New Evidence About Sir Geoffrey Luttrell's Raid on Sempringham Priory, 1312

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of the Welles Family in England

HISTORY OFHE T WELLES F AMILY IN E NGLAND; WITH T HEIR DERIVATION IN THIS COUNTRY FROM GOVERNOR THOMAS WELLES, OF CONNECTICUT. By A LBERT WELLES, PRESIDENT O P THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OP HERALDRY AND GENBALOGICAL REGISTRY OP NEW YORK. (ASSISTED B Y H. H. CLEMENTS, ESQ.) BJHttl)n a account of tljt Wu\\t% JFamtlg fn fHassssacIjusrtta, By H ENRY WINTHROP SARGENT, OP B OSTON. BOSTON: P RESS OF JOHN WILSON AND SON. 1874. II )2 < 7-'/ < INTRODUCTION. ^/^Sn i Chronology, so in Genealogy there are certain landmarks. Thus,n i France, to trace back to Charlemagne is the desideratum ; in England, to the Norman Con quest; and in the New England States, to the Puri tans, or first settlement of the country. The origin of but few nations or individuals can be precisely traced or ascertained. " The lapse of ages is inces santly thickening the veil which is spread over remote objects and events. The light becomes fainter as we proceed, the objects more obscure and uncertain, until Time at length spreads her sable mantle over them, and we behold them no more." Its i stated, among the librarians and officers of historical institutions in the Eastern States, that not two per cent of the inquirers succeed in establishing the connection between their ancestors here and the family abroad. Most of the emigrants 2 I NTROD UCTION. fled f rom religious persecution, and, instead of pro mulgating their derivation or history, rather sup pressed all knowledge of it, so that their descendants had no direct traditions. On this account it be comes almost necessary to give the descendants separately of each of the original emigrants to this country, with a general account of the family abroad, as far as it can be learned from history, without trusting too much to tradition, which however is often the only source of information on these matters. -

Family Tree Maker

Ancestors of Ulysses Simpson Grant Generation No. 1 1. President Ulysses Simpson Grant, born 27 Apr 1822 in Point Pleasant, Clermont Co., OH; died 23 Jul 1885 in Mount McGregor, Saratoga Co., NY. He was the son of 2. Jesse Root Grant and 3. Hannah Simpson. He married (1) Julia Boggs Dent 22 Aug 1848. She was born 26 Jan 1826 in White Haven Plantation, St. Louis Co. MO, and died 14 Dec 1902 in Washington, D. C.. She was the daughter of "Colonel" Frederick Fayette Dent and Ellen Bray Wrenshall. Generation No. 2 2. Jesse Root Grant, born 23 Jan 1794 in Greensburg, Westmoreland Co., PA; died 29 Jan 1873 in Covington, Campbell Co., KY. He was the son of 4. Noah Grant III and 5. Rachel Kelley. He married 3. Hannah Simpson 24 Jun 1821 in The Simpson family home. 3. Hannah Simpson, born 23 Nov 1798 in Horsham, Philadelphia Co., PA; died 11 May 1883 in Jersey City, Coventry Co., NJ. She was the daughter of 6. John Simpson, Jr. and 7. Rebecca Weir. Children of Jesse Grant and Hannah Simpson are: 1 i. President Ulysses Simpson Grant, born 27 Apr 1822 in Point Pleasant, Clermont Co., OH; died 23 Jul 1885 in Mount McGregor, Saratoga Co., NY; married Julia Boggs Dent 22 Aug 1848. ii. Samuel Simpson Grant iii. Orville Grant iv. Clara Grant v. Virginia "Nellie" Grant vi. Mary Frances Grant Generation No. 3 4. Noah Grant III, born 20 Jun 1748; died 14 Feb 1819 in Maysville, Mason Co., KY. He was the son of 8. -

King Robert the Bruce

King Robert the Bruce By A. F. Murison KING ROBERT THE BRUCE CHAPTER I THE ANCESTRY OF BRUCE When Sir William Wallace, the sole apparent hope of Scottish independence, died at the foot of the gallows in Smithfield, and was torn limb from limb, it seemed that at last 'the accursed nation' would quietly submit to the English yoke. The spectacle of the bleaching bones of the heroic Patriot would, it was anticipated, overawe such of his countrymen as might yet cherish perverse aspirations after national freedom. It was a delusive anticipation. In fifteen years of arduous diplomacy and warfare, with an astounding expenditure of blood and treasure, Edward I. had crushed the leaders and crippled the resources of Scotland, but he had inadequately estimated the spirit of the nation. Only six months, and Scotland was again in arms. It is of the irony of fate that the very man destined to bring Edward's calculations to naught had been his most zealous officer in his last campaign, and had, in all probability, been present at the trial—it may be at the execution—of Wallace, silently consenting to his death. That man of destiny was Sir Robert de Brus, Lord of Annandale and Earl of Carrick. The Bruces came over with the Conqueror. The theory of a Norse origin in a follower of Rollo the Ganger, who established himself in the diocese of Coutances in Manche, Normandy, though not improbable, is but vaguely supported. The name is territorial; and the better opinion is inclined to connect it with Brix, between Cherbourg and Valognes. -

For a Pdf of This Short Feature, Click Here

Scotland’s forgotten medieval king By Matthew Hammond If you pick up any popular history of Scotland’s kings and queens, chances are you will find no mention of Edward Balliol. Yet Edward was crowned king of Scots at Scone on 24 September, 1332, enthroned by the earl of Fife and anointed by the bishop of Dunkeld, with a bevy of worthies in attendance. Edward certainly had a reasonable claim to the kingship. His father, John Balliol, had been inaugurated at Scone in 1292 and reigned until 1296, when King Edward I invaded and stripped King John of his royal insignia, making him an ‘empty coat’ (‘Toom Tabard’ in Scots). Yet Balliol almost certainly had the superior claim to the Scots throne after the deaths of Alexander III (1286) and Margaret of Norway (1290), and Scottish patriots like William Wallace continued fighting in John’s name for years after his humiliating defeat. Image: Seal of King Edward Balliol - reverse Edward, John’s son, was already about 49 years old when he was crowned king of Scots, having spent a life of privilege and luxury, growing up in the courts of the future Edward II as well as his cousin John de Warenne, earl of Surrey. After his father’s death in 1314, Edward succeeded to the Balliol estates in France, centred on the château of Hélicourt in Vimeu in Picardy. Edward’s potential claim to the Scottish kingship became the focus for a group of nobles disinherited by Robert I. Some of these had been Scottish families who fled the kingdom, Balliol adherents and Bruce enemies like the MacDougalls of Lorn in Argyll, or the MacDowalls in Galloway. -

ISABEL DE BEAUMONT, DUCHESS of LANCASTER (C.1318-C.1359) by Brad Verity1

THE FIRST ENGLISH DUCHESS -307- THE FIRST ENGLISH DUCHESS: ISABEL DE BEAUMONT, DUCHESS OF LANCASTER (C.1318-C.1359) by Brad Verity1 ABSTRACT This article covers the life of Isabel de Beaumont, wife of Henry of Grosmont, Duke of Lancaster. Her parentage and chronology, and her limited impact on the 14th century English court, are explored, with emphasis on correcting the established account of her death. It will be shown that she did not survive, but rather predeceased, her husband. Foundations (2004) 1 (5): 307-323 © Copyright FMG Henry of Grosmont (c.1310-1361), Duke of Lancaster, remains one of the most renowned figures of 14th century England, dominating the military campaigns and diplomatic missions of the first thirty years of the reign of Edward III. By contrast, his wife, Isabel ― the first woman in England to hold the title of duchess ― hides in the background of the era, vague to the point of obscurity. As Duke Henry’s modern biographer, Kenneth Fowler (1969, p.215), notes, “in their thirty years of married life she hardly appears on record at all.” This is not so surprising when the position of English noblewomen as wives in the 14th century is considered – they were in all legal respects subordinate to their husbands, expected to manage the household, oversee the children, and be religious benefactresses. Duchess Isabel was, in that mould, very much a woman of her time, mentioned in appropriate official records (papal dispensation requests, grants that affected lands held in jointure, etc.) only when necessary. What is noteworthy, considering the vast estates of the Duchy of Lancaster and her prominent social position as wife of the third man in England (after the King and the Black Prince), is her lack of mention in contemporary chronicles. -

BIH All Chapters

"The glory of children are their Fathers." Proverbs XVII. 6. The Beaumonts in History A.D. a50 - m60 W Edward T. Beaumont, J.P., 1, Staverton Road, OXFORD. Author of Ancient Memorial Brasses, Academical Kabit illustrated by Memorial Brasses and Three Interesting Hampehire Brasses. Member of the OxEord Architectural and Historical Society. "Pur remernbrer des ancessoura Li fez B li diz B li mours .. , .. Li felonies des felons B li barnages des barons" (1) Le Roman de Rou L.I., Wace, 1100-1184. (1) To commemorate the deeds, the sayings, ,md manners of our ancestor3 and to tell of the evil acts oI" felons and the feats of arms of the barom. i. ~ONT~NT~. Rage Introductory ii Chapter I The Norsemen 1 W I1 The Norman Family - TheEarls of Leicester 9 111 W - The Earls of Warwick 36 W IV n - The Earls of Worcester 49 n V The Devonshire Beaumonts 56 W VI TheLincolnshire - The CarltonTowers Bzmily 73 VI1 The Laicestershire - The Cole Orton Family 118 VI11 N - The Grace Dieu 148 1) IX W - The Stoughton Qrange 174 W x n - The Barrow on Trent 190 W XI W - The BucklandCourt and Hackney 196 " XI1 W - The Wednesbury 201 XI11 n - The Elarrow on Soar W 204 " XIV The Suf.folkBeaumonts - The Hadleigh 206 W xv W n - The Coggeshall 248 " XVI n W - The Dunwich 263 XVII The Yorkshire Whitley- The 257 XVIII W W - The Bretton ana Hexham Abbey 'I 297 " XIX l1 W - The Bridgford Hill 310 n M[ n W - The Lascells Hall and Mirfield 315 XXI W W - The Caltor, Family It 322 Conolusion 324 THE BIGAUMDNTS IN HISTORY INTRODUCTORY. -

"?3<AC7D 43CA@7D" <@ E:7 D75A@6 :3>8 A8 E:7 C7<9@ A8

D96 !>2;@B6C 32B@?6C! ;? D96 C64@?5 92=7 @7 D96 B6;8? @7 65F2B5 ;$ ")*/(%)+(.# 56B6< 2& 32BB;6 2 DNKWOW CYHROXXKJ LTV XNK 5KMVKK TL AN5 GX XNK ESOZKVWOX] TL CX 2SJVK[W )//) 7YQQ RKXGJGXG LTV XNOW OXKR OW GZGOQGHQK OS BKWKGVIN1CX2SJVK[W07YQQDK\X GX0 NXXU0''VKWKGVIN%VKUTWOXTV]&WX%GSJVK[W&GI&YP' AQKGWK YWK XNOW OJKSXOLOKV XT IOXK TV QOSP XT XNOW OXKR0 NXXU0''NJQ&NGSJQK&SKX')((*+',-/, DNOW OXKR OW UVTXKIXKJ H] TVOMOSGQ ITU]VOMNX DNOW OXKR OW QOIKSWKJ YSJKV G 4VKGXOZK 4TRRTSW =OIKSWK THE ~IORBS BAROBBS IN THE SECOND HALF OF rHE REIGN OF EDWARD I (1290-1307) Derek A. Barrie Submitted for the degree of Ph.D., University of St.Andrews 30 September 1991 ABSTRACT The second half of the reign of Edward I saw the emergence;of a parliamentary peerage in embryo. The maiores barones comprising it owed their position to regular individual summonses to parliament and to major military campaigns of the period, particularly in Scotland. This was ~I coupled with either substantial wealth based on landholdings, though not a particular type of tenure, or a lengthy record of loyal service to the Crown either in one particular area of local or national government or over a range of activities. Service to the Crown, outwith provision of advice and counsel in parliament and cavalry service in major campaigns, was not as widespread as many historians have argued. Such service was primarily, though not exclusively, local, performed in counties where maiores barones had their principal estates. It covered military activity outwith major campaigns; keeperships of castles; preparations for war; the administration of justice; dependency government; diplomatic service overseas and the royal household. -

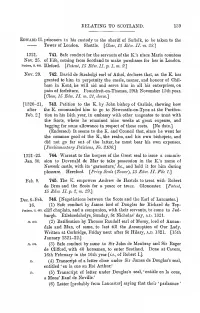

1321 to 1330

' EELATING TO SCOTLAND. 139 Edward II. prisoners ia liis custody to the sheriff of Suffolk, to be taken to the Tower of London. Shottle. [Close, 15 Echo. II. m. S8.] 132L 741. Safe conduct for the servants of the K.'s niece Maria countess Nov. 25. of Fife, coining from Scotland to make purchases for her in London. Foedera, li. 460. lUeford. [Patent, 15 Edw. 11. p. 1, m. 9] Nov. 29. 742. David de Strabolgi earl of Athol, declares that, as the K. has granted to him in perpetuity the castle, manor, and honour of Chil- ham in Kent, he will aid and serve him in all his enterprises, on pain of forfeiture. Pountfreit-on-Thames, 29th November 15th year. [Close, 15 Edw. II. m. SI, dorse.'] [1320-21, 743. Petition to the K. by John bishop of Carlisle, shewing how after the K. commanded him to go to Newcastle-on-Tyne at the Purifica- Feb. 2.] tion in his 14th year, in embassy with other magnates to treat with the Scots, where he remained nine weeks at great expense, and begging for some allowance in respect of these costs. [No date.] (Endorsed) It seems to the K. and Council that, since he went for the common good of the K., the realm, and his own bishopric, and did not go far out of the latter, he must bear his own expenses. [Parlia')ne7itary Petitions, No. SIOO.] 1321-22. 744 Warrant to the keepers of the Great seal to issue a commis- Jan. 30. sion to Dovenald de Mar to take possession in tlie K.'s name of Newerk castle, with its ' garnesture,' &c., and hold it for him during pleasure. -

BIH Chapter 06

73. CHAPTER VI. THE LINCOLNSHIRX CEAUMONTS - TJTJ CP-RLTON TOWERS FA'diLY. "Our acts, our angsls are, or good or ill, Our fatal shadovs (disguisesj that walk by us still." Beaumont and Fletcher, UPON AN HONEST MAN' S FORTUNE, 11. 499, Darleg Ed. Arms, Quarterly first and fourth, arg. a lion, rampant, sa. for Stapleton second and third, argr two bars, and in chief, three escallo9s az for Errington, Motto: "Mieux sera". (Better times are coming). Genealogical chart shewing Lhe connection of %he family on the female side with theRoyal houses of England and Portugal. Raymond Berenger,Count of Provence, married Seatrix daughter I of Thomas, Count of Savoy. -----------___-____-__________________________L I I I I Margare t Eleanor mar- SouchLer Beatrice married ried Henry married marr i ed S. Louis IX I11 King of Richa1.d Charles I King of England Earl of Earl of Franc e I Cornwall Anjou l King of King of I the Jerusalem, Naples and I Romans Sicily; son of Louis 1 VI11 of France I ---I I I l I Edward I 3:dmund Crouch- Charles I1 Louis of I back, 1st. Earl King of' Bri enne Edwara I1 of Lancaster Jerusalem married I ----_---.---_ Agnes Edward I1 I I l Vicomtesse I Thomas 2nd Henry Plan- de I Earl of tagenet Srd Beaumont I Lancaster Earl of l I Lancaster I I l I I I 1 (Edward 111) (Henry Plantagenet (Vicomtesse de Beaumont) I Earl 3rd of Lan- I l aaater) I I -- l I I I I I I Richard I1 John of I Theobald LGuis Henry 1st Gaunt I Vicomte de Bishop Baron married I Bellomonte of I Blanche 1 ArchbishopDurham I grand- I of Paris I daughter Henry lat I of Sir Duke of I I Henry de Lancaster, John Isabei mar- Beaumontmarried 2nd Baron ried Henry I Isabel married 1st Duke of I daughterEleanor Lancaster I of Sir great- I I Henry de grancl- 1 Beaumont daughter I 1st Baron of Henry Blanche I I 111 (see married John I I C.T. -

Walker, Sharon Irene

Tyranny, Complaint and Redress: The Evidence of the Petitions Presented to the Crown C. 1320 to 1335 Sharon Irene Walker, BA BSc. MA Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2013 For my Father, Stanley Wood, 1927-1984. Love you Dad. Abstract This thesis offers a new approach to the understanding of the recurrent crises of the period c.1320 to 1335, covering the final years of Edward II’s turbulent reign, the deposition, and its repercussions into the period of the Regency and the first years of the majority rule of Edward III. This has been achieved through an archive led study of the accounts of the ‘complaint and redress’ encompassed in the records of the Ancient Petitions presented to the Crown, held by The National Archives and designated as the SC 8 series. These records contain some of the most vivid contemporary and individual records of the lives and concerns of the king’s subjects during this turbulent period. This thesis illustrates that these records contain the genuine ‘voice’ of the petitioners, and can be used to reveal the impact on those seeking the king’s justice during the recurring crises of this defining moment in late medieval English history. Although there has been much interest in the events leading to the deposition and death of Edward II, research to date has focused mainly on its effect on the noble members of society, their place in administrative and governmental history, and the workings of the judicial system. In contrast, this study considers the nature of these complaints and requests in order to illustrate specific events. -

Revised-Office of the Dead in English Books of Hours

?41 ;225/1 ;2 ?41 01-0 59 1937-90+ 58-31 -90 8@>5/ 59 ?41 .;;6 ;2 4;@=> -90 =17-?10 ?1A?>! /# &')%"/# &)%% >BQBI >DIFLL - ?IFRJR >TCMJSSFE GOQ SIF 0FHQFF OG <I0 BS SIF @NJUFQRJSX OG >S# -NEQFVR '%&& 2TLL MFSBEBSB GOQ SIJR JSFM JR BUBJLBCLF JN =FRFBQDI,>S-NEQFVR+2TLL?FWS BS+ ISSP+$$QFRFBQDI"QFPORJSOQX#RS"BNEQFVR#BD#TK$ <LFBRF TRF SIJR JEFNSJGJFQ SO DJSF OQ LJNK SO SIJR JSFM+ ISSP+$$IEL#IBNELF#NFS$&%%'($'&%* ?IJR JSFM JR PQOSFDSFE CX OQJHJNBL DOPXQJHIS THE OFFICE OF THE DEAD IN ENGLAND: IMAGE AND MUSIC IN THE BOOK OF HOURS AND RELATED TEXTS, C. 1250- C. 1500 SARAH SCHELL SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SCHOOL OF ART HISTORY, UNIVERSITY OF ST ANDREWS DECEMBER, 2009 1 ABSTRACT This study examines the illustrations that appear at the Office of the Dead in English Books of Hours, and seeks to understand how text and image work together in this thriving culture of commemoration to say something about how the English understood and thought about death in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The Office of the Dead would have been one of the most familiar liturgical rituals in the medieval period, and was recited almost without ceasing at family funerals, gild commemorations, yearly minds, and chantry chapel services. The Placebo and Dirige were texts that many people knew through this constant exposure, and would have been more widely known than other 'death' texts such as the Ars Moriendi. The images that are found in these books reflect wider trends in the piety and devotional practice of the time. -

Chief Justices of the Courts of Commmon Pleas and King's Bench

THE CHIEF JUSTICES OF THE COURTS OF COMMON PLEAS AND KING'S BENCH, 1327-1377 by URSULA MANN CASEY B. A., Scripps College, 1962 A MASTER'S THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of History KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 1979 Approved by: slajor PrcTess6r Jp-ce Call. LD .T<t C37 C. 1 Contents Page Chapter 1: Introduction 1 Chapter 2: The Courts and the Lawyers 7 Chapter 3: The Chief Justices of the Court of 17 Common Pleas Chapter 4: The Chief Justices of the Court of 43 King's Bench Chapter 5: Conclusion 87 Notes 104 Bibliography 146 Chapter 1 Introduction Since the publication of Edward Foss ' s The Judges of England in the mid-nineteenth century many pages of legal his- tory have been written, but very few have dealt with the personnel of the common law courts of England in any but a general way. While Foss's work is admirably ambitious in both scope and intention, and has been invaluable to scholars for more than a century, it would seem that the time for further inves- tigation of the histories and careers of these men is overdue. Much material which was unavailable to Foss might now add to, or even alter, the information he provides; and while it seems unlikely that anyone will again attempt a study of all the English judges, we can add substantially to Foss's information through works on individuals or smaller groups —patch-work, as Sayles terms it. In this paper I shall be concerned with the seventeen chief justices of the courts of king's bench and common pleas during the reign of Edward III, 1327-1377.