Questions Q1 Should a Period of Positive Prescription for Corporeal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

Case: 15-55550, 07/10/2017, ID: 10502017, DktEntry: 127-1, Page 1 of 61 FOR PUBLICATION UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT DAVID CASSIRER; AVA CASSIRER; No. 15-55550 UNITED JEWISH FEDERATION OF SAN 15-55977 DIEGO COUNTY, a California non- profit corporation, D.C. No. Plaintiffs-Appellees, 2:05-cv-03459- JFW-E v. THYSSEN-BORNEMISZA COLLECTION FOUNDATION, an agency or instrumentality of the Kingdom of Spain, Defendant-Appellant. DAVID CASSIRER; AVA CASSIRER; No. 15-55951 UNITED JEWISH FEDERATION OF SAN DIEGO COUNTY, a California non- D.C. No. profit corporation, 2:05-cv-03459- Plaintiffs-Appellants, JFW-E v. OPINION THYSSEN-BORNEMISZA COLLECTION FOUNDATION, an agency or instrumentality of the Kingdom of Spain, Defendant-Appellee. Case: 15-55550, 07/10/2017, ID: 10502017, DktEntry: 127-1, Page 2 of 61 2 CASSIRER V. THYSSEN-BORNEMISZA COLLECTION Appeal from the United States District Court for the Central District of California John F. Walter, District Judge, Presiding Argued and Submitted December 5, 2016 Pasadena, California Filed July 10, 2017 Before: Consuelo M. Callahan, Carlos T. Bea, and Sandra S. Ikuta, Circuit Judges. Opinion by Judge Bea Case: 15-55550, 07/10/2017, ID: 10502017, DktEntry: 127-1, Page 3 of 61 CASSIRER V. THYSSEN-BORNEMISZA COLLECTION 3 SUMMARY* Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act / Holocaust Expropriated Art Recovery Act The panel reversed the district court’s grant of summary judgment, on remand, in favor of Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection Foundation, the defendant in an action under the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act concerning a Camille Pissarro painting that was forcibly taken from the plaintiffs’ great-grandmother by an art dealer who had been appointed by the Nazi government to conduct an appraisal. -

Patent Transfer and the Bundle of Sticks

GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works Faculty Scholarship 2016 Patent Transfer And The Bundle of Sticks Andrew Michaels The George Washington University Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Michaels, Andrew C., Patent Transfer and the Bundle of Sticks (December 1, 2016). GWU Law School Public Law Research Paper No. 2016-57; GWU Legal Studies Research Paper No. 2016-57. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2883829 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Andrew C. Michaels Patent Transfer DRAFT – Dec. 2016 Patent Transfer And The Bundle of Sticks by Andrew C. Michaels* Abstract In the age of the patent troll, patents are often licensed and transferred. A transferred patent may have been subject to multiple complex license agreements. It cannot be that such a transfer wipes the patent clean of all outstanding license agreements; the licensee must keep the license. But at the same time, it cannot be that the patent transferee becomes a party to a complex and sweeping license agreement – the contract – merely by virtue of acquiring one patent. This article attempts to separate the in personam aspects of a license agreement from its effects on the underlying in rem patent rights, using Hohfeld’s framework of jural relations and the “bundle of sticks” conception of property. -

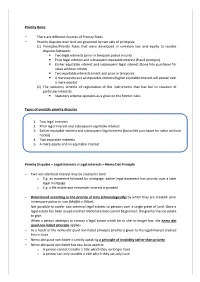

Priority Rules

Priority Rules − There are different Sources of Priority Rules − Priority disputes over land are governed by two sets of principles: (1) Principles/Priority Rules that were developed in common law and equity to resolve disputes between: ▪ Two legal interests (prior in tempore potior in iure) ▪ Prior legal interest and subsequent equitable interest (fraud principle) ▪ Earlier equitable interest and subsequent legal interest (bona fide purchaser for value without notice) ▪ Two equitable interests (merit and prior in tempore) ▪ A mere equity and an equitable interest (higher equitable interest will prevail over a mere equity) (2) The statutory scheme of registration of the instruments that has led to creation of particular interests: ▪ Statutory scheme operates as a gloss on the former rules Types of possible priority disputes 1. Two legal interests 2. Prior legal interest and subsequent equitable interest 3. Earlier equitable interest and subsequent legal interest (bona fide purchaser for value without notice) 4. Two equitable interests 5. A mere equity and an equitable interest Priority Disputes – Legal interests v Legal interests – Nemo Dat Principle − Two non-identical interest may be created in land o E.g. an easement followed by mortgage: earlier legal easement has priority over a later legal mortgage o E.g. a life estate and remainder interest is granted − Determined according to the priority of time (chronologically) by which they are created: prior in tempore potior in iure (Moffet v Dillon). − Not possible to confer two identical legal estates to persons over a single piece of land. Once a legal estate has been issued another identical estate cannot be granted: the grantor has no estate to give. -

![[1] the Basics of Property Division](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2246/1-the-basics-of-property-division-1212246.webp)

[1] the Basics of Property Division

RESTATEMENT OF THE LAW FOURTH, PROPERTY PROJECTED OVERALL TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME [1] THE BASICS OF PROPERTY DIVISION ONE: DEFINITIONS Chapter 1. Meanings of “Property” Chapter 2. Property as a Relation Chapter 3. Separation into Things Chapter 4. Things versus Legal Things Chapter 5. Tangible and Intangible Things Chapter 6. Contracts as Property [pointers to Contracts Restatement and UCC] Chapter 7. Property in Information [pointer to Intellectual Property Restatement(s)] Chapter 8. Entitlement and Interest Chapter 9. In Rem Rights Chapter 10. Residual Claims Chapter 11. Customary Rights Chapter 12. Quasi-Property DIVISION TWO: ACCESSION Chapter 13. Scope of Legal Thing Chapter 14. Ad Coelum Chapter 15. Airspace Chapter 16. Minerals Chapter 17. Caves Chapter 18. Accretion, etc. [cross-reference to water law, Vol. 2, Ch. 2] Chapter 19. Fruits, etc. Chapter 20. Fixtures Chapter 21. Increase Chapter 22. Confusion Chapter 23. Improvements DIVISION THREE: POSSESSION Chapter 24. De Facto Possession Chapter 25. Customary Legal Possession Chapter 26. Basic Legal Possession Chapter 27. Rights to Possess Chapter 28. Ownership versus Possession Chapter 29. Transitivity of Rights to Possess Chapter 30. Sequential Possession, Finders Chapter 31. Adverse Possession Chapter 32. Adverse Possession and Prescription Chapter 33. Interests Not Subject to Adverse Possession Chapter 34. State of Mind in Adverse Possession xvii © 2016 by The American Law Institute Preliminary draft - not approved Chapter 35. Tacking in Adverse Possession DIVISION FOUR: ACQUISITION Chapter 36. Acquisition by Possession Chapter 37. Acquisition by Accession Chapter 38. Specification Chapter 39. Creation VOLUME [2] INTERFERENCES WITH, AND LIMITS ON, OWNERSHIP AND POSSESSION Introductory Note (including requirements of possession) DIVISION ONE: PROPERTY TORTS Chapter 1. -

At the University of Edinburgh

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. THE PHYSICAL ELEMENT OF POSSESSION OF CORPOREAL MOVEABLE PROPERTY IN SCOTS LAW CRAIG ANDERSON Submitted for the degree of Ph.D. The University of Edinburgh 2014 1 ABSTRACT Possession is a legal concept applying in a variety of legal contexts. In Scottish legal literature, however, there is little in-depth writing on the law of possession, and much of the law is uncertain. This thesis is intended to be a contribution to remedying this deficiency as far as one aspect of the law of possession is concerned, the physical element of possession of corporeal moveable property. As part of this, in the hope that this comparative and historical consideration would shed some light on the issues raised, the law of Rome is considered, along with the law of France, Germany and South Africa, as examples of the Civil Law tradition of legal systems drawing on Roman law. -

Property Law: the Unsung Hero of North Sea Oil and Gas Author: Demetris Hadjiosif and Constantinos Yiallourides Source: the King’S Student Law Review, Vol

The King’s Student Law Review Title: Property Law: The Unsung Hero of North Sea Oil and Gas Author: Demetris Hadjiosif and Constantinos Yiallourides Source: The King’s Student Law Review, Vol. 5, No. 2 (Winter 2014), pp. 52-66 Published by: King’s College London on behalf of The King’s Student Law Review All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, or stored in any retrieval system of any nature, without the prior, express written permission of the King’s Student Law Review. Within the UK, exceptions are allowed in respect of any fair dealing for the purpose of research of private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act,1988. Enquiries concerning reproducing outside these terms and in other countries should be sent to the Editor in Chief. KSLR is an independent, not-for-profit, online academic publication managed by students of the King’s College London School of Law. The Review seeks to publish high-quality legal scholarship written by undergraduate and graduate students at King’s and other leading law schools across the globe. For more information about KSLR, please visit our website: http://www.kcl.ac.uk/law/about/review.aspx ©King’s Student Law Review 2014 PROPERTY LAW: THE UNSUNG HERO OF NORTH SEA OIL AND GAS Demetris Hadjiosif and Constantinos Yiallourides* The present paper examines the key property law-related issues pertaining to the development of subsea mineral resources on the United Kingdom Continental Shelf: from their initial ‘capture’ (acquisition of ownership) to their transportation to downstream facilities via onshore pipelines. -

Report on Prescription and Title to Moveable Property

(SCOT LAW COM No 228) Report on Prescription and Title to Moveable Property report Report on Prescription and Title to Moveable Property Laid before the Scottish Parliament by the Scottish Ministers May 2012 Updated to include corrections to pages vi, 44 and 45, May 2012 SCOT LAW COM No 228 SG/2012/77 EDINBURGH: The Stationery Office £16.00 © Crown copyright 2012 You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/ or email: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any copyright enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected]. ISBN: 978-0-10-888264-7 Printed in the UK for The Stationery Office Limited on behalf of the Queen’s Printer for Scotland. 05/12 Cover printed on 75% recycled paper Text printed on 100% recycled paper ii The Scottish Law Commission was set up by section 2 of the Law Commissions Act 19651 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law of Scotland. The Commissioners2 are: Laura J Dunlop, QC Patrick Layden, QC TD Professor Hector L MacQueen Dr Andrew J M Steven. The Chief Executive of the Commission is Malcolm McMillan. Its offices are at 140 Causewayside, Edinburgh EH9 1PR. Tel: 0131 668 2131 Fax: 0131 662 4900 Email: [email protected] Or via our website at http://www.scotlawcom.gov.uk/contact-us NOTES 1. -

Udal Law: an Introduction

UDAL LAW: AN INTRODUCTION lane Ryder, W.S. As a lecture delivered to the Scottish Society for Northern Studies, this article represented the writer's first attempts to wrestle with the vexed question of udal law in Orkney and Shetland. A comprehensive account, together with an editorial excursus by the late Sir Thomas Smith, has since been published in The Laws of Scotland: the Stair Memorial Encyclopaedia. 1 What the revised article attempts is a synthesis of the two entries in the Stair Encyclopaedia, in so far as they address issues of historical background, without necessarily examining every aspect of the law. The article also attempts to highlight issues of general interest in the context of modern United Kingdom law. With this in mind, it is useful to examine three distinct periods: the first being the period before the pledging or wadset ofthe islands in 1468-9, the second period from 1468-9 to 1611, and the third, 1611 to date. The period up to 1468-9 The settlement of Orkney and Shetland and the establishment of udal law by Scandinavian settlers was part of the larger population movement of Scandinavian peoples throughout Europe. Earlier writers, including Snorri Sturlason, had interpreted the permanent settlement as a political response to the centralising authority ofHarold Finehair, and in particular to his victory at the battle of Hafrsfjord in 872. This must be modified in light ofrecent research which has redated the battle to some time between the 880s and 9OOs. Moreover recent place-name and archaeological evidence points to settlement by colonists from the west coast ofNorway at an earlier date. -

Appendix C to the Brief to the Court (Protection of Indigenous

SKELETON ARGUMENT OF THE CLAIMANTS APPENDIX C: PROTECTION OF INDIGENOUS CUSTOMARY PROPERTY RIGHTS BY THE COMMON LAW I. The common law has long recognized and protected property rights arising out of pre-existing customary land tenure systems 1. A feature of common law jurisdictions throughout the world is that legally enforceable rights in land may exist on the basis of longstanding use or occupancy.1 In this century alone, Maya people have continuously used and occupied the lands in the areas where their villages are located in southern Belize, for periods far in excess of the ordinarily applicable period for establishing property rights against the Crown or private subjects on the basis of adverse possession.2 2. However, the claimants need not rely on adverse possession in order to establish their property rights. Long before the emergence of the contemporary human rights system at the international level, the British common law included as a central tenet that rights arising out of customary law and usages of a territory that pre-exist the reception of the common law into that territory, continue to be protected and incorporated into the common law.3 As articulated by the Privy Council, the common law has always required … that the rights of property of the inhabitants were to be fully respected. This principle is a usual one under British policy and law when such occupations take place. ... it is not admissible to conclude that the Crown is, generally speaking, entitled to the beneficial ownership of the land as having so passed to the Crown as to displace any presumptive title of the natives.4 3. -

Curing an Improper Tender of Title to Chattels: Past, Present and Commercial Code William D

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Minnesota Law Review 1962 Curing an Improper Tender of Title to Chattels: Past, Present and Commercial Code William D. Hawkland Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Hawkland, William D., "Curing an Improper Tender of Title to Chattels: Past, Present and Commercial Code" (1962). Minnesota Law Review. 2555. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr/2555 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Minnesota Law Review collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 697 Curing an Improper Tender of Title to Chattels: Past, Present and Commercial Code Stolen and encumbered chattels constitute a significant portion of the goods moving in commerce. In order to protect 1the original owners of the goods against the claims of bona fide purchasers, the doctrines of "caveat emptor" and "nemo dat quod non habet" developed in the common law and have been carried into the Uni- form Sales Act. In this Article Professor Hawkland sug- gests that the premises underlying these concepts need to be re-examined and that the concepts themselves should be reformulated to more fairly allocate among original owners, dealers, and purchasers the risks arising when stolen or encumbered goods are sold; one inadvertently dealing in this type of goods needs added protection against "bad faith surprise rejections of title." Profes- sor Hawkland concludes that the Uniform Commercial Code's adoption of the concept of "cure" affords the deal- er a potent weapon against such "bad faith" claims and constitutes a major stride forward toward fairer and more realistic treatment of this problem. -

Black's Law Dictionary®

BLACK'S LAW DICTIONARY® Definitions of the Terms and Phrases of American and English Jurisprudence, Ancient and Modern By HENRY CAMPBELL BLACK, M. A. SIXTH EDITION BY THE PUBLISHER'S EDITORIAL STAFF Coauthors JOSEPH R. NOLAN Associate Justice, Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court and JACQUELINE M. NOLAN-HALEY Associate Clinical Professor, Fordham University School of Law Contributing Authors M. J. CONNOllY Associate Professor (Linguistics), College of Arts & Sciences, Boston College STEPHEN C. HICKS Professor of Law, Suffolk University Law School, Boston, MA MARTINA N. All BRANDI Certified Public Accountant, Bolton, MA ST. PAUL, MINN. WEST PUBLISHING CO. 1990 "BLACK'S LAW DICTIONARY" is a registered trademark of West Publishing Co. Registered in U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. COPYRIGHT @ 1891, 1910, 1933, 1951, 1957, 1968, 1979 WEST PUBLISHING CO. COPYRIGHT @ 1990 By WEST PUBLISHING CO. 50 West Kellogg Boulevard P.O. Box 64526 St. Paul, Mn 55164-0526 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Black, Henry Campbell, 1850-1927. [Law dictionary] Black's law dictionary / by Henry Campbell Black. - 6th ed. / by the publisher's editorial staff; contributing authors, Joseph R. Nolan ... let al.] p. cm. ISBN 0-314-76271-X 1. Law-United States-Dictionaries. 2. Law-Dictionaries. I. Nolan, Joseph R. II. Title. KF156.B53 1990 340' .03-dc20 90-36225 CIP ISBN 0-314-76271-X ISBN 0-314-77165-4 deluxe Black's Law Dictionary 6th Ed. 2nd Reprint-1990 PREFACE This new Sixth Edition starts a second century for Black's Law Dictionary-the standard authority for legal definitions since 1891. -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. 18-1392 IN THE Supreme Court of tfje ®mteb H>tate£ JOHN BARONE Petitioner, v. WELLS FARGO BANK N.A., Respondent. On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit PETITION FOR REHEARING John Barone PO Box 5193 Lighthouse Point, FL 33074 954-644-9900 - Pro Se Petitioner RECEIVED JUL 1 5 2019 OFFICE OF THE CLERK SUPREME COURT lift 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page(s) TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.......................... i PETITION FOR REHEARING..................... 1 REASONS FOR GRANTING REHEARING 1 I. Wells Fargo With Broward Foreclosure Court Assistance Continues Its RICO Schemes and Harassment of Mr. Barone and His Family, Has Unlawfully Set a New Sale Date and Has Failed To Respond To Its Foreclosure Cancellation Notice In Which It Has Updated Credit Reports to Remove Foreclosure 4 II. Fannie Mae and Wells Fargo Treasury Agree ment Substantiates The Government’s Involve ment In Countless Wrongful Foreclosures......6 III. Wells Fargo was NEVER a UCC Article 3 Holder, Failed To Comply With FL Law and De liberately Provided Misleading Information To The District Court 7 CONCLUSION.............................................................. 9 CERTIFICATE OF PRO SE PARTY.......................... 10 APPENDIX Wells Fargo Credit Reporting Notice of Foreclosure Cancelation (Aug. 6th> 2018).................... Appx.l TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Cases Page(s) Bankers Trust (Delaware) v. 236 Beltway Inv., 865 F. Supp. 1186, 1195 (E.D. Va. 1994) 7 Bein v. Heath, 6 How. 228, 247, 12 L.Ed. 416 (1848)... 9 Carpenter v. Longan, 83 U.S. 271 (1872).................. 9 Dept, of Transportation v. Assoc. ofAmer. Railroads, 135 S.