Chiricahua National Monument Historic Designed Landscape Historic Name

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FACT SHEET OVERVIEW Lower Cliff Dwelling Construction Sequence

southwestlearning.org TONTO Lower Cliff Dwelling FACTOVERVIEW SHEET Construction Sequence ARCHIVES SERVICE PARK NATIONAL Tonto National Monument, established in 1907, protects several cliff dwelling sites and numerous smaller archeo- logical sites scattered throughout the highlands and allu- vial plains within the Tonto Basin, Arizona. The Lower Cliff Dwelling is one of two large sites accessible to the public, and is the primary site visited in the Monument throughout the year. Background The Lower Cliff Dwelling consists of an approximately 20- room masonry and adobe village built within a natural al- cove above a side drainage of the Salt River called Cholla Canyon and overlooking Cave Canyon, where there is now an active spring. The site itself has been known since at The Lower Cliff Dwelling at Tonto National Monument, ca. 1905. least the late 1800s, and unfortunately, was subject to exces- sive looting and associated damage long before becoming a lage was not built all at once, however, and instead started Monument in 1907 and later coming under the protection of with only one or two rooms, to which additional rooms the National Park Service (NPS) in 1933. However, histor- were added over a period of perhaps 30 years (Nordby et ic photographs, excavation and stabilization records (e.g., al. 2012). New rooms were built on bedrock, artificially Duffen 1937; Pierson 1952), and recent research provide leveled floors, and accumulated trash. While the rocks and some indication of when and how the Lower Cliff Dwelling clay for the adobe were readily available (Nordby et al. was constructed, and to some extent, by whom. -

Chiricahuas Present a Verdant, Forested Island in a Sea of Desert

Rising steeply from the dry grasslands of southeastern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico, the Chiricahuas present a verdant, forested island in a sea of desert. Many species of trees, shrubs, and flowering herbs clothe steep canyon walls. Shady glens, alive with birds, are sheltered by rows of strange massive spires, turrets, and battlements in this fascinating wonderland of rocks. Story of the rocks-What geological forces created these striking and peculiar pinnacles and balanced rocks? Geolo- gists explain that millions of years ago volcanic activity was extensive throughout this region. A series of explosive eruptions, alternating with periods of inactivity, covered the area with layers of white-hot volcanic ash that welded into rock. Because the eruptions varied in magnitude, the deposits were of different thicknesses. Finally, the eruptions ceased, followed by movements in the earth's crust which slowly lifted and tilted great rock masses to form mountains. The stresses responsible for the movements caused a definite pattern of cracks. Along the vertical cracks and planes of horizontal weakness, ero- sion by weathering and running water began its persistent work. Cracks were widened to form fissures; and fissures grew to breaches. At the same time, under-cutting slowly took place. Gradually the lava masses were cut by millions of ero- sional channels into blocks of myriad sizes and shapes, to be further sculptured by the elements. Shallow canyons became deeper and more rugged as time passed. Weathered rock formed soil, which collected in pockets; and plants thus gained a foothold. Erosion is still going on slowly and persistently among the great pillared cliffs of the monument. -

The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1

Contents Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances .......... 2 February 7–March 20 Vivien Leigh 100th ......................................... 4 30th Anniversary! 60th Anniversary! Burt Lancaster, Part 1 ...................................... 5 In time for Valentine's Day, and continuing into March, 70mm Print! JOURNEY TO ITALY [Viaggio In Italia] Play Ball! Hollywood and the AFI Silver offers a selection of great movie romances from STARMAN Fri, Feb 21, 7:15; Sat, Feb 22, 1:00; Wed, Feb 26, 9:15 across the decades, from 1930s screwball comedy to Fri, Mar 7, 9:45; Wed, Mar 12, 9:15 British couple Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders see their American Pastime ........................................... 8 the quirky rom-coms of today. This year’s lineup is bigger Jeff Bridges earned a Best Actor Oscar nomination for his portrayal of an Courtesy of RKO Pictures strained marriage come undone on a trip to Naples to dispose Action! The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1 .......... 10 than ever, including a trio of screwball comedies from alien from outer space who adopts the human form of Karen Allen’s recently of Sanders’ deceased uncle’s estate. But after threatening each Courtesy of Hollywood Pictures the magical movie year of 1939, celebrating their 75th Raoul Peck Retrospective ............................... 12 deceased husband in this beguiling, romantic sci-fi from genre innovator John other with divorce and separating for most of the trip, the two anniversaries this year. Carpenter. His starship shot down by U.S. air defenses over Wisconsin, are surprised to find their union rekindled and their spirits moved Festival of New Spanish Cinema .................... -

Tonto National Monument News Release

National Park Service Tonto National Monument U.S. Department of the Interior 26260 N. AZ Hwy. 188, Lot 2 Roosevelt, AZ 85545 928-467-2241 phone www.nps.gov/tont Tonto National Monument News Release Release date: Immediate Contact: Hilary Clark Phone number: (928) 467-2241 Email: [email protected] Date: April 28, 2017 Tourism to Tonto National Monument Creates 3, 155,800 in Economic Benefits Report shows visitor spending supports 33 jobs in local economy Roosevelt, AZ – A new National Park Service (NPS) report shows that in 2016, 38,048 visitors to Tonto National Monument spent $2, 224,600 in communities near the park. This visitor spending supported 33 jobs in the local area and had a cumulative benefit to the local economy of $3,155,800. “Tonto National Monument welcomes our local visitors and others from around the world,” said Superintendent Duane Hubbard. “We are delighted to share the story of Salado cliff dwellings and prehistoric artifacts that have been preserved for over 700 years. National park tourism is a significant driver in the national economy, returning more than $10 for every $1 invested in the National Park Service, and it’s a big factor in the Gila County economy as well. We appreciate the partnership and support of our neighbors and are glad to be able to give back by helping to sustain local communities.” The peer-reviewed visitor spending analysis was conducted by economists Catherine Cullinane Thomas of the U.S. Geological Survey and Lynne Koontz of the National Park Service. The report shows $18.4 billion of direct spending by 331 million park visitors in communities within 60 miles of a national park. -

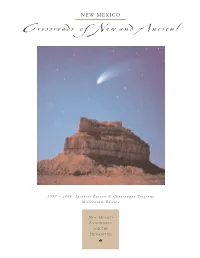

Crossroads of Newand Ancient

NEW MEXICO Crossroads of NewandAncient 1999 – 2000 Speakers Bureau & Chautauqua Programs Millennium Edition N EW M EXICO E NDOWMENT FOR THE H UMANITIES ABOUT THE COVER: AMATEUR PHOTOGRAPHER MARKO KECMAN of Aztec captures the crossroads of ancient and modern in New Mexico with this image of Comet Hale-Bopp over Fajada Butte in Chaco Culture National Historic Park. Kecman wanted to juxtapose the new comet with the butte that was an astronomical observatory in the years 900 – 1200 AD. Fajada (banded) Butte is home to the ancestral Puebloan sun shrine popularly known as “The Sun Dagger” site. The butte is closed to visitors to protect its fragile cultural sites. The clear skies over the Southwest led to discovery of Hale-Bopp on July 22-23, 1995. Alan Hale saw the comet from his driveway in Cloudcroft, New Mexico, and Thomas Bopp saw the comet from the desert near Stanfield, Arizona at about the same time. Marko Kecman: 115 N. Mesa Verde Ave., Aztec, NM, 87410, 505-334-2523 Alan Hale: Southwest Institute for Space Research, 15 E. Spur Rd., Cloudcroft, NM 88317, 505-687-2075 1999-2000 NEW MEXICO ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES SPEAKERS BUREAU & CHAUTAUQUA PROGRAMS Welcome to the Millennium Edition of the New Mexico Endowment for the Humanities (NMEH) Resource Center Programming Guide. This 1999-2000 edition presents 52 New Mexicans who deliver fascinating programs on New Mexico, Southwest, national and international topics. Making their debuts on the state stage are 16 new “living history” Chautauqua characters, ranging from an 1840s mountain man to Martha Washington, from Governor Lew Wallace to Capitán Rafael Chacón, from Pat Garrett to Harry Houdini and Kit Carson to Mabel Dodge Luhan. -

Availability of Additional Water for Chiricahua National Monument Cochise County, Arizona

Availability of Additional Water for Chiricahua National Monument Cochise County, Arizona By PHILLIP W. JOHNSON HYDROLOGY OF THE PUBLIC DOMAIN GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1475-H Prepared in cooperation with the National Park Service UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1962 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D.C. CONTENTS Pagre Abstract________________________________________________________ 209 Introduction. _____________________________________________________ 209 Geology..._______________________________________________ 211 Water resources___________________________________________________ 211 Surface flow__________________________________________________ 212 Springs and seeps____________________________________________ 212 Wells,_____________________________________________________ 213 Conclusions and suggestions ________________________________________ 214 Impoundment of surface flow __________________________________ 214 Development of springs and seeps.______________________________ 214 Deep test well_______________________________________________ 215 Test drilling in the alluvium._ _________________________________ 215 Selected references.._______________________________________________ 216 ILLUSTRATIONS Pa&e PLATE 17. Map of Chiricahua National Monument showing geology, wells, springs, seeps, and culture.________________ In pocket FIGURE -

Coronado National Forest Draft Land and Resource Management Plan I Contents

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Coronado National Forest Southwestern Region Draft Land and Resource MB-R3-05-7 October 2013 Management Plan Cochise, Graham, Pima, Pinal, and Santa Cruz Counties, Arizona, and Hidalgo County, New Mexico The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TTY). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Front cover photos (clockwise from upper left): Meadow Valley in the Huachuca Ecosystem Management Area; saguaros in the Galiuro Mountains; deer herd; aspen on Mt. Lemmon; Riggs Lake; Dragoon Mountains; Santa Rita Mountains “sky island”; San Rafael grasslands; historic building in Cave Creek Canyon; golden columbine flowers; and camping at Rose Canyon Campground. Printed on recycled paper • October 2013 Draft Land and Resource Management Plan Coronado National Forest Cochise, Graham, Pima, Pinal, and Santa Cruz Counties, Arizona Hidalgo County, New Mexico Responsible Official: Regional Forester Southwestern Region 333 Broadway Boulevard, SE Albuquerque, NM 87102 (505) 842-3292 For Information Contact: Forest Planner Coronado National Forest 300 West Congress, FB 42 Tucson, AZ 85701 (520) 388-8300 TTY 711 [email protected] Contents Chapter 1. -

Dos Cabezas Mountains Proposed LWC Is Affected Primarily by the Forces of Nature and Appears Natural to the Average Visitor

DOS CABEZAS MOUNTAINS LANDS WITH WILDERNESS CHARACTERISTICS PUBLIC LANDS CONTIGUOUS TO THE BLM’S DOS CABEZAS MOUNTAINS WILDERNESS IN THE NORTHERN CHIRICAHUA MOUNTAINS, ARIZONA A proposal report to the Bureau of Land Management, Safford Field Office, Arizona APRIL, 2016 Prepared by: Joseph M. Trudeau, Amber R. Fields, & Shannon Maitland Dos Cabezas Mountains Wilderness Contiguous Proposed LWC TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE: This Proposal was developed according to BLM Manual 6310 page 3 METHODS: The research approach to developing this citizens’ proposal page 5 Section 1: Overview of the Proposed Lands with Wilderness Characteristics Unit Introduction: Overview map showing unit location and boundaries page 8 • provides a brief description and labels for the units’ boundary Previous Wilderness Inventories: Map of former WSA’s or inventory unit’s page 9 • provides comparison between this and past wilderness inventories, and highlights new information Section 2: Documentation of Wilderness Characteristics The proposed LWC meets the minimum size criteria for roadless lands page 11 The proposed LWC is affected primarily by the forces of nature page 12 The proposed LWC provides outstanding opportunities for solitude and/or primitive and unconfined recreation page 16 A Sky Island Adventure: an essay and photographs by Steve Till page 20 MAP: Hiking Routes in the Dos Cabezas Mountains discussed in this report page 22 The proposed LWC has supplemental values that enhance the wilderness experience & deserve protection page 23 Conclusion: The proposed -

Ohio Archaeologist Volume 43 No

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGIST VOLUME 43 NO. 2 SPRING 1993 Published by THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF OHIO The Archaeological Society of Ohio MEMBERSHIP AND DUES Annual dues to the Archaeological Society of Ohio are payable on the first TERM of January as follows: Regular membership $17.50; husband and wife EXPIRES A.S.O. OFFICERS (one copy of publication) $18.50; Life membership $300.00. Subscription to the Ohio Archaeologist, published quarterly, is included in the member 1994 President Larry L. Morris, 901 Evening Star Avenue SE, East ship dues. The Archaeological Society of Ohio is an incorporated non Canton, OH 44730, (216) 488-1640 profit organization. 1994 Vice President Stephen J. Parker, 1859 Frank Drive, Lancaster, OH 43130, (614)653-6642 BACK ISSUES 1994 Exec. Sect. Donald A. Casto, 138 Ann Court, Lancaster, OH Publications and back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist: Ohio Flint Types, by Robert N. Converse $10.00 add $1.50 P-H 43130,(614)653-9477 Ohio Stone Tools, by Robert N. Converse $ 8.00 add $1.50 P-H 1994 Recording Sect. Nancy E. Morris, 901 Evening Star Avenue Ohio Slate Types, by Robert N. Converse $15.00 add $1.50 P-H SE. East Canton, OH 44730, (216) 488-1640 The Glacial Kame Indians, by Robert N. Converse .$20.00 add $1.50 P-H 1994 Treasurer Don F. Potter, 1391 Hootman Drive, Reynoldsburg, 1980's & 1990's $ 6.00 add $1.50 P-H OH 43068, (614)861-0673 1970's $ 8.00 add $1.50 P-H 1998 Editor Robert N. Converse, 199 Converse Dr., Plain City, OH 1960's $10.00 add $1.50 P-H 43064,(614)873-5471 Back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist printed prior to 1964 are gener ally out of print but copies are available from time to time. -

Bandelier National Monument Executive Summary & Final Report

NPS Greening Charrette -- Bandelier National Monument Executive Summary & Final Report This report is a summary of the NPS Bandelier Greening Charrette Conducted in Santa Fe, New Mexico on April 8-10, 2003 Funding and coordination provided by: U.S Environmental Protection Agency National Park Service Bandelier National Monument Final Report prepared by: Joel A. Todd and Gail A. Lindsey, FAIA 1 Bandelier National Monument Greening Charrette April 8-10, 2003 Santa Fe, New Mexico Executive Summary Bandelier National Monument is located northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico. It contains cliff dwellings and other structures built by Puebloan ancestors as well as more recent buildings constructed by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s. In addition, there are almost 33,000 acres of wilderness, served by only three miles of public road and 70 miles of trails. The park has already taken steps to “green” its operations, but important issues remain. These include crowded parking lots and lines of cars waiting to enter the park, maintenance and updating of the historic CCC buildings including the Visitor Center, renovation of the snack bar and renegotiation of the concessions contract, and construction of a new maintenance facility at the current “boneyard.” This workshop and charrette was the third in a series co- sponsored by the National Park Service and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Participants included the Bandelier Superintendent and staff as well as personnel from other national parks, state parks, and experts from around the country. The day before the event, there was a tour of the park, designed to introduce participants to issues at Bandelier. -

The Common Field Mississippian Site(23SG100), As Uncovered by the 1979 Mississippi River Flood Richard E

The Common Field Mississippian Site(23SG100), as Uncovered by the 1979 Mississippi River Flood Richard E. Martens Two of the pictures I took during an early visit to the he Common Field site occurs near the bluffs in the site are shown in Figure 1. The first shows Mound A, the TMississippi River floodplain 3 km south of St. Gen- largest of the six then-existing mounds. The nose of my evieve and approximately 90 km south of St. Louis. It is brand-new 1980 Volkswagen parked on the farm road is a large Mississippian-period site that once had as many as in the lower right corner of the picture. The second photo eight mounds (Bushnell 1914:666). It was long considered shows the outline of a burned house structure typical of to be an unoccupied civic-ceremonial center because very many evident across the site. Although it has been noted few surface artifacts were found. This all changed due that many people visited the site shortly after the flood, I to a flood in December 1979, when the Mississippi River did not meet anyone during several visits in 1980 and 1981. swept across the Common Field site. The resulting erosion I subsequently learned that Dr. Michael O’Brien led removed up to 40 cm of topsoil, exposing: a group of University of Missouri (MU) personnel in a [a] tremendous quantity of archaeological material limited survey and fieldwork activity in the spring of 1980. including ceramic plates, pots and other vessels, articu- The first phase entailed aerial photography (black-and- lated human burials, well defined structural remains white and false-color infrared) of the site. -

Castle Clinton Foundation Document

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Castle Clinton National Monument New York September 2018 Foundation Document Robert F Whitehall St Wagner Jr Beaver St Battery P t Park l S am illi Castle Clinton S W National Monument Stone St Bridge St Pearl St State St Water St Broad St Battery Upper Bay South St §¨¦478 Battery Whitehall Maritime Terminal Building Manhattan North 0 250 500 Á Feet Castle Clinton National Monument Contents Mission of the National Park Service 1 Introduction 2 Part 1: Core Components 3 Brief Description of the Park 3 Park Purpose 4 Park Significance 5 Fundamental Resources and Values 6 Related Resources 7 Interpretive Themes 8 Part 2: Dynamic Components 9 Special Mandates and Administrative Commitments 9 Assessment of Planning and Data Needs 9 Analysis of Fundamental Resources and Values 9 Identification of Key Issues and Associated Planning and Data Needs 15 Planning and Data Needs 16 Part 3: Contributors 19 Castle Clinton National Monument 19 NPS Northeast Region 19 Other NPS Staff 19 Partners 19 Appendixes 20 Appendix A: Enabling Legislation and Legislative Acts for Castle Clinton National Monument 20 Appendix B: Inventory of Administrative Commitments 22 Foundation Document Castle Clinton National Monument Mission of the National Park Service The National Park Service (NPS) preserves unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and values of the national park system for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations. The National Park Service cooperates with partners to extend the benefits of natural and cultural resource conservation and outdoor recreation throughout this country and the world.