Fee Simple Obsolete Lee Anne Fennell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidance Note

Guidance note The Crown Estate – Escheat All general enquiries regarding escheat should be Burges Salmon LLP represents The Crown Estate in relation addressed in the first instance to property which may be subject to escheat to the Crown by email to escheat.queries@ under common law. This note is a brief explanation of this burges-salmon.com or by complex and arcane aspect of our legal system intended post to Escheats, Burges for the guidance of persons who may be affected by or Salmon LLP, One Glass Wharf, interested in such property. It is not a complete exposition Bristol BS2 0ZX. of the law nor a substitute for legal advice. Basic principles English land law has, since feudal times, vested in the joint tenants upon a trust determine the bankrupt’s interest and been based on a system of tenure. A of land. the trustee’s obligations and liabilities freeholder is not an absolute owner but • Freehold property held subject to a trust. with effect from the date of disclaimer. a“tenant in fee simple” holding, in most The property may then become subject Properties which may be subject to escheat cases, directly from the Sovereign, as lord to escheat. within England, Wales and Northern Ireland paramount of all the land in the realm. fall to be dealt with by Burges Salmon LLP • Disclaimer by liquidator Whenever a “tenancy in fee simple”comes on behalf of The Crown Estate, except for In the case of a company which is being to an end, for whatever reason, the land in properties within the County of Cornwall wound up in England and Wales, the liquidator may, by giving the prescribed question may become subject to escheat or the County Palatine of Lancaster. -

Chapter 6 Summary Ownership of Real Property

Chapter 6 Summary Ownership of Real Property California Real Estate Principles Estate in land - degree of ownership one holds in the land. Feudal system - all land was once owned by the king/government; Allodial System (USA) - although the government detains some rights, individuals own property without proprietary control of government. Freehold estate - the estate lasts at least a lifetime; leasehold estate - renting or leasing. Types of freehold: • Fee Simple (Fee Simple Absolute) - Owns the bundle of rights – unlimited duration; inheritable. • Fee Simple Defeasible is based on an occurrence of a specified event – conditions. • Fee Tail - Property inherited by a monarch is illegal in the United States. • Life Estate: Voluntary Life Estates or "Conventional Life Estates." o Estate in Reversion • A life estate that is deeded to a life tenant - incomplete bundle of rights during lifetime. • A reversion estate that is retained by the grantor. After death of life tenant, grantor has complete bundle of rights. o Estate in remainder: differs from the above because the remainder estate is given to a third party who is known as the remainderman. After death of life tenant, the remainderman has complete bundle of rights. o Pur Autre Vie (estate in reversion/estate in remainder) - life tenant has the incomplete bundle of rights until a third party dies. o Involuntary Life Estates are legal life estates or marital right. It is not possible to sell the property without the consent of the partner, or to own property in one name only. o Dower - a wife's interest in the husband's property; Curtesy - a husband's interest in a wife's property; Homestead - protection against unsecured debts for the party who did not sign for the loan. -

Present Legal Estates in Fee Simple

CHAPTER 3 Present Legal Estates in Fee Simple A. THE ENGLISH LAW T THE beginning of the thirteenth century, when the royal courts of justice were acquiring effective A control of the development of private law, the possible forms of action and their limits were uncertain. It seemed then that a new form of action could be de vised to fit any need which might arise. In the course of that century the courts set themselves to limiting the possible forms of action to a definite list, defining with certainty the scope of permitted actions, and so refusing relief upon states of fact which did not fall within the fixed limits of permitted forms of action. This process, of course, operated to fix and limit the classes of private rights protected by law.101 A parallel process went on with respect to interests in land. At the beginning of the thirteenth century, when alienation of land was becoming possible, it seemed that any sort of interest which ingenuity could devise might be created by apt terms in the transfer creating the interest. Perhaps the form of the gift could create interests of any specified duration, with peculiar rules for descent, with special rights not ordinarily in cident to ownership, or deprived of some of the ordinary incidents of ownership. As in the case of the forms of action, the courts set themselves to limiting the possible interests in land to a definite list, defining with certainty 1o1 Maitland, FoRMS OF ACTION AT CoMMON LAW 51-52 (reprint 1941). 37 38 PERPETUITIES AND OTHER RESTRAINTS the incidents of permitted interests, and refusing to en force provisions of a gift which would add to or subtract from the fixed incidents of the type of interest conveyed. -

The Law of Property

THE LAW OF PROPERTY SUPPLEMENTAL READINGS Class 14 Professor Robert T. Farley, JD/LLM PROPERTY KEYED TO DUKEMINIER/KRIER/ALEXANDER/SCHILL SIXTH EDITION Calvin Massey Professor of Law, University of California, Hastings College of the Law The Emanuel Lo,w Outlines Series /\SPEN PUBLISHERS 76 Ninth Avenue, New York, NY 10011 http://lawschool.aspenpublishers.com 29 CHAPTER 2 FREEHOLD ESTATES ChapterScope ------------------- This chapter examines the freehold estates - the various ways in which people can own land. Here are the most important points in this chapter. ■ The various freehold estates are contemporary adaptations of medieval ideas about land owner ship. Past notions, even when no longer relevant, persist but ought not do so. ■ Estates are rights to present possession of land. An estate in land is a legal construct, something apart fromthe land itself. Estates are abstract, figments of our legal imagination; land is real and tangible. An estate can, and does, travel from person to person, or change its nature or duration, while the landjust sits there, spinning calmly through space. ■ The fee simple absolute is the most important estate. The feesimple absolute is what we normally think of when we think of ownership. A fee simple absolute is capable of enduringforever though, obviously, no single owner of it will last so long. ■ Other estates endure for a lesser time than forever; they are either capable of expiring sooner or will definitely do so. ■ The life estate is a right to possession forthe life of some living person, usually (but not always) the owner of the life estate. It is sure to expire because none of us lives forever. -

VACARIA, a Void Place, Or Waste Ground

[ 323 ] U AND V.. VAGRANTS. VACARIA, A void place, or waste ground. Mem. in Scacc. Mich, 9 Edw. 1 . VACATING RECORDS; See title Record. VACATION, Vacatio.~\ Is all the time between the end of one Term and the beginning of another; and it begins the last day of every Term, as soon as the Court rises. The time from the death of a bishop, or other spiritual person, till the bishopric or dignity is sup plied with another, is also called Vacation. Stats. Westm. 1. c. 21: 14 Edw. 3. st. 4. c. 4. VACATURA, An avoidance of an Ecclesiastical Benefice; as prima Vacatura, the first Avoidance, isfc. VACCARY, Vaccaria. A house or place to keep cows in; a Dairy- house, or Cow-pasture. Fleta, lib. 2. VACCARIUS, The Cow-herd, who looks after the common herd �of cows. Fleta. VADIARE DUELLUM, To wage a combat, where two contend ing parties, on a challenge, give and take a mutual pledge of fighting. Cowell. See title Battel. VADIUM PONERE, To take security, bail or pledges, for the appearance of a defendant in a Court of Justice. Reg. Orig. See Pone. VADIUM MORTUUM; See Mortgage. VADIUM VIVUM, A living Pledge; as when a man borrows a sum of another, and grants him an estate, as of 20/. fier annum, to hold until the rents and profits shall repay the sum borrowed. See Mortgage. VAGABOND, Vagabundus .] One that wanders about, and has no certain dwelling; an idle fellow. See Vagrants. VAGRANTS. Vagrantes.] These are divided into three classes; viz. Bile and Disorderly Persons�Rogues and Vagabonds�and Incorrigible Rogues: And are thus described and particularised at full length in the stat. -

REAL ESTATE LAW LESSON 1 OWNERSHIP RIGHTS (IN PROPERTY) Real Estate Law Outline LESSON 1 Pg

REAL ESTATE LAW LESSON 1 OWNERSHIP RIGHTS (IN PROPERTY) Real Estate Law Outline LESSON 1 Pg Ownership Rights (In Property) 3 Real vs Personal Property 5 . Personal Property 5 . Real Property 6 . Components of Real Property 6 . Subsurface Rights 6 . Air Rights 6 . Improvements 7 . Fixtures 7 The Four Tests of Intention 7 Manner of Attachment 7 Adaptation of the Object 8 Existence of an Agreement 8 Relationships of the Parties 8 Ownership of Plants and Trees 9 Severance 9 Water Rights 9 Appurtenances 10 Interest in Land 11 Estates in Land 11 Allodial System 11 Kinds of Estates 12 Freehold Estates 12 Fee Simple Absolute 12 Defeasible Fee 13 Fee Simple Determinable 13 Fee Simple Subject to Condition Subsequent 14 Fee Simple Subject to Condition Precedent 14 Fee Simple Subject to an Executory Limitation 15 Fee Tail 15 Life Estates 16 Legal Life Estates 17 Homestead Protection 17 Non-Freehold Estates 18 Estates for Years 19 Periodic Estate 19 Estates at Will 19 Estate at Sufferance 19 Common Law and Statutory Law 19 Copyright by Tony Portararo REV. 08-2014 1 REAL ESTATE LAW LESSON 1 OWNERSHIP RIGHTS (IN PROPERTY) Types of Ownership 20 Sole Ownership (An Estate in Severalty) 20 Partnerships 21 General Partnerships 21 Limited Partnerships 21 Joint Ventures 22 Syndications 22 Corporations 22 Concurrent Ownership 23 Tenants in Common 23 Joint Tenancy 24 Tenancy by the Entirety 25 Community Property 26 Trusts 26 Real Estate Investment Trusts 27 Intervivos and Testamentary Trusts 27 Land Trust 27 TEST ONE 29 TEST TWO (ANNOTATED) 39 Copyright by Tony Portararo REV. -

United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

Case: 15-55550, 07/10/2017, ID: 10502017, DktEntry: 127-1, Page 1 of 61 FOR PUBLICATION UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT DAVID CASSIRER; AVA CASSIRER; No. 15-55550 UNITED JEWISH FEDERATION OF SAN 15-55977 DIEGO COUNTY, a California non- profit corporation, D.C. No. Plaintiffs-Appellees, 2:05-cv-03459- JFW-E v. THYSSEN-BORNEMISZA COLLECTION FOUNDATION, an agency or instrumentality of the Kingdom of Spain, Defendant-Appellant. DAVID CASSIRER; AVA CASSIRER; No. 15-55951 UNITED JEWISH FEDERATION OF SAN DIEGO COUNTY, a California non- D.C. No. profit corporation, 2:05-cv-03459- Plaintiffs-Appellants, JFW-E v. OPINION THYSSEN-BORNEMISZA COLLECTION FOUNDATION, an agency or instrumentality of the Kingdom of Spain, Defendant-Appellee. Case: 15-55550, 07/10/2017, ID: 10502017, DktEntry: 127-1, Page 2 of 61 2 CASSIRER V. THYSSEN-BORNEMISZA COLLECTION Appeal from the United States District Court for the Central District of California John F. Walter, District Judge, Presiding Argued and Submitted December 5, 2016 Pasadena, California Filed July 10, 2017 Before: Consuelo M. Callahan, Carlos T. Bea, and Sandra S. Ikuta, Circuit Judges. Opinion by Judge Bea Case: 15-55550, 07/10/2017, ID: 10502017, DktEntry: 127-1, Page 3 of 61 CASSIRER V. THYSSEN-BORNEMISZA COLLECTION 3 SUMMARY* Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act / Holocaust Expropriated Art Recovery Act The panel reversed the district court’s grant of summary judgment, on remand, in favor of Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection Foundation, the defendant in an action under the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act concerning a Camille Pissarro painting that was forcibly taken from the plaintiffs’ great-grandmother by an art dealer who had been appointed by the Nazi government to conduct an appraisal. -

Real Property – Present Estates

Real Property – Present Estates Freehold (owned or possessed outright) or Non-Freehold (possessed through lease) Three types of Freeholds: LEFTS LE – life estate - "O to X for life, and remainder to Y." FT – fee tail - "O to X and the heirs of her body". A fee tail could only pass to the grantee's heirs, which kept the property in the grantee's family. When there is no more living family, the interests revert back to the grantor. Fee tail was abolished in vast majority of states, including New York, and is instead treated as a fee simple in the Grantee). S – fee simple - "To X and X's heirs and assigns" or "To X and X's heirs" or "O to X." Three types of Fee Simple: SAD Subject to a condition precedent ("To X, upon the condition that X passes the bar exam; otherwise, to Y." No title passes to X until X passes) or condition subsequent (BOP: "To X, but if...." "To X on condition that...." "To X provided that....", which creates a right of reentry, not automatic forfeiture). Absolute (no condition). Determinable (conditioned on an uncertain future event, which if it occurs results in automatic forfeiture SUD: "So long as...." "Until it is not used for...." "During the period is used for...."). The law does not favor forfeiture, so the language must be clear, and the possibility of forfeiture will render title unmarketable. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Shelley's Case: To avoid tax to the Grantee, "To Grantee for life, remainder to Grantee's heirs." This delayed payment of transfer tax for the life of the Grantee. -

In Defense of the Fee Simple Katrina M

Notre Dame Law Review Volume 93 | Issue 1 Article 1 11-2017 In Defense of the Fee Simple Katrina M. Wyman New York University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr Part of the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation 93 Notre Dame L. Rev. 1 (2017) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Notre Dame Law Review at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Law Review by an authorized editor of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \\jciprod01\productn\N\NDL\93-1\NDL101.txt unknown Seq: 1 15-NOV-17 13:44 ARTICLES IN DEFENSE OF THE FEE SIMPLE Katrina M. Wyman* Prominent economically oriented legal academics are currently arguing that the fee simple, the dominant form of private landownership in the United States, is an inefficient way for society to allocate land. They maintain that the fee simple blocks transfers of land to higher value uses because it provides property owners with a perpetual monopoly. The critics propose that landown- ership be reformulated to enable private actors to forcibly purchase land from other private own- ers, similar to the way that governments can expropriate land for public uses using eminent domain. While recognizing the significance of the critique, this Article takes issue with it and defends the fee simple. The Article makes two main points in defense of the fee simple. First, addressing the critique on its own economic terms, the Article argues that the critics have not established that there is a robust economic argument for dispensing with the fee simple. -

Patent Transfer and the Bundle of Sticks

GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works Faculty Scholarship 2016 Patent Transfer And The Bundle of Sticks Andrew Michaels The George Washington University Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Michaels, Andrew C., Patent Transfer and the Bundle of Sticks (December 1, 2016). GWU Law School Public Law Research Paper No. 2016-57; GWU Legal Studies Research Paper No. 2016-57. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2883829 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Andrew C. Michaels Patent Transfer DRAFT – Dec. 2016 Patent Transfer And The Bundle of Sticks by Andrew C. Michaels* Abstract In the age of the patent troll, patents are often licensed and transferred. A transferred patent may have been subject to multiple complex license agreements. It cannot be that such a transfer wipes the patent clean of all outstanding license agreements; the licensee must keep the license. But at the same time, it cannot be that the patent transferee becomes a party to a complex and sweeping license agreement – the contract – merely by virtue of acquiring one patent. This article attempts to separate the in personam aspects of a license agreement from its effects on the underlying in rem patent rights, using Hohfeld’s framework of jural relations and the “bundle of sticks” conception of property. -

Priority Rules

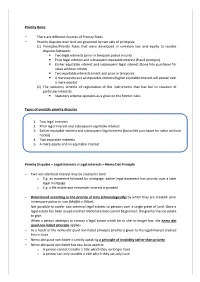

Priority Rules − There are different Sources of Priority Rules − Priority disputes over land are governed by two sets of principles: (1) Principles/Priority Rules that were developed in common law and equity to resolve disputes between: ▪ Two legal interests (prior in tempore potior in iure) ▪ Prior legal interest and subsequent equitable interest (fraud principle) ▪ Earlier equitable interest and subsequent legal interest (bona fide purchaser for value without notice) ▪ Two equitable interests (merit and prior in tempore) ▪ A mere equity and an equitable interest (higher equitable interest will prevail over a mere equity) (2) The statutory scheme of registration of the instruments that has led to creation of particular interests: ▪ Statutory scheme operates as a gloss on the former rules Types of possible priority disputes 1. Two legal interests 2. Prior legal interest and subsequent equitable interest 3. Earlier equitable interest and subsequent legal interest (bona fide purchaser for value without notice) 4. Two equitable interests 5. A mere equity and an equitable interest Priority Disputes – Legal interests v Legal interests – Nemo Dat Principle − Two non-identical interest may be created in land o E.g. an easement followed by mortgage: earlier legal easement has priority over a later legal mortgage o E.g. a life estate and remainder interest is granted − Determined according to the priority of time (chronologically) by which they are created: prior in tempore potior in iure (Moffet v Dillon). − Not possible to confer two identical legal estates to persons over a single piece of land. Once a legal estate has been issued another identical estate cannot be granted: the grantor has no estate to give. -

The Real Estate Law Review

[ Exclusively for: Eddy Leks | 04-Apr-14, 08:41 AM ] ©The Law Reviews The Real Estate Law Review Third Edition Editor David Waterfield Law Business Research The Real Estate Law Review Reproduced with permission from Law Business Research Ltd. This article was first published in The Real Estate Law Review, 3rd edition (published in March 2014 – editor David Waterfield). For further information please email [email protected] The Real Estate Law Review Third Edition Editor David Waterfield Law Business Research Ltd THE LAW REVIEWS THE MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS REVIEW THE RESTRUCTURING REVIEW THE PRIVATE COMPETITION ENFORCEMENT REVIEW THE DISPUTE RESOLUTION REVIEW THE EMPLOYMENT LAW REVIEW THE PUBLIC COMPETITION ENFORCEMENT REVIEW THE BANKING REGULATION REVIEW THE INTERNATIONAL ARBITRATION REVIEW THE MERGER CONTROL REVIEW THE TECHNOLOGY, MEDIA AND TELECOMMUNICATIONS REVIEW THE INWARD INVESTMENT AND INTERNATIONAL TAXATION REVIEW THE CORPORATE GOVERNANCE REVIEW THE CORPORATE IMMIGRATION REVIEW THE INTERNATIONAL INVESTIGATIONS REVIEW THE PROJECTS AND CONSTRUCTION REVIEW THE INTERNATIONAL CAPITAL MARKETS REVIEW THE REAL ESTATE LAW REVIEW THE PRIVATE EQUITY REVIEW THE ENERGY REGULATION AND MARKETS REVIEW THE INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY REVIEW THE ASSET MANAGEMENT REVIEW THE PRIVATE WEALTH AND PRIVATE CLIENT REVIEW THE MINING LAW REVIEW THE EXECUTIVE REMUNERATION REVIEW THE ANTI-BRIBERY AND ANTI-CORRUPTION REVIEW THE CARTELS AND LENIENCY REVIEW THE TAX DISPUTES AND LITIGATION REVIEW THE LIFE SCIENCES LAW REVIEW THE INSURANCE AND REINSURANCE LAW