Transience and Durability in Japanese Urban Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trip to Japan

Trip to Japan Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Trip to Japan Our trip to Japan from Tokyo to Kyoto Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 1 - Arrival to Tokyo Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 1 - Arrival to Tokyo 1. Tokyo Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 2 - Tokyo Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 2 - Tokyo 1. Tokyo Tokyo, Japan WIKIPEDIA Tokyo, officially Tokyo Metropolis, one of the 47 prefectures of Japan, has served as the Japanese capital since 1869. As of 2014 the Greater Tokyo Area ranked as the most populous metropolitan area in the world. The urban area houses the seat of the Emperor of Japan, of the Japanese government and more.. Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 3 - Tokyo Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 4 - Nikko Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 4 - Nikko 1. Nikko Nikko, Tochigi, Japan WIKIPEDIA Nikko may refer to: Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 5 - Nikko Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 5 - Nikko 1. Nikko Nikko, Tochigi, Japan WIKIPEDIA Nikko may refer to: 2. Nikko National Park Yumoto, Nikko, Tochigi Prefecture 321-1662, Japan Rating: 4 WIKIPEDIA Nikkō Naonal Park is a naonal park in the Kantō region, on the main island of Honshū in Japan. The park spreads over four prefectures: Tochigi, Gunma, Fukushima, and Niigata, and was established in 1934. Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 6 - Nikko to Tokyo Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 6 - Nikko to Tokyo 1. -

Conceito De Mínimo Na Arquitetura: Proposta Para a Quinta Do Canavial (Covilhã)

UNIVERSIDADE DA BEIRA INTERIOR Engenharia Conceito de Mínimo na Arquitetura: proposta para a Quinta do Canavial (Covilhã) Ana Catarina Novais Gavina Dissertação para obtenção do Grau de Mestre em Arquitetura (ciclo de estudos integrado) Orientador: Prof. Doutor Ana Maria Tavares Ferreira Martins Co-orientador: Prof. Doutor Miguel Costa santos Nepomoceno Covilhã, Abril de 2016 ii Dedicatória Aos meus pais e irmã. iii iv Agradecimentos A todos aqueles que me acompanharam neste percurso, família, amigos, orientadores mas em especial aos meus pais e irmã que sem eles era impossível chegar até ao fim. v vi Resumo A presente dissertação irá abordar como tema fulcral a Habitação tendo de conceito principal o mínimo nas suas múltiplas vertentes. Desta forma, intrínsecos a esta temática, estão conceitos como o Minimalismo, a Flexibilidade e Funcionalidade. Apesar do Minimalismo ter tido as suas origens nas Artes Plásticas, em meados do séc. XX, já anteriores movimentos arquitétónicos tinham revelado resultados concordantes com os do Minimalismo (enquanto corrente estilística), como poderemos analisar através de exemplos escolhidos a nível do património histórico e do património contemporâneo da cela mínima e da habitação mínima, na Parte I. Respetivamente, o primeiro refere-se às celas monásticas e o segundo é relativo ao habitar mínimo tipicamente japonês, analisando pormenorizadamente os seus componentes e formas de habitar. Conclui-se a Parte I com um estudo da flexibilidade e multifuncionalidade de uma habitação, anunciando a filosofia “a forma segue a função”. Seguidamente, a Parte II, é exclusivamente dedicada à proposta do protótipo da habitação minimalista. Analisa-se primeiramente o terreno em questão, avaliando as suas considerações juntamente com as condicionantes da família do cliente. -

Hankyu Hanshin Holdings Securities Code: 9042 ANNUAL REPORT

Hankyu Hanshin Holdings Securities code: 9042 ANNUAL REPORT Hankyu Hanshin Holdings, Inc. ANNUAL REPORT 2016 Hankyu Inc. ANNUAL Hanshin Holdings, 2016 Growingthe Ground from Up ANNUAL REPORT 2016 Contents Key Facts Financial Section and Corporate Data 1 Group Management Philosophy 73 Consolidated Six-Year Summary 3 Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) 74 Consolidated Financial Review 4 At a Glance 77 Business Risks 6 Location of Our Business Base 78 Consolidated Balance Sheets 8 Business Environment 80 Consolidated Statements of Income / 10 Performance Highlights (Consolidated) Consolidated Statements of Comprehensive Income 14 ESG Highlights 81 Consolidated Statements of Changes in Net Assets 83 Consolidated Statements of Cash Flows 84 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements Business Policies and Strategies 108 Major Rental Properties / Major Sales Properties 16 To Our Stakeholders 109 Major Group Companies 24 Special Feature: Anticipating Change, 110 Group History Pursuing Growth Opportunities 111 Investor Information 29 Providing Services that Add Value to Areas 32 Capitalising on Opportunities through Overseas Businesses 36 CSR and Value Enhancement in Line-Side Areas Search Index Group Overview 1–15, 38–39, 108–111 Core Businesses: Overview and Outlook 2016 Financial and Business Performances 38 Core Business Highlights 10–13, 17–19, 73–76 40 Urban Transportation Forecasts for Fiscal 2017 Onward 44 Real Estate Group: 22 Urban Transportation: 41 48 Entertainment and Communications Real Estate: 45 50 Travel Entertainment and -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Transience and durability in Japanese urban space ROBINSON, WILFRED,IAIN,THOMAS How to cite: ROBINSON, WILFRED,IAIN,THOMAS (2010) Transience and durability in Japanese urban space, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/405/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Iain Robinson Transience and durability in Japanese urban space ABSTRACT The thesis addresses the research question “What is transient and what endures within Japanese urban space” by taking the material constructed form of one Japanese city as a primary text and object of analysis. Chiba-shi is a port and administrative centre in southern Kanto, the largest city in the eastern part of the Tokyo Metropolitan Region and located about forty kilometres from downtown Tokyo. The study privileges the role of process as a theoretical basis for exploring the dynamics of the production and transformation of urban space. -

Official Guide T2 All En.Pdf

2020 , 1 December 2020 FLOOR GUIDE ENGLISH December Narita International Airport Terminal2 Narita Airport is working in conjunction with organizations such as Japan’s Ministry of Narita International Airport FLOOR GUIDE, Planned and Published by Narita International Airport Corporation (NAA), Published Planned andPublished by Narita International FLOOR GUIDE, Airport Narita International Justice and Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare to combat the spread of COVID-19. Due to the spread of the virus, business hours may have changed at some terminal facilities and stores. For the latest information, please consult the Narita International Airport Official Website. Narita International Airport Ofcial Website 英語 CONTENTS INFORMATION & SERVICES Lost Item Inquiries/infotouch Interactive Digital Displays NariNAVI/Lounges …………………………………………………………4 Flight Information/ Terminals and Airlines ……………………………………… 5 Internet Services ……………………………………………………………5 General Information ………………………………………………………5 FLOOR MAP Terminal 2 Services Map ……………………………………… 6–7 B1F Railways (Airport Terminal2 Station) ……………………………………………… 8–9 1F International Arrival Lobby …………………………………………… 10–11 2F Parking Lot Accessway ……………………………………………… 12–13 3F International Departure Lobby (Check-in Counter) ………………… 14–15 4F Restaurants and Shops/Observation Deck ……………………… 16–17 3F International Departure Lobby (Boarding Gate)/ Duty Free and Shopping Area ……………………………………… 18–21 Domestic Flights …………………………………………………… 22–23 SHOPS AND FACILITIES Before Passport Control … 24–29 After Domestic Check-in -

OBJETIVOS: Reduzir a Quantidade De Lixo Comum Em 50% . . . E Aumentar a Taxa De Reciclagem Para

OBJETIVOS: reduzir a quantidade de lixo comum em 50% . Edição Revisada Outubro de 2016 e aumentar a taxa de reciclagem para 33% ÍNDICE Parte 1 Rumo à redução do lixo e aumento da reciclagem 3 O que podemos fazer agora 3 Para reaproveitar os recursos, é necessário separar 3 Drenar a água, secar o lixo, fazer a compostagem 3 O novo sistema dos “Sacos da Dieta do Lixo” 4 Parte 2 Categorias de Lixo e Métodos de Processamento 6 11 Categorias de Lixo e 20 tipos de artigo 6 Lixo Queimável(Lixo Comum) 6 Lixo de Embalagens Plásticas 7 Papéis Recicláveis 9 Latas 10 Metais 10 Lixo a ser Triturado 11 Garrafas de Vidro 11 Lixo Tóxico 12 Garrafas PET 12 Lixo a ser Aterrado 13 Lixo de Grande Porte (77 artigos designados) 14 Roupas e artigos de tecido: locais de coleta 17 Estações de reciclagem 18 Parte 3 Lixo que a Prefeitura não recolhe 19 1. Lixo em grande quantidade ou de grandes dimensões 19 2. Pneus e Baterias 19 3. Descarte de eletrodomésticos regulado por lei 20 4. Computadores 21 5. Veículos de duas rodas 21 6. Extintores de Incêndio 22 7. Botijão de Gás Propano 22 8. Limpeza de Banheiros Químicos 23 Parte 4 Descarte ilegal de lixo e outras questões 24 1. Descarte ilegal de lixo 24 2. Incineração ao ar livre 24 3. Empresas privadas para coleta de lixo comum 25 ◆ Lista de materiais em ordem alfabética: como separar cada item 26 ◆ LIXO QUE NÃO DEVE SER JOGADO NO LOCAL DE COLETA DE SEU BAIRRO NEM LEVADO AO BIKA CENTER RUMO À REDUÇÃO DO LIXO E AUMENTO DA RECICLAGEM “Smart city”: cidade, pessoas e meio ambiente em harmonia ●O que podemos fazer agora O descarte de lixo é uma questão crucial para se pensar o meio ambiente global. -

Entrance Ceremony Held to Welcome Newest Students by JIU Times

Produced by × JIU TIMES Vol. 16 SPRING 2016 Entrance ceremony held to welcome newest students by JIU Times Josai International University (JIU) held an entrance ceremony for new students on April 2 at its Togane Campus in Chiba Prefecture. The university, which is celebrating the 25th year anniversary, welcomed 1,650 students to its eight faculties and graduate school, as well as its school of Japanese Language and Culture. Among freshmen, 330 were non-Japanese from 22 countries and regions in Asia, Europe and South America. The ceremony at the Sports Culture Center was attended by foreign dignitaries, including HRH Tuanku Syed Faizuddin Putra Ibni Tu- anku Syed Sirajuddin Jamalullail, the Crown Prince of Perlis, Malaysia; HRH Tuanku Haj- jah Lailatul Shahreen Akashah Binti Khalil, Right photo: The Crown Prince of Perlis, Malaysia, HRH Tuanku Syed Faizuddin Putra Ibni Tuanku Syed Sirajuddin Jamalullail, one of the guests at the JIU entrance ceremony, addresses new students at the Togane the Crown Princess of Perlis, Malaysia; former Campus in Chiba Prefecture on April 2; Left photo: The Crown Prince and Crown Princess of Perlis, Malaysia, HRH Tuanku Hajjah Lailatul Shahreen Akashah Binti Khalil, look on during the ceremony. Malaysian Minister of Tourism and Josai Cen- tre of ASEAN Studies Director Ng Yen Yen; Foundation that enabled five female students Bright future ahead for latest graduates of JIU Kamarudin Hussin, former vice chancellor of from the Southeast Asian country to study at Universiti Malaysia Perlis (UniMAP); and Zul the university from the 2016 academic year. by Terutada Tsunoda, Student Her Imperial Highness Princess Taka- Azhar Zahid Jamal, deputy vice chancellor of “Created by the mother of his royal high- Faculty of International Humanities mado attended the ceremony, offering a UniMAP. -

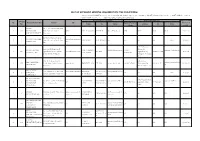

Summary of Family Membership and Gender by Club MBR0018 As of June, 2009

Summary of Family Membership and Gender by Club MBR0018 as of June, 2009 Club Fam. Unit Fam. Unit Club Ttl. Club Ttl. District Number Club Name HH's 1/2 Dues Females Male TOTAL District 333 C 25243 ABIKO 5 5 6 7 13 District 333 C 25249 ASAHI 0 0 2 75 77 District 333 C 25254 BOSHUASAI L C 0 0 3 11 14 District 333 C 25257 CHIBA 9 8 9 51 60 District 333 C 25258 CHIBA CHUO 3 3 4 21 25 District 333 C 25259 CHIBA ECHO 0 0 2 24 26 District 333 C 25260 CHIBA KEIYO 0 0 1 19 20 District 333 C 25261 CHOSHI 2 2 1 45 46 District 333 C 25266 FUNABASHI 4 4 5 27 32 District 333 C 25267 FUNABASHI CHUO 5 5 8 56 64 District 333 C 25268 FUNABASHI HIGASHI 0 0 0 23 23 District 333 C 25269 FUTTSU 1 0 1 21 22 District 333 C 25276 ICHIKAWA 0 0 2 36 38 District 333 C 25277 ICHIHARA MINAMI 1 1 0 33 33 District 333 C 25278 ICHIKAWA HIGASHI 0 0 2 14 16 District 333 C 25279 IIOKA 0 0 0 36 36 District 333 C 25282 ICHIHARA 9 9 7 26 33 District 333 C 25292 KAMAGAYA 12 12 13 31 44 District 333 C 25297 KAMOGAWA 0 0 0 37 37 District 333 C 25299 KASHIWA 0 0 4 41 45 District 333 C 25302 BOSO KATSUURA L C 0 0 3 54 57 District 333 C 25303 KOZAKI 0 0 2 25 27 District 333 C 25307 KAZUSA 0 0 1 45 46 District 333 C 25308 KAZUSA ICHINOMIYA L C 0 0 1 26 27 District 333 C 25309 KIMITSU CHUO 0 0 1 18 19 District 333 C 25310 KIMITSU 5 5 14 42 56 District 333 C 25311 KISARAZU CHUO 1 1 5 14 19 District 333 C 25314 KISARAZU 0 0 1 14 15 District 333 C 25316 KISARAZU KINREI 3 3 5 11 16 District 333 C 25330 MATSUDO 0 0 0 27 27 District 333 C 25331 SOBU CHUO L C 0 0 0 39 39 District 333 C -

List of Approved Sending Organization (The Philippines)

LIST OF APPROVED SENDING ORGANIZATION (THE PHILIPPINES) ※フィリピンの認定送出機関については,フィリピン海外雇用庁(POEA)が運営する以下のURLにて,送出機関の名称を入力することにより,同機関の連絡先やライセンス の取得状況等を検索できます。 http://www.poea.gov.ph/cgi-bin/agSearch.asp Person in charge of Training Contact Point in Japan Approved date OTIT List No. Name of Organization Address URL Name of Person in (the date of No. Name TEL Email Address TEL Email Charge receipt) AC SICAT Blk. 5 Lot 9 Villa Lourdes Subd. 1 306 INTERNATIONAL Brgy. San Isidro Bacolor NONE ARTURO C. SICAT 9661748085 [email protected] NONE NONE NONE NONE 2020/1/15 MANPOWER SERVICES Pampanga 6/F Metro Lifestyle Complex, F. A. KANAN MANPOWER www.akananmanpower. 2 2 Torres St., cor. Jacinto St., Davao HISANO HORI (053) 482-8451 N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A 2018/6/1 CORPORATION com City 2-24-22, Bunkyo, Suite 501 AP Bldg. 1563 F. Minami-ku, AB INTERNATIONAL ELIAS FERNANDO [email protected] OLIVIA S. [email protected] 3 287 Agoncillo St. corner Pedro Gil www.abmanpower.com 523-6268 Sagamihara City +8142-701-0538 2019/7/4 PLACEMENT INC R. SALVADOR m KAWAGUCHI m Ermita, Manila, Philippines Kanagawa Pref. 252- 0307 11th Flr. Goldloop Tower A, Saitama Ken ABBA PERSONNEL [email protected] 4 155 Escriva Drive, Ortigas Center, www.abba.ph JENEVIEVE P. ORA 637-1324 [email protected] LALAINE KENDO Tokorozawa City 042-941-4152 2019/1/23 SERVICES INC. .jp Pasig City Matsuba Cho 20-23 ABD OVERSEAS 23 10 Marconi St. corner Morse www.abdrecruitment.co ANANIAS B. 843-4757 / 0917- [email protected] 5 8 MANPOWER N/A N/A N/A N/A 2018/6/1 St. -

![Growth Strategy for "Sustainable Management" [PDF:993KB]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7571/growth-strategy-for-sustainable-management-pdf-993kb-1047571.webp)

Growth Strategy for "Sustainable Management" [PDF:993KB]

Growth Strategy for “Sustainable Management” Medium Term Management Plan The 13th Medium Term Management Plan Best Bank 2020 Final stage-3 years of value co-creation From April 1, 2017 to March 31, 2020 This medium term management plan is for the final stage (three years) to accomplish our ultimate goal - to become the “best retail” banking group - by the target year of 2020 as set by the previous medium Our vision term management plan and to create the foundations for responding to environmental changes expected to occur over the medium to long term. We will bolster productivity and solidify customer confidence, and realize sustainable growth, by co-creating value (value co-creation) with our stakeholders, such as customers, shareholders, employees, and regional communities, etc. We aim to become the “best retail” banking group that provides top-class customer satisfaction through advanced services, and to be highly regarded by our regional customers, both individuals and SMEs. CS (Customer Satisfaction) ES (Employee Satisfaction) SS (Social Satisfaction) Ensure the “Customer Make a work environment Drive regional first policy” and respond where all employees can development, by speedily to customers’ realize their potential gathering the entire needs by providing with enthusiasm through Chiba Bank Group as the advanced services and diversity and work style leading bank in the area. solutions. reform. Key Issues Co-creating Realizing work style Strengthening 1 customer value 2 reforms that allow all 3 a sustainable employees to shine -

The Keihanshin Consortium for Fostering the Next

The Keihanshin Consortium for Fostering the Next Generation of Global Leaders in Research (K-CONNEX) Non-Tenure Program-Specific Assistant Professor Department of Electronic Science and Engineering, Graduate School of Engineering, Kyoto University November 20, 2015 In October 2014, Kyoto University, Osaka University and Kobe University decided to establish partnerships under a MEXT program, building a consortium for developing human resources in science and technology. The consortium, named as The Keihanshin Consortium for Fostering the Next Generation of Global Leaders in Research (K-CONNEX), promotes development and securement of excellent young researchers who will lead the future global academic community. We encourage such highly motivated young researchers to join the consortium through the following applications. 1. Target Research Areas Code No. 014KY1510 Job Type Program-Specific Assistant Professor with an annual salary No. Of 1 Positions Department of Electronic Science and Engineering, Graduate School of Engineering, Kyoto University Affiliation (Address: Kyoto University Katsura campus Nishigyo-ku, Kyoto 615-8530, Japan) Research Optical Engineering, Quantum Optoelectronics Fields We are recruiting top-class researchers who can develop artificial Research structural materials that can freely control light down to the Fields nanometer level. Applicants should be outstanding young (Details) researchers who aspire to “challenge the frontiers of physics” and “create new functions,” which the Department of Electronic Science and Engineering and the Photonics and Electronics Science and Engineering Center espouse, possess the advanced skills to do so, have already produced influential results in terms of benefiting society, and be recognized as having the talent to be a future PI. Term From the day of arrival at post to March 31, 2021 Discretionary labor system: Working hours are at the discretion of the worker with the standard working hours from 8:30 (starting Employment time) to 17:15 (ending time). -

Local Cuisines, Japanese Sake) That Has Been Nurtured by the Rich Nature of the Region: the Case of the Coastal Area in Chiba Prefecture, Japan

Food and Nutrition Sciences, 2013, 4, 964-971 http://dx.dor.org/10.4236/fns.2013.49125 Published Online September 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/fns) Traditional Food Culture (Local Cuisines, Japanese Sake) That Has Been Nurtured by the Rich Nature of the Region: The Case of the Coastal Area in Chiba Prefecture, Japan Korehisa Kaneko1*, Keiko Oshida2, Hajime Matsushima3 1Hokuso Creature Association, Tokyo, Japan; 2Department of Town Planning and Design, College of Science and Technology, Ni- hon University, Chiba, Japan; 3Research Faculty of Agriculture, Hokkaido University, Sapporo, Japan. Email: *[email protected] Received June 8th, 2013; revised July 8th, 2013; accepted July 15th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Korehisa Kaneko et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT In Chiba Prefecture, Japan, during the Edo period (1603-1867), the development of waterway traffic by ships and the management of ports, highways and post towns around the ports progressed with the prosperity of the Edo (present-day Tokyo), which became heavily populated and the center of politics. We estimated that the demand of Japanese sake, which is luxury grocery item, was high. The freshwater layer that is abundant in mineral water to a depth of approxi- mately 10 m is formed in coastal sand dunes. The fresh water layer is hard water, in which the concentrations of miner- als such as calcium and magnesium are high. When the fresh water layer is used as the preparation water, the working rice malt and yeast in the sake brewing process become active.