How Effective Were the Suffragist and Suffragette Campaigns?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Millicent Fawcett from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Millicent Fawcett From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Dame Millicent Garrett Fawcett, GBE (11 June 1847 – 5 August 1929) was an English feminist, intellectual, political and union leader, and writer. She is primarily known for her work as a campaigner for women to have Millicent Fawcett the vote. GBE As a suffragist (as opposed to a suffragette), she took a moderate line, but was a tireless campaigner. She concentrated much of her energy on the struggle to improve women's opportunities for higher education and in 1875 cofounded Newnham College, Cambridge.[1] She later became president of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (the NUWSS), a position she held from 1897 until 1919. In July 1901 she was appointed to lead the British government's commission to South Africa to investigate conditions in the concentration camps that had been created there in the wake of the Second Boer War. Her report corroborated what the campaigner Emily Hobhouse had said about conditions in the camps. Contents 1 Early life 2 Married life 3 Later years 4 Political activities Born Millicent Garrett 5 Works 11 June 1847 6 See also Aldeburgh, England, United Kingdom 7 References 8 Archives Died 5 August 1929 (aged 82) 9 External links London, England, United Kingdom Nationality British Occupation Feminist, suffragist, union leader Early life Millicent Fawcett was born on 11 June 1847 in Aldeburgh[2] to Newson Garrett, a warehouse owner from Leiston, Suffolk, and his wife, Louisa née Dunnell (1813–1903), from London.[3][4] The Garrett ancestors had been ironworkers in East Suffolk since the early seventeenth century.[5] Newson Garrett was the youngest of three sons and not academically inclined, although he possessed the family’s entrepreneurial spirit. -

Process Paper and Bibliography

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Primary Sources Books Kenney, Annie. Memories of a Militant. London: Edward Arnold & Co, 1924. Autobiography of Annie Kenney. Lytton, Constance, and Jane Warton. Prisons & Prisoners. London: William Heinemann, 1914. Personal experiences of Lady Constance Lytton. Pankhurst, Christabel. Unshackled. London: Hutchinson and Co (Publishers) Ltd, 1959. Autobiography of Christabel Pankhurst. Pankhurst, Emmeline. My Own Story. London: Hearst’s International Library Co, 1914. Autobiography of Emmeline Pankhurst. Newspaper Articles "Amazing Scenes in London." Western Daily Mercury (Plymouth), March 5, 1912. Window breaking in March 1912, leading to trials of Mrs. Pankhurst and Mr. & Mrs. Pethick- Lawrence. "The Argument of the Broken Pane." Votes for Women (London), February 23, 1912. The argument of the stone: speech delivered by Mrs Pankhurst on Feb 16, 1912 honoring released prisoners who had served two or three months for window-breaking demonstration in November 1911. "Attempt to Burn Theatre Royal." The Scotsman (Edinburgh), July 19, 1912. PM Asquith's visit hailed by Irish Nationalists, protested by Suffragettes; hatchet thrown into Mr. Asquith's carriage, attempt to burn Theatre Royal. "By the Vanload." Lancashire Daily Post (Preston), February 15, 1907. "Twenty shillings or fourteen days." The women's raid on Parliament on Feb 13, 1907: Christabel Pankhurst gets fourteen days and Sylvia Pankhurst gets 3 weeks in prison. "Coal That Cooks." The Suffragette (London), July 18, 1913. Thirst strikes. Attempts to escape from "Cat and Mouse" encounters. "Churchill Gives Explanation." Dundee Courier (Dundee), July 15, 1910. Winston Churchill's position on the Conciliation Bill. "The Ejection." Morning Post (London), October 24, 1906. 1 The day after the October 23rd Parliament session during which Premier Henry Campbell- Bannerman cold-shouldered WSPU, leading to protest led by Mrs Pankhurst that led to eleven arrests, including that of Mrs Pethick-Lawrence and gave impetus to the movement. -

Download Issue

YOUTH &POLICY No. 116 MAY 2017 Youth & Policy: The final issue? Towards a new format Editorial Group Paula Connaughton, Ruth Gilchrist, Tracey Hodgson, Tony Jeffs, Mark Smith, Jean Spence, Naomi Thompson, Tania de St Croix, Aniela Wenham, Tom Wylie. Associate Editors Priscilla Alderson, Institute of Education, London Sally Baker, The Open University Simon Bradford, Brunel University Judith Bessant, RMIT University, Australia Lesley Buckland, YMCA George Williams College Bob Coles, University of York John Holmes, Newman College, Birmingham Sue Mansfield, University of Dundee Gill Millar, South West Regional Youth Work Adviser Susan Morgan, University of Ulster Jon Ord, University College of St Mark and St John Jenny Pearce, University of Bedfordshire John Pitts, University of Bedfordshire Keith Popple, London South Bank University John Rose, Consultant Kalbir Shukra, Goldsmiths University Tony Taylor, IDYW Joyce Walker, University of Minnesota, USA Anna Whalen, Freelance Consultant Published by Youth & Policy, ‘Burnbrae’, Black Lane, Blaydon Burn, Blaydon on Tyne NE21 6DX. www.youthandpolicy.org Copyright: Youth & Policy The views expressed in the journal remain those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Editorial Group. Whilst every effort is made to check factual information, the Editorial Group is not responsible for errors in the material published in the journal. ii Youth & Policy No. 116 May 2017 About Youth & Policy Youth & Policy Journal was founded in 1982 to offer a critical space for the discussion of youth policy and youth work theory and practice. The editorial group have subsequently expanded activities to include the organisation of related conferences, research and book publication. Regular activities include the bi- annual ‘History of Community and Youth Work’ and the ‘Thinking Seriously’ conferences. -

Making Exceptions to Universal Suffrage: Disability and the Right to Vote

Making Exceptions to Universal Suffrage: Disability and the Right to Vote Kay Schriner, University of Arkansas Lisa Ochs, Arkansas State University In C.E. Faupel & P.M. Roman (Eds.), Encyclopedia of criminology and deviant behavior 179-183. London: Taylore & Francis. 2000. The history of Western representative democracies is marked by disputes over who constitutes the electorate. In the U.S., where states have the prerogative of establishing voter qualifications, categories such as race and gender have been used during various periods to disqualify millions of individuals from participating in elections. These restrictions have long been considered an infamous example of the failings of democratic theorists and practitioners to overcome the prejudices of their time. Less well-known is the common practice of disenfranchising other large numbers of adults. Indeed, very few American citizens are aware that there are still two groups who are routinely targeted for disenfranchisement - criminals and individuals with disabilities. These laws, which arguably perpetuate racial and disability discrimination, are vestiges of earlier attempts to cordon off from democracy those who were believed to be morally and intellectually inferior. This entry describes these disability-based disenfranchisements, and briefly discusses the political, economic, and social factors associated with their adoption. Disenfranchising People with Cognitive and Emotional Impairments Today, forty-four states disenfranchise some individuals with cognitive and emotional impairments. States use a variety of categories to identify such individuals, including idiot, insane, lunatic, mental incompetent, mental incapacitated, being of unsound mind, not quiet and peaceable, and under guardianship and/or conservatorship. Fifteen states disenfranchise individuals who are idiots, insane, and/or lunatics. -

The Battle of Equality Contents 1

The Battle Of Equality Contents 1. Contents 2. Women’s Rights 3. 10 Famous women who made women’s suffrage happen. 4. Suffragettes 5. Suffragists 6. Who didn’t want women’s suffrage 7. Time Line of The Battle of Equality 8. Horse Derby 9. Pictures Woman’s Rights There were two groups that fought for woman's rights, the WSPU and the NUWSS. The NUWSS was set up by Millicent Fawcett. The WSPU was set up by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters. The WSPU was created because they didn’t want to wait for women’s rights by campaigning and holding petitions. They got bored so they created the WSPU. The WSPU went to the extreme lengths just to be heard. Whilst the NUWSS jus campaigned for women’s rights. 10 Famous women who made women’s suffrage happen. Emmeline Pankhurst (suffragette) - Leader of the suffragettes Christabel Pankhurst (suffragette)- Director of the most dangerous suffragette activities Constance Lytton (suffragette)- Daughter of viceroy Robert Bulwer-Lytton Emily Davison (suffragette)- Killed by kings horse Millicent Fawcett (suffragist)- Leader of the suffragist Edith Garrud (suffragette)- World professional Jiu-Jitsu master Silvia Pankhurst (suffragist)- Focused on campaigning and got expelled from the suffragettes by her sister Ethel Smyth (suffragette)- Conducted the suffragette anthem with a toothbrush Leonora Cohen (suffragette)- Smashed the display case for the Crown Jewels Constance Markievicz (suffragist)- Played a prominent role in ensuring Winston Churchill was defeated in elections Suffragettes The suffragettes were a group of women who wanted to vote. They did dangerous things like setting off bombs. The suffragettes were actually called The Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). -

The 2020 White Paper "Young Voices at the Ballot Box"

YOUNG VOICES AT THE BALLOT BOX Amplifying Youth Activism to Lower the Voting Age in 2020 and Beyond A White Paper from Generation Citizen (Version 3.0 – Feb. 2020) Young Voices at the Ballot Box: Amplifying Youth Activism to Lower the Voting Age 1 Young Voices at the Ballot Box: Amplifying Youth Activism to Lower the Voting Age 2 CONTENTS 03 Executive Summary 04 Why Should We Lower the Voting Age to 16? 08 Myths About Lowering the Voting Age 09 Current Landscape in the United States 17 Current Landscape Internationally 18 Next Steps to Advance this Cause 20 Conclusion 21 Appendix A: Countries with a Voting Age Lower than 18 22 Appendix B: Legal Feasibility of City Campaigns to Lower the Voting Age 34 Appendix C: Vote16USA Youth Advisory Board 35 Appendix D: Acknowledgements Cover Photo: Youth leaders, elected officials, and allies rally for a lower voting age on the steps of the California State Capitol in August 2019. Photo courtesy of Devin Murphy, California League of Conservation Voters. Young Voices at the Ballot Box: Amplifying Youth Activism to Lower the Voting Age 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY BY EXPANDING THE RIGHT TO VOTE [TO 16- AND 17-YEAR-OLDS], MY COMMUNITY WILL BE ABLE TO FURTHER CREATE AN ATMOSPHERE “WHERE EACH NEW GENERATION GROWS UP TO BE LIFE-LONG VOTERS, WITH THE VALUE OF CIVIC ENGAGEMENT INSTILLED IN THEM. - Megan Zheng Vote16USA Youth Advisory Board Member e are on a mission to lower the voting possible. Sixteen is. As this paper outlines, age to 16. Democracy only works when inviting citizens into the voting booth at 16” will Wcitizens participate; yet, compared to strengthen American democracy by establishing other highly developed, democratic countries, voting as a lifelong habit among all citizens, and the U.S. -

Item Captions Teachers Guide

SUFFRAGE IN A BOX: ITEM CAPTIONS TEACHERS GUIDE 1 1 The Polling Station. (Publisher: Suffrage Atelier). 1 Suffrage campaigners were experts in creating powerful propaganda images which expressed their sense of injustice. This image shows the whole range of women being kept out of the polling station by the law and authority represented by the policeman. These include musicians, clerical workers, mothers, university graduates, nurses, mayors, and artists. The men include gentlemen, manual workers, and agricultural labourers. This hints at the class hierarchies and tensions which were so important in British society at this time, and which also influenced the suffrage movement. All the women are represented as gracious and dignified, in contrast to the men, who are slouching and casual. This image was produced by the Suffrage Atelier, which brought together artists to create pictures which could be quickly and easily reproduced. ©Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford: John Johnson Collection; Postcards 12 (385) Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford John Johnson Collection; Postcards 12 (385) 2 The late Miss E.W. Davison (1913). Emily Wilding Davison is best known as the suffragette who 2 died after being trampled by the King’s horse on Derby Day, but as this photo shows, there was much more to her story. She studied at Royal Holloway College in London and St Hugh’s College Oxford, but left her job as a teacher to become a full- time suffragette. She was one of the most committed militants, who famously hid in a cupboard in the House of Commons on census night, 1911, so that she could give this as her address, and was the first woman to begin setting fire to post boxes. -

Lessons Learned from the Suffrage Movement

University of Baltimore Law ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 6-3-2020 Lessons Learned From the Suffrage Movement Margaret E. Johnson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac Part of the Law Commons Johnson, Margaret 6/3/2020 For Educational Use Only LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE SUFFRAGE MOVEMENT, 2 No. 1 Md. B.J. 115 2 No. 1 Md. B.J. 115 Maryland Bar Journal 2020 Margaret E. Johnsona1 PROFESSOR OF LAW, ASSOCIATE DEAN FOR EXPERIENTIAL EDUCATION, UNIVERSITY OF BALTIMORE SCHOOL OF LAW Copyright © 2020 by Maryland Bar Association; Margaret E. Johnson LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE SUFFRAGE MOVEMENT “Aye.” And with that one word, Tennessee Delegate Harry Burn changed his vote to one in favor of ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment after receiving a note from his mother stating “‘Hurrah and vote for suffrage .... don’t forget to be a good boy ....”’1 *116 With Burn’s vote on August 18, 1920, Tennessee became the thirty-sixth state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, paving the way for its adoption.2 The Nineteenth Amendment protects the female citizens’ constitutional right to vote.3 Prior to its passage, only a few states permitted women to vote in state and/or local elections.4 In 2020, we celebrate the Centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment’s passage. This anniversary provides a time to reflect upon lessons learned from the suffrage movement including that (1) voting rights matter; (2) inclusive movements matter; and (3) voting rights matter for, but cannot solely achieve, gender equality. -

Annotated Bibliography

Annotated Bibliography Primary Sources: Anonymous, “Women's Suffrage: The Right to The Vote”, n.d. This image shows an example of a poster that supported the Suffragettes’ cause. There have been numerous posters with a similar design. On this poster is Joan of Arc, an important figure to the Suffragettes, holding a banner that says “The Right to The Vote”. “ALL THE SUFFRAGIST LEADERS ARRESTED: “WE WILL ALL STARVE TO DEATH IN PRISON UNLESS WE ARE FORCIBLY FED”” The Daily Sketch, http://www.spirited.org.uk/object/daily-sketch-shows-the-method-used-for-force-feeding-suf fragettes This is an image of a newspaper during the force-feeding of Suffragettes. This image describes the strength and sacrifice that Suffragettes were willing to make. Barratt's Photo Press Ltd. “Suffragette Struggling with a Policeman on Black Friday.” The Museum of London, London , 14 Nov. 2018, www.museumoflondon.org.uk/discover/black-friday. This photograph was taken during the police brutality during protests against the failure of the Conciliation Bill. It was compiled by Barratt’s Photo Press Ltd. in 1910. Bathurst, G. “The National Archives .” Received by First Commissioner of His Majesty’s Works, The National Archives , 6 Apr. 1910. WORK 11/117, www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/suffragettes-on-file/hiding-in-parliament/. This was a letter written by G. Bathurst, Chief Clark of the Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis, to inform the First Commissioner of His Majesty’s Works about the actions of Emily Wilding Davison. Emily Wilding Davison was an important Suffragette who eventually became the Suffragette martyr in 1913 when she ran in front of the King’s horse during a derby. -

What Is Suffrage? by Gwen Perkins, Edited by Abby Rhinehart

What is Suffrage? by Gwen Perkins, edited by Abby Rhinehart "Suffrage" means the right to vote. When citizens have the right to vote for or against laws and leaders, that government is called a "democracy." Voting is one of the most important principles of government in a democracy. Many Americans think voting is an automatic right, something that all citizens over the age of 18 are guaranteed. But this has not always been the case. When the United States was founded, only white male property owners could vote. It has taken centuries for citizens to achieve the rights that they enjoy today. Who has been able to vote in United States history? How have voting rights changed over time? Read more to discover some key events. 1789: Religious Freedom When the nation was first founded, several of the 13 colonies did not allow Jews, Quakers, and/or Catholics to vote or run for political office. Article VI of the Constitution was written and adopted in 1789, granting religious freedom. This allowed white male property owners of all religions to vote and run for political office. 1870: Men of All Races Get the Right to Vote At the end of the Civil War, the United States created another amendment that gave former male slaves the right to vote. The 15th Amendment granted all men in the United States the right to vote regardless of "race, color, or previous condition of servitude." This sounded good, but there was a catch. To vote in many states, people were still required to own land. -

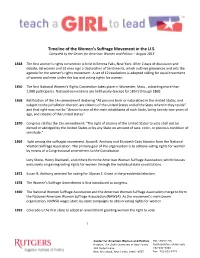

Timeline of the Women's Suffrage Movement in the U.S

Timeline of the Women’s Suffrage Movement in the U.S. Compiled by the Center for American Women and Politics – August 2014 1848 The first women's rights convention is held in Seneca Falls, New York. After 2 days of discussion and debate, 68 women and 32 men sign a Declaration of Sentiments, which outlines grievances and sets the agenda for the women's rights movement. A set of 12 resolutions is adopted calling for equal treatment of women and men under the law and voting rights for women. 1850 The first National Women's Rights Convention takes place in Worcester, Mass., attracting more than 1,000 participants. National conventions are held yearly (except for 1857) through 1860. 1868 Ratification of the 14th amendment declaring “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside” and that right may not be “denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State, being twenty-one years of age, and citizens of the United States” 1870 Congress ratifies the 15th amendment: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” 1869 Split among the suffragist movement. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton form the National Woman Suffrage Association. The primary goal of the organization is to achieve voting rights for women by means of a Congressional amendment to the Constitution. -

End Women's Suffrage- a Brief Study on Violence Against

Corpus Juris ISSN: 2582-2918 The Law Journal website: www.corpusjuris.co.in END WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE- A BRIEF STUDY ON VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN. - DEVANSH GULATI1 AND DHRUV CHAUHDHRY2 ABSTRACT The Global Campaign for elimination of violence against women in the past few years shows the evilness as well as the soberness of the malfeasance committed against women that are being witnessed in the whole world. There has been an increase in crime against women due to a change in the social ethos which contributes towards a violent attitude and tendency towards women. Crimes against women are said to be a matter of serious concern and it is a necessity that the women of India attain the rightful share of living with dignity, freedom, peace and last but not the least free from crimes. The struggle against crime towards women through various ways which could be in the form of Marital Rape, Domestic Violence, Sexual Exploitation, Assault etc. had started in the early ages by various sections of the society. There were many initiatives which were taken up in the form of campaigns and various social programmes along with social support and legal protection which safeguards and reforms in the Criminal Justice System. All these safeguards went in vain as these women in our country still suffer due to lack of awareness about their rights, due to illiteracy, oppressive practices and customs. There were many consequences regarding the same which amounted to fall in sex ratio, high infant mortality rate, low literacy rate, high dropout rate of girls from education, low wage rate etc.