Patent Transfer and the Bundle of Rights Andrew C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Bundle of Rights

A BUNDLE OF RIGHTS 17 U.S.C. § 106 (2004) Subject to sections 107 through 122, the owner of copyright under this title has the exclusive rights to do and to authorize any of the following: (1) to reproduce the copyrighted work in copies or phonorecords; (2) to prepare derivative works based upon the copyrighted work; (3) to distribute copies or phonorecords of the copyrighted work to the public by sale or other transfer of ownership, or by rental, lease, or lending; (4) in the case of literary, musical, dramatic, and choreographic works, pantomimes, and motion pictures and other audiovisual works, to perform the copyrighted work publicly; (5) in the case of literary, musical, dramatic, and choreographic works, pantomimes, and pictorial, graphic, or sculptural works, including the individual images of a motion picture or other audiovisual work, to display the copyrighted work publicly; and (6) in the case of sound recordings, to perform the copyrighted work publicly by means of a digital audio transmission. __________ A. THE DISTRIBUTION RIGHT 17 U.S.C. § 109 (2004) (a) Notwithstanding the provisions of section 106 (3), the owner of a particular copy or phonorecord lawfully made under this title, or any person authorized by such owner, is entitled, without the authority of the copyright owner, to sell or otherwise dispose of the possession of that copy or phonorecord. Notwithstanding the preceding sentence, copies or phonorecords of works subject to restored copyright under section 104A that are manufactured before the date of restoration -

What Is So Special About Intangible Property? the Case for Intelligent Carryovers Richard A

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Coase-Sandor Working Paper Series in Law and Coase-Sandor Institute for Law and Economics Economics 2010 What Is So Special about Intangible Property? The Case for intelligent Carryovers Richard A. Epstein Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/law_and_economics Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Richard A. Epstein, "What Is So Special about Intangible Property? The asC e for intelligent Carryovers" (John M. Olin Program in Law and Economics Working Paper No. 524, 2010). This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Coase-Sandor Institute for Law and Economics at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Coase-Sandor Working Paper Series in Law and Economics by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHICAGO JOHN M. OLIN LAW & ECONOMICS WORKING PAPER NO. 524 (2D SERIES) What Is So Special about Intangible Property? The Case for Intelligent Carryovers Richard A. Epstein THE LAW SCHOOL THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO August 2010 This paper can be downloaded without charge at: The Chicago Working Paper Series Index: http://www.law.uchicago.edu/Lawecon/index.html and at the Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection. WHAT IS SO SPECIAL ABOUT INTANGIBLE PROPERTY? THE CASE FOR INTELLIGENT CARRYOVERS by Richard A. Epstein* ABSTRACT One of the major controversies in modern intellectual property law is the extent to which property rights conceptions, developed in connection with land or other forms of tangible property, can be carried over to different forms of property, such as rights in the spectrum or in patents and copyrights. -

Leases and the Rule Against Perpetuities

LEASES AND THE RULE AGAINST PERPETUITIES EDWIN H. ABBOT, JUNIOR of the Boston Bar INTRODUCTION The purpose of this article is to consider the application of the rule against perpetuities to leases. A leasehold estate has certain peculiari- ties which distinguish it, as a practical matter, from other estates in land. At common law it required no livery of seisin, and so could be created to begin in futuro. Although it is not an estate of freehold the duration of the estate may be practically unlimited-it may be for 999 years or even in perpetuity. The reversion after an estate for years is necessarily vested, no matter how long the term of the lease may be, yet the leasehold estate is generally terminable at an earlier time upon numerous conditions subsequent, defined in the lease. In other words the leasehold estate determines without condition by the effluxion of the term defined in the lease but such termination may be hastened by the happening of one or more conditions. The application of the rule against perpetuities to such an estate presents special problems. The purpose of this article is to consider the application of the rule to the creation, termination and renewal of leases; and also its effect upon options inserted in leases. II CREATION A leasehold estate may be created to begin in futuro, since livery of seisin was not at common law required for its creation. Unless limited by the rule a contingent lease might be granted to begin a thousand years hence. But the creation of a contingent estate for years to begin a thousand years hence is for practical reasons just as objectionable as the limitation of a contingent fee to begin at such a remote period by means of springing or shifting uses, or by the device of an execu- tory devise. -

Covenants in a Lease Which Run with the Land

COVENANTS IN A LEASE WHICH RUN WITH THE LAND EDwiN H. ADBoT, JR. Assistant Attorney-General, Massachusetts I PRELIMINARY The purpose of this article is to consider anew the tests which deter- mine whether a covenant in a lease will run with the land. The subject is by no means novel. The leading case was decided in 1583,1 if the resolutions promulgated in Spencer's Case can be considered a decision. But in view of the seeming conflict between the first and second reso- 'Spencer's Case (1583, K. B.) 51Co. Rep. 16a. The first two resolutions read as follows: i. When the covenant extends to a thing in esse, parcel of the demise, the thing to be done by force of the covenant is quodammodo annexed and appurtenant to the thing demised, and shall go with the land, and shall bind the assignee although he be not bound by express words: but when the covenant extends to a thing which is not in being at the time of the demise made, it cannot be appurtenant or annexed to the thing which hath no being: as if the lessee covenants to repair the houses demised to him during the term, that is parcel of the contract, and extends to the support of the thing demised, and therefore is quodammodo annexed appurtenant to houses, and shall bind the assignee although he be not bound expressly by the covenant: but in the case at bar, the covenant concerns a thing which was not in esse at the time of the demise made, but to be newly built after, and therefore shall bind the covenantor, his executors or administrators, and not the assignee, for the law will not annex the covenant to a thing which hath no being. -

Standing with a Bundle of Sticks: the All Substantial Rights Doctrine in Action

Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 28 XXVIII Number 3 Article 1 2018 Standing with a Bundle of Sticks: The All Substantial Rights Doctrine in Action Mark J. Abate Goodwin Procter LLP, [email protected] Christopher J. Morten Goodwin Procter LLP, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Mark J. Abate and Christopher J. Morten, Standing with a Bundle of Sticks: The All Substantial Rights Doctrine in Action, 28 Fordham Intell. Prop. Media & Ent. L.J. 477 (2018). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol28/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Standing with a Bundle of Sticks: The All Substantial Rights Doctrine in Action Cover Page Footnote *Mark Abate, a Partner at Goodwin Procter LLP, concentrates his practice on trials and appeals of patent infringement cases, and has particular expertise in matters involving electronics, computers, software, financial systems, and electrical, mechanical, and medical devices. He has tried cases to successful conclusions in U.S. district courts and the U.S. International Trade Commission and has argued appeals before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. He is the former President of both the New York Intellectual Property Law Association and the New Jersey Intellectual Property Law Association, and is a board member of the Federal Circuit Historical Society. -

Chapter 6 Summary Ownership of Real Property

Chapter 6 Summary Ownership of Real Property California Real Estate Principles Estate in land - degree of ownership one holds in the land. Feudal system - all land was once owned by the king/government; Allodial System (USA) - although the government detains some rights, individuals own property without proprietary control of government. Freehold estate - the estate lasts at least a lifetime; leasehold estate - renting or leasing. Types of freehold: • Fee Simple (Fee Simple Absolute) - Owns the bundle of rights – unlimited duration; inheritable. • Fee Simple Defeasible is based on an occurrence of a specified event – conditions. • Fee Tail - Property inherited by a monarch is illegal in the United States. • Life Estate: Voluntary Life Estates or "Conventional Life Estates." o Estate in Reversion • A life estate that is deeded to a life tenant - incomplete bundle of rights during lifetime. • A reversion estate that is retained by the grantor. After death of life tenant, grantor has complete bundle of rights. o Estate in remainder: differs from the above because the remainder estate is given to a third party who is known as the remainderman. After death of life tenant, the remainderman has complete bundle of rights. o Pur Autre Vie (estate in reversion/estate in remainder) - life tenant has the incomplete bundle of rights until a third party dies. o Involuntary Life Estates are legal life estates or marital right. It is not possible to sell the property without the consent of the partner, or to own property in one name only. o Dower - a wife's interest in the husband's property; Curtesy - a husband's interest in a wife's property; Homestead - protection against unsecured debts for the party who did not sign for the loan. -

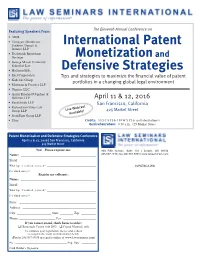

International Patent Monetizationand Defensive Strategies

The Eleventh Annual Conference on Featuring Speakers From: • ARM • Finnegan, Henderson, International Patent Farabow, Garrett & Dunner, LLP • Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer Monetization and • George Mason University School of Law • Hoffman Eitle Defensive Strategies • Intel Corporation Tips and strategies to maximize the financial value of patent • Kudelski Group portfolios in a changing global legal environment • Morrison & Foerster LLP • Pluritas, LLC • Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, LLP April 11 & 12, 2016 • Reed Smith LLP San Francisco, California • Richardson Oliver Law Group LLP Live Webcast 425 Market Street Available! • StoneTurn Group LLP • Uber Credits: 10.5 CA CLE | 10 WA CLE (call about others) Quick when/where: 8:30 a.m., 425 Market Street Patent Monetization and Defensive Strategies Conference April 11 & 12, 2016 | San Francisco, California 425 Market Street Yes! Please register me: 800 Fifth Avenue, Suite 101 | Seattle, WA 98104 Name: ______________________________________________ 206.567.4490 | fax 206.567.5058 | www.lawseminars.com Email: _______________________________________________ What type of credits do you need? ______________________________ 16PATSCA WS For which state(s)? ________________________________________ Register my colleague: Name: ______________________________________________ Email: _______________________________________________ What type of credits do you need? ______________________________ For which state(s)? ________________________________________ Firm: _______________________________________________ -

THE DEFENSIVE PATENT PLAYBOOK James M

THE DEFENSIVE PATENT PLAYBOOK James M. Rice† Billionaire entrepreneur Naveen Jain wrote that “[s]uccess doesn’t necessarily come from breakthrough innovation but from flawless execution. A great strategy alone won’t win a game or a battle; the win comes from basic blocking and tackling.”1 Companies with innovative ideas must execute patent strategies effectively to navigate the current patent landscape. But in order to develop a defensive strategy, practitioners must appreciate the development of the defensive patent playbook. Article 1, Section 8, Clause 8 of the U.S. Constitution grants Congress the power to “promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.”2 Congress attempts to promote technological progress by granting patent rights to inventors. Under the utilitarian theory of patent law, patent rights create economic incentives for inventors by providing exclusivity in exchange for public disclosure of technology.3 The exclusive right to make, use, import, and sell a technology incentivizes innovation by enabling inventors to recoup the costs of development and secure profits in the market.4 Despite the conventional theory, in the 1980s and early 1990s, numerous technology companies viewed patents as unnecessary and chose not to file for patents.5 In 1990, Microsoft had seven utility patents.6 Cisco © 2015 James M. Rice. † J.D. Candidate, 2016, University of California, Berkeley, School of Law. 1. Naveen Jain, 10 Secrets of Becoming a Successful Entrepreneur, INC. (Aug. 13, 2012), http://www.inc.com/naveen-jain/10-secrets-of-becoming-a-successful- entrepreneur.html. -

Inverse Condemnation and Compensatory Relief for Temporary Regulatory Takings: First English Evangelical Lutheran Church V

Nebraska Law Review Volume 67 | Issue 2 Article 8 1988 Inverse Condemnation and Compensatory Relief for Temporary Regulatory Takings: First English Evangelical Lutheran Church v. Los Angeles County, 107 S. Ct. 2378 (1987) Joseph C. Vitek University of Nebraska College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr Recommended Citation Joseph C. Vitek, Inverse Condemnation and Compensatory Relief for Temporary Regulatory Takings: First English Evangelical Lutheran Church v. Los Angeles County, 107 S. Ct. 2378 (1987), 67 Neb. L. Rev. (1988) Available at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr/vol67/iss2/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Note Inverse Condemnation and Compensatory Relief for Temporary Regulatory Takings FirstEnglish Evangelical Lutheran Church v. Los Angeles County, 107 S. Ct. 2378 (1987) TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction ............................................... 435 II. Background Cases ......................................... 437 III. Facts of FirstEnglish Church ............................. 439 IV. Analysis ................................................... 441 A. Ripeness for Review .................................. 441 B. The Just Compensation Requirement ................. 444 1. Physical Occupation, Regulatory, and Temporary -

A General Overview of the Treatment of Intellectual Property Licenses in Bankruptcy by Bruce Buechler, Esq

A General Overview of the Treatment of Intellectual Property Licenses in Bankruptcy By Bruce Buechler, Esq. Lowenstein Sandler LLP Editor's Note: The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not reflect those of Lowenstein Sandler LLP or any of its clients. n a bankruptcy case, a debtor has the ability to assume In addition, section 365(c) of the Bankruptcy Code provides I(i.e., affirm) or reject (i.e., disavow) executory contracts that when applicable non-bankruptcy law prohibits a and unexpired leases. A debtor’s ability to assume or reject contract’s assignment, it may not be assumed or assigned by an executory contract or unexpired lease is recognized as a debtor without the permission of the non-debtor counter- one of the primary purposes and essential tools available to party to the contract. Thus, in connection with licenses of a debtor under the Bankruptcy Code. The Bankruptcy Code intellectual property, section 365 is fraught with difficulties. allows a debtor to keep in place favorable contracts, and Intellectual property contracts can consist of, among other discard and relieve it of burdensome contracts, and thus things, technology licenses, patents, copyrights, trademarks avoid future performance obligations under such contracts. and/or trade secrets. If the debtor assumes a contract, it can compel the non- debtor contract party to continue to perform. Likewise, a In determining whether an intellectual property agreement is debtor has the ability to assume and assign (i.e., sell) the an “executory contract” within the meaning of section 365(c) contract to a third party, notwithstanding most provisions and, therefore, potentially subject to assumption, many in a contract or lease, that would prohibit or restrict the courts make a distinction as to whether the agreement is an assignment of such lease or contract. -

Uniform Environmental Covenants Act

UNIFORM ENVIRONMENTAL COVENANTS ACT drafted by the NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF COMMISSIONERS ON UNIFORM STATE LAWS and by it APPROVED AND RECOMMENDED FOR ENACTMENT IN ALL THE STATES at its MEETING IN ITS ONE-HUNDRED-AND-TWELFTH YEAR WASHINGTON, DC AUGUST 1-7, 2003 WITH PREFATORY NOTE AND COMMENTS Copyright ©2003 By NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF COMMISSIONERS ON UNIFORM STATE LAWS September 27, 2018 DRAFTING COMMITTEE ON UNIFORM ENVIRONMENTAL COVENANTS ACT WILLIAM R. BREETZ, JR., University of Connecticut School of Law, Connecticut Urban Legal Initiative, 35 Elizabeth Street, Room K-202, Hartford, CT 06105, Chair MARION W. BENFIELD, JR., 10 Overlook Circle, New Braunfels, TX 78132 DAVID D. BIKLEN, 153 N. Beacon St., Hartford, CT 06105 STEPHEN C. CAWOOD, 108 ½ Kentucky Ave., P.O. Drawer 128, Pineville, KY 40977-0128 BRUCE A. COGGESHALL, One Monument Sq., Portland, ME 04101 FRANK W. DAYKIN, 2180 Thomas Jefferson Dr., Reno, NV 89509, Committee on Style Liaison THEODORE C. KRAMER, 45 Walnut St., Brattleboro, VT 05301 DONALD E. MIELKE, Ken Caryl Starr Centre, 7472 S. Shaffer Ln., Suite 100, Littleton, CO 80127 LARRY L. RUTH, 530 S. 13th St., Suite 110, Lincoln, NE 68508-2820, Enactment Plan Coordinator HIROSHI SAKAI, 3773 Diamond Head Circle, Honolulu, HI 96815 YVONNE L. THARPES, Legislature of the Virgin Islands, Capitol Building, P.O. Box 1690, St. Thomas, VI 00804 MICHELE L. TIMMONS, Office of the Revisor of Statutes, 700 State Office Bldg., 100 Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd., St. Paul, MN 55155 KURT A. STRASSER, University of Connecticut School of Law, 65 Elizabeth St., Hartford, CT 06105-2290, Reporter EX OFFICIO K. -

Covenant Marriage: Legislating Family Values

COVENANT MARRIAGE: LEGISLATING FAMILY VALUES A MY L. STEWART* INTRODUCTION Hardly a social problem exists that has not been attributed to the breakdown of the American family, and hardly has there been a time in American history when this has not been true. Today, a decline in “family values” is blamed for crime, drug use, low educational achievement, poverty, and probably in some circles, for the weather. The solution to these problems, the theory goes, is to save the family, and the way to save the family is to make it harder to get divorced. In some states, conservative lawmakers are charging to the rescue. They propose a concept called “covenant marriage,” a sort of “marriage deluxe” that would be slightly harder to enter and much harder to exit than a “regular” marriage. Their goal is to reduce the divorce rate by preventing bad marriages before they begin and by restricting divorce once a couple is married. In July 1997, Louisiana became the first state to pass a covenant marriage bill.1 This Note assesses the likely effectiveness of such a measure. It concludes that marriages are better made in the human heart than in the statehouse halls. Part I of this Note reviews the evolution of American divorce law to provide an historical context for the current movement to reform those laws. As one product of this new reform movement, the covenant marriage proposal itself is described in detail. In an effort to evaluate whether new restrictions on divorce will improve social conditions, the current, less restrictive scheme of no-fault divorce is analyzed to determine whether it has been responsible for adverse social consequences.