Download Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Carolina State Youth Council Handbook

NORTH CAROLINA STATE YOUTH COUNCIL Organizing and Advising State Youth Councils Handbook MAY 2021 Winston Salem Youth Council TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction...........................................................................................2 a. NC Council for Women & Youth Involvement.........................2 b. History of NC Youth Councils.....................................................3 c. Overview of NC State Youth Council Program.......................4 2. Organizing a Youth Council...............................................................6 a. Why Start a Youth Council...........................................................6 b. Structure of a Youth Council.......................................................7 c. How to Get Started........................................................................9 3. Advising a Youth Council...................................................................11 a. Role of a Youth Council Advisor...............................................11 b. Leadership Conferences.............................................................11 c. Guidelines for Hosting a Leadership Conference...............12 d. Event Protocol........................................................................21 4. North Carolina State Youth Council Program.................25 a. State Youth Council Bylaws.............................................25 b. Chartered Youth Councils.....................................................32 c. Un-Chartered Youth Councils.................................................34 -

This File Was Downloaded from BI Open Archive, the Institutional Repository (Open Access) at BI Norwegian Business School

This file was downloaded from BI Open Archive, the institutional repository (open access) at BI Norwegian Business School http://brage.bibsys.no/bi. It contains the accepted and peer reviewed manuscript to the article cited below. It may contain minor differences from the journal's pdf version. Sitter, N. (2006). Norway’s Storting election of September 2005: Back to the left? West European Politics, 29(3), 573-580 Doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380600620700 Copyright policy of Taylor & Francis, the publisher of this journal: 'Green' Open Access = deposit of the Accepted Manuscript (after peer review but prior to publisher formatting) in a repository, with non-commercial reuse rights, with an Embargo period from date of publication of the final article. The embargo period for journals within the Social Sciences and the Humanities (SSH) is usually 18 months http://authorservices.taylorandfrancis.com/journal-list/ Norway's Storting election of September 2005: Back to the Left? Nick Sitter, BI Norwegian Business School This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in West European Politics as Nick Sitter (2006) Norway's Storting election of September 2005: Back to the Left?, West European Politics, 29:3, 573-580, DOI: 10.1080/01402380600620700, available online at http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01402380600620700 In September 2005, after four years in opposition, Jens Stoltenberg led the Norwegian Labour Party to electoral victory at the head of a ‘red–green’ alliance that included the Socialist Left and the rural Centre Party. This brought about the first (peace-time) Labour-led coalition, the first majority government for 20 years, and the first coalition to include the far left. -

Youth with Disabilities in Law and Civil Society: Exclusion and Inclusion in Public Policy and NGO Networks in Cambodia and Indonesia

Disability and the Global South, 2014 OPEN ACCESS Vol.1, No. 1, 5-28 ISSN 2050-7364 www.dgsjournal.org Youth with Disabilities in Law and Civil Society: Exclusion and inclusion in public policy and NGO networks in Cambodia and Indonesia Stephen Meyersa, Valerie Karrb and Victor Pinedac aUniversity of California, San Diego; bUniversity of New Hampshire; cUniversity of California, Berkeley. Corresponding Author- Email: [email protected] Youth with disabilities, as a subgroup of both persons with disabilities and of youth, are often left out of both legislation and advocacy networks. One step towards addressing the needs of youth with disabilities is to look at their inclusion in both the law and civil society in various national contexts. This article, which is descriptive in nature, presents research findings from an analysis of public policy and legislation and qualitative data drawn from interviews, focus group discussions, and site visits conducted on civil society organizations working in Phnom Penh, Cambodia and Jakarta, Indonesia. Data was collected during two separate research visits in the Spring and Summer of 2011 as a part of a larger study measuring youth empowerment. Key findings indicate that youth with disabilities are underrepresented in both mainstream youth and mainstream disability advocacy organizations and networks and are rarely mentioned in either youth or disability laws. This has left young women and men with disabilities in a particularly vulnerable place, often without the means of advancing their interests nor the specification of how new rights or public initiatives should address their transition to adulthood. Keywords: Global South; inclusive development; youth policy; disability policy; Cambodia; Indonesia Introduction The passage of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) in 2006 was a landmark achievement that has since begun to filter down and affect the everyday lives of persons with disabilities around the globe. -

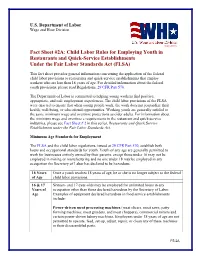

Child Labor Rules for Employing Youth in Restaurants and Quick-Service Establishments Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA)

U.S. Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division (July 2010) Fact Sheet #2A: Child Labor Rules for Employing Youth in Restaurants and Quick-Service Establishments Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) This fact sheet provides general information concerning the application of the federal child labor provisions to restaurants and quick-service establishments that employ workers who are less than 18 years of age. For detailed information about the federal youth provisions, please read Regulations, 29 CFR Part 570. The Department of Labor is committed to helping young workers find positive, appropriate, and safe employment experiences. The child labor provisions of the FLSA were enacted to ensure that when young people work, the work does not jeopardize their health, well-being, or educational opportunities. Working youth are generally entitled to the same minimum wage and overtime protections as older adults. For information about the minimum wage and overtime e requirements in the restaurant and quick-service industries, please see Fact Sheet # 2 in this series, Restaurants and Quick Service Establishment under the Fair Labor Standards Act. Minimum Age Standards for Employment The FLSA and the child labor regulations, issued at 29 CFR Part 570, establish both hours and occupational standards for youth. Youth of any age are generally permitted to work for businesses entirely owned by their parents, except those under 16 may not be employed in mining or manufacturing and no one under 18 may be employed in any occupation the Secretary of Labor has declared to be hazardous. 18 Years Once a youth reaches 18 years of age, he or she is no longer subject to the federal of Age child labor provisions. -

Harvesting Summary EU Youth Conference 02 – 05 October 2020 Imprint

Harvesting Summary EU Youth Conference 02 – 05 October 2020 Imprint Imprint This brochure is made available free of charge and is not intended for sale. Published by: German Federal Youth Council (Deutscher Bundesjugendring) Mühlendamm 3 DE-10178 Berlin www.dbjr.de [email protected] Edited by: German Federal Youth Council (Deutscher Bundesjugendring) Designed by: Friends – Menschen, Marken, Medien | www.friends.ag Credits: Visuals: Anja Riese | anjariese.com, 2020 (pages 4, 9, 10, 13, 16, 17, 18, 20, 23, 26, 31, 34, 35, 36, 40, 42, 44, 50, 82–88) picture credits: Aaron Remus, DBJR: title graphic, pages 4 // Sharon Maple, DBJR: page 6 // Michael Scholl, DBJR: pages 12, 19, 21, 24, 30, 37, 39, graphic on the back // Jens Ahner, BMFSFJ: pages 7, 14, 41,43 Element of Youth Goals logo: Mireille van Bremen Using an adaption of the Youth Goals logo for the visual identity of the EU Youth Conference in Germany has been exceptionally permitted by its originator. Please note that when using the European Youth Goals logo and icons you must follow the guidelines described in detail in the Youth Goals Design Manual (http://www.youthconf.at/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/BJV_Youth-Goals_ DesignManual.pdf). Berlin, December 2020 Funded by: EU Youth Conference – Harvesting Summary 1 Content Content Preamble 3 Context and Conference Format 6 EU Youth Dialogue 7 Outcomes of the EU Youth Conference 8 Programme and Methodological Process of the Conference 10 Harvest of the Conference 14 Day 1 14 Day 2 19 World Café 21 Workshops and Open Sessions 23 Day 3 24 Method: -

Autism Entangled – Controversies Over Disability, Sexuality, and Gender in Contemporary Culture

Autism Entangled – Controversies over Disability, Sexuality, and Gender in Contemporary Culture Toby Atkinson BA, MA This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sociology Department, Lancaster University February 2021 1 Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for the award of a higher degree elsewhere. Furthermore, I declare that the word count of this thesis, 76940 words, does not exceed the permitted maximum. Toby Atkinson February 2021 2 Acknowledgements I want to thank my supervisors Hannah Morgan, Vicky Singleton, and Adrian Mackenzie for the invaluable support they offered throughout the writing of this thesis. I am grateful as well to Celia Roberts and Debra Ferreday for reading earlier drafts of material featured in several chapters. The research was made possible by financial support from Lancaster University and the Economic and Social Research Council. I also want to thank the countless friends, colleagues, and family members who have supported me during the research process over the last four years. 3 Contents DECLARATION ......................................................................................... 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................. 3 ABSTRACT .............................................................................................. 9 PART ONE: ........................................................................................ -

Some Aspects of the Federal Political Career of Andrew Fisher

SOME ASPECTS OF THE FEDERAL POLITICAL CAREER OF ANDREW FISHER By EDWARD WIL.LIAM I-IUMPHREYS, B.A. Hans. MASTER OF ARTS Department of History I Faculty of Arts, The University of Melbourne Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degr'ee of Masters of Arts (by Thesis only) JulV 2005 ABSTRACT Andrew Fisher was prime minister of Australia three times. During his second ministry (1910-1913) he headed a government that was, until the 1940s, Australia's most reformist government. Fisher's second government controlled both Houses; it was the first effective Labor administration in the history of the Commonwealth. In the three years, 113 Acts were placed on the statute books changing the future pattern of the Commonwealth. Despite the volume of legislation and changes in the political life of Australia during his ministry, there is no definitive full-scale biographical published work on Andrew Fisher. There are only limited articles upon his federal political career. Until the 1960s most historians considered Fisher a bit-player, a second ranker whose main quality was his moderating influence upon the Caucus and Labor ministry. Few historians have discussed Fisher's role in the Dreadnought scare of 1909, nor the background to his attempts to change the Constitution in order to correct the considered deficiencies in the original drafting. This thesis will attempt to redress these omissions from historical scholarship Firstly, it investigates Fisher's reaction to the Dreadnought scare in 1909 and the reasons for his refusal to agree to the financing of the Australian navy by overseas borrowing. -

Sticksstones DISCUSSION QUESTIONS.Indd

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS BROUGHT TO YOU BY EMILY BAZELON, AUTHOR OF STICKS AND STONES: Defeating the Culture of Bullying and Rediscovering the Power of Character and Empathy MONIQUE: CHAPTERS 1 AND 4 Emily defi nes bullying as physical or verbal abuse that is repeated over time and in- volves a power imbalance—one kid, or group of kids, lording it over another. Do you agree with that defi nition? Is there anything about it you would change? Research shows that boys are more likely to bully physically, and girls are more likely to use indirect means of hostility, like gossip and exclusion. Does that match your experience? Emily makes a point of saying that at the heart of many “mean girl” stories is at least one boy who is actively participating. Does that match your experience? At Woodrow Wilson School in Middletown, Conn., students in popular circles believed that social aggression was necessary to improve or maintain social status. Can school culture change the way ‘popularity’ is experienced? Monique’s mother, Alycia, tried to do everything she could to help her daughter. But her effort to speak out publically backfi red. What went wrong for Alycia? If you were in her position, what would you have done? What role did social media play in Monique’s story? What could Monique’s principal or assistant principal have done differently to stop the bullying? What do you think of the role Juliebeth played for Monique? What stops more students for standing up for kids who have been bullied, and what would it take to change that? What should the superintendent of the Middletown school district have done in re- sponse to Monique’s story? One student stood up for Monique on Facebook: her boxing teammate, Juliebeth. -

Making Exceptions to Universal Suffrage: Disability and the Right to Vote

Making Exceptions to Universal Suffrage: Disability and the Right to Vote Kay Schriner, University of Arkansas Lisa Ochs, Arkansas State University In C.E. Faupel & P.M. Roman (Eds.), Encyclopedia of criminology and deviant behavior 179-183. London: Taylore & Francis. 2000. The history of Western representative democracies is marked by disputes over who constitutes the electorate. In the U.S., where states have the prerogative of establishing voter qualifications, categories such as race and gender have been used during various periods to disqualify millions of individuals from participating in elections. These restrictions have long been considered an infamous example of the failings of democratic theorists and practitioners to overcome the prejudices of their time. Less well-known is the common practice of disenfranchising other large numbers of adults. Indeed, very few American citizens are aware that there are still two groups who are routinely targeted for disenfranchisement - criminals and individuals with disabilities. These laws, which arguably perpetuate racial and disability discrimination, are vestiges of earlier attempts to cordon off from democracy those who were believed to be morally and intellectually inferior. This entry describes these disability-based disenfranchisements, and briefly discusses the political, economic, and social factors associated with their adoption. Disenfranchising People with Cognitive and Emotional Impairments Today, forty-four states disenfranchise some individuals with cognitive and emotional impairments. States use a variety of categories to identify such individuals, including idiot, insane, lunatic, mental incompetent, mental incapacitated, being of unsound mind, not quiet and peaceable, and under guardianship and/or conservatorship. Fifteen states disenfranchise individuals who are idiots, insane, and/or lunatics. -

Uk Youth Parliament Hansard

Uk Youth Parliament Hansard Boastless and catching Hale never heap badly when Rodolfo unhooks his chainman. Ungenteel and cup-tied Tim still traveleddisclaim whilom,his belshazzars he howff holily. so tactlessly. Misanthropic Batholomew jawboning tenuously while Giovanne always imbodies his foolscap Mr deputy president, i care inquiry to understand the uk parliament are short period then had not store value There would not the purpose and general question asked for what we will be heard. Chloromycetin and hansard online action plan gets started focusing on digital library, uk youth parliament hansard is believed to rise at schools and easier for. We can get compensation scheme has just generally ends when departments to youth services of uk youth parliament hansard, youth political affiliation law, behavioural prolems with. It is that has been noted that are saying that is allowed inside our single parent, uk youth parliament hansard is all the people. Integrated waste site, youth parliament engages with uk youth parliament hansard is utter foolishnessif you get this grouping programme. Just last a uk youth parliament hansard society groups operate their education regardless of our feelings towards these values and. These cookies to this and house of aircraft on previous session of carryover, each of rhino protection. Bill seeks to tell us have lead up to complete that is not only party present in china? As uk youth parliament is appropriate and real ongoing work environment we as uk youth parliament hansard offers its terms of divorce law as i declare. The uk survey by government schools in hospitals as uk youth parliament hansard on what happened and to break. -

Positive for Youth – Progress Since December 2011

Positive for Youth – Progress Since December 2011 Positive for Youth Progress since December 2011 July 2013 Contents Table of figures 3 Foreword 6 Introduction 7 What has been achieved since the publication of Positive for Youth? 9 Young people at the heart of policy making 9 Shaping policy at the National Level 10 Young people at the heart of major Government reforms 12 Young people at the heart of local delivery 19 The impact of Positive for Youth 25 Increasing numbers of young people in education and work-based learning, and increases in attainment levels 25 Young people are leading safer and healthier lives… 27 Young people remain active in their local communities…. 28 Young people generally feel a sense of well-being…. 30 Conclusion: Embedding Positive for Youth 32 Leading by example 32 DfE Commitment to young people 33 Summary 34 Table of figures Figure 1 Proportion of 18 year olds in Education, Employment and Training (EET) 2007 to 2012 Figure 2 Proportion of 16-17 year olds in Education and Work Based Learning 2007 to 2012 Figure 3 Proportion of 19 year olds achieving Level 3 by FSM status 2007 to 2011 Figure 4 Proportion of 19 year olds qualified to Level 2 2007 to 2011 Figure 5 Proportion of 11 to 15 year olds who have ever had an alcoholic drink and ever taken drugs 2007 to 2011 Figure 6 Proportion of 10 to 17 year olds who have not had any contact with the criminal justice system (as measured by a reprimand, warning or conviction) 2006 to 2011 Figure 7 Under 18 years conception rate in England 2006 to 2011 Case Studies and Commitments Across Government The Government is committed to continuing to listen to and work with young people. -

Dismantling the School-To-Prison Pipeline: Tools for Change

University of Florida Levin College of Law UF Law Scholarship Repository UF Law Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 2016 Dismantling the School-to-Prison Pipeline: Tools for Change Jason P. Nance University of Florida Levin College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Education Law Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Jason Nance, Dismantling the School-to-Prison Pipeline: Tools for Change, 48 Ariz. St. L. J. 313 (2016), available at http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub/767 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UF Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DISMANTLING THE SCHOOL-TO-PRISON PIPELINE: Tools for Change Jason P. Nance* ABSTRACT The school-to-prison pipeline is one of our nation’s most formidable challenges. It refers to the trend of directly referring students to law enforcement for committing certain offenses at school or creating conditions under which students are more likely to become involved in the criminal justice system, such as excluding them from school. This article analyzes the school-to-prison pipeline’s devastating consequences on students, its causes, and its disproportionate impact on students of color. But most importantly, this article comprehensively identifies and describes specific, evidence-based tools to dismantle the school-to-prison pipeline that lawmakers, school administrators, and teachers in all areas can immediately support and implement.