The 2020 White Paper "Young Voices at the Ballot Box"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Issue

YOUTH &POLICY No. 116 MAY 2017 Youth & Policy: The final issue? Towards a new format Editorial Group Paula Connaughton, Ruth Gilchrist, Tracey Hodgson, Tony Jeffs, Mark Smith, Jean Spence, Naomi Thompson, Tania de St Croix, Aniela Wenham, Tom Wylie. Associate Editors Priscilla Alderson, Institute of Education, London Sally Baker, The Open University Simon Bradford, Brunel University Judith Bessant, RMIT University, Australia Lesley Buckland, YMCA George Williams College Bob Coles, University of York John Holmes, Newman College, Birmingham Sue Mansfield, University of Dundee Gill Millar, South West Regional Youth Work Adviser Susan Morgan, University of Ulster Jon Ord, University College of St Mark and St John Jenny Pearce, University of Bedfordshire John Pitts, University of Bedfordshire Keith Popple, London South Bank University John Rose, Consultant Kalbir Shukra, Goldsmiths University Tony Taylor, IDYW Joyce Walker, University of Minnesota, USA Anna Whalen, Freelance Consultant Published by Youth & Policy, ‘Burnbrae’, Black Lane, Blaydon Burn, Blaydon on Tyne NE21 6DX. www.youthandpolicy.org Copyright: Youth & Policy The views expressed in the journal remain those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Editorial Group. Whilst every effort is made to check factual information, the Editorial Group is not responsible for errors in the material published in the journal. ii Youth & Policy No. 116 May 2017 About Youth & Policy Youth & Policy Journal was founded in 1982 to offer a critical space for the discussion of youth policy and youth work theory and practice. The editorial group have subsequently expanded activities to include the organisation of related conferences, research and book publication. Regular activities include the bi- annual ‘History of Community and Youth Work’ and the ‘Thinking Seriously’ conferences. -

Making Exceptions to Universal Suffrage: Disability and the Right to Vote

Making Exceptions to Universal Suffrage: Disability and the Right to Vote Kay Schriner, University of Arkansas Lisa Ochs, Arkansas State University In C.E. Faupel & P.M. Roman (Eds.), Encyclopedia of criminology and deviant behavior 179-183. London: Taylore & Francis. 2000. The history of Western representative democracies is marked by disputes over who constitutes the electorate. In the U.S., where states have the prerogative of establishing voter qualifications, categories such as race and gender have been used during various periods to disqualify millions of individuals from participating in elections. These restrictions have long been considered an infamous example of the failings of democratic theorists and practitioners to overcome the prejudices of their time. Less well-known is the common practice of disenfranchising other large numbers of adults. Indeed, very few American citizens are aware that there are still two groups who are routinely targeted for disenfranchisement - criminals and individuals with disabilities. These laws, which arguably perpetuate racial and disability discrimination, are vestiges of earlier attempts to cordon off from democracy those who were believed to be morally and intellectually inferior. This entry describes these disability-based disenfranchisements, and briefly discusses the political, economic, and social factors associated with their adoption. Disenfranchising People with Cognitive and Emotional Impairments Today, forty-four states disenfranchise some individuals with cognitive and emotional impairments. States use a variety of categories to identify such individuals, including idiot, insane, lunatic, mental incompetent, mental incapacitated, being of unsound mind, not quiet and peaceable, and under guardianship and/or conservatorship. Fifteen states disenfranchise individuals who are idiots, insane, and/or lunatics. -

Lessons Learned from the Suffrage Movement

University of Baltimore Law ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 6-3-2020 Lessons Learned From the Suffrage Movement Margaret E. Johnson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac Part of the Law Commons Johnson, Margaret 6/3/2020 For Educational Use Only LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE SUFFRAGE MOVEMENT, 2 No. 1 Md. B.J. 115 2 No. 1 Md. B.J. 115 Maryland Bar Journal 2020 Margaret E. Johnsona1 PROFESSOR OF LAW, ASSOCIATE DEAN FOR EXPERIENTIAL EDUCATION, UNIVERSITY OF BALTIMORE SCHOOL OF LAW Copyright © 2020 by Maryland Bar Association; Margaret E. Johnson LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE SUFFRAGE MOVEMENT “Aye.” And with that one word, Tennessee Delegate Harry Burn changed his vote to one in favor of ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment after receiving a note from his mother stating “‘Hurrah and vote for suffrage .... don’t forget to be a good boy ....”’1 *116 With Burn’s vote on August 18, 1920, Tennessee became the thirty-sixth state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, paving the way for its adoption.2 The Nineteenth Amendment protects the female citizens’ constitutional right to vote.3 Prior to its passage, only a few states permitted women to vote in state and/or local elections.4 In 2020, we celebrate the Centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment’s passage. This anniversary provides a time to reflect upon lessons learned from the suffrage movement including that (1) voting rights matter; (2) inclusive movements matter; and (3) voting rights matter for, but cannot solely achieve, gender equality. -

How Effective Were the Suffragist and Suffragette Campaigns?

What were the arguments for and against female suffrage? Note: the proper name for votes for women is ‘Female Suffrage’ In the nineteenth century, new jobs emerged for women as teachers, as shop workers or as clerks and secretaries in offices. Many able girls from working-class backgrounds could achieve better-paid jobs than those of their parents. They had more opportunities in education., for example a few middle-class women won the chance to go to university, to become doctors. Laws between 1839 and 1886 gave married women greater legal rights. However, they could not vote in general elections. The number of men who could vote had gradually increased during the nineteenth century (see the Factfile). Some people thought that women should be allowed to vote too. Others disagreed. But the debate was not, simply a case of men versus women. How effective were the suffragist and suffragette campaigns? Who were the suffragists? The early campaigners for the vote were known as suffragists. They were mainly (though not all) middle-class women. When the MP John Stuart Mill had suggested giving votes to women in 1867, 73 MPs had supported it. After 1867, local groups set up by women called women’s suffrage societies were formed. By the time they came together in 1897 to form the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), there were over 500 local branches. By 1902, the campaign had gained the support of working-class women as well. In 1901–1902, Eva Gore-Booth gathered the signatures of 67,000 textile workers in northern England for a petition (signed letter) to Parliament. -

What Is Suffrage? by Gwen Perkins, Edited by Abby Rhinehart

What is Suffrage? by Gwen Perkins, edited by Abby Rhinehart "Suffrage" means the right to vote. When citizens have the right to vote for or against laws and leaders, that government is called a "democracy." Voting is one of the most important principles of government in a democracy. Many Americans think voting is an automatic right, something that all citizens over the age of 18 are guaranteed. But this has not always been the case. When the United States was founded, only white male property owners could vote. It has taken centuries for citizens to achieve the rights that they enjoy today. Who has been able to vote in United States history? How have voting rights changed over time? Read more to discover some key events. 1789: Religious Freedom When the nation was first founded, several of the 13 colonies did not allow Jews, Quakers, and/or Catholics to vote or run for political office. Article VI of the Constitution was written and adopted in 1789, granting religious freedom. This allowed white male property owners of all religions to vote and run for political office. 1870: Men of All Races Get the Right to Vote At the end of the Civil War, the United States created another amendment that gave former male slaves the right to vote. The 15th Amendment granted all men in the United States the right to vote regardless of "race, color, or previous condition of servitude." This sounded good, but there was a catch. To vote in many states, people were still required to own land. -

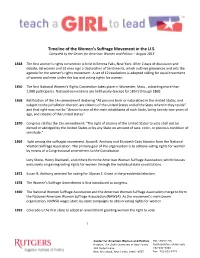

Timeline of the Women's Suffrage Movement in the U.S

Timeline of the Women’s Suffrage Movement in the U.S. Compiled by the Center for American Women and Politics – August 2014 1848 The first women's rights convention is held in Seneca Falls, New York. After 2 days of discussion and debate, 68 women and 32 men sign a Declaration of Sentiments, which outlines grievances and sets the agenda for the women's rights movement. A set of 12 resolutions is adopted calling for equal treatment of women and men under the law and voting rights for women. 1850 The first National Women's Rights Convention takes place in Worcester, Mass., attracting more than 1,000 participants. National conventions are held yearly (except for 1857) through 1860. 1868 Ratification of the 14th amendment declaring “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside” and that right may not be “denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State, being twenty-one years of age, and citizens of the United States” 1870 Congress ratifies the 15th amendment: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” 1869 Split among the suffragist movement. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton form the National Woman Suffrage Association. The primary goal of the organization is to achieve voting rights for women by means of a Congressional amendment to the Constitution. -

End Women's Suffrage- a Brief Study on Violence Against

Corpus Juris ISSN: 2582-2918 The Law Journal website: www.corpusjuris.co.in END WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE- A BRIEF STUDY ON VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN. - DEVANSH GULATI1 AND DHRUV CHAUHDHRY2 ABSTRACT The Global Campaign for elimination of violence against women in the past few years shows the evilness as well as the soberness of the malfeasance committed against women that are being witnessed in the whole world. There has been an increase in crime against women due to a change in the social ethos which contributes towards a violent attitude and tendency towards women. Crimes against women are said to be a matter of serious concern and it is a necessity that the women of India attain the rightful share of living with dignity, freedom, peace and last but not the least free from crimes. The struggle against crime towards women through various ways which could be in the form of Marital Rape, Domestic Violence, Sexual Exploitation, Assault etc. had started in the early ages by various sections of the society. There were many initiatives which were taken up in the form of campaigns and various social programmes along with social support and legal protection which safeguards and reforms in the Criminal Justice System. All these safeguards went in vain as these women in our country still suffer due to lack of awareness about their rights, due to illiteracy, oppressive practices and customs. There were many consequences regarding the same which amounted to fall in sex ratio, high infant mortality rate, low literacy rate, high dropout rate of girls from education, low wage rate etc. -

The Legacy of Woman Suffrage for the Voting Right

UCLA UCLA Women's Law Journal Title Dominance and Democracy: The Legacy of Woman Suffrage for the Voting Right Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4r4018j9 Journal UCLA Women's Law Journal, 5(1) Author Lind, JoEllen Publication Date 1994 DOI 10.5070/L351017615 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ARTICLE DOMINANCE AND DEMOCRACY: THE LEGACY OF WOMAN SUFFRAGE FOR THE VOTING RIGHT JoEllen Lind* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................ 104 I. VOTING AND THE COMPLEX OF DOMINANCE ......... 110 A. The Nineteenth Century Gender System .......... 111 B. The Vote and the Complex of Dominance ........ 113 C. Political Theories About the Vote ................. 116 1. Two Understandings of Political Participation .................................. 120 2. Our Federalism ............................... 123 II. A SUFFRAGE HISTORY PRIMER ...................... 126 A. From Invisibility to Organization: The Women's Movement in Antebellum America ............... 128 1. Early Causes ................................. 128 2. Women and Abolition ........................ 138 3. Seneca Falls - Political Discourse at the M argin ....................................... 145 * Professor of Law, Valparaiso University; A.B. Stanford University, 1972; J.D. University of California at Los Angeles, 1975; Candidate Ph.D. (political the- ory) University of Utah, 1994. I wish to thank Akhil Amar for the careful reading he gave this piece, and in particular for his assistance with Reconstruction history. In addition, my colleagues Ivan Bodensteiner, Laura Gaston Dooley, and Rosalie Levinson provided me with perspicuous editorial advice. Special acknowledgment should also be given to Amy Hague, Curator of the Sophia Smith Collection of Smith College, for all of her help with original resources. Finally, I wish to thank my research assistants Christine Brookbank, Colleen Kritlow, and Jill Norton for their exceptional contribution to this project. -

Can Detention Reduce Recidivism of Youth? an Outcome Evaluation

CAN DETENTION REDUCE RECIDIVISM OF YOUTH? AN OUTCOME EVALUATION OF A JUVENILE DETENTION CENTER A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the North Dakota State University of Agriculture and Applied Science By Tia Simanovic In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major Department: Criminal Justice and Political Science May 2017 Fargo, North Dakota North Dakota State University Graduate School Title CAN DETENTION REDUCE RECIDIVISM OF YOUTH? AN OUTCOME EVALUATION OF A JUVENILE DETENTION CENTER By Tia Simanovic The Supervisory Committee certifies that this disquisition complies with North Dakota State University’s regulations and meets the accepted standards for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Andrew J. Myer, PhD Chair Amy J. Stichman, PhD James E. Deal, PhD Approved: May 12, 2017 Jeffrey Bumgarner, PhD Date Department Chair ABSTRACT This study is an outcome evaluation of a secure unit of one juvenile detention center in the Midwest. The primary purpose of this study was to elucidate the relationship between a secure detention placement and recidivism on a sample of Midwest juvenile offenders. Besides the examination of recidivism of the total sample, this study examined differences between two subsamples of the institutionalized juveniles, those in a treatment program and those in detention only. The importance of demographics, prior admissions, length of stay, frequency of institutional misconduct, and exposure to treatment was examined. Results suggest a significant negative relationship between the age at admission and recidivism, and a positive one between prior admissions and recidivism. Length of stay, institutional misconduct, and treatment did not reach significance. -

Youth Suffrage: in Support of the Second Wave

Akron Law Review Volume 53 Issue 2 Nineteenth Amendment Issue Article 6 2019 Youth Suffrage: In Support of the Second Wave Mae C. Quinn Caridad Dominguez Chelsey Omega Abrafi Osei-Kofi Carlye Owens Follow this and additional works at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, and the Law and Gender Commons Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Recommended Citation Quinn, Mae C.; Dominguez, Caridad; Omega, Chelsey; Osei-Kofi, Abrafi; and Owens, Carlye (2019) "Youth Suffrage: In Support of the Second Wave," Akron Law Review: Vol. 53 : Iss. 2 , Article 6. Available at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol53/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Akron Law Journals at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The University of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Akron Law Review by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Quinn et al.: Youth Suffrage YOUTH SUFFRAGE: IN SUPPORT OF THE SECOND WAVE Mae C. Quinn*, Caridad Dominguez**, Chelsey Omega***, Abrafi Osei-Kofi****, and Carlye Owens∗∗∗∗∗ Introduction ......................................................................... 446 I. Youth Suffrage’s 20th Century First Wave—18 and Up to Vote ....................................................................... 449 A. 26th Amendment Ratification, Roll Out, and Rumblings of Resistance..................................... 449 B. Residency Requirements and Further Impediments for Student Voters ............................................... 452 C. Criminalization of Youth of Color and Poverty as Disenfranchisement Drivers............................... -

Overview of Women's Suffrage in the United States Compiled by the Center for American Women and Politics

Overview of Women's Suffrage in the United States Compiled by the Center for American Women and Politics Women in the Nineteenth Century For many women in the early nineteenth century, activity was limited to the domestic life of the home and care of the children. Women were dependent on the men in their lives, including fathers, husbands, or brothers. Once married, women did not have the right to own property, maintain their wages, or sign a contract, much less vote. In colonial America, most Black women were considered property. Women were expected to obey their husbands, not express opinions independent of, or counter to, their husbands’. It was considered improper for women to travel alone or to speak in public. Immigrant women, women of color, and low-income women nevertheless had to work outside the home, often in domestic labor or sweatshops. In the nineteenth century taking a job was considered neither respectable nor something that an “honest” woman would do, and women who did so were considered to have given up their claim to “gentle treatment” and were often exploited by their employers. The Seneca Falls Convention The women's suffrage movement was formally set into motion in July 1848 with the first Women's Rights Convention in Seneca Falls, New York. Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton were among the American delegation to attend the World Anti-Slavery Convention held in London in 1840. Because they were women, they were forced to sit in the galleries as observers. Upon returning home, they decided to hold their own convention to "discuss the social, civil and religious rights of women." Using the Declaration of Independence as a guide, Stanton drafted the Declaration of Sentiments which drew attention to women's subordinate status and made recommendations for change, including calling for women to have “immediate admission to all the rights and privileges which belong to them as these citizens of the United States.” After the Seneca Falls Convention, the demand for the vote became the centerpiece of the women's rights movement. -

Teacher Overview Objectives: Mandela and Apartheid

Teacher Overview Objectives: Mandela and Apartheid NYS Social Studies Framework Alignment: Key Idea Conceptual Understanding Content Specification Objective 10.10 HUMAN RIGHTS 10.10c Historical and contemporary Students will examine the policy of Describe the political, economic and VIOLATIONS: Since the Holocaust, violations of human rights can be apartheid in South Africa and the social characteristics of South Africa human rights violations have evaluated, using the principles and growth of the anti-apartheid under apartheid generated worldwide attention and articles established within the UN movements, exploring Nelson concern. The United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Mandela’s role in these movements Describe what evidence will be Universal Declaration of Human Rights. and in the post-apartheid period. needed to respond to the compelling Rights has provided a set of question. principles to guide efforts to protect threatened groups and has served Describe efforts made by Nelson as a lens through which historical Mandela as well as organizations occurrences of oppression can be within and outside of South Africa to evaluated. (Standards: 2, 5; Themes: end apartheid. ID, TCC, SOC, GOV, CIV) The following materials make use of resources and methodology of the New York State Social Studies Resource Toolkit. Please visit http://www.c3teachers.org/ to support this important effort, find the original sources, and explore other inquiries that align to the NYS Social Studies Framework. Staging the Compelling Question: What ended Apartheid? Supporting Question 1: What is Apartheid? Objectives: ● Describe the political, economic and social characteristics of South Africa under apartheid ● Describe what evidence will be needed to respond to the compelling question.