From Rangoon College to University of Yangon – 1876 to 1920

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

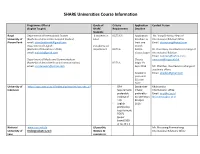

SHARE Universities Course Information

SHARE Universities Course Information Programme Offered Quota of Criteria Application Contact Person (English Taught) SHARE Requirement Deadline Students Royal Department of International Studies 6 students in IELTS 6.5 Application Mr. Vong Chhorvy, Head of University of (Bachelor of Arts in International Studies) total deadline: at International Relation Office Phnom Penh email: [email protected] least one Email: [email protected] Department of English 2 students per month (Bachelor of Education in TEFL) department IELTS 6 before Dr. Oum Ravy, Vice Rector in charge of email: [email protected] classes begin International Relation Email: [email protected], Department of Media and Communication Classes [email protected] (Bachelor of Art in Media and Communication) IELTS 6 begin 19 email: [email protected] Sept 2016 Mr. Phal Des, Vice Rector in charge of academic affairs Academic Email: [email protected] year ends 30 June 2017 University of http://apps.acts.ui.ac.id/index.php/courses/courses_all - GPA September Khairunnisa Indonesia requirement: Intake: International Office preferably preferably Email: [email protected] 3.0 (out of no later than [email protected] 4.0) 30 April - English 2016 proficiency requirement: TOEFL (paper based) 500 or IELTS 5.5 National www.nuol.edu.la (if possible, Mr. Phouvong Phimmakong University of Undergraduate Level: NUOL is to International Relations Office Laos consider to NUOL is under process to develop and launch host in- Email: [email protected] programs-taught in English. Now, there are five coming phoovongphim@gmailcom international programs being considered by the students for University Ministry of Education and Sports. -

University of Yangon History & Location of the University

CHINLONE Connecting Higher Education Institutions for a New Leadership on National Education Erasmus+ KA2 University of Yangon History & Location of the University ° Established on 1st Dec, 1920 ° The first national university in Myanmar ° Yangon, the commercial and former capital city of Myanmar with two campus – Main Campus and Hlaing Campus on Pyay Road Academic Departments 21 Academic Departments headed by a Professor offered undergraduate and postgraduate level courses 13 Arts Departments: Myanmar, English, History, Law, Philosophy, Psychology, Anthropology, Archaeology, International Relations, Political Science, Geography, Oriental Studies and Library & Information Studies 8 Science Departments : Physics, Chemistry, Mathematics, Zoology, Botany, Industrial Chemistry, Geology and Computer Studies Degrees Offered University of Yangon is now an institution for undergraduate & postgraduate studies offering the following degrees: BA& BSc (Dec, 2013) Postgraduate Diploma BA (Hons), BSc (Hons) MA, MSc MRes PhD Faculty Members & Admin Staff Rector 1 Pro-Rector 3 Faculty Staff Professor 47 Associate Professor 45 Lecturer 361 Assistant Lecturer 239 Tutor/Demonstrator 142 Total (Faculty Staff) 834 Total (Admin. Staff ) 546 Total 1383 Administrative Structure of the University of Yangon Rector of the University Dr. Pho Kaung, Ph D Physics, Hokkaido University , Japan Principal Responsibility - taking charge of the all academic and administration of the university Pro-Rectors Dr. Omar Kyaw (LL.D Marine Environmental Law, Hiroshima University, -

O Verseas Partner U Niversities

Overseas Partner Universities [Inter-University Agreements] [Inter-Departmental Agreements] (60 universities in 30 countries/regions) As of 2019 June 1 (28 Faculties, etc. in 16 countries/regions) As of 2019 June 1 Country/Region University Affiliate Since Akita University Department Country/Region University/Department Affiliate Since Indian Institute of Technology Madras 2014 March 2 India VIT University 2015 June 12 Faculty of Engineering, Hasanuddin University 2014 April 23 Technology, Institut Teknologi Bandung 2012 July 12 Indonesia Trisakti University 2014 June 10 Asia Faculty of Geological Engineering, Universitas Padjadjaran 2018 October 1 Indonesia Gadjah Mada University 2015 June 8 Universitas Pertamina 2018 August 16 Graduate Faculty of Science, Thailand Kasetsart University 2019 May 29 Padjadjaran University 2019 March 26 School of International Hanbat National University 2001 June 8 Red Sea University Faculty Resource Middle Sudan of Earth Sciences and 2016 December 10 South Korea Wonkwang University 2007 October 12 Sciences East Faculty of Marine Sciences Kangwon National University 2008 March 24 Technical Faculty in Bor, 2016 May 3 Chulalongkorn University 2012 November 28 Serbia University of Belgrade Thailand Suranaree University of Technology 2015 August 17 Europe The AGH University of Chiang Mai University 2015 December 10 Poland Science and Technology 2018 September 19 Lunghwa University of Science 2005 July 15 Faculty of Taiwan and Technology Education and Asia Korea Korean Language School 2019 January 28 National -

Back on the Tourist Trail After Almost 20 Years, Yangon

FLY MYANMAR ORNING COMES early here. By 5am, the streets are full of vendors, all getting ready to cook breakfast for the city’s hungry workforce. Chai is the country’s GOLDEN morning drink of choice and is served in small glass cups, steaming hot and very sweet. !e little wooden chairs outside the vendors’ stalls are soon filled, as men and sarong-clad women stop for a hot drink before getting on with their day. MOMENTS It is a familiar scene in many cities across Asia, but this is not one of the continent’s more well-known visi- Yangon tor locales, such as Bangkok, Hanoi or even Beijing. Rangoon !is is Yangon, formerly known as Rangoon and, not Myanmar TEXT/ CORI HOWARD so long ago, the capital of Myanmar, a country still Burma more familiar to many as Burma. 2006 Supplanted by Naypyidaw as the country’s capital in Back on the tourist trail after almost 2006, Yangon remains Myanmar’s busiest and most 20 populous city. It is getting used to welcoming visitors 20 years, Yangon offers a whole new again, with various political wranglings, both domesti- generation a wonderful taste of cally and internationally, keeping it off the tourist trail for almost 20 years. Myanmar’s culture, cuisine and history !e drive from the gleaming, new international air- port into Yangon takes you through dusty, bustling roads where street hawkers sell piles of old shoes and 20 women walk by balancing heavily laden baskets of fruit on their heads. Barefoot monks in saffron robes shade their shaved heads from the hot sun with rattan fans, while bare-chested men in sarongs pedal rickshaws alongside diesel-belching buses and the occasional, somewhat incongruous, brand-new SUV. -

Neil Sowards

NEIL SOWARDS c 1 LIFE IN BURMA © Neil Sowards 2009 548 Home Avenue Fort Wayne, IN 46807-1606 (260) 745-3658 Illustrations by Mehm Than Oo 2 NEIL SOWARDS Dedicated to the wonderful people of Burma who have suffered for so many years of exploitation and oppression from their own leaders. While the United Nations and the nations of the world have made progress in protecting people from aggressive neighbors, much remains to be done to protect people from their own leaders. 3 LIFE IN BURMA 4 NEIL SOWARDS Contents Foreword 1. First Day at the Bazaar ........................................................................................................................ 9 2. The Water Festival ............................................................................................................................. 12 3. The Union Day Flag .......................................................................................................................... 17 4. Tasty Tagyis ......................................................................................................................................... 21 5. Water Cress ......................................................................................................................................... 24 6. Demonetization .................................................................................................................................. 26 7. Thanakha ............................................................................................................................................ -

ASEAN University Network/ Southeast Asia Engineering Education

ASEAN University Network/ Southeast Asia Engineering Education Development Network AUN/SEED-Net Secretariat Room 109-110, Building 2, Faculty of Engineering, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok 10330, Thailand Tel: +66 2218 6419 to 21 Fax: +66 2218 6418 E-mail: [email protected] Introduction AUN/SEED-Net was established in 2001 as a sub program of AUN. It consists of universities as shown below and aims to establish a region–wide system for advanced research and education by these universities in ASEAN and Japan. The project is mainly supported by the Japanese government through JICA. 26 Member • University of Yangon (UY) Institutions in •National University of Laos • Yangon Technological University ASEAN Countries (NUOL) (YTU) • Hanoi University of Science and Technology 14 Japanese (HUST) Supporting • Ho Chi Minh City University of Technology • Chulalongkorn University (CU) (HCMUT) Universities • King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology Ladkrabang • Hokkaido University (Hokkaido) (KMITL) • University of the Philippines – Diliman • Keio University (Keio) • Burapha University (BUU) (UP) • Kyoto University (Kyoto) • Kasetsart University (KU) • De La Salle University (DLSU) • Kyushu University (Kyushu) • Thammasat University (TU) • Mindanao State University – Iligan • Nagoya University (Nagoya) Institute of Technology (MSU-IIT) • National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies (GRIPS) • Institute of Technology of • Universiti Brunei Darussalam • Osaka University (Osaka) Cambodia (ITC) (UBD) • Shibaura Institute of • Universiti Teknologi Brunei -

Participation of Myanmar Females in Science and Arts : Gender Impact of Science and Arts at University of Yangon

Participation of Myanmar Females in Science and Arts : Gender Impact of Science and Arts at University of Yangon Dr Mya Kay Thi Aung Lecturer Department of Chemistry, University of Yangon, Yangon, Myanmar (27-8-2015) Participation of Myanmar Females in Science and Arts : Gender Impact of Science and Arts at University of Yangon ABSTRACT Once ago, especially in education, Myanmar females have been kept at home for looking after younger siblings and older people so most of Myanmar females in the previous time were illiterate. However, at present, they have better opportunities of enrollment in education. In this present study of education in Myanmar, compared to the ratio of Myanmar population, more women than men, are found in most of the educational sectors as not only the learners of higher education, but also as the outstanding scientists as well as professionals. The main targeted groups of concern in gender analysis are both science and arts of teaching staff as well as researchers and outstanding undergraduate students in University of Yangon, Yangon, Myanmar between 2013 and 2015. Resembling the dominance of women in our country’s population, the female educators in our university also outweigh these of males in almost all of the sectors even though most of the top administrators are men. All in all, most of the males in the majority of the professional institutes have much better opportunities in enrolling these institutes or universities. Thus, males have better opportunities regarding with their matriculation marks for university -

Mikael Gravers Is Associate Professor Emeritus in Anthropology at Aarhus University, Denmark

About the Authors: Mikael Gravers is Associate Professor Emeritus in Anthropology at Aarhus University, Denmark. He has been conducting fieldwork in Thailand and Burma since 1970. He has done research among Buddhist and Christian Karen, in Buddhist monasteries, and in Hindu and Muslim communities. He is the author of Nationalism as Political Paranoia (1999) and edited Exploring Ethnic Diversity in Burma (2007). In 2014, he co-edited Burma/Myanmar – Where Now (with Flemming Ytzen). He has published on ethnicity, nationalism, Buddhism and politics, as well as on nature, culture and environmental protection. He has conducted research related to Burma in the colonial archives, in the British Library and at the Public Record Office, London. Before retirement, he was involved in organizing an international masters degree in Human Security at Aarhus University and he lectured on this subject until 2019. Annika Pohl Harrisson has a PhD from the Department of Anthropology at Aarhus University. She has conducted ethnographic research in Thailand and Myanmar. Annika is particularly interested in the localized production of legitimacy, everyday justice provision, and state-society relations. Her doctoral research investigates how different forms of state- making in southeast Myanmar affect the way in which sociality and subjectivities are constituted in everyday life. Her publications include (with Helene Maria Kyed) ‘Ceasefire state- making and justice provision by ethnic armed groups in southeast Myanmar’ (published in Sojourn 2019) and ‘Fish caught in clear water: Encompassed state-making in southeast Myanmar’ (published in Territory, Politics, Governance 2020). Lue Htar is currently a research manager at the Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation (EMReF), an independent research organization in Myanmar. -

Buddhism, Power and Political Order

BUDDHISM, POWER AND POLITICAL ORDER Weber’s claim that Buddhism is an otherworldly religion is only partially true. Early sources indicate that the Buddha was sometimes diverted from supra- mundane interests to dwell on a variety of politically related matters. The significance of Asoka Maurya as a paradigm for later traditions of Buddhist kingship is also well attested. However, there has been little scholarly effort to integrate findings on the extent to which Buddhism interacted with the polit- ical order in the classical and modern states of Theravada Asia into a wider, comparative study. This volume brings together the brightest minds in the study of Buddhism in Southeast Asia. Their contributions create a more coherent account of the relations between Buddhism and political order in the late pre-modern and modern period by questioning the contested relationship between monastic and secular power. In doing so, they expand the very nature of what is known as the ‘Theravada’. This book offers new insights for scholars of Buddhism, and it will stimulate new debates. Ian Harris is Professor of Buddhist Studies at the University of Cumbria, Lancaster, and was Senior Scholar at the Becket Institute, St Hugh’s College, University of Oxford, from 2001 to 2004. He is co-founder of the UK Association for Buddhist Studies and has written widely on aspects of Buddhist ethics. His most recent book is Cambodian Buddhism: History and Practice (2005), and he is currently responsible for a research project on Buddhism and Cambodian Communism at the Documentation Center of Cambodia [DC-Cam], Phnom Penh. ROUTLEDGE CRITICAL STUDIES IN BUDDHISM General Editors: Charles S. -

The Journal of Burma Studies

The Journal of Burma Studies Volume 8 2003 Featuring Articles by: Susanne Prager Megan Clymer Emma Larkin The Journal of Burma Studies President, Burma Studies Group F.K. Lehman General Editor Catherine Raymond Center for Burma Studies, Northern Illinois University Production Editor Peter Ross Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Northern Illinois University Publications Assistants Beth Bjorneby Mishel Filisha The Journal of Burma Studies is an annual scholarly journal jointly sponsored by the Burma Studies Group (Association for Asian Studies), The Center for Burma Studies (Northern Illinois University), and Northern Illinois University’s Center for Southeast Asian Studies. Articles are refereed by professional peers. Send one copy of your original scholarly manuscript with an electronic file. Mail: The Editor, Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, IL 60115. Email: [email protected]. Subscriptions are $16 per volume delivered book rate (Airmail add $10 per volume). Members of the Burma Studies Group receive the journal as part of their $25 annual membership. Send check or money order in U.S. dollars drawn on a U.S. bank made out to "Northern Illinois University" to Center of Burma Studies, Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, IL 60115. Visa and Mastercard orders also accepted. Subscriptions Tel: (815) 753-0512 Fax: (815) 753-1651 E-Mail: [email protected] Back Issues: seap@niu Tel: (815) 756-1981 Fax: (815) 753-1776 E-Mail: [email protected] For abstracts of forthcoming articles, visit The Journal of Burma -

Imagining the Buddhist Ecumene in Myanmar: How Buddhist Paradigms Dictate Belonging in Contemporary Myanmar

Imagining the Buddhist Ecumene in Myanmar: How Buddhist Paradigms Dictate Belonging in Contemporary Myanmar Daniel P. Murphree A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in International Studies: Southeast Asia University of Washington 2017 Committee: Laurie J. Sears Jenna M. Grant Timothy J. Lenz Program Authorized to Offer Degree: The Jackson School of International Studies ©Copyright 2017 Daniel P. Murphree University of Washington Abstract Imagining the Buddhist Ecumene in Myanmar: How Buddhist Paradigms Dictate Belonging in Contemporary Myanmar Daniel P. Murphree Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Walker Family Endowed Professor in History Laurie Sears Department of History This paper argues that the model of an “Ecumene” will aid external interpretation of the Myanmar political process, including the beliefs of its leaders and constituents, the Bamar. Myanmar as Ecumene better articulates Bama constructions of society, including governance, in that it resituates the political process as a Buddhist enterprise, shifting “Buddhist nationalism” to an imagined “Nation of Buddhists.” It also provides the rational for othering of religious minorities, such as the Muslim Rohingya or the Christian Chin. Utilizing ethnographic, historical, and textual source material, I show how the Bamar of Myanmar understand their relationship with the State, with one another, and with minority groups primarily through Buddhist modes of kingship and belonging. The right to rule is negotiated through the concept of “moral authority.” This dhamma sphere exists as a space to contest power legitimation, but requires the use of Buddhist textual and historical concepts provided in the dhammarāja or Cakkavattin model of Buddhist kingship, The Ten Virtues, the Jātakas, and the historical figures of Aśoka and Anawrahta. -

Burmese Law Tales the Legal Element in Burmese Folk-Lore

MAUNG HTIN AUNG Burmese Law Tales The Legal Element in Burmese Folk-lore LONDON Oxford University Press NEW YORK • BOMBAY • KUALA LUMPUR 1962 Oxford University Pressy Amen House, London e . c . GLASGOW NEW YORK TORONTO MELBOURNE WELLINGTON BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS KARACHI KUALA LUMPUR CAPE TOWN IBADAN NAIROBI ACCRA © Oxford University Press, 1962 MADE AND PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY THE CHAPEL RIVER PRESS LTD. AN DOVER. BANTS To my teacher of English Law, Miss F. E. Moran Regius Professor of Laws in The University of Dublin, this book is gratefully dedicated. v Preface When I was preparing the manuscript of my collection of Burmese Folk-Tales for publication in 1948, for some time I was unable to decide whether to include in that collection the Law Tales which are now given in the following pages. Finally, I decided that they should be left out because, first, I thought that they were borrowings from Hindu legal literature, and second, I thought that they had already been collected in the various Burmese legal writings. In both these assumptions I was wrong, and I was wrong because I then accepted the orthodox theory, first advanced by a European scholar of Burmese history1 that Burmese law was merely a derivation of Hindu law. After the publication of the Folk-Tales, I started my study of the Burmese legal writings (which still exist in hundreds in palm-leaf manuscript in the National Library, Rangoon), and I soon made the discovery that of the 65 Law Tales, only 28 were to be found in Burmese legal literature and of these 28, many were found merely as outlines and not as full-length stories.