Trichinellosis Surveillance — United States, 2002–2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trichinosis (Trichinellosis) Case Reporting and Investigation Protocol

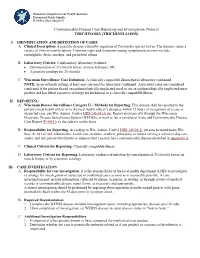

Wisconsin Department of Health Services Division of Public Health P-01912 (Rev 08/2017) Communicable Disease Case Reporting and Investigation Protocol TRICHINOSIS (TRICHINELLOSIS) I. IDENTIFICATION AND DEFINITION OF CASES A. Clinical Description: A parasitic disease caused by ingestion of Trichinella species larvae. The disease causes a variety of clinical manifestations. Common signs and symptoms among symptomatic persons include eosinophilia, fever, myalgia, and periorbital edema. B. Laboratory Criteria: Confirmatory laboratory evidence: • Demonstration of Trichinella larvae on muscle biopsy, OR • A positive serology for Trichinella. C. Wisconsin Surveillance Case Definition: A clinically compatible illness that is laboratory confirmed. NOTE: In an outbreak setting, at least one case must be laboratory confirmed. Associated cases are considered confirmed if the patient shared an epidemiologically implicated meal or ate an epidemiologically implicated meat product and has either a positive serology for trichinosis or a clinically compatible illness. II. REPORTING A. Wisconsin Disease Surveillance Category II – Methods for Reporting: This disease shall be reported to the patient’s local health officer or to the local health officer’s designee within 72 hours of recognition of a case or suspected case, per Wis. Admin. Code § DHS 145.04 (3) (b). Report electronically through the Wisconsin Electronic Disease Surveillance System (WEDSS), or mail or fax a completed Acute and Communicable Disease Case Report (F-44151) to the address on the form. B. Responsibility for Reporting: According to Wis. Admin. Code § DHS 145.04(1), persons licensed under Wis. Stat. ch. 441 or 448, laboratories, health care facilities, teachers, principals, or nurses serving a school or day care center, and any person who knows or suspects that a person has a communicable disease identified in Appendix A. -

Onchocerciasis

11 ONCHOCERCIASIS ADRIAN HOPKINS AND BOAKYE A. BOATIN 11.1 INTRODUCTION the infection is actually much reduced and elimination of transmission in some areas has been achieved. Differences Onchocerciasis (or river blindness) is a parasitic disease in the vectors in different regions of Africa, and differences in cause by the filarial worm, Onchocerca volvulus. Man is the the parasite between its savannah and forest forms led to only known animal reservoir. The vector is a small black fly different presentations of the disease in different areas. of the Simulium species. The black fly breeds in well- It is probable that the disease in the Americas was brought oxygenated water and is therefore mostly associated with across from Africa by infected people during the slave trade rivers where there is fast-flowing water, broken up by catar- and found different Simulium flies, but ones still able to acts or vegetation. All populations are exposed if they live transmit the disease (3). Around 500,000 people were at risk near the breeding sites and the clinical signs of the disease in the Americas in 13 different foci, although the disease has are related to the amount of exposure and the length of time recently been eliminated from some of these foci, and there is the population is exposed. In areas of high prevalence first an ambitious target of eliminating the transmission of the signs are in the skin, with chronic itching leading to infection disease in the Americas by 2012. and chronic skin changes. Blindness begins slowly with Host factors may also play a major role in the severe skin increasingly impaired vision often leading to total loss of form of the disease called Sowda, which is found mostly in vision in young adults, in their early thirties, when they northern Sudan and in Yemen. -

Tissue Nematode: Trichenella Spiralis

Tissue nematode: Trichenella spiralis Introduction Trichinella spiralis is a viviparous nematode parasite, occurring in pigs, rodents, bears, hyenas and humans, and is liable for the disease trichinosis. It is occasionally referred to as the "pork worm" as it is characteristically encountered in undercooked pork foodstuffs. It should not be perplexed with the distantly related pork tapeworm. Trichinella species, the small nematode parasite of individuals, have an abnormal lifecycle, and are one of the most extensive and clinically significant parasites in the whole world. The adult worms attain maturity in the small intestine of a definitive host, such as pig. Each adult female gives rise to batches of live larvae, which bore across the intestinal wall, enter the blood stream (to feed on it) and lymphatic system, and are passed to striated muscle. Once reaching to the muscle, they encyst, or become enclosed in a capsule. Humans can become infected by eating contaminated pork, horse meat, or wild carnivorus animals such as cat, fox, or bear. Epidemology Trichinosis is a disease caused by the worm. It occurs around most parts of the world, and infects majority of humans. It ranges from North America and Europe, to Japan, China and Tropical Africa. Morphology Males of T. spiralis measure about1.4 and 1.6 mm long, and are more flat at anterior end than posterior end. The anus is seen in the terminal position, and they have a large copulatory pseudobursa on both the side. The females of T. spiralis are nearly twice the size of the males, and have an anal aperture situated terminally. -

STUDY of PARASITIC INFESTATION and ITS EFFECT on the HEALTH STATUS of PRIMARY SCHOOL CHILDREN in TANTA CITY Nour Abd El Azize Mohammed Mealy, Prof

STUDY OF PARASITIC INFESTATION AND ITS EFFECT ON THE HEALTH STATUS OF PRIMARY SCHOOL CHILDREN IN TANTA CITY Nour Abd El Azize Mohammed Mealy, Prof. Dr. Nadia Yahia Ismaiel, Prof. Dr. Hassan Saad Abu Saif, Prof. Dr. Wael Refaat Hablas STUDY OF PARASITIC INFESTATION AND ITS EFFECT ON THE HEALTH STATUS OF PRIMARY SCHOOL CHILDREN IN TANTA CITY By Nour Abd El Azize Mohammed Mealy, Prof. Dr. Nadia Yahia Ismaiel*, Prof. Dr. Hassan Saad Abu Saif*, Prof. Dr. Wael Refaat Hablas** Pediatric*& Clinical Pathology** Depts. Al-Azhar University- Faculty of Medicine ABSTRACT Background: School age children are one of the groups at high-risk for intestinal parasitic infestations. Factors like poor developments of hygienic habits, immune system and over-crowding contributes for infestation. The adverse effects of intestinal parasites among children are diverse and alarming. Intestinal parasitic infestations have detrimental effects on the survival, appetite, growth and physical fitness, school attendance and cognitive performance of school age children (Alemu et al., 2011). Objectives: We aimed to 1. Assess the prevalence of parasitic infestation and its effect on the health status of primary school children in Tanta City (5 schools from 3 areas at Tanta city) 2. Determine the prevalence of intestinal parasitic infestation among primary school children in some urban communities of Tanta City 3. Identify associated risk factors of school children for parasitic infestations in some urban communities of Tanta City. Design: This is descriptive cross sectional study that was carried out on 1000 students (boys &girls) at governmental primary schools at Tanta rural areas. This research was continued until fulfillment of the study from April 2017 to May 2018. -

New Aspects of Human Trichinellosis: the Impact of New Trichinella Species F Bruschi, K D Murrell

15 REVIEW Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pmj.78.915.15 on 1 January 2002. Downloaded from New aspects of human trichinellosis: the impact of new Trichinella species F Bruschi, K D Murrell ............................................................................................................................. Postgrad Med J 2002;78:15–22 Trichinellosis is a re-emerging zoonosis and more on anti-inflammatory drugs and antihelminthics clinical awareness is needed. In particular, the such as mebendazole and albendazole; the use of these drugs is now aided by greater clinical description of new Trichinella species such as T papuae experience with trichinellosis associated with the and T murrelli and the occurrence of human cases increased number of outbreaks. caused by T pseudospiralis, until very recently thought to The description of new Trichinella species, such as T murrelli and T papuae, as well as the occur only in animals, requires changes in our handling occurrence of outbreaks caused by species not of clinical trichinellosis, because existing knowledge is previously recognised as infective for humans, based mostly on cases due to classical T spiralis such as T pseudospiralis, now render the clinical picture of trichinellosis potentially more compli- infection. The aim of the present review is to integrate cated. Clinicians and particularly infectious dis- the experiences derived from different outbreaks around ease specialists should consider the issues dis- the world, caused by different Trichinella species, in cussed in this review when making a diagnosis and choosing treatment. order to provide a more comprehensive approach to diagnosis and treatment. SYSTEMATICS .......................................................................... Trichinellosis results from infection by a parasitic nematode belonging to the genus trichinella. -

Public Health Significance of Intestinal Parasitic Infections*

Articles in the Update series Les articles de la rubrique give a concise, authoritative, Le pointfournissent un bilan and up-to-date survey of concis et fiable de la situa- the present position in the tion actuelle dans les do- Update selectedfields, coveringmany maines consideres, couvrant different aspects of the de nombreux aspects des biomedical sciences and sciences biomedicales et de la , po n t , , public health. Most of santepublique. Laplupartde the articles are written by ces articles auront donc ete acknowledged experts on the redigeis par les specialistes subject. les plus autorises. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 65 (5): 575-588 (1987) © World Health Organization 1987 Public health significance of intestinal parasitic infections* WHO EXPERT COMMITTEE' Intestinal parasitic infections are distributed virtually throughout the world, with high prevalence rates in many regions. Amoebiasis, ascariasis, hookworm infection and trichuriasis are among the ten most common infections in the world. Other parasitic infections such as abdominal angiostrongyliasis, intestinal capil- lariasis, and strongyloidiasis are of local or regional public health concern. The prevention and control of these infections are now more feasible than ever before owing to the discovery of safe and efficacious drugs, the improvement and sim- plification of some diagnostic procedures, and advances in parasite population biology. METHODS OF ASSESSMENT The amount of harm caused by intestinal parasitic infections to the health and welfare of individuals and communities depends on: (a) the parasite species; (b) the intensity and course of the infection; (c) the nature of the interactions between the parasite species and concurrent infections; (d) the nutritional and immunological status of the population; and (e) numerous socioeconomic factors. -

Public Health Significance of Foodborne

imental er Fo p o x d E C Journal of Experimental Food f h o e l m a n i Pal et al., J Exp Food Chem 2018, 4:1 s r t u r y o J Chemistry DOI: 10.4172/2472-0542.1000135 ISSN: 2472-0542 Review Article Open Access Public Health Significance of Foodborne Helminthiasis: A Systematic Review Mahendra Pal1*, Yodit Ayele2, Angesom Hadush3, Pooja Kundu4 and Vijay J Jadhav4 1Narayan Consultancy on Veterinary Public Health, 4 Aangan, Jagnath Ganesh Dairy Road, Anand-38001, India 2Department of Animal Science, College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Bonga University, Post Box No.334, Bonga, Ethiopia 3Department of Animal Production and Technology, College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences, Adigrat University, P.O. Box 50, Adigrat, Ethiopia 4Department of Veterinary Public Health and Epidemiology, College of Veterinary Sciences, LUVAS, Hisar-125004, India *Corresponding author: Mahendra Pal, Narayan Consultancy on Veterinary Public Health and Microbiology, 4 Aangan, Jagnath Ganesh Dairy Road, Anand-388001, Gujarat, India, E-mail: [email protected] Received date: December 18, 2017; Accepted date: January 19, 2018; Published date: January 25, 2018 Copyright: ©2017 Pal M, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Foodborne diseases, caused by biological as well as chemical agents, have an impact in both developing and developed nations. The foodborne diseases of microbial origin are acute where as those caused by chemical toxicants are resulted due to chronic exposure. -

Trichinella Nativa in a Black Bear from Plymouth, New Hampshire

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty Research Service, Lincoln, Nebraska 2005 Trichinella nativa in a black bear from Plymouth, New Hampshire D.E. Hill Animal Parasitic Diseases Laboratory, [email protected] H.R. Gamble National Academy of Sciences, Washington D.S. Zarlenga Animal Parasitic Diseases Laboratory & Bovine Functions and Genomics Laboratory C. Cross Animal Parasitic Diseases Laboratory J. Finnigan New Hampshire Public Health Laboratories, Concord Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdaarsfacpub Hill, D.E.; Gamble, H.R.; Zarlenga, D.S.; Cross, C.; and Finnigan, J., "Trichinella nativa in a black bear from Plymouth, New Hampshire" (2005). Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty. 2244. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdaarsfacpub/2244 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Research Service, Lincoln, Nebraska at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Veterinary Parasitology 132 (2005) 143–146 www.elsevier.com/locate/vetpar Trichinella nativa in a black bear from Plymouth, New Hampshire D.E. Hill a,*, H.R. Gamble c, D.S. Zarlenga a,b, C. Coss a, J. Finnigan d a United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Animal and Natural Resources Institute, Animal Parasitic Diseases Laboratory, Building 1044, BARC-East, Beltsville, MD 20705, USA b Bovine Functions and Genomics Laboratory, Building 1044, BARC-East, Beltsville, MD 20705, USA c National Academy of Sciences, Washington, DC, USA d The Food Safety Microbiology Unit, New Hampshire Public Health Laboratories, Concord, NH, USA Abstract A suspected case of trichinellosis was identified in a single patient by the New Hampshire Public Health Laboratories in Concord, NH. -

Imaging Parasitic Diseases

Insights Imaging (2017) 8:101–125 DOI 10.1007/s13244-016-0525-2 REVIEW Unexpected hosts: imaging parasitic diseases Pablo Rodríguez Carnero1 & Paula Hernández Mateo2 & Susana Martín-Garre2 & Ángela García Pérez3 & Lourdes del Campo1 Received: 8 June 2016 /Revised: 8 September 2016 /Accepted: 28 September 2016 /Published online: 23 November 2016 # The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Radiologists seldom encounter parasitic dis- • Some parasitic diseases are still endemic in certain regions eases in their daily practice in most of Europe, although in Europe. the incidence of these diseases is increasing due to mi- • Parasitic diseases can have complex life cycles often involv- gration and tourism from/to endemic areas. Moreover, ing different hosts. some parasitic diseases are still endemic in certain • Prompt diagnosis and treatment is essential for patient man- European regions, and immunocompromised individuals agement in parasitic diseases. also pose a higher risk of developing these conditions. • Radiologists should be able to recognise and suspect the This article reviews and summarises the imaging find- most relevant parasitic diseases. ings of some of the most important and frequent human parasitic diseases, including information about the para- Keywords Parasitic diseases . Radiology . Ultrasound . site’s life cycle, pathophysiology, clinical findings, diag- Multidetector computed tomography . Magnetic resonance nosis, and treatment. We include malaria, amoebiasis, imaging toxoplasmosis, trypanosomiasis, leishmaniasis, echino- coccosis, cysticercosis, clonorchiasis, schistosomiasis, fascioliasis, ascariasis, anisakiasis, dracunculiasis, and Introduction strongyloidiasis. The aim of this review is to help radi- ologists when dealing with these diseases or in cases Parasites are organisms that live in another organism at the where they are suspected. -

"Structure, Function and Evolution of the Nematode Genome"

Structure, Function and Advanced article Evolution of The Article Contents . Introduction Nematode Genome . Main Text Online posting date: 15th February 2013 Christian Ro¨delsperger, Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology, Tuebingen, Germany Adrian Streit, Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology, Tuebingen, Germany Ralf J Sommer, Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology, Tuebingen, Germany In the past few years, an increasing number of draft gen- numerous variations. In some instances, multiple alter- ome sequences of multiple free-living and parasitic native forms for particular developmental stages exist, nematodes have been published. Although nematode most notably dauer juveniles, an alternative third juvenile genomes vary in size within an order of magnitude, com- stage capable of surviving long periods of starvation and other adverse conditions. Some or all stages can be para- pared with mammalian genomes, they are all very small. sitic (Anderson, 2000; Community; Eckert et al., 2005; Nevertheless, nematodes possess only marginally fewer Riddle et al., 1997). The minimal generation times and the genes than mammals do. Nematode genomes are very life expectancies vary greatly among nematodes and range compact and therefore form a highly attractive system for from a few days to several years. comparative studies of genome structure and evolution. Among the nematodes, numerous parasites of plants and Strikingly, approximately one-third of the genes in every animals, including man are of great medical and economic sequenced nematode genome has no recognisable importance (Lee, 2002). From phylogenetic analyses, it can homologues outside their genus. One observes high rates be concluded that parasitic life styles evolved at least seven of gene losses and gains, among them numerous examples times independently within the nematodes (four times with of gene acquisition by horizontal gene transfer. -

61% of All Human Pathogens Are Zoonotic (Passed from Animals to Humans), and Many Are Transmitted Through Inhaling Dust Particles Or Contact with Animal Wastes

Zoonotic Diseases Fast Facts: 61% of all human pathogens are zoonotic (passed from animals to humans), and many are transmitted through inhaling dust particles or contact with animal wastes. Some of the diseases we can get from our pets may be fatal if they go undetected or undiagnosed. All are serious threats to human health, but can usually be avoided by observing a few precautions, the most effective of which is washing your hands after touching animals or their wastes. Regular visits to the veterinarian for prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of zoonotic diseases will help limit disease in your pet. Source: http://www.cdc.gov/healthypets/ Some common zoonotic diseases humans can get through their pets: Zoonotic Disease & its Effect on How Contact is Made Humans Bartonellosis (cat scratch disease) – an Bartonella bacteria are transferred to humans through infection from the bacteria Bartonella a bite or scratch. Do not play with stray cats, and henselae that causes fever and swollen keep your cat free of fleas. Always wash hands after lymph nodes. handling your cat. Capnocytophaga infection – an Capnocytophaga canimorsus is the main human infection caused by bacteria that can pathogen associated with being licked or bitten by an develop into septicemia, meningitis, infected dog and may present a problem for those and endocarditis. who are immunosuppressed. Cellulitis – a disease occurring when Bacterial organisms from the Pasteurella species live bacteria such as Pasteurella multocida in the mouths of most cats, as well as a significant cause a potentially serious infection of number of dogs and other animals. These bacteria the skin. -

Comparative Genomics of the Major Parasitic Worms

Comparative genomics of the major parasitic worms International Helminth Genomes Consortium Supplementary Information Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 4 Contributions from Consortium members ..................................................................................... 5 Methods .................................................................................................................................... 6 1 Sample collection and preparation ................................................................................................................. 6 2.1 Data production, Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute (WTSI) ........................................................................ 12 DNA template preparation and sequencing................................................................................................. 12 Genome assembly ........................................................................................................................................ 13 Assembly QC ................................................................................................................................................. 14 Gene prediction ............................................................................................................................................ 15 Contamination screening ............................................................................................................................