

990-PF I Return of Private Foundation

EXTENSION Return of Private Foundation WNS 952 Form 990-PF I or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation 2012 Department of the Treasury Internal Reventie Service Note . The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting req For calendar year 2012 or tax year beginning 12/1/2012 , and ending 11/30/2013 Name of foundation A Employer identification number Milken Famil y Foundation 95-4073646 Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address ) Room /suite B Telephone number ( see instructions) 1250 Fourth St 3rd Floor 310-570-4800 City or town, state , and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending , check here ► Santa Monica CA 90401 G Check all that apply . J Initial return j initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations , check here ► Final return E Amended return 2 . Foreign organizations meeting the 85 % test, Address change Name change check here and attach computation ► H Check type of organization 0 Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947( a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust E] Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A). check here ► EJ I Fair market value of all assets at end J Accounting method Q Cash M Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination of year (from Part ll, col (c), Other (specify) under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here ---------------------------- ► llne 16) ► $ 448,596,028 Part 1 column d must be on cash basis Revenue The (d ) Disbursements Analysis of and Expenses ( total of (a) Revenue and (b ) Net investment (c) Adjusted net for chartable amounts in columns (b). -

The Impact of Camp Ramah on the Attitudes and Practices Of

122 Impact: Ramah in the Lives of Campers, Staff, and Alumni MITCHELL CoHEN The Impact of Camp Ramah on the Attitudes and Practices of Conservative Jewish College Students Adapted from the foreword to Research Findings on the Impact of Camp Ramah: A Companion Study to the 2004 “Eight Up” Report, a report for the National Ramah Commission, Inc. of The Jewish Theological Seminary, by Ariela Keysar and Barry A. Kosmin, 2004. The network of Ramah camps throughout North America (now serving over 6,500 campers and over 1,800 university-aged staff members) has been described as the “crown jewel” of the Conservative Movement, the most effec- tive setting for inspiring Jewish identity and commitment to Jewish communal life and Israel. Ismar Schorsch, chancellor emeritus of The Jewish Theological Seminary, wrote: “I am firmly convinced that in terms of social import, in terms of lives affected, Ramah is the most important venture ever undertaken by the Seminary” (“An Emerging Vision of Ramah,” in The Ramah Experience, 1989). Research studies written by Sheldon Dorph in 1976 (“A Model for Jewish Education in America”), Seymour Fox and William Novak in 1997 (“Vision at the Heart: Lessons from Camp Ramah on the Power of Ideas in Shaping Educational Institutions”), and Steven M. Cohen in 1998 (“Camp Ramah and Adult Jewish Identity: Long Term Influences”), and others all credit Ramah as having an incredibly powerful, positive impact on the devel- opment of Jewish identity. Recent Research on the Influence of Ramah on Campers and Staff I am pleased to summarize the findings of recent research on the impact of Ramah camping on the Jewish practices and attitudes of Conservative Jewish youth. -

Shabbat Shalom from Cyberspace May 11, 2013 - 2 Sivan 5773

Shabbat Shalom from Cyberspace May 11, 2013 - 2 Sivan 5773 SHABBAT SHALOM FROM CYBERSPACE BEMIDBAR/SHABUOT MAY 10-11, 2013 2 SIVAN 5773 Day 46 of the Omer Happy Mother’s Day to all and Happy Anniversary Chantelle SEPHARDIC CONGREGATION OF LONG BEACH We look forward to welcoming Baruch and Michal Abittan & Rabbi Dr. Meyer and Debra who along with Rebetzin Ida are sponsoring the Kidush in honor of their, daughter, granddaughter and great granddaughter Sarah Chaya, Abittan Friday Night: Candles: 7:41 PM - Afternoon and Evening service (Minha/Arbith): 7:00 PM Morning Service (Shaharith): 9:00AM –Please say Shemah at home by 8:29 AM 11:00 - 12:00 Orah's will be here with our Shabbat Morning Kids Program upstairs in the Rabbi's study. Stories, Tefillah, Games, Snacks and more . And Leah Colish will be babysitting down in the playroom 5:30 - Mincha Shabbat Afternoon Oneg with Rabbi Yosef and Leah; Treats, Stories, Basketball, Hula-hoop, Parsha Quiz, Tefillot, Raffles and Fun! Supervised play during Seudat Shelishit. 5:30: Ladies Torah Class at the Lemberger's 1 East Olive. Pirkei Avot 6:30 with Rabbi Aharon Minha: 7:00 PM – Seudah Shelishi and a Class 7:30 – with Rabbi David – Seudah Shelishi co-sponsored in honor of Chantelle and David’s anniversary and for all the moms on mother’s day … Evening Service (Arbith): 8:30 PM - Shabbat Ends: 8:41PM WEEKDAY TEFILLA SCHEDULE Shaharit Sunday8:00, Mon-Fri at 7:00 (6:55 Mondays and Thursdays) WEEKDAY TORAH CLASS SCHEDULE Daily 6:30 AM class – Honest Business Practices Monday Night Class with Rabba Yanai – 7PM Monday night LADIES: Wednesday Night 8PM with Esther Wein at various homes – continues next week Financial Peace University – Continues next Tuesday at 8PM The sisterhood will once again sponsor lunch the second day of shavuoth. -

Jewish Perspectives on Reproductive Realities by Rabbi Lori Koffman, NCJW Board Director and Chair of NCJW’S Reproductive Health, Rights and Justice Initiative

Jewish Perspectives on Reproductive Realities By Rabbi Lori Koffman, NCJW Board Director and Chair of NCJW’s Reproductive Health, Rights and Justice Initiative A note on the content below: We acknowledge that this document invokes heavily gendered language due to the prevailing historic male voices in Jewish rabbinic and biblical perspectives, and the fact that Hebrew (the language in which these laws originated) is a gendered language. We also recognize some of these perspectives might be in contradiction with one another and with some of NCJW’s approaches to the issues of reproductive health, rights, and justice. Background Family planning has been discussed in Judaism for several thousand years. From the earliest of the ‘sages’ until today, a range of opinions has existed — opinions which can be in tension with one another and are constantly evolving. Historically these discussions have assumed that sexual intimacy happens within the framework of heterosexual marriage. A few fundamental Jewish tenets underlie any discussion of Jewish views on reproductive realities. • Protecting an existing life is paramount, even when it means a Jew must violate the most sacred laws.1 • Judaism is decidedly ‘pro-natalist,’ and strongly encourages having children. The duty of procreation is based on one of the earliest and often repeated obligations of the Torah, ‘pru u’rvu’, 2 to be ‘fruitful and multiply.’ This fundamental obligation in the Jewish tradition is technically considered only to apply to males. Of course, Jewish attitudes toward procreation have not been shaped by Jewish law alone, but have been influenced by the historic communal trauma (such as the Holocaust) and the subsequent yearning of some Jews to rebuild community through Jewish population growth. -

Doing Talmud: an Ethnographic Study in a Religious High School in Israel

Doing Talmud: An Ethnographic Study in a Religious High School in Israel Thesis submitted for the degree of “Doctor of Philosophy” by Aliza Segal Submitted to the Senate of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem May 2011 Iyyar 5771 This work was carried out under the supervision of: Prof. Marc Hirshman Dr. Zvi Bekerman Acknowledgements If an apt metaphor for the completion of a dissertation is the birthing of a child, then indeed it takes a village to write a dissertation. I am fortunate that my village is populated with insightful, supportive and sometimes even heroic people, who have made the experience not only possible but also enriching and enjoyable. My debt of gratitude to these villagers looms large, and I would like to offer a few small words of thanks. To my advisors, Dr. Zvi Bekerman and Professor Menachem (Marc) Hirshman, for their generosity with time, insight, expertise, and caring. I have been working with Zvi since my MA thesis, and he has shaped my world view not only as a researcher but also as an individual. His astute and lightening-speed comments on everything I have ever sent him to read have pushed me forwards at every stage of my work, and it is with great joy that I note that I have never left his office without something new to read. Menachem has brought his keen eye and sharp wit to the project, and from the beginning has been able to see the end. His attention to the relationship between structure and content has informed my work as both a writer and a reader. -

Jewish Summer Camping and Civil Rights: How Summer Camps Launched a Transformation in American Jewish Culture

Jewish Summer Camping and Civil Rights: How Summer Camps Launched a Transformation in American Jewish Culture Riv-Ellen Prell Introduction In the first years of the nineteen fifties, American Jewish families, in unprecedented numbers, experienced the magnetic pull of suburbanization and synagogue membership.1 Synagogues were a force field particularly to attract children, who received not only a religious education to supplement public school, but also a peer culture grounded in youth groups and social activities. The denominations with which both urban and suburban synagogues affiliated sought to intensify that force field in order to attract those children and adolescents to particular visions of an American Judaism. Summer camps, especially Reform and Conservative ones, were a critical component of that field because educators and rabbis viewed them as an experiment in socializing children in an entirely Jewish environment that reflected their values and the denominations‟ approaches to Judaism. Scholars of American Jewish life have produced a small, but growing literature on Jewish summer camping that documents the history of some of these camps, their cultural and aesthetic styles, and the visions of their leaders.2 Less well documented is the socialization that their leaders envisioned. What happened at camp beyond Sabbath observance, crafts, boating, music, and peer culture? The content of the programs and classes that filled the weeks, and for some, the months at camp has not been systematically analyzed. My study of program books and counselor evaluations of two camping movements associated with the very denominations that flowered following 1 World War II has uncovered the summer camps‟ formulations of some of the interesting dilemmas of a post-war American Jewish culture. -

Guide to Practical Halacha and Home Ritual for Conservative Jews

DRAFT Guide to Practical Halacha and Home Ritual For Conservative Jews By Yehuda Wiesen Last Revised August 11, 2004 I am looking for a publisher for this Guide. Contact me with suggestions. (Contact info is on page 2.) Copyright © 1998,1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004 Joel P. Wiesen Newton, Massachusetts 02459 Limited and revocable permission is granted to reproduce this book as follows: (a) the copyright notice must remain in place on each page (if less than a page is reproduced, the source must be cited as it appears at the bottom of each page), (b) the reproduction may be distributed only for non-profit purposes, and (c) no charge may be made for copying, mailing or distribution of the copies. All requests for other reproduction rights should be addressed to the author. DRAFT Guide to Practical Halacha and Home Ritual For Conservative Jews Preface Many Conservative Jews have a strong desire to learn some practical and ritual halacha (Jewish law) but have no ready source of succinct information. Often the only readily available books or web sites present an Orthodox viewpoint. This Guide is meant to provide an introduction to selected practical halachic topics from the viewpoint of Conservative Judaism. In addition, it gives some instruction on how to conduct various home rituals, and gives basic guidance for some major life events and other situations when a Rabbi may not be immediately available. Halacha is a guide to living a religious, ethical and moral life of the type expected and required of a Jew. Halacha covers all aspects of life, including, for example, food, business law and ethics, marriage, raising children, birth, death, mourning, holidays, and prayer. -

What We LOVE About Being Jewish!

the Volume 31, Number 7 March 2012 TEMPLE BETH ABRAHAM Adar / Nisan 5772 What we LOVE about being Jewish! Volume 37•Number 7 March 2018•Adar 5778 R i Pu M WHAT’S HAPPENING SERVICES SCHEDULE Please join us for an evening of Monday & Thursday Morning Minyan JEWISH MEDITATION In the Chapel, 8:00 a.m. Thursday, March 22, 7:00 - 8:30 p.m. On Holidays, start time is 9:00 a.m. Temple Beth Abraham Chapel Friday Evening (Kabbalat Shabbat) In the Chapel, 6:15 p.m. We will chant, meditate, learn and share together in community. Open to everyone, Candle Lighting (Friday) absolutely no previous experience required. March 2 5:46 p.m. Meditation supports the practice of presence. March 9 5:53 p.m. It boosts your immune system, calms your nerves, March 16 6:59 p.m. and helps us stay connected with what is most important. March 23 7:06 p.m. Future dates: April 19, May 26 March 30 7:12 p.m. RSVP by email [email protected], if you know you are planning to attend. Walk-ins always Shabbat Morning welcome! In the Sanctuary, 9:30 a.m. $18 cash or check payable at the event. Torah Portions (Saturday) The evening will be facilitated by TBA member March 3 Ki Tisa Jueli Garfinkle who is certified and has been teaching Jewish meditation since 2004. Jueli’s March 10 Vayakhel-Pekudei classes are based on the Jewish mystical tradition March 17 Vayikra and calendar, and always include meaningful March 24 Tzav everyday practices to cultivate March 31 Pesach I presence, joy, and connection. -

Next Year in Jerusalem: Constructions of Israeli Nationalism in High Holiday Rituals

Pursuit - The Journal of Undergraduate Research at The University of Tennessee Volume 2 Issue 1 Spring 2011 Article 7 March 2011 Next Year in Jerusalem: Constructions of Israeli Nationalism in High Holiday Rituals Amelia Caron University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/pursuit Recommended Citation Caron, Amelia (2011) "Next Year in Jerusalem: Constructions of Israeli Nationalism in High Holiday Rituals," Pursuit - The Journal of Undergraduate Research at The University of Tennessee: Vol. 2 : Iss. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/pursuit/vol2/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Volunteer, Open Access, Library Journals (VOL Journals), published in partnership with The University of Tennessee (UT) University Libraries. This article has been accepted for inclusion in Pursuit - The Journal of Undergraduate Research at The University of Tennessee by an authorized editor. For more information, please visit https://trace.tennessee.edu/pursuit. Pursuit: The Journal of Undergraduate Research at the University of Tennessee Copyright © The University of Tennessee Next Year in Jerusalem: Constructions of Israeli Nationalism in High Holiday Rituals AMELIA CARON Advisor: Tricia Redeker Hepner College Scholars Program, University of Tennessee, Knoxville This article explores the intersection of nationalism and Jewish identity main- tenance with High Holiday celebrations carried out in the Diaspora. Using directed interviews and participant observation, I took part in the rituals of Rosh Hashanah (the Jewish New Year) and Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement) to uncover the way that American Jews and Israelis living in the Jewish Diaspora create and sustain a dialogue with their “traditional” homeland, Israel. -

Daf Ditty Pesachim 113: Kaldiyyim, Kalda'ei

Daf Ditty Pesachim 113: kaldiyyim, kalda'ei, The countries around Chaldea The fame of the Chaldeans was still solid at the time of Cicero (106–43 BC), who in one of his speeches mentions "Chaldean astrologers", and speaks of them more than once in his De divinatione. Other classical Latin writers who speak of them as distinguished for their knowledge of astronomy and astrology are Pliny, Valerius Maximus, Aulus Gellius, Cato, Lucretius, Juvenal. Horace in his Carpe diem ode speaks of the "Babylonian calculations" (Babylonii numeri), the horoscopes of astrologers consulted regarding the future. In the late antiquity, a variant of Aramaic language that was used in some books of the Bible was misnamed as Chaldean by Jerome of Stridon. That usage continued down the centuries, and it was still customary during the nineteenth century, until the misnomer was corrected by the scholars. 1 Rabbi Yoḥanan further said: The Holy One, blessed be He, proclaims about the goodness of three kinds of people every day, as exceptional and noteworthy individuals: About a bachelor who lives in a city and does not sin with women; about a poor person who returns a lost object to its owners despite his poverty; and about a wealthy person who tithes his produce in private, without publicizing his behavior. The Gemara reports: Rav Safra was a bachelor living in a city. 2 When the tanna taught this baraita before Rava and Rav Safra, Rav Safra’s face lit up with joy, as he was listed among those praised by God. Rava said to him: This does not refer to someone like the Master. -

Welcome Letter

Welcome Letter Dear Guests, Welcome to Passover 5779 at Camp Ramah in California! We’re so glad you’re here. This program book includes all of the information you need to ensure a relaxing and meaningful stay. If you are joining us for the first time, we hope this book answers many of your questions. While it’s difficult to capture the warm, engaging spirit of our community on paper, these pages will give you a sense of what’s in store. We thank the entire Camp Ramah in California community for building such an inspirational, creative and diverse program. This special annual retreat demonstrates the vision our founders and board members had of offering year- round Jewish experiential living and learning programs. Let us know if there is anything we can do to help you enjoy your stay. We hope you take full advantage of all Camp Ramah in California has to offer. If you need assistance, please visit our concierge desk in the Ostrow lounge or locate one of the Camp Ramah in California staff members. We look forward to celebrating a meaningful holiday together. Chag Sameach! Kara Rosenwald Teri Naftalin Program Coordinator Hospitality Coordinator Rabbi Joe Menashe Ariella Moss Peterseil Randy Michaels Executive Director Camp Director Chief Operations & Financial Officer Passover at Ramah Camp Ramah in California’s warm, relaxed Passover community draws multigenerational guests from across the country and internationally, and includes singles, couples, families, empty nesters, college students, and grandparents. We welcome new participants every year with open arms, and are also delighted to reunite with friends we see each year who have become extended family. -

Jewish Law Research Guide

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Law Library Research Guides - Archived Library 2015 Jewish Law Research Guide Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides Part of the Religion Law Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Repository Citation Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library, "Jewish Law Research Guide" (2015). Law Library Research Guides - Archived. 43. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides/43 This Web Page is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Library Research Guides - Archived by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Home - Jewish Law Resource Guide - LibGuides at C|M|LAW Library http://s3.amazonaws.com/libapps/sites/1185/guides/190548/backups/gui... C|M|LAW Library / LibGuides / Jewish Law Resource Guide / Home Enter Search Words Search Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and ostensibly non-religious life. Home Primary Sources Secondary Sources Journals & Articles Citations Research Strategies Glossary E-Reserves Home What is Jewish Law? Need Help? Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Halakha from the Hebrew word Halakh, Contact a Law Librarian: which means "to walk" or "to go;" thus a literal translation does not yield "law," but rather [email protected] "the way to go". Phone (Voice):216-687-6877 Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and Text messages only: ostensibly non-religious life 216-539-3331 Jewish religious tradition does not distinguish clearly between religious, national, racial, or ethnic identities.