Kleist's Penthesilea As "Hundekomödie" Griffiths, Elystan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Positionings of Jewish Self

“SCHREIBEN WAS HIER WAR” BEYOND THE HOLOCAUST-PARADIGM: (RE)POSITIONINGS OF JEWISH SELF-IDENTITY IN GERMAN-JEWISH NARRATIVES PAST AND PRESENT by Martina Wells B.A equivalent, English and History, University of Mainz, Germany 1985 M.A., German Studies, University of Pittsburgh, 2008 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts & Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2015 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS & SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Martina Wells It was defended on March 31, 2015 and approved by Randall Halle, Klaus W. Jonas Professor of German Film and Cultural Studies, Department of German John B. Lyon, Associate Professor, Department of German Lina Insana, Associate Professor, Department of French & Italian Languages and Literatures Dissertation Advisor: Sabine von Dirke, Associate Professor, Department of German ii Copyright © by Martina Wells 2015 iii “SCHREIBEN WAS HIER WAR” BEYOND THE HOLOCAUST-PARADIGM: (RE)POSITIONINGS OF JEWISH SELF-IDENTITY IN GERMAN-JEWISH NARRATIVES PAST AND PRESENT Martina Wells, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2015 This dissertation examines the stakes of self-Orientalizing in literary and cinematographic texts of German-Jewish cultural producers in the context of Jewish emancipation and modernization. Positing Jewish emancipation as a trans-historical and cultural process, my study traces the poetic journey of a particular set of Orientalist tropes from 19th century ghetto stories to contemporary writings and film at the turn of the millennium to address a twofold question: what could this problematic method of representation accomplish for Germany’s Jewish minority in the past, and how do we understand its re-appropriation by Germany’s “new Jewry” today. -

Jiddistik Heute

לקט ייִ דישע שטודיעס הנט Jiddistik heute Yiddish Studies Today לקט Der vorliegende Sammelband eröffnet eine neue Reihe wissenschaftli- cher Studien zur Jiddistik sowie philolo- gischer Editionen und Studienausgaben jiddischer Literatur. Jiddisch, Englisch und Deutsch stehen als Publikationsspra- chen gleichberechtigt nebeneinander. Leket erscheint anlässlich des xv. Sym posiums für Jiddische Studien in Deutschland, ein im Jahre 1998 von Erika Timm und Marion Aptroot als für das in Deutschland noch junge Fach Jiddistik und dessen interdisziplinären אָ רשונג אויסגאַבעס און ייִדיש אויסגאַבעס און אָ רשונג Umfeld ins Leben gerufenes Forum. Die im Band versammelten 32 Essays zur jiddischen Literatur-, Sprach- und Kul- turwissenschaft von Autoren aus Europa, den usa, Kanada und Israel vermitteln ein Bild von der Lebendigkeit und Viel- falt jiddistischer Forschung heute. Yiddish & Research Editions ISBN 978-3-943460-09-4 Jiddistik Jiddistik & Forschung Edition 9 783943 460094 ִיידיש ַאויסגאבעס און ָ ארשונג Jiddistik Edition & Forschung Yiddish Editions & Research Herausgegeben von Marion Aptroot, Efrat Gal-Ed, Roland Gruschka und Simon Neuberg Band 1 לקט ִיידישע שטודיעס ַהנט Jiddistik heute Yiddish Studies Today Herausgegeben von Marion Aptroot, Efrat Gal-Ed, Roland Gruschka und Simon Neuberg Yidish : oysgabes un forshung Jiddistik : Edition & Forschung Yiddish : Editions & Research Herausgegeben von Marion Aptroot, Efrat Gal-Ed, Roland Gruschka und Simon Neuberg Band 1 Leket : yidishe shtudyes haynt Leket : Jiddistik heute Leket : Yiddish Studies Today Bibliografijische Information Der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deut- schen Nationalbibliografijie ; detaillierte bibliografijische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. © düsseldorf university press, Düsseldorf 2012 Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urhe- berrechtlich geschützt. -

Schiller's Egmont and the Beginnings of Weimar Classicism*

Steffan Davies Schiller’s Egmont and the Beginnings of Weimar Classicism* This essay examines Schiller’s stage version of Goethe’s Egmont, which was performed in Weimar in April 1796 and which Schiller described as “gewissermaasen Göthens und mein gemeinschaftliches Werk”. Beginning with his review of Egmont in 1788 the essay demonstrates some of the principles on which Schiller amended the text, and then shows that these match changes in Goethe’s own writing by the mid-1790s. On this basis it evalu- ates the correspondence between Goethe and Schiller, and other biographical texts, to reconsider the view that Goethe’s misgivings about the adaptation marked a low-point in their relationship. It argues that Schiller’s work on Egmont instead deserves to be seen as a constructive experience in the development of the Weimar alliance. I. Schiller had spent three weeks in Weimar watching performances by Iffland and his visiting theatre company when he wrote a letter to Körner on 10 April 1796. His aim: to persuade Körner to join him for Iffland’s last performance, Goethe’s Egmont, which he had adapted for the stage. He sounds happy with his stay and with his work, describing the new Egmont as “gewissermaasen Göthens und mein gemeinschaftliches Werk” (NA 28. 210–211). Goethe, Schiller and Iffland – surely Körner would not want to miss experiencing such a combination of talents.1 * Schiller’s texts are quoted from Schillers Werke. Nationalausgabe. Ed. by Julius Petersen, Gerhard Fricke et al. Weimar: Hermann Böhlaus Nachf. 1943ff. Quotations are identified by NA with volume and page numbers. -

The Enlightenment Novel As Artifact

4 The Enlightenment Novel as Artifact J. H. Campe’s Robinson der Jüngere and C. M. Wieland’s Der goldne Spiegel How did German authors respond to the widespread perception of literature as a luxury good and reading as a form of consumption? Or, to use a more mod- ern idiom, how did German literature around 1800 respond to its own commodi- fi cation? The question is not new to scholars of German culture; nonetheless, the topic deserves further attention. 1 The idea of literature as a potentially pernicious form of luxury posed a serious challenge to writers in this period, a challenge that not only infl uenced conceptions of the book as artifact and of the impact of read- ing, but also shaped the narrative structure and rhetorical features of the literary works themselves. Previous analyses of the subject have tended to be either too broad or too restric- tive in their approach. Too broad in the sense that they have addressed general con- cerns, such as the rise of the middle class or the dehumanizing impact of modern capitalism rather than the way in which evolving, complex, and often confl icted 1. Daniel Purdy addresses the topic in his insightful treatment of neoclassicism (Weimar classi- cism), and it has also been dealt with in some recent and not so recent genealogies of aesthetic auton- omy and of what is known in German as Trivialliteratur. See Purdy, The Tyranny of Elegance: Consumer Capitalism in the Era of Goethe (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998), esp. 28–34; Martha Woodmansee, The Author, Art, and the Market: Rereading the History of Aesthetics (New York: Colum- bia University Press, 1994); and Jochen Schulte-Sasse, Der Kritik der Trivialliteratur seit der Aufklärung (Munich: Wilhelm Fink Verlag, 1971). -

Article “On the Mysteries of the Egyptians” (“Ueber Die Mysterien Der Aegyptier”) of 1784

© Bildarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz Johann Christoph Friedrich von Schiller, oil painting by Gerhard von Kügelgen, 1808–1809. Original: Freies Deutsches Hochstift, Frankfurt am Main. Schiller’s philosophy of moral education, an integral part of Weimar Classicism and devel- oped most fully in On the Aesthetic Education of Man in a Series of Letters (1795), is a productive eighteenth-century lens through which to view the ideas of moral progression found in The Magic Flute. Photograph by Lutz Braun. From Arcadia to Elysium in The Magic Flute and Weimar Classicism The Plan of Salvation and Eighteenth-Century Views of Moral Progression John B. Fowles The painful sighs are now past. Elysium’s joyful banquets Drown the slightest moan— Elysium’s life is Eternal rapture, eternal flight; Through laughing meadows a brook pipes its tune. Here faithful couples embrace each other, Kiss on the velvet green sward As the soothing west wind caresses them; Here love is crowned, Safe from death’s merciless blow It celebrates an eternal wedding feast. ₁ —Friedrich Schiller resumably, many people gloss over the aphorism that life is a journey— ₂ Pindeed, for Latter-day Saints, an “eternal journey” —as cliché. But this aphorism encapsulates profound theological, philosophical, moral, and even teleological implications that should indeed interest most people. The journey metaphor connotes progress and ascension, indicating beginning, purpose, and end to mortal existence. True, moving linearly from point A to point B—metaphorically ascending a ladder or climbing a steep moun- ₃ tain —fittingly illustrates the progress inherent in this eternal journey. But a cyclical understanding of this progression—spiraling upward from one state of being to another—also captures and perhaps even enriches the sense of mankind’s journey. -

“Im Kampf, Penthesilea Und Achill”. Pentesilea Y Aquiles: ¿Kleist Y Goethe?

“Im Kampf, Penthesilea und Achill”. Pentesilea y Aquiles: ¿Kleist y Goethe? Raúl TORRES MARTÍNEZ Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Este pequeño ensayo pretende revisar la vieja teoría del agón literario entre Heinrich von Kleist y Johann Wolfgang Goethe, aportando algo novedoso desde el punto de vista de la Grecística, y tomando, a modo de ilustración, elementos de la tragedia Pentesilea del escritor prusiano. La Antigüedad, la androginia y el agón mismo son puntos de partida desde los que podemos sacar provecho al aproximarnos al llamado Goethezeit. PALABRAS CLAVE: mitología griega, homoerotismo, Kleist, Pentesilea, Goethezeit, Goethe. This little essay aims at elaborating on the old theory of the literary agon between the german poets Heinrich von Kleist and Johann. Wolfgang Goethe. It provides some Greek elements until almost unnoticed to modern scholars, taking, as a sort of example, the tragedy Penthesilea of the prusian author. Greek antiquity, an- drogyny and the agon itself, are points of view from wich we may win new perspectives in approaching the so-called Goethezeit. KEYWORDS: Greek mythology, homoerotism, Kleist, Penthesilea, Goethezeit, Goethe. I Wilhelm von Humboldt, en un locus classicus (Humboldt, 2002: 609) hoy, sin embar- go, casi desconocido, “Acerca de la diferencia entre los sexos y su influjo sobre la naturaleza orgánica”, publicado en 1795 en Die Horen, la revista de Schiller, dice a la letra: “La naturaleza no sería naturaleza sin él [sc. el concepto de sexo], su meca- nismo se detendría y, tanto la atracción (“Zug”) que une a todos los seres, como la lucha que todos necesitan para armarse con la energía que a cada uno le es propia, desaparecerían, si en lugar de la diferencia de sexos tuviéramos una igualdad aburrida y floja” (Humboldt, 2002: 268). -

Die Hermannsschlacht

WWWW ^W^H^I INTRODUCTION AND NOTES TO KLEIST'S DIE HERMANNSSCHLACHT BY FRANCES EMELINE GILKERSON, A. B. '03. THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 1904 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS THIS IS TO CERTIFY THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Q^/iß^Mt St^uljIcI^ bZL^/teAsC^ ENTITLED IS APPROVED BY ME AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF HEAD OF DEPARTMENT OF 4 PREFACE. This volume has been prepared to meet the demand for an .edition of Kleist' s "Die Hermannsschlacht" with English Introduction and Notes. It is designed for advanced classes, capable of reading and understanding the play as literature. As a fairly good reading knowledge of the language is taken forgranted, few grammatical passages are explained. The Introduction is intended to give such historical, biographi- cal and critical material as will prepare the student for the most profitable and appreciative reading of the play. It has been said that Kleist is one of those poets whose work cannot be fully under- stood without a knowledge of their lives. But this is perhaps less true of "Die Hermannsschlacht" than of some of Kleist' s other works. For an intelligent understanding of this drama an intimate knowledge of the condition of Germany in the early part of the Nineteenth Century is even more essential than a knowledge of the poet's life. The Notes contain such suggestions regarding classical, geo- graphical, and vague allusions as are deemed necessary or advisable for understanding this great historical drama. -

General Index

Cambridge University Press 0521780098 - The Cambridge Companion to Twentieth-Century Opera Edited by Mervyn Cooke Index More information General index Abbate, Carolyn 282 Bach, Johann Sebastian 105 Adam, Fra Salimbene de 36 Bachelet, Alfred 137 Adami, Giuseppe 36 Baden-Baden 133 Adamo, Mark 204 Bahr, Herrmann 150 Adams, John 55, 204, 246, 260–4, 289–90, Baird, Tadeusz 176 318, 330 Bala´zs, Be´la 67–8, 271 Ade`s, Thomas 228 ballad opera 107 Adlington, Robert 218, 219 Baragwanath, Nicholas 102 Adorno, Theodor 20, 80, 86, 90, 95, 105, 114, Barbaja, Domenico 308 122, 163, 231, 248, 269, 281 Barber, Samuel 57, 206, 331 Aeschylus 22, 52, 163 Barlach, Ernst 159 Albeniz, Isaac 127 Barry, Gerald 285 Aldeburgh Festival 213, 218 Barto´k, Be´la 67–72, 74, 168 Alfano, Franco 34, 139 The Wooden Prince 68 alienation technique: see Verfremdungse¤ekt Baudelaire, Charles 62, 64 Anderson, Laurie 207 Baylis, Lilian 326 Anderson, Marian 310 Bayreuth 14, 18, 21, 49, 61–2, 63, 125, 140, 212, Andriessen, Louis 233, 234–5 312, 316, 335, 337, 338 Matthew Passion 234 Bazin, Andre´ 271 Orpheus 234 Beaumarchais, Pierre-Augustin Angerer, Paul 285 Caron de 134 Annesley, Charles 322 Nozze di Figaro, Le 134 Ansermet, Ernest 80 Beck, Julian 244 Antheil, George 202–3 Beckett, Samuel 144 ‘anti-opera’ 182–6, 195, 241, 255, 257 Krapp’s Last Tape 144 Antoine, Andre´ 81 Play 245 Apollinaire, Guillaume 113, 141 Beeson, Jack 204, 206 Appia, Adolphe 22, 62, 336 Beethoven, Ludwig van 87, 96 Aquila, Serafino dall’ 41 Eroica Symphony 178 Aragon, Louis 250 Beineix, Jean-Jacques 282 Argento, Dominick 204, 207 Bekker, Paul 109 Aristotle 226 Bel Geddes, Norman 202 Arnold, Malcolm 285 Belcari, Feo 42 Artaud, Antonin 246, 251, 255 Bellini, Vincenzo 27–8, 107 Ashby, Arved 96 Benco, Silvio 33–4 Astaire, Adele 296, 299 Benda, Georg 90 Astaire, Fred 296 Benelli, Sem 35, 36 Astruc, Gabriel 125 Benjamin, Arthur 285 Auden, W. -

9781469658254 WEB.Pdf

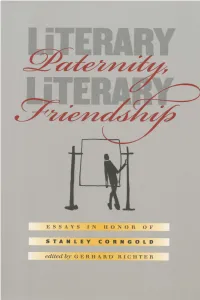

Literary Paternity, Literary Friendship From 1949 to 2004, UNC Press and the UNC Department of Germanic & Slavic Languages and Literatures published the UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures series. Monographs, anthologies, and critical editions in the series covered an array of topics including medieval and modern literature, theater, linguistics, philology, onomastics, and the history of ideas. Through the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, books in the series have been reissued in new paperback and open access digital editions. For a complete list of books visit www.uncpress.org. Literary Paternity, Literary Friendship Essays in Honor of Stanley Corngold edited by gerhard richter UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures Number 125 Copyright © 2002 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons cc by-nc-nd license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons. org/licenses. Suggested citation: Richter, Gerhard. Literary Paternity, Liter- ary Friendship: Essays in Honor of Stanley Corngold. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.5149/9780807861417_Richter Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Richter, Gerhard, editor. Title: Literary paternity, literary friendship : essays in honor of Stanley Corngold / edited by Gerhard Richter. Other titles: University of North Carolina studies in the Germanic languages and literatures ; no. 125. Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [2002] Series: University of North Carolina studies in the Germanic languages and literatures | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: lccn 2001057825 | isbn 978-1-4696-5824-7 (pbk: alk. paper) | isbn 978-1-4696-5825-4 (ebook) Subjects: German literature — History and criticism. -

Selected Prose of Heinrich Von Kleist

Selected Prose of Heinrich Von Kleist 098195572X, 9780981955728, Heinrich von Kleist, Selected Prose of Heinrich Von Kleist, 2010, 283 pages, Archipelago Books, 2010, In this extraordinary and unpredictable cross-section of the work of one of the most influential free spirits of German letters, Peter Wortsman captures the breathlessness and power of Heinrich von Kleist’s transcendent prose. These tales, essays, and fragments move across inner landscapes, exploring the shaky bridges between reason and feeling and the frontiers between the human psyche and the divine. From the "The Earthquake in Chile," his damning invective against moral tyranny; to "Michael Kohlhaas," an exploration of the extreme price of justice; to "The Marquise of O . ," his twist on the mythic triumph of love story; to his essay "On the Gradual Formulation of Thoughts While Speaking," which tracks the movements of the unconscious decades before Freud; Kleist unrelentingly confronts the dangers of self-deception and the ultimate impossibility of existence ina world of absolutes. Wortsman’s illuminating afterword demystifies Kleist’s vexed history, explaining how the century after his death saw Kleist’s legacy transformed from that of a largely derided playwright into a literary giant who would inspire Thomas Mann and Franz Kafka. The concerns of Heinrich von Kleist are timeless. The mysteries in his fiction and visionary essays still breathe. file download musu.pdf 341 pages, Heinrich von Kleist, 1982, ISBN:0826402631, Plays Selected Prose of Heinrich Von Kleist -

Wissenschaftskolleg Zu Berlin Jahrbuch 1986/87

Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin Jahrbuch 1986/87 WISSENSCHAFTSKOLLEG -INSTITUTE FOR ADVANCED STUDY - ZU BERLIN JAHRBUCH 1986/87 NICOLAISCHE VERLAGSBUCHHANDLUNG © 1988 by Nicolaische Verlags- buchhandlung Beuermann GmbH, Berlin und Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin — Institute for Advanced Study — Alle Rechte, auch das der fotomechanischen Wiedergabe, vorbehalten Redaktion: Ingrid Rudolph Satz: MEDIA trend, Berlin Druck: Druckerei Gerike, Berlin Buchbinder: Luderitz & Bauer, Berlin Printed in Germany 1988 ISBN 3-87584-236-7 5 Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorbemerkung des Herausgebers 11 Arbeitsberichte MOHAMMED ARKOUN 17 PETER AX 20 DAVID R. AXELRAD 24 PETER BOERNER 27 ELIESER L. EDELSTEIN 30 GEORG ELWERT 33 JANE FULCHER 38 MAURICE GARDEN 39 ALDO G. GARGANI 41 JACOB GOLDBERG 43 RAINER GRUENTER 48 ROLF HOCHHUTH 49 6 GERTRUD HOHLER 51 JOHN HOPE MASON 55 LOTHAR JAENICKE 58 RUTH KATZ 62 GIULIANA LANATA 64 HERBERT MEHRTENS 67 KLAUS MOLLENHAUER 73 AUGUST NITSCHKE 81 DIETER NORR 83 MICHAEL OPPITZ 84 ADRIANA ORTIZ-ORTEGA 89 JOSEF PALDUS 93 ULRICH POTHAST 98 PETER HANNS REILL 102 7 RICHARD RORTY 105 BERND ROTHERS 108 PETER SCHEIBERT 111 YONATHAN SHAPIRO 114 VERENA STOLCKE 117 HENRY A. TURNER 122 BRIAN VICKERS 124 GYÖRGY WALKO 130 R. J. ZWI WERBLOWSKI 134 O. K. WERCKMEISTER 73 8 Seminarberichte Constitutive Laws and Microstructure Seminar veranstaltet von DAVID R. AXELRAD und WOLFGANG MUSCHIK 23.-24. Februar 1987 139 Der Wandel am Anfang des 20. Jahrhunderts. Parallele Veränderungen in Wissenschaft, Kunst, Recht und in bevorzugten Bewegungsweisen. Verschiedene Erklärungsmodelle. Seminar veranstaltet von HERBERT MEHRTENS und AUGUST NITSCHKE 11.-12. März 1987 140 Unternehmer und Regime im Dritten Reich Seminar veranstaltet von HENRY A. TURNER 19.-21. März 1987 145 Die deutsche Kunst unter der nationalsozialistischen Regierung als Gegenstand der kunstgeschichtlichen Forschung Seminar veranstaltet von O.K. -

Everybody's Talking: Non-Verbal Communication in “Über Die

AT A LOSS FOR WORDS: NONVERBAL COMMUNICATION IN KLEIST‟S “ÜBER DIE ALLMÄHLICHE VERFERTIGUNG DER GEDANKEN BEIM REDEN,” “MICHAEL KOHLHAAS,“ AND “DER FINDLING“ Matthew Feminella A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures. Chapel Hill 2010 Approved by: Dr. Clayton Koelb (Advisor) Dr. Eric Downing Dr. Jonathan Hess ABSTRACT Matthew Feminella: At a Loss for Words: Nonverbal Communication in Kleist‟s “Über die allmähliche Verfertigung der Gedanken beim Reden,” “Michael Kohlhaas,“ and “Der Findling“ (Under the direction of Dr. Clayton Koelb) This thesis examines instances of nonverbal communication in three works of Heinrich von Kleist. Once viewed outside the context of authentic communication, nonverbal signs expose structures within his texts. These structures reveal overlooked conflicts and character dynamics. The first chapter explores the essay “Über die allmähliche Verfertigung der Gedanken beim Reden,” and demonstrates that Kleist‟s model of successful speech acts as an implicit dialogue and consists of nonverbal cues performed the speech recipient. The second chapter extends this analysis to “Michael Kohlhaas,” whose protagonist is gradually exiled into a nonverbal condition. The third chapter examines the nonverbal elements in “Der Findling,” particularly glancing, and claims that through nonverbal acts characters previously thought of as passive play an additional active role. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction……………………………………………………………………….………..1 II. Don‟t Speak When Spoken to?: Kleist‟s Nonverbal Dialogue in “Über die allmähliche Verfertigung der Gedanken beim Reden”............................................................................9 III. Lieber ein Hund sein: Subjugation and the Nonverbal in “Michael Kohlhaas”................26 IV.