Physician Participation in Executions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feminine Style in the Pursuit of Political Power

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Talk “Like a Man”: Feminine Style in the Pursuit of Political Power DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Political Science by Jennifer J. Jones Dissertation Committee: Professor Kristen Monroe, Chair Professor Marty Wattenberg Professor Michael Tesler 2017 Chapter 4 c 2016 American Political Science Association and Cambridge University Press. Reprinted with permission. All other materials c 2017 Jennifer J. Jones TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES iv LIST OF TABLES vi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vii CURRICULUM VITAE viii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION xi 1 Introduction 1 2 Theoretical Framework and Literature Review 5 2.1 Social Identity and Its Effect on Social Cognition . 6 2.1.1 Stereotypes and Expectations . 9 2.1.2 Conceptualizing Gender in US Politics . 13 2.2 Gender and Self-Presentation in US Politics . 16 2.2.1 Masculine Norms of Interaction in Institutional Settings . 16 2.2.2 Political Stereotypes and Leadership Prototypes . 18 2.3 The Impact of Political Communication in Electoral Politics . 22 2.4 Do Women Have to Talk Like Men to Be Considered Viable Leaders? . 27 3 Methods: Words are Data 29 3.1 Approaches to Studying Language . 30 3.2 Analyzing Linguistic Style . 34 3.2.1 Gendered Communication and the Feminine/Masculine Ratio . 37 3.2.2 Comparison with Other Coding Schemes . 39 3.3 Approaches to Studying Social Perception and Attitudes . 40 3.3.1 The Link Between Linguistic Style and Implicit Associations . 42 4 The Linguistic Styles of Hillary Clinton, 1992–2013 45 4.1 The Case of Hillary Clinton . -

Mels Resume:Update2020

Melissa Street Makeup Artist Film/Television/Theater/Live Events cell: (858) 344-7201 email: [email protected] FILM: 2020 MAKEUP DEPARTMENT HEAD - GIGI - Director: Drew Sackheim. 2018 MAKEUP ARTIST - TOP GUN MAVERICK - PARAMOUNT - Director: Joseph Kosinski - Starring: Tom Cruise, Jennifer Connelly, Jon Hamm, Val Kilmer, Miles Teller. 2016 MAKEUP DEPARTMENT HEAD - THE RIDE - 100 ACRE FILMS - SHORT FILM - Director: Eric Addison 2014 MAKEUP DEPARTMENT HEAD - WALTER - ZERO GRAVITY Director: Anna Mastro - Starring: Andrew J. West, Virginia Madsen, William H. Macy, Leven Rambin, Peter Facinelli, Neve Campbell, Brian White, Jim Gaffigan, Justin Kirk, Milo Ventimiglia. Personal artist to: Virginia Madsen, William H. Macy, Andrew J. West, Peter Facinelli, Neve Campbell, Brian White. 2013 MAKEUP DEPARTMENT HEAD - SUPER ATHLETE - WHITE NIGHT PRODUC- TIONS Director: John Comrie - Starring: Tony Sirico, Christopher Lloyd, Faran Tahir, Cameron Rodriguez, Larry Van- Buren Jr. Personal artist to: Tony Sirico, Christopher Lloyd, Faran Tahir. 2011 KEY MAKEUP ARTIST - WHEN YOU FIND ME - SHORT FILM - PROJECT IMAG- IN8TION/FREESTYLE Director: Bryce Dallas-Howard - Starring: Marianna Palka, Erin Way, Jacy King, Karley Scott Collins, Devon Woods, Zachary James Rukavina. 2010 MAKEUP DEPARTMENT HEAD - THE HEIRESS LETHAL - SHORT FILM - EYE- FULL STUDIOS Director: Michael Brueggemeyer - Starring: Merrick McCartha, Cristyn Chandler, Ron Christopher Jones, Theresa Layne. 2003 MAKEUP DEPARTMENT HEAD - CARROT TOP ROCKS LAS VEGAS - DELTA EN- TERTAINMENT Director: Steve Hanft - Starring: Scott “Carrot Top” Thompson, Penn Jillette, Teller. 1986 UNCREDITED MAKEUP ASSISTANT - INVADERS FROM MARS - CANNON PIC- TURES Director: Tobe Hooper - Starring: Karen Black, Hunter Carson, Timothy Bottoms, James Karen, Laraine Newman. Makeup Assistant to Stan Winston F/X lab team. -

Journalists Denying Liberal Bias, Part Three

Journalists Denying Liberal Bias, Part Three More examples of journalists denying their liberal bias: "I'm not going to judge anybody else in the business, but our work — I can speak for NBC News and our newsroom — it goes through, talk about checks and balances. We have an inordinate number of editors. Every word I write, before it goes on air, goes through all kinds of traps and filters, and it's read by all kinds of different people who point out bias." — CNBC anchor Brian Williams on Comedy Central's The Daily Show, July 29, 2003. "Our greatest accomplishment as a profession is the development since World War II of a news reporting craft that is truly non-partisan, and non-ideological....It is that legacy we must protect with our diligent stewardship. To do so means we must be aware of the energetic effort that is now underway to convince our readers that we are ideologues. It is an exercise of, in disinformation, of alarming proportions, this attempt to convince the audience of the world's most ideology-free newspapers that they're being subjected to agenda-driven news reflecting a liberal bias. I don't believe our viewers and readers will be, in the long-run, misled by those who advocate biased journalism." — New York Times Executive Editor Howell Raines accepting the 'George Beveridge Editor of the Year Award,' February 20, 2003. CBS's Lesley Stahl: "Today you have broadcast journalists who are avowedly conservative.... The voices that are being heard in broadcast media today, are far more likely to be on the right and avowedly so, and therefore, more — almost stridently so, than what you're talking about." Host Cal Thomas: "Can you name a conservative journalist at CBS News?" Stahl: "I don't know of anybody's political bias at CBS News....We try very hard to get any opinion that we have out of our stories, and most of our stories are balanced." — Exchange on the Fox News Channel's After Hours with Cal Thomas, January 18, 2003. -

King of the Paranormal

King of the Paranormal CNN's Larry King Live has a long history of outrageous promotion of UFOs, psychics, and spiritualists. CHRIS MOONEY roadcast on CNN, the July 1, 2003, installment of Larry King Live was a sight to behold. The program, Bin Kings words, explored "the incredible events of fifty-six years ago at Roswell, New Mexico." What most likely crashed at Roswell in 1947 was a government spy bal- loon, but the panel of guests assembled on King's show pre- ferred a more sensational version of events. Jesse Marcel, Jr., son of a Roswell intelligence officer, claimed that just after the crash, his father showed him bits of debris that "came from another civilization" (Marcel 2003). Glenn Dennis, who worked at a Roswell funeral home at the time, said a military officer called him to ask about the availability of small caskets (i.e., for dead aliens). Later Dennis, obviously SKEPTICAL INQUIRER November/December 2003 a UFO enthusiast, abruptly observed that the pyramids in Roswell crash site. Doleman admitted to King rJiat his dig had Egypt had recently been "[shut down] for three or four days not yet yielded any definitive evidence, but added that the and no tourists going out there on account of the sightings" "results" of his analysis will air on Sci-Fi in October—as (Dennis 2003). opposed to, say, being published in a peer-reviewed scientific King's program didn't merely advance the notion that an journal (Doleman 2003). [See also David E. Thomas, "Bait alien spacecraft crashed at Roswell in 1947. -

PAJ77/No.03 Chin-C

AIN’T NO SUNSHINE The Cinema in 2003 Larry Qualls and Daryl Chin s 2003 came to a close, the usual plethora of critics’ awards found themselves usurped by the decision of the Motion Picture Producers Association of A America to disallow the distribution of screeners to its members, and to any organization which adheres to MPAA guidelines (which includes the Motion Picture Academy of Arts and Sciences). This became the rallying cry of the Independent Feature Project, as those producers who had created some of the most notable “independent” films of the year tried to find a way to guarantee visibility during award season. This issue soon swamped all discussions of year-end appraisals, as everyone, from critics to filmmakers to studio executives, seemed to weigh in with an opinion on the matter of screeners. Yet, despite this media tempest, the actual situation of film continues to be precarious. As an example, in the summer of 2003 the distribution of films proved even more restrictive, as theatres throughout the United States were block-booked with the endless cycle of sequels that came from the studios (Legally Blonde 2, Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle, Terminator 3, The Matrix Revolutions, X-2: X-Men United, etc.). A number of smaller films, such as the nature documentary Winged Migration and the New Zealand coming-of-age saga Whale Rider, managed to infiltrate the summer doldrums, but the continued conglomeration of distribution and exhibition has brought the motion picture industry to a stultifying crisis. And the issue of the screeners was the rallying cry for those working on the fringes of the industry, the “independent” producers and directors and small distributors. -

Russell Brand

Russell Brand Arena-level stand-up that asks us to think as well as laugh The Guardian Awards: • Winner: British Comedy Awards: Outstanding Contribution To Comedy 2011 • Winner: British Comedy Awards: Best Live Stand-Up 2008 • Winner: Television and Radio Awards: Best Television Performer in a Non-Acting Role • Winner: British Comedy Awards: Best Newcomer 2006 • Winner: Loaded Laftas: Best Stand-Up 2006 • Winner: Time Out: Best Stand-Up 2006 Russell Brand is an award-winning comedian, writer, actor and presenter. Russell initially rose to fame in 2003 for his work as a presenter on MTV and on Big Brother spin-off, Big Brother’s Big Mouth. Since then he has become one of the most recognisable and best-loved comedy performers in the world, with a series of sold-out tours, bestselling DVDs and a number of major film roles to his name. His first nationwide stand-up tour, 2006’s Shame, was a huge success, eventually being filmed at London’s iconic Shepherd’s Bush Empire and released as a bestselling DVD, entitled Russell Brand: Live. He followed that tour with 2007’s Only Joking (released on DVD as Doin’ Life) and in 2009 embarked on his debut series of US dates with Scandalous. His most recent stand-up show, 2013’s critically–acclaimed Messiah Complex, was also a major hit and again a bestselling DVD. Russell has enjoyed a wide-ranging and incredibly successful career in UK television. After concluding his stint on Big Brother’s Big Mouth in 2007, he went on to host his own chat shows, MTV’s 1 Leicester Square and Channel 4’s The Russell Brand Show, as well as the Bafta-nominated Ponderland, also for Channel 4. -

Note Available from Pub Type Descriptors Abstract

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 357 176 CE 063 506 AUTHOR Hayes, Holly, Ed.; Marmolejo, Jill, Ed. TITLE Bee a Reader. INSTITUTION Fresno Bee, CA. PUB DATE Jun 89 NOTE 158p. AVAILABLE FROM Fresno Bee, 1626 E Street, Fresno, CA 93786-0001 (free). PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adult Basic Education; *Adult Literacy;Adult Reading Programs; Behavioral Objectives; Instructional Materials; Learning Activities; *Literacy Education; *Newspapers; *Reading Instruction; Teaching Guides; Vocabulary Development IDENTIFIERS *Fresno Bee ABSTRACT This publication is a tutor's guide to teaching basic literacy using The Fresno Bee, a Californianewspaper, as the primary "textbook." The course is aimed at English-speakingadults and is designed to teach reading in an interesting and entertainingway that promotes self-motivated study, both in the classroom andat home. The guide is divided into three parts, each with 25 lessons.Designed for the nonreader who knows almost nothing about language, noteven the sounds of the letters, Part I begins with letters andsounds and introduces students to the reading of basic words. The printedand cursive alphabets are introduced, along with the conceptof alphabetization. Designed for students who havesome knowledge of sounds and words, either through pretutoringor folloaing the lessons in Part I, Part II begins with a review of theletters and sounds, then moves into longer words, basic sentence structure,and basic punctuation. Designed for students who havesome basic reading ability but whneed vocabulary practice and work on practical reading, Part III begins with a review of the conceptscovered in Parts I and II and then continues withmore vocabulary development and practical reading: more on alphabetization, using advertising, reading maps, using indexes, categorization, writing basicletters, and filling out forms. -

A Nonverbal Signal in Voices of Interview Partners Effectively Predicts Communication Accommodation and Social Status Perceptions

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology Copyright 1996 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 1996, Vol. 70, No. 6, 1231-1240 0022-3514/96/$3.00 A Nonverbal Signal in Voices of Interview Partners Effectively Predicts Communication Accommodation and Social Status Perceptions Stanford W. Gregory, Jr. and Stephen Webster Kent State University Derivations from nonverbal communications accommodation theory are tested, and this knowledge is extended both theoreticallyand methodologically. Fast fourier transform and statistical analysis of a low-frequency nonverbal signal in voices from 25 dyadic interviews between a talk show host and his guests revealed voice convergence between partners. Correlation coefficients from comparisons of partners' voice spectra and factor analysis of the correlation matrix showed that lower status partners accommodated their voices to higher status partners via the nonverbal signal. Student rat- ings of the social status of the same talk show host and guests were correlated with factor loadings, thereby providing convergent validity of the nonverbal signal as a predictor of social status percep- tions and accommodation. Howard Giles's theories of speech convergence (Giles, 1973 ) Hodgins, & Miyake, 1990; Zuckerman & Miyake, 1993), atti- and accommodation (Giles & Smith, 1979) refer, respectively, tudes (Argyle, Alkema, & Gilmour, 1971; Woodall & Burgoon, to various processes whereby people shift their speech styles to 1983), and emotions (Burns & Beier, 1973; Helfrich & Wall- become more like those with whom they are interacting and to bott, 1986; Trimboli & Walker, 1987). ways in which people adapt their speech to how they believe An area of the research literature directly impinging on the others in the situation may best receive it. -

History Early History

Cable News Network, almost always referred to by its initialism CNN, is a U.S. cable newsnetwork founded in 1980 by Ted Turner.[1][2] Upon its launch, CNN was the first network to provide 24-hour television news coverage,[3] and the first all-news television network in the United States.[4]While the news network has numerous affiliates, CNN primarily broadcasts from its headquarters at the CNN Center in Atlanta, the Time Warner Center in New York City, and studios in Washington, D.C. and Los Angeles. CNN is owned by parent company Time Warner, and the U.S. news network is a division of the Turner Broadcasting System.[5] CNN is sometimes referred to as CNN/U.S. to distinguish the North American channel from its international counterpart, CNN International. As of June 2008, CNN is available in over 93 million U.S. households.[6] Broadcast coverage extends to over 890,000 American hotel rooms,[6] and the U.S broadcast is also shown in Canada. Globally, CNN programming airs through CNN International, which can be seen by viewers in over 212 countries and territories.[7] In terms of regular viewers (Nielsen ratings), CNN rates as the United States' number two cable news network and has the most unique viewers (Nielsen Cume Ratings).[8] History Early history CNN's first broadcast with David Walkerand Lois Hart on June 1, 1980. Main article: History of CNN: 1980-2003 The Cable News Network was launched at 5:00 p.m. EST on Sunday June 1, 1980. After an introduction by Ted Turner, the husband and wife team of David Walker and Lois Hart anchored the first newscast.[9] Since its debut, CNN has expanded its reach to a number of cable and satellite television networks, several web sites, specialized closed-circuit networks (such as CNN Airport Network), and a radio network. -

Monitoring Report I=Interview; GR=Graphic; PC=Press Conference; R=Reader; SI=Studio Interview; T=Teaser; TZ=Teased Segment; V=Visual

Monitoring Report I=Interview; GR=Graphic; PC=Press Conference; R=Reader; SI=Studio Interview; T=Teaser; TZ=Teased Segment; V=Visual CDC 09/11 to 11/01 1. Nightline ABC Network National 10/12/2001 11:35 - 12:05 am Estimated Audience: 4,997,900 15.37 TZ; More Terrorism. They continue their discussion about anthrax and bioterrorism. SI; Dr. Jeffrey Koplan, CDC Director, says they received a call from the New York City Health Department involving the NBC employee. Koplan says the woman was exposed to the contents of an ill intentioned letter and developed a skin rash and lesion. Koplan says the amount of powder matters when trying to determine if it is anthrax. Koplan says the health agencies have a done a good job in determining the cases quickly. Koplan says there is no reason for anyone to get a nasal swab at this time. 21.42 2. Good Morning America ABC Network National 10/15/2001 7:00 - 8:00 am Estimated Audience: 4,660,780 08.23 TZ; Anthrax. America was preparing for an anthrax attack. Everybody at NBC wants to be tested. SI; Dr. Stephen Ostroff, CDC, says we know that anthrax doesn't widely disperse itself. Ostroff says they've been very precautionary, gathering info & testing everybody that was on the floor where the letter may have been present. GR; Photos of anthrax cases. GR; Inhalation Anthrax. 13.04 3. Good Morning America ABC Network National 10/16/2001 7:00 - 8:00 am Estimated Audience: 4,660,780 14.50 TZ; Anthrax Analysis. -

Star Channels, June 20

JUNE 20 - 26, 2021 staradvertiser.com DESPERATE HOUSEWIFE Emmy winner Annie Murphy returns to television as Allison, a long-suffering sitcom wife who suddenly realizes she no longer wants to be the butt of her oafi sh husband’s jokes in Kevin Can F**K Himself. Billed as a “dark dramedy,” the unique series switches between a saccharine sitcom world and one in which Allison plots against her husband. Premiering Sunday, June 20, on AMC. ST JULY 1 SECOND SEASON Mele A‘e VIRTUAL AUDITION THE NEXT PERFORMANCE COULD BE YOURS. DEADLINE IS SUBMIT YOUR VIRTUAL AUDITION NOW! This is your chance to break through. Mele A¶e is a new program from ¶ũe^ehmaZmlahp\Zl^lAZpZb¶blg^qm`^g^kZmbhgh_fnlb\ZeZkmblml'?bef^]hg¶ũe^ehllmZm^&h_&ma^&Zkm olelo.org lhng]lmZ`^%Lmn]bh**++%l^e^\m^]Zkmblmlpbeei^k_hkfma^bkhpghkb`bgZelhg`l'Oblbmolelo.org/auditions 590228_MeleAe_Season2wDeadline_2in_F.indd 1 5/6/21 10:59 AM ON THE COVER | THE 48TH ANNUAL DAYTIME EMMY AWARDS Going for gold ‘The 48th Annual Daytime Bold and the Beautiful,” “Days of Our Lives” This year’s Daytime Emmys will also honor and “The Young and the Restless” have each TV legends Alex Trebek (“Jeopardy”) and Larry Emmy Awards’ airs on CBS received nominations in multiple categories, King (“Larry King Live”), both of whom died including all of them for Outstanding Drama within the last year and received posthumous Series. Overall, more than 40 categories are nominations. By Rachel Jones represented. Trebek, who died from pancreatic cancer TV Media But with 16 nominations for acting alone, at his home last November, is nominated for “General Hospital” still trumps every other Outstanding Game Show Host. -

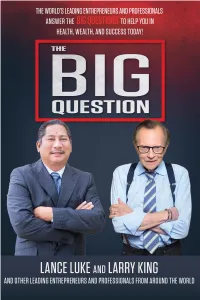

THE BIG QUESTION to Them

Copyright © 2018 CelebrityPress® LLC All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without prior written consent of the author, except as provided by the United States of America copyright law Published by CelebrityPress®, Orlando, FL. CelebrityPress® is a registered trademark. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN: 978-0-9991714-5-5 LCCN: 2018931599 This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information with regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional advice. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought. The opinions expressed by the authors in this book are not endorsed by CelebrityPress® and are the sole responsibility of the author rendering the opinion. Most CelebrityPress® titles are available at special quantity discounts for bulk purchases for sales promotions, premiums, fundraising, and educational use. Special versions or book excerpts can also be created to fit specific needs. For more information, please write: CelebrityPress® 520 N. Orlando Ave, #2 Winter Park, FL 32789 or call 1.877.261.4930 Visit us online at: www.CelebrityPressPublishing.com CelebrityPress® Winter Park, Florida CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 QUESTIONS ARE MORE IMPORTANT THAN ANSWERS By Larry King .................................................................................... 13 CHAPTER 2 PUBLIC SPEAKING: HOW TO ACHIEVE MAXIMUM AUDIENCE ENGAGEMENT By Mohamed Isa .............................................................................. 23 CHAPTER 3 THE INTERVIEW THAT, SADLY, NEVER WAS By John Parks Trowbridge M.D., FACAM ..........................................31 CHAPTER 4 WHY DO THE BIG GET BIGGER? By Rebecca Crownover ...................................................................47 CHAPTER 5 THE KEYS TO SUCCESS By Patricia Delinois ..........................................................................