Towards an Understanding of the Nature and Impacts of the Nobel Peace Prize

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded from the ACCORD As the “Saviours”, and Darfurians Negatively As Only Just the “Survivors”

CONTENTS EDITORIAL 2 by Vasu Gounden FEATURES 3 Paramilitary Groups and National Security: A Comparison Between Colombia and Sudan by Jerónimo Delgådo Caicedo 13 The Path to Economic and Political Emancipation in Sri Lanka by Muttukrishna Sarvananthan 23 Symbiosis of Peace and Development in Kashmir: An Imperative for Conflict Transformation by Debidatta Aurobinda Mahapatra 31 Conflict Induced Displacement: The Pandits of Kashmir by Seema Shekhawat 38 United Nations Presence in Haiti: Challenges of a Multidimensional Peacekeeping Mission by Eduarda Hamann 46 Resurgent Gorkhaland: Ethnic Identity and Autonomy by Anupma Kaushik BOOK 55 Saviours and Survivors: Darfur, Politics and the REVIEW War on Terror by Karanja Mbugua This special issue of Conflict Trends has sought to provide a platform for perspectives from the developing South. The idea emanates from ACCORD's mission to promote dialogue for the purpose of resolving conflicts and building peace. By introducing a few new contributors from Asia and Latin America, the editorial team endeavoured to foster a wider conversation on the way that conflict is evolving globally and to encourage dialogue among practitioners and academics beyond Africa. The contributions featured in this issue record unique, as well as common experiences, in conflict and conflict resolution. Finally, ACCORD would like to acknowledge the University of Uppsala's Department of Peace and Conflict Research (DPCR). Some of the contributors to this special issue are former participants in the department's Top-Level Seminars on Peace and Security, a Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) advanced international training programme. conflict trends I 1 EDITORIAL BY VASU GOUNDEN In the autumn of November 1989, a German continually construct walls in the name of security; colleague in Washington DC invited several of us walls that further divide us from each other so that we to an impromptu celebration to mark the collapse have even less opportunity to know, understand and of Germany’s Berlin Wall. -

Newsletter Koff

Kompetenzzentrum Friedensförderung Centre pour la promotion de la paix Centro per la promozione della pace Center for Peacebuilding NEWSLETTER KOFF 1 September 2005 / Nr. 40 From the Center for Peacebuilding / swisspeace South-Eastern Europe Roundtable on internally displaced persons in the former Yugoslavia Do no Harm training workshop Event on transformation of land conflicts KOFF evaluation report now out KOFF member organizations now 40 nd 2 edition KOFF report on „dealing with the past“ „From Reaction to Prevention“: GPPAC Conference at United Nations headquarters in New York ACSF electoral training project in Afghanistan Focus Striving for improved cooperation between UN and civil society News from Swiss NGOs „Peace perspectives 1945–1989–2100“: Peace Council seminar in Trogen „Play for Peace“ - intercultural youth camps at Pestalozzi Children’s Village HEKS: Emergency aid, repatriation projects and conflict prevention in Southern Sudan The two new KOFF member organizations: „mission 21“and „Society for Threatened Peoples“ News from Swiss Government Agencies Switzerland part of Aceh monitoring mission Swiss federalism: a model for Bosnia Herzegovina? New COPRET head Publisher: Center for International Partner Organizations Peacebuilding KOFF Sonnenbergstrasse 17 Conciliation Resources, ECCP, EPLO, FriEnt, SPICE CH - 3000 Bern 7 Tel: +41 (0)31 330 12 12 www.swisspeace.org/koff Events, Publications, Web tip KOFF-Newsletter Nr. 40 2 From the Center for Peacebuilding / swisspeace Links South-Eastern Europe Roundtable on internally displaced persons in the former Yugoslavia Documents : Walter Kälin, Representative of the UN Secretary-General on the Human Rights of Internally Displaced Persons, was guest speaker at the KOFF South-Eastern Europe Guiding Principles on Roundtable on August 22. -

Wahu Kaara of Kenya

THE STRENGTH OF MOTHERS: The Life and Work of Wahu Kaara of Kenya By Alison Morse, Peace Writer Edited by Kaitlin Barker Davis 2011 Women PeaceMakers Program Made possible by the Fred J. Hansen Foundation *This material is copyrighted by the Joan B. Kroc Institute for Peace & Justice. For permission to cite, contact [email protected], with “Women PeaceMakers – Narrative Permissions” in the subject line. THE STRENGTH OF MOTHERS WAHU – KENYA TABLE OF CONTENTS I. A Note to the Reader ……………………………………………………….. 3 II. About the Women PeaceMakers Program ………………………………… 3 III. Biography of a Woman PeaceMaker – Wahu Kaara ….…………………… 4 IV. Conflict History – Kenya …………………………………………………… 5 V. Map – Kenya …………………………………………………………………. 10 VI. Integrated Timeline – Political Developments and Personal History ……….. 11 VII. Narrative Stories of the Life and Work of Wahu Kaara a. The Path………………………………………………………………….. 18 b. Squatters …………………………………………………………………. 20 c. The Dignity of the Family ………………………………………………... 23 d. Namesake ………………………………………………………………… 25 e. Political Awakening……………………………………………..………… 27 f. Exile ……………………………………………………………………… 32 g. The Transfer ……………………………………………………………… 39 h. Freedom Corner ………………………………………………………….. 49 i. Reaffirmation …………………….………………………………………. 56 j. A New Network………………….………………………………………. 61 k. The People, Leading ……………….…………………………………….. 68 VIII. A Conversation with Wahu Kaara ….……………………………………… 74 IX. Best Practices in Peacebuilding …………………………………………... 81 X. Further Reading – Kenya ………………………………………………….. 87 XI. Biography of a Peace Writer -

General Assembly Official Records Sixtieth Session

United Nations A/60/PV.41 General Assembly Official Records Sixtieth session 41st plenary meeting Monday, 31 October 2005, 3 p.m. New York President: Mr. Eliasson ............................................ (Sweden) The meeting was called to order at 2.40 p.m. technology and the complications that can arise from the peaceful use of nuclear energy. While the IAEA Agenda item 84 (continued) protects the right to use nuclear energy for peaceful purposes, it must also ensure that such a right is Report of the International Atomic Energy Agency exercised in compliance with States’ non-proliferation obligations under article II of the NPT and the full Note by the Secretary-General (A/60/204) implementation of IAEA safeguards, and with the utmost transparency. Draft resolution (A/60/L.13) The IAEA has a central role in combating nuclear Mr. Ng (Singapore): My delegation would like to proliferation. It is therefore vital that its safeguards congratulate the Director General of the International regime remains capable of responding to new Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), Mr. Mohamed challenges within its mandate. In this context, ElBaradei, and the IAEA itself on being jointly Singapore supports the several key initiatives taken awarded this year’s Nobel Peace Prize. This award is recently by the IAEA Board of Governors. They both well deserved and timely. It reflects the important include the creation of an advisory committee of the role the IAEA plays in nuclear non-proliferation. Board on safeguards and verification, establishing the Additional Protocol as the new standard for safeguards With the increasing challenges posed by nuclear verification, and ushering in a modified version of the proliferation, coupled with the rise of nuclear power as Small Quantities Protocol. -

Year in Review 2008

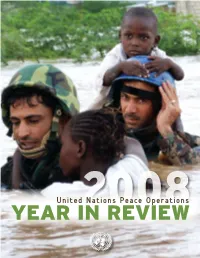

United Nations Peace Operations YEAR IN2008 REVIEW asdf TABLE OF CONTENTS 12 ] UNMIS helps keep North-South Sudan peace on track 13 ] MINURCAT trains police in Chad, prepares to expand 15 ] After gaining ground in Liberia, UN blue helmets start to downsize 16 ] Progress in Côte d’Ivoire 18 ] UN Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea is withdrawn 19 ] UNMIN assists Nepal in transition to peace and democracy 20 ] Amid increasing insecurity, humanitarian and political work continues in Somalia 21 ] After nearly a decade in Kosovo, UNMIK reconfigures 23 ] Afghanistan – Room for hope despite challenges 27 ] New SRSG pursues robust UN mandate in electoral assistance, reconstruction and political dialogue in Iraq 29 ] UNIFIL provides a window of opportunity for peace in southern Lebanon 30 ] A watershed year for Timor-Leste 33 ] UN continues political and peacekeeping efforts in the Middle East 35 ] Renewed hope for a solution in Cyprus 37 ] UNOMIG carries out mandate in complex environment 38 ] DFS: Supporting peace operations Children of Tongo, Massi, North Kivu, DRC. 28 March 2008. UN Photo by Marie Frechon. Children of Tongo, 40 ] Demand grows for UN Police 41 ] National staff make huge contributions to UN peace 1 ] 2008: United Nations peacekeeping operations observes 60 years of operations 44 ] Ahtisaari brings pride to UN peace efforts with 2008 Nobel Prize 6 ] As peace in Congo remains elusive, 45 ] Security Council addresses sexual violence as Security Council strengthens threat to international peace and security MONUC’s hand [ Peace operations facts and figures ] 9 ] Challenges confront new peace- 47 ] Peacekeeping contributors keeping mission in Darfur 48 ] United Nations peacekeeping operations 25 ] Peacekeepers lead response to 50 ] United Nations political and peacebuilding missions disasters in Haiti 52 ] Top 10 troop contributors Cover photo: Jordanian peacekeepers rescue children 52 ] Surge in uniformed UN peacekeeping personnel from a flooded orphanage north of Port-au-Prince from1991-2008 after the passing of Hurricane Ike. -

Announcements February 28, 2020

Announcements February 28, 2020 Barack Hussein Obama II (/bəˈrɑːk huːˈseɪn oʊˈbɑːmə/ (About this soundlisten);[1] born August 4, 1961) is an American attorney and politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, he was the first African-American president of the United States. He previously served as a U.S. senator from Illinois from 2005 to 2008 and an Illinois state senator from 1997 to 2004. Obama was born in Honolulu, Hawaii. After graduating from Columbia University in 1983, he worked as a community organizer in Chicago. In 1988, he enrolled in Harvard Law School, where he was the first black person to head the Harvard Law Review. After graduating, he became a civil rights attorney and an academic, teaching constitutional law at the University of Chicago Law School from 1992 to 2004. Turning to elective politics, he represented the 13th district from 1997 until 2004 in the Illinois Senate, when he ran for the U.S. Senate. Obama received national attention in 2004 with his March Senate-primary win, his well-received July Democratic National Convention keynote address, and his landslide November election to the Senate. In 2008, he was nominated for president a year after his presidential campaign began, and after close primary campaigns against Hillary Clinton. Obama was elected over Republican John McCain and was inaugurated on January 20, 2009. Nine months later, he was named the 2009 Nobel Peace Prize laureate. • Obama signed many landmark bills into law during his first two years in office. -

The Nobel Peace Prize

TITLE: Learning From Peace Makers OVERVIEW: Students examine The Dalai Lama as a Nobel Laureate and compare / contrast his contributions to the world with the contributions of other Nobel Laureates. SUBJECT AREA / GRADE LEVEL: Civics and Government 7 / 12 STATE CONTENT STANDARDS / BENCHMARKS: -Identify, research, and clarify an event, issue, problem or phenomenon of significance to society. -Gather, use, and evaluate researched information to support analysis and conclusions. OBJECTIVES: The student will demonstrate the ability to... -know and understand The Dalai Lama as an advocate for peace. -research and report the contributions of others who are recognized as advocates for peace, such as those attending the Peace Conference in Portland: Aldolfo Perez Esquivel, Robert Musil, William Schulz, Betty Williams, and Helen Caldicott. -compare and contrast the contributions of several Nobel Laureates with The Dalai Lama. MATERIALS: -Copies of biographical statements of The Dalai Lama. -List of Nobel Peace Prize winners. -Copy of The Dalai Lama's acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize. -Bulletin board for display. PRESENTATION STEPS: 1) Students read one of the brief biographies of The Dalai Lama, including his Five Point Plan for Peace in Tibet, and his acceptance speech for receiving the Nobel Prize for Peace. 2) Follow with a class discussion regarding the biography and / or the text of the acceptance speech. 3) Distribute and examine the list of Nobel Peace Prize winners. 4) Individually, or in cooperative groups, select one of the Nobel Laureates (give special consideration to those coming to the Portland Peace Conference). Research and prepare to report to the class who the person was and why he / she / they won the Nobel Prize. -

A Day in the Future Accelerating Solutions to Security Threats

A Day In The Future Accelerating Solutions to Security Threats Leland Russell and Greg Austin FEBRUARY 2008 ACKNOWLEDGMENT The EastWest Institute would like to acknowledge the generous support of the Francis Finlay Foundation for financial support to its work on framing new approaches to global security. We live in a world of new and evolving threats, threats that could not have been anticipated when the UN was founded in 1945 – threats like nuclear terrorism, and State collapse from the witch’s brew of poverty, disease and civil war. Report of the UN Secretary General's High-Level Panel on Threats, Challenges and Change, December 2004 1 THE THREATS WE FACE The security environment of the future will be shaped by transnational threats evolving from wars, violent extremism, natural disasters, pandemics, and unaddressed systemic problems—including poverty, organized crime, and environmental degradation. Technology will remain a force-multiplier for violent extremists, not only for higher levels of lethality, but for propaganda dissemination. Real-time, global communication will exacerbate the psychological impact of potential threats and the aftermath of incidents. The confluence of these circumstances will cause rising international anxiety and insecurity about physical well-being, prosperity, and even the sustainability of human existence. This will in turn feed an intensifying backlash against “modernity” and the pace of social and technological change, based on fears—both real and imagined. In this environment, the preservation of our common security—whether military, economic, social, or environmental—is becoming increasingly more difficult and complex. Consider, for example, the potential security implications of the energy challenge resulting from the projected one-third increase in the global population over the next 40 years, as portrayed by the CEO of Royal Dutch Shell plc, Jeroen van der Veer: Energy use in 2050 may be twice as high as it is today or higher still. -

Friedensnobelpreisträger Alljährlich Am 10

WikiPress Friedensnobelpreisträger Alljährlich am 10. Dezember, dem Todestag Alfred Nobels, wird der Frie- Friedensnobelpreisträger densnobelpreis vom norwegischen König in Oslo verliehen. Im Jahr 1901 erhielt Henri Dunant für die Gründung des Roten Kreuzes und seine Ini- Geschichte, Personen, Organisationen tiative zum Abschluss der Genfer Konvention als Erster die begehrte Aus- zeichnung. Mit dem Preis, den Nobel in seinem Testament gestiftet hatte, wurden weltweit zum ersten Mal die Leistungen der Friedensbewegung Aus der freien Enzyklopädie Wikipedia offiziell gewürdigt. Im Gegensatz zu den anderen Nobelpreisen kann der zusammengestellt von Friedensnobelpreis auch an Organisationen vergeben werden, die an ei- nem Friedensprozess beteiligt sind. Dieses Buch stellt in ausführlichen Achim Raschka Beiträgen sämtliche Friedensnobelpreisträger seit 1901 sachkundig vor. Alle Artikel sind aus der freien Enzyklopädie Wikipedia zusammen- gestellt und zeichnen ein lebendiges Bild von der Vielfalt, Dynamik und Qualität freien Wissens – zu dem jeder beitragen kann. Achim Raschka hat einige Jahre seines Lebens damit verbracht, Biologie zu studieren, und vor vier Jahren sein Diplom mit den Schwerpunkten Zoologie, Humanbiologie, Ökologie und Paläontologie abgeschlossen. Er ist verheiratet und Vater von zwei Kindern, hat einen Facharbeiterbrief als Physiklaborant, ist ehemaliger Zivildienstleistender einer Jugendherberge in Nordhessen sowie ambitionierter Rollenspieler und Heavy-Metal-Fan. Während seines Studiums betreute er verschiedene Kurse, vor allem in Ökologie (Bodenzoologie und Limnologie), Zoologie sowie in Evolutions- biologie und Systematik. Seit dem Studium darf er als Dozent an der Frei- en Universität in Berlin regelmäßig eigene Kurse in Ökologie geben. Au- ßerdem war er kurz beim Deutschen Humangenomprojekt (DHGP) und betreute mehrere Jahre Portale bei verschiedenen Internetplattformen. Zur Wikipedia kam Achim Raschka während seiner Zeit im Erziehungs- urlaub für seinen jüngeren Sohn. -

Literaturverzeichnis

Literaturverzeichnis Die Literaturliste folgt der deutschen Alphabetisierung, d.h.: aa und a, werden an den Beginn und nicht an das Ende des Alphabetes gestellt, die Umlaute ce und 0 als ä und ö behandelt. Examensarbeiten, hovedoppgaver, die nicht über den Buchhandel erhältlich sind, sondern nur in Universitäts- und Institutsbibliotheken bzw. dem Archiv der Arbeiterbewegung eingesehen werden können, sind mit * gekennzeichnet, während die publizierten Ex amensarbeiten mit -+ versehen sind. -+ Knut Aagesen, Fagopposisjonen av 1940 [Die Gewerkschaftsopposition von 1940], in: 1940 - Fra n0ytral ti1 okkupert [1940 - von neutral bis okkupiert], Oslo 1969 * 0yvind Aasmul, Bruddet i Bergens arbeiderparti i 1923 [Die Spaltung in der Arbeiterpartei in Bergen 1923], Universität Bergen 1977 * Ame Alnces, So1kjerringer og fiskbcerere. Om arbeideme pä klippfiskbcergan i Kristiansund pä 1930-tallet [Sonnenweiber und Fischträger. Über die Arbeiter auf den Trockenfisch klippen in Kristiansund in den 1930er Jahren], Universität Trondheim 1982 Hans Amundsen, Christofer Homsrud, Oslo 1939 Ders., Trygve Lie - gutten fra Grorud som ble generalsekretcer i FN [Trygve Lie-der Junge aus Grorud, der UNO-Generalsekretär wurde], Oslo 1946 * Trond Amundsen, Fiskerkommunismen i nord: Vilkarene for kommunistenes oppslutning pä kysten av 0st-Finnmark i perioden 1930-1940 [Fischereikommunismus im Norden: Bedingungen für die Zustimmung für die Kommunisten in den Küstengebieten von Ost-Finnmark in der Periode 1930-1940], Universität Troms0 1991 Haakon With Andersen, Kapitalisme med menneskelig ansikt ? Fra akkord ti1 fast 10nn ved Akers Mek. Verksted i 1957 [Kapitalismus mit menschlichem Gesicht ? Von Akkord zu festem Gehalt in Akers Mechanischen Werkstätten im Jahre 1957], in: Tidsskrift for arbeiderbevegelsens historie, 2 ( 1981) Roy Andersen, Sin egen fiende. Et portrett av Asbj0rn Bryhn [Sein eigener Feind. -

![Internasjonal Politikk [2·07]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5813/internasjonal-politikk-2%C2%B707-395813.webp)

Internasjonal Politikk [2·07]

[2·07] politikk Internasjonal Forord: Internasjonal politikk 70 år [2·07] Internasjonal Birgitte Kjos Fonn Internasjonal Politikk i Norge. En disiplins fremvekst politikk i første halvdel av 1900-tallet Halvard Leira & Iver B. Neumann Internasjonal politikk og Forsvaret. Internasjonalisering IP-fagets norske historie og akademisering av den militære utdanningen Nina Græger IP i forsvarsutdanningen Tekst og kontekst. John Sanness om Vietnam og Afghanistan Oddbjørn Melle Tekst og tolkning hos John Sanness Da Diez de Abril kom til verden – og menneske- rettighetene kom til Diez de Abril Nye nettverk, ny internasjonal politikk Roy Krøvel Aktuelt: «Sakkyndig og objektiv oplysning – og skrevet i Internasjonal politikk 70 år en populær form» – Internasjonal politikk 70 år Birgitte Kjos Fonn Debatt: Helhetsperspektiver på norsk utenrikspolitikk Sverre Lodgaard Norske selvbilder – norsk utenrikspolitikk Halvard Leira Selvbilder med begrensninger Morten Aasland Bokspalte Nr. 2 - 2007 65. Årgang Summaries Norwegian Institute Norsk of International Utenrikspolitisk ISSN 0020-577X Affairs Institutt Internasjonal politikk [retningslinjer for manus] Artiklene bør ikke overskride 25 sider A 4, dobbel linjeavstand, eller 45 000 tegn inkludert mellomrom. Internasjonal politikk tar ikke inn bidrag som samtidig publiseres i andre Norden- baserte publikasjoner. Kun manus på norsk, dansk eller svensk mottas. Endelige bidrag leveres formatert for PC. Oppgi system og nødvendige spesifikasjoner. I. Anbefalt format for Til kildehenvisninger brukes forfatternavn -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized ...z w ~ ~ ~ w C ..... Z w ~ oQ. -'w >w Public Disclosure Authorized C -' -ct ou V') Public Disclosure Authorized " Public Disclosure Authorized VIOLENCE PREVENTION A Critical Dimension of Development Background 2 Agenda 4 Participant Biographies 10 Photo Contest Imagining Peace 32 Photo Contest Winners 33 Photo Contest Finalists 36 Conference Organizing Team & Contact Information 43 The Conflict, Crime and Violence team in the Social high levels of violent crime, street violence, do Development Department (SDV) has organized a mestic violence, and other kinds of violence. day and a half event focusing on "Violence Pre vention: A Critical Dimension of Development". Violence takes many forms: from the traditional As the issue of violence crosscuts other agendas protection racket by illegal organizations to the of the World Bank, the objectives of the event are rise of international illegal trafficking (arms, hu to raise World Bank staff's awareness of the link mans, drugs), from gang-based urban violence between violence prevention and development, its and crime to politically-motivated violence fueled relevance for development, and to present the ra by socio-economic grievances. All these forms of tionale for increased attention to violence preven violence concur to erode the well-being of all- and tion and reduction within World Bank operations. more acutely of the poorest - and to stymie devel opment efforts. Social failure, weak institutional Violence has become one of the most salient de capacity and the lack of a legal framework to pro velopmental issues in the global agenda. Its nega tect and guarantee people's safety and rights cre tive impact on social and economic development ate a climate of lawlessness and engender dynam in countries across the world has been well doc ics of state-within-state behavior by increasingly umented.