Impostures: Subjectivity, Memory, and Untruth in the Contemporary Memoir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feminine Style in the Pursuit of Political Power

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Talk “Like a Man”: Feminine Style in the Pursuit of Political Power DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Political Science by Jennifer J. Jones Dissertation Committee: Professor Kristen Monroe, Chair Professor Marty Wattenberg Professor Michael Tesler 2017 Chapter 4 c 2016 American Political Science Association and Cambridge University Press. Reprinted with permission. All other materials c 2017 Jennifer J. Jones TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES iv LIST OF TABLES vi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vii CURRICULUM VITAE viii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION xi 1 Introduction 1 2 Theoretical Framework and Literature Review 5 2.1 Social Identity and Its Effect on Social Cognition . 6 2.1.1 Stereotypes and Expectations . 9 2.1.2 Conceptualizing Gender in US Politics . 13 2.2 Gender and Self-Presentation in US Politics . 16 2.2.1 Masculine Norms of Interaction in Institutional Settings . 16 2.2.2 Political Stereotypes and Leadership Prototypes . 18 2.3 The Impact of Political Communication in Electoral Politics . 22 2.4 Do Women Have to Talk Like Men to Be Considered Viable Leaders? . 27 3 Methods: Words are Data 29 3.1 Approaches to Studying Language . 30 3.2 Analyzing Linguistic Style . 34 3.2.1 Gendered Communication and the Feminine/Masculine Ratio . 37 3.2.2 Comparison with Other Coding Schemes . 39 3.3 Approaches to Studying Social Perception and Attitudes . 40 3.3.1 The Link Between Linguistic Style and Implicit Associations . 42 4 The Linguistic Styles of Hillary Clinton, 1992–2013 45 4.1 The Case of Hillary Clinton . -

Mels Resume:Update2020

Melissa Street Makeup Artist Film/Television/Theater/Live Events cell: (858) 344-7201 email: [email protected] FILM: 2020 MAKEUP DEPARTMENT HEAD - GIGI - Director: Drew Sackheim. 2018 MAKEUP ARTIST - TOP GUN MAVERICK - PARAMOUNT - Director: Joseph Kosinski - Starring: Tom Cruise, Jennifer Connelly, Jon Hamm, Val Kilmer, Miles Teller. 2016 MAKEUP DEPARTMENT HEAD - THE RIDE - 100 ACRE FILMS - SHORT FILM - Director: Eric Addison 2014 MAKEUP DEPARTMENT HEAD - WALTER - ZERO GRAVITY Director: Anna Mastro - Starring: Andrew J. West, Virginia Madsen, William H. Macy, Leven Rambin, Peter Facinelli, Neve Campbell, Brian White, Jim Gaffigan, Justin Kirk, Milo Ventimiglia. Personal artist to: Virginia Madsen, William H. Macy, Andrew J. West, Peter Facinelli, Neve Campbell, Brian White. 2013 MAKEUP DEPARTMENT HEAD - SUPER ATHLETE - WHITE NIGHT PRODUC- TIONS Director: John Comrie - Starring: Tony Sirico, Christopher Lloyd, Faran Tahir, Cameron Rodriguez, Larry Van- Buren Jr. Personal artist to: Tony Sirico, Christopher Lloyd, Faran Tahir. 2011 KEY MAKEUP ARTIST - WHEN YOU FIND ME - SHORT FILM - PROJECT IMAG- IN8TION/FREESTYLE Director: Bryce Dallas-Howard - Starring: Marianna Palka, Erin Way, Jacy King, Karley Scott Collins, Devon Woods, Zachary James Rukavina. 2010 MAKEUP DEPARTMENT HEAD - THE HEIRESS LETHAL - SHORT FILM - EYE- FULL STUDIOS Director: Michael Brueggemeyer - Starring: Merrick McCartha, Cristyn Chandler, Ron Christopher Jones, Theresa Layne. 2003 MAKEUP DEPARTMENT HEAD - CARROT TOP ROCKS LAS VEGAS - DELTA EN- TERTAINMENT Director: Steve Hanft - Starring: Scott “Carrot Top” Thompson, Penn Jillette, Teller. 1986 UNCREDITED MAKEUP ASSISTANT - INVADERS FROM MARS - CANNON PIC- TURES Director: Tobe Hooper - Starring: Karen Black, Hunter Carson, Timothy Bottoms, James Karen, Laraine Newman. Makeup Assistant to Stan Winston F/X lab team. -

Journalists Denying Liberal Bias, Part Three

Journalists Denying Liberal Bias, Part Three More examples of journalists denying their liberal bias: "I'm not going to judge anybody else in the business, but our work — I can speak for NBC News and our newsroom — it goes through, talk about checks and balances. We have an inordinate number of editors. Every word I write, before it goes on air, goes through all kinds of traps and filters, and it's read by all kinds of different people who point out bias." — CNBC anchor Brian Williams on Comedy Central's The Daily Show, July 29, 2003. "Our greatest accomplishment as a profession is the development since World War II of a news reporting craft that is truly non-partisan, and non-ideological....It is that legacy we must protect with our diligent stewardship. To do so means we must be aware of the energetic effort that is now underway to convince our readers that we are ideologues. It is an exercise of, in disinformation, of alarming proportions, this attempt to convince the audience of the world's most ideology-free newspapers that they're being subjected to agenda-driven news reflecting a liberal bias. I don't believe our viewers and readers will be, in the long-run, misled by those who advocate biased journalism." — New York Times Executive Editor Howell Raines accepting the 'George Beveridge Editor of the Year Award,' February 20, 2003. CBS's Lesley Stahl: "Today you have broadcast journalists who are avowedly conservative.... The voices that are being heard in broadcast media today, are far more likely to be on the right and avowedly so, and therefore, more — almost stridently so, than what you're talking about." Host Cal Thomas: "Can you name a conservative journalist at CBS News?" Stahl: "I don't know of anybody's political bias at CBS News....We try very hard to get any opinion that we have out of our stories, and most of our stories are balanced." — Exchange on the Fox News Channel's After Hours with Cal Thomas, January 18, 2003. -

A Million Little Maybes: the James Frey Scandal and Statements on a Book Cover Or Jacket As Commercial Speech

Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 17 Volume XVII Number 1 Volume XVII Book 1 Article 5 2006 A Million Little Maybes: The James Frey Scandal and Statements on a Book Cover or Jacket as Commercial Speech Samantha J. Katze Fordham University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Samantha J. Katze, A Million Little Maybes: The James Frey Scandal and Statements on a Book Cover or Jacket as Commercial Speech, 17 Fordham Intell. Prop. Media & Ent. L.J. 207 (2006). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol17/iss1/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Million Little Maybes: The James Frey Scandal and Statements on a Book Cover or Jacket as Commercial Speech Cover Page Footnote The author would like to thank Professor Susan Block-Liebe for helping the author formulate this Note and the IPLJ staff for its assistance in the editing process. This note is available in Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol17/iss1/5 KATZE_FORMATTED_102606.DOC 11/1/2006 12:06 PM A Million Little Maybes: The James Frey Scandal and Statements on a Book Cover or Jacket as Commercial Speech Samantha J. -

Image and Narrative - Article

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Resisting the author: JT LeRoy's fictional authorship Loontjens, J. Publication date 2008 Document Version Final published version Published in Image & Narrative Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Loontjens, J. (2008). Resisting the author: JT LeRoy's fictional authorship. Image & Narrative, 9(22). http://www.imageandnarrative.be/inarchive/autofiction2/loontjes.html General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:29 Sep 2021 Image and Narrative - Article Online Magazine of the Visual Narrative - ISSN 1780-678X Home Editorial Board Policy Issue 22. Autofiction and/in Image - Autofiction visuelle II Resisting the Author: JT Leroy's fictional authorship Author: Jannah Loontjens Published: May 2008 Abstract (E): In the last decade, the interest in the relation between author and text, author and autobiography, seems to have grown. -

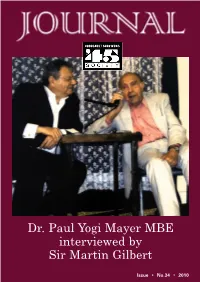

Dr. Paul Yogi Mayer MBE Interviewed by Sir Martin Gilbert

JOURNAL 2010:JOURNAL 2010 24/2/10 12:04 Page 1 Dr. Paul Yogi Mayer MBE interviewed by Sir Martin Gilbert Issue • No.34 • 2010 JOURNAL 2010:JOURNAL 2010 24/2/10 12:04 Page 2 CH ARTER ED AC C OU NTANTS MARTIN HELLER 5 North End Road • London NW11 7RJ Tel 020 8455 6789 • Fax 020 8455 2277 email: [email protected] REGISTERED AUDIT ORS simmons stein & co. SOLI CI TORS Compass House, Pynnacles Close, Stanmore, Middlesex HA7 4AF Telephone 020 8954 8080 Facsimile 020 8954 8900 dx 48904 stanmore web site www.simmons-stein.co.uk Gary Simmons and Jeffrey Stein wish the ’45 Aid every success 2 JOURNAL 2010:JOURNAL 2010 24/2/10 12:04 Page 3 THE ’45 AID SOCIETY (HOLOCAUST SURVIVORS) PRESIDENT SECRETARY SIR MARTIN GILBERT C.B.E.,D.LITT., F.R.S.L M ZWIREK 55 HATLEY AVENUE, BARKINGSIDE, VICE PRESIDENTS IFORD IG6 1EG BEN HELFGOTT M.B.E., D.UNIV. (SOUTHAMPTON) COMMITTEE MEMBERS LORD GREVILLE JANNER OF M BANDEL (WELFARE OFFICER), BRAUNSTONE Q.C. S FREIMAN, M FRIEDMAN, PAUL YOGI MAYER M.B.E. V GREENBERG, S IRVING, ALAN MONTEFIORE, FELLOW OF BALLIOL J KAGAN, B OBUCHOWSKI, COLLEGE, OXFORD H OLMER, I RUDZINSKI, H SPIRO, DAME SIMONE PRENDEGAST D.B.E., J.P., D.L. J GOLDBERGER, D PETERSON, KRULIK WILDER HARRY SPIRO SECRETARY (LONDON) MRS RUBY FRIEDMAN CHAIRMAN BEN HELFGOTT M.B.E., D.UNIV. SECRETARY (MANCHESTER) (SOUTHAMPTON) MRS H ELLIOT VICE CHAIRMAN ZIGI SHIPPER JOURNAL OF THE TREASURER K WILDER ‘45 AID SOCIETY FLAT 10 WATLING MANSIONS, EDITOR WATLING STREET, RADLETT, BEN HELFGOTT HERTS WD7 7NA All submissions for publication in the next issue (including letters to the Editor and Members’ News Items) should be sent to: RUBY FRIEDMAN, 4 BROADLANDS, HILLSIDE ROAD, RADLETT, HERTS WD7 7BX ACK NOW LE DG MEN TS SALEK BENEDICT for the cover design. -

The Apology | the B-Side | Night School | Madonna: Rebel Heart Tour | Betting on Zero Scene & Heard

November-December 2017 VOL. 32 THE VIDEO REVIEW MAGAZINE FOR LIBRARIES N O . 6 IN THIS ISSUE One Week and a Day | Poverty, Inc. | The Apology | The B-Side | Night School | Madonna: Rebel Heart Tour | Betting on Zero scene & heard BAKER & TAYLOR’S SPECIALIZED A/V TEAM OFFERS ALL THE PRODUCTS, SERVICES AND EXPERTISE TO FULFILL YOUR LIBRARY PATRONS’ NEEDS. Learn more about Baker & Taylor’s Scene & Heard team: ELITE Helpful personnel focused exclusively on A/V products and customized services to meet continued patron demand PROFICIENT Qualified entertainment content buyers ensure frontlist and backlist titles are available and delivered on time SKILLED Supportive Sales Representatives with an average of 15 years industry experience DEVOTED Nationwide team of A/V processing staff ready to prepare your movie and music products to your shelf-ready specifications Experience KNOWLEDGEABLE Baker & Taylor is the Full-time staff of A/V catalogers, most experienced in the backed by their MLS degree and more than 43 years of media cataloging business; selling A/V expertise products to libraries since 1986. 800-775-2600 x2050 [email protected] www.baker-taylor.com Spotlight Review One Week and a Day and target houses that are likely to be empty while mourners are out. Eyal also goes to the HHH1/2 hospice where Ronnie died (and retrieves his Oscilloscope, 98 min., in Hebrew w/English son’s medical marijuana, prompting a later subtitles, not rated, DVD: scene in which he struggles to roll a joint for Publisher/Editor: Randy Pitman $34.99, Blu-ray: $39.99 the first time in his life), gets into a conflict Associate Editor: Jazza Williams-Wood Wr i t e r- d i r e c t o r with a taxi driver, and tries (unsuccessfully) to hide in the bushes when his neighbors show Editorial Assistant: Christopher Pitman Asaph Polonsky’s One Week and a Day is a up with a salad. -

King of the Paranormal

King of the Paranormal CNN's Larry King Live has a long history of outrageous promotion of UFOs, psychics, and spiritualists. CHRIS MOONEY roadcast on CNN, the July 1, 2003, installment of Larry King Live was a sight to behold. The program, Bin Kings words, explored "the incredible events of fifty-six years ago at Roswell, New Mexico." What most likely crashed at Roswell in 1947 was a government spy bal- loon, but the panel of guests assembled on King's show pre- ferred a more sensational version of events. Jesse Marcel, Jr., son of a Roswell intelligence officer, claimed that just after the crash, his father showed him bits of debris that "came from another civilization" (Marcel 2003). Glenn Dennis, who worked at a Roswell funeral home at the time, said a military officer called him to ask about the availability of small caskets (i.e., for dead aliens). Later Dennis, obviously SKEPTICAL INQUIRER November/December 2003 a UFO enthusiast, abruptly observed that the pyramids in Roswell crash site. Doleman admitted to King rJiat his dig had Egypt had recently been "[shut down] for three or four days not yet yielded any definitive evidence, but added that the and no tourists going out there on account of the sightings" "results" of his analysis will air on Sci-Fi in October—as (Dennis 2003). opposed to, say, being published in a peer-reviewed scientific King's program didn't merely advance the notion that an journal (Doleman 2003). [See also David E. Thomas, "Bait alien spacecraft crashed at Roswell in 1947. -

Avatar: JT Leroy and Laura Albert'

THE A EPH REVIEW Avatar: JT Leroy Afshan Shaf and Laura Albert’ Laura Albert won international acclaim writing fction as JT LeRoy. She wrote works credited to Leroy, whom Albert described as an “avatar”, saying she was able to write things as Leroy that she could not have said as Laura Albert. She has also used the names Emily Frasier and Speedie. She was sued for fraud when she signed a flm option contract with her pseudonym; a jury found against her. Her dissimulation has been called one of greatest hoaxes in literary history. She is the author of the novels Sarah and Te Heart Is Deceitful Above All Tings, reissued by HarperCollins, and the novella Harold’s End. She is also the subject of Jef Feuerzeig’s feature documentary Author: Te JT LeRoy Story and Lynn Hershman Leeson’s flm Te Ballad of JT LeRoy. Cinema Eye, the organization that recognizes outstanding craft and artistry in nonfction flmmaking, cited Laura Albert in Author as one of its 2016 list of Unforgettables: the year’s most notable and signifcant nonfction-flm subjects. Laura contributes to print and online publications internationally, in a career that includes the cover feature for Man About Town and articles for Te New York Times, Te Forward, Te London Times, Spin, Film Comment, Filmmaker, Interview, I-D, Vogue, Te Face, Dazed and Confused, and VESTOJ, the Platform for Critical Tinking on Fashion. She was a contributing editor to Black Book, I-D, SOMA, and 7×7 magazines and is currently an editor for Diane Pernet’s A Shaded View On Fashion and the Outpost section of psychoPEDIA.com. -

The Holocaust As Public History

The University of California at San Diego HIEU 145 Course Number 646637 The Holocaust as Public History Winter, 2009 Professor Deborah Hertz HSS 6024 858 534 5501 Class meets 12---12:50 in Center 113 Please do not send me email messages. Best time to talk is right after class. It is fine to call my office during office hours. You may send a message to me on the Mail section of our WebCT. You may also get messages to me via Ms Dorothy Wagoner, Judaic Studies Program, 858 534 4551; [email protected]. Office Hours: Wednesdays 2-3 and Mondays 11-12 Holocaust Living History Workshop Project Manager: Ms Theresa Kuruc, Office in the Library: Library Resources Office, last cubicle on the right [turn right when you enter the Library] Phone: 534 7661 Email: [email protected] Office hours in her Library office: Tuesdays and Thursdays 11-12 and by appointment Ms Kuruc will hold a weekly two hour open house in the Library Electronic Classroom, just inside the entrance to the library to the left, on Wednesday evenings from 5-7. Students who plan to use the Visual History Archive for their projects should plan to work with her there if possible. If you are working with survivors or high school students, that is the time and place to work with them. Reader: Mr Matthew Valji, [email protected] WebCT The address on the web is: http://webct.ucsd.edu. Your UCSD e-mail address and password will help you gain entry. Call the Academic Computing Office at 4-4061 or 4-2113 if you experience problems. -

A Novel About Another Man for Whom a Moral Competition Which Becomes More and Running Is of Existential Importance

SCB DISTRIBUTORS IS Atides Publishing PROUD TO INTRODUCE Freedom Press Friends Without Borders Green Island Publishing Krell Press Mixofpix PottyMD Quarry Press R.I.C. Publications The Fell Press Wet Angel Books Cover design by Rama Crouch-Wong Layout by Dan Nolte Who Killed Hunter Thompson? An Inquiry Into the Life & Death of the Master of Gonzo Edited by Warren Hinckle “I think Thompson has remained a writer of significance because essentially a satirist, he has displayed utter contempt for power; political power, financial power, even show biz juice.” – Paul Theroux A look at the life of Hunter S. Thompson through essays and personal recollections from the Gonzo journalist’s peers, closest friends and co-conspirators—including transcripts of his rants and idiosyncratic phone messages. Thompson’s compatriots, who observe and comment on the journalistic legend’s life and death, include, among many others: I Susie Bright, the editor of On Our Backs and Best American Erotica I Jerry Brown, the former Governor of California and THE UNDERGROUND EULOGIES current Mayor of Oakland I Rick MacArthur, the publisher of Harper’s I Ben Fong-Torres, the iconic Rolling Stone editor I Eugene “Dr. Hip” Schoenfeld, the pot guru I Ralph Steadman, the illustrator for Thompson’s covers, Who Killed as well as for Pink Floyd’s The Wall Hunter Thompson? An Inquiry Into the Life & Death of the Master of Gonzo Warren Hinckle, founder of Ramparts, is a noted Bay Area author and journalist. He ISBN: 0-86719-648-3 shared an office with Hunter Thompson MARKETING $19.95 | paper throughout the 70’s and 80’s in a space I upstairs at the O’Farrell Theater, one of the consumer advertising, reviews 6 x 9 and features in national, 200 pages most famous erotic dance clubs in alternative and pop culture media June the country. -

A Genealogist Reveals the Painful Truth About Three Holocaust Memoirs: They’Re Fiction

discrepancies among names and dates in different translations helped to reveal the author’s true identity. A genealogist reveals the painful truth about three Holocaust memoirs: they’re fiction Untrue Stories BY cAleB dAniloff Detractors have called Sharon Sergeant a witch-hunter, a Holocaust denier, and even a Nazi. 32 BOSTONIA Summer 2009 PHOTograph by vernon doucette Summer 2009 BOSTONIA 33 In her 1997 autobiography, Misha: A Memoire The tools of her profession include photographic timelines and data- of the Holocaust Years, Belgian-born Misha bases — vital records, census reports, Defonseca claimed to have trekked war- property deeds, maps, newspaper interviews, obituaries, phone direc- pocked Europe for four years, starting at the tories — and living relatives. Skype, online records, and blogs have also age of seven, in search of her deported Jewish broadened her reach, and DNA testing parents. Along the way, she wrote, she took up is an option if she needs it. “The generic view of genealogy with a pack of wolves, slipped in and out of the is that it is about tracing relatives, the ‘begats,’” says Sergeant, a board Warsaw Ghetto, and killed a Nazi soldier. member and former programs director with the Massachusetts Genealogical In Europe, the book was a smash, court’s decision by proving the author Council. “It’s evolved.” translated into eighteen languages was a fraud. But her involvement in cracking and made into a hit film. In the It was there online, one day in open three Holocaust hoaxes is about United States, however, it had sold December 2007, that Sharon Sergeant more than an interest in the latest poorly — so poorly that Defonseca (MET’83), now an adjunct faculty technology.