SWEDEN Mapping Digital Media: Sweden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Katso Televisiota, Maksukanavia Ja Makuunin Vuokravideoita 4/2017 Missä Ja Millä Vain

KATSO TELEVISIOTA, MAKSUKANAVIA JA MAKUUNIN VUOKRAVIDEOITA 4/2017 MISSÄ JA MILLÄ VAIN. WATSON TOIMII TIETOKONEELLA, TABLETISSA JA ÄLYPUHELIMESSA SEKÄ TV-TIKUN TAI WATSON-BOKSIN KANSSA TELEVISIOSSA. WATSON-PERUSPALVELUN KANAVAT 1 Yle TV1 12 FOX WATSONISSA 2 Yle TV2 13 AVA MYÖS 3 MTV3 14 Hero 4 Nelonen 16 Frii MAKUUNIN 5 Yle Fem / SVT World 18 TLC UUTUUSLEFFAT! 6 Sub 20 National Geographic 7 Yle Teema Channel 8 Liv 31 Yle TV1 HD 9 JIM 32 Yle TV2 HD Powered by 10 TV5 35 Yle Fem HD 11 KUTONEN 37 Yle Teema HD Live-tv-katselu. Ohjelma/ohjelmasarjakohtainen tallennus. Live-tv-katselu tv-tikun tai Watson-boksin kautta. Ohjelma/ohjelmasarjakohtainen tallennus. Live-tv-katselu Watson-boksin kautta. Ohjelma/ohjelmasarjakohtainen tallennus. Vain live-tv-katselu Watson-boksin kautta. Vain live-tv-katselu. KANAVAPAKETTI €/KK, KANAVAPAIKKA, KANAVA Next 21 Discovery Channel C 60 C More First Sports 121 Eurosport 1 HD *1 0,00 € 22 Eurosport 1 C 61 C More First HD 8,90 € 122 Eurosport 2 HD 23 MTV C 62 C More Series 123 Eurosport 2 24 Travel Channel C 63 C More Series HD 159 Fuel TV HD 25 Euronews C 64 C More Stars 160 Motors TV HD 27 TV7 C 66 C More Hits 163 Extreme Sports HD Start 33 MTV3 HD *1 C 67 SF Kanalen 200 Nautical Channel 0,00 € C 75 C More Juniori Base 126 MTV Live HD *1 C More Sport S Pakettiin sisältyy oheisella 8,90 € 150 VH1 Swedish 40 SVT1 4,30 € 41 SVT2 24,95 € tunnuksella merkityt 151 Nick Jr. -

The World Internet Project International Report 6Th Edition

The World Internet Project International Report 6th Edition THE WORLD INTERNET PROJECT International Report ̶ Sixth Edition Jeffrey I. Cole, Ph.D. Director, USC Annenberg School Center for the Digital Future Founder and Organizer, World Internet Project Michael Suman, Ph.D., Research Director Phoebe Schramm, Associate Director Liuning Zhou, Ph.D., Research Associate Interns: Negin Aminian, Hany Chang, Zoe Covello, Ryan Eason, Grace Marie Laffoon‐Alejanre, Eunice Lee, Zejun Li, Cheechee Lin, Guadalupe Madrigal, Mariam Manukyan, Lauren Uba, Tingxue Yu Written by Monica Dunahee and Harlan Lebo World Internet Project International Report ̶ Sixth Edition | i WORLD INTERNET PROJECT – International Report Sixth Edition Copyright © 2016 University of Southern California COPIES You are welcome to download additional copies of The World Internet Project International Report for research or individual use. However, this report is protected by copyright and intellectual property laws, and cannot be distributed in any way. By acquiring this publication you agree to the following terms: this copy of the sixth edition of the World Internet Project International Report is for your exclusive use. Any abuse of this agreement or any distribution will result in liability for its illegal use. To download the full text and graphs in this report, go to www.digitalcenter.org. ATTRIBUTION Excerpted material from this report can be cited in media coverage and institutional publications. Text excerpts should be attributed to The World Internet Project. Graphs should be attributed in a source line to: The World Internet Project International Report (sixth edition) USC Annenberg School Center for the Digital Future REPRINTING Reprinting this report in any form other than brief excerpts requires permission from the USC Annenberg School Center for the Digital Future at the address below. -

Kanalplan Laholm (HC561)

C561000 150331 Kanalplan Laholm (HC561) SVT1 Sveriges Televisions huvudkanal, med ett utbud som omfattar allt från familjeunderhållning till debattprogram, barnprogram och kultur. Kanalplats 04. SVT2 Sveriges Televisions andra kanal, med ett utbud som omfattar allt från familjeunderhållning till debattprogram, barnprogram och kultur. Kanalplats 06. TV4 Den breda svenska underhållningskanalen med populära serier, filmer, sport, nyheter och dokumentärer. Kanalplats S10 E8. Barnkanalen SVT:s egna, reklamfria barnkanal varvar klassiska favoriter med nya produktioner. Kanalen fokuserar även på interaktivitet och barnens egen medverkan. Kanalplats S14. Kunskapskanalen SVTs kanal som sänder program inom ämnesområden som historia, natur, vetenskap, kultur, omvärld och språk. Kanalplats S16. SVT 24 Temakanal för sport och nyheter. Samhällsprogram och fördjupningar varvas med en mängd olika sporter. Kanalplats S14. TV 3 är kanalen som bjuder på underhållande program i form av film, serier, talkshows etc. Kanalplats E9. Kanal 5 är en av Sveriges största TV-kanaler och gör TV för moderna och aktiva människor, med inriktning på underhållning, serier, drama och film. Kanalplats 11. TV 6 är den nya breda underhållningskanalen. Kanalen är ett perfekt komplement till TV3 och ger dig bl a sport, actionfilmer, humor och realityserier. Kanalplats S19. Sjuan Sjuan är en bred kvinnlig kanal som bjuder på mängder av färgstark underhållning i form av realityserier, dramaserier, filmer och spänning. Kanalplats 12. Discovery Channel Unika produktioner om forskning, vetenskap, teknik, natur och historia. Kanalplats S18. MTV Europas mest populära musikkanal med intervjuer, livespelningar, hitlistor och mycket mer – dygnet runt! Kanalplats S15. TV 8 Svensk aktualitetskanal som blandar nyheter, inrikes- och utrikesmagasin och dokumentärer med filmer och underhållning. Kompletteras med börsinfo från Bloomberg, DiTV och nyheter från Deutsche Welle. -

How a Traditional Daily Newspaper Reinvented Itself on Social

NEVER MISS A STORY. CASE STUDY HOW A TRADITIONAL DAILY NEWSPAPER REINVENTED ITSELF ON SOCIAL CASE SVENSKA DAGBLADET Table of CONTENTS COMPANY BACKGROUND 4 CHALLENGE: OVERCOMING THE CONSERVATIVE THINKING 5 CATCHING UP WITH THEIR MAIN COMPETITOR 6 IMMEDIATE AND LONG TERM GOALS 7 ABOUT THIS CASE STUDY 8 CONTACT 8 Svenska Dagbladet Case Study 3 +152% +74K +268K GROWTH IN SOCIAL GROWTH IN FANS ON NEW MONTHLY PAGE MEGIA ENGAGEMENT FACEBOOK PAGE * ENGAGEMENT AND SHARES * Within 12 months “Before EzyInsights it was much harder to motivate people when they couldn’t see how their stories were doing in real-time. EzyInsights has given a motivation boost for everyone, including all our journalists. “ HANNA ÖSTERBERG SOCIAL MEDIA MANAGER SVD, SCHIBSTED 4 How a traditional daily newspaper reinvented itself on social company BACKGROUND Svenska Dagbladet grew their tiny social presence to become the number one morning news publication in Sweden. From a print mindset with a disconnect between the editorial and social teams, to a fully data integrated news team. Over a 2 year period, they increased their daily on-post engagement from under 1k per day ton an average of over 3.5k. INDUSTRY: LOCATION: COMPANY SIZE: EZYINSIGHTS Daily Stockholm, 220 People USERS: Newspaper Sweden 68 People Svenska Dagbladet Case Study 5 challenge OVERCOMING THE CONSERVATIVE THINKING Established in 1884, SvD was a very traditional daily newspaper struggling in 2014 with their social presence. Their key challenges were overcoming the conservative, print and website only way of thinking, reacting more quickly to the social news cycle and being able to present news items more effectively on social platforms. -

Sweden Is Converting to Digital Television! the Switchover to Digital

1/3 Sweden is converting to digital television! Is your television ready? The switchover to digital television is starting! A Riksdag decision The Riksdag has decided that all of Sweden is to convert to digital television broadcasting in the terrestrial network no later than 1 February 2008. Gotland, Gävle and Motala are the first three transmission areas to convert. Gotland will begin 19 September 2005, Gävle on 10 October 2005 and Motala on 21 November 2005. This means that analogue terrestrial broadcasts in these areas will gradually be phased out and completely terminated by 13 December 2005. More channels Digital television provides better images, sound and new services such as electronic programme guides and more advanced text television. Most importantly however, all households will be able to receive more channels. The existing analogue terrestrial network is fully utilized and can only accommodate channels SVT1, SVT2 and TV4, despite the considerable demand for a broader selection. Most households have already arranged more channels via cable or satellite. Digital technology enables as many as between five and seven digital channels to be carried in the space used by analogue signals to carry one channel. The digital terrestrial network has been gradually expanded to generate more space for many more channels. Two networks, too expensive Less than 25% of all households still use the analogue terrestrial network to watch television. Costs for maintenance and service of two parallel networks – the old analogue and the new digital – is too expensive in the long term which is why we are switching over to acommon television network based on modern technology. -

Softathome Powers Boxer's Next Generation TV

SoftAtHome Powers Boxer’s Next Generation TV Nordic Operator Boxer Selects the SoftAtHome Operating Platform to Launch New Services Amsterdam, September 10th, 2010 - SoftAtHome, a software provider of home operating platforms that help Service Providers deliver convergent applications for the Digital Home, announced today that Boxer TV Access AB, the leading provider of terrestrial TV in the Nordic region, has selected the SoftAtHome Operating Platform to power its next generation TV offering including HDTV over DVB-T2 in combination with On Demand services over Internet. The two companies will collaborate to bring to market a next generation terrestrial offering and to enable the development of innovative features for Nordic subscribers. SoftAtHome provides an open, ubiquitous and carrier class software platform that enables Service Providers to create innovative and convergent applications for the Digital Home. It contains all the features and APIs necessary to create innovative and convergent applications. Service Providers and 3d party application developers can combine services such as voice, video, user interface, security, network access, connectivity or management, and deploy them across different devices in the home including Set Top Boxes (STB) and Home Gateways (HGW). “Boxer aims at providing access to a large number of paid and free to air terrestrial TV channels across the Nordic region. Our next generation TV offering will deliver a unique user experience on different types of STBs “, said Håkan Brander, Director Product Management & Development of Boxer. “We were looking for a solution that could provide a consistent user experience across different STBs. It was also key for Boxer to be able to find a software platform with the flexibility to develop the services of our choices today and in the future. -

Hur Digital-TV-Distributörer Bygger Relationer Med Kunder

Södertörns Högskola Institutionen för företagsekonomi och företagande Företagsekonomi, Kandidatuppsats 10 poäng Vårterminen 2006 Digital-TV Hur digital-TV-distributörer bygger relationer med kunder Författare: Clara Siwertz Stefan Tägt Handledare: Ted Modin i Sammanfattning 1997 kom riksdagen med ett förslag om att genomföra ett teknikskifte inom Sveriges marksända TV-distribution. Teknikskiftet skulle innebära att de analoga TV-sändningarna via marknätet skulle ersättas med digitala TV-sändningar och övergången skulle därför bidra med en mängd ekonomiska och tekniska fördelar. Digital-TV-sändningar erbjöds sedan tidigare av ett fåtal TV-distributörer men skulle nu bli något som fler TV-konsumenter skulle få tillgång till. Digital-TV-övergången är nu i full gång och påverkar såväl konsumenter som distributörer av digital-TV produkter och tjänster. Syftet med uppsatsen är att undersöka hur två digital-TV- distributörer anpassar sin marknadsföring för att stärka relationer till befintliga kunder och skapa relationer till nya kunder. Uppsatsen fokuserar på huruvida distributörerna tillämpar transaktionsmarknadsföring eller relationsmarknadsföring och hur den rådande digital-TV- övergången påverkar marknadsföringen. Teorier bakom relationsmarknadsföring fokuserar bland annat på relationen mellan leverantör och kund och detta är det centrala temat i uppsatsen. Värdeskapande, involvering, anpassningsförmåga, informationshantering, kundvård och CRM är några av de saker som studeras på respektive företag. Canal Digital AB och Boxer TV Access AB är de två distributörerna som undersöks och uppsatsen avgränsas till deras verksamhet i Sverige. Resultatet av undersökningen tyder på att distributörerna är väl medvetna om vikten av relationen till deras kunder. Flera exempel visar på att företagen arbetar aktivt för att vårda befintliga kunder och dessutom skapa nya relationer med kunder. -

The Nordic Model in Europe

The Nordic model in Europe Prostitution, trafficking and neo-abolitionism Daniela Burba Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Scienze Per la Pace Università di Pisa European Law and Gender 2020/2021 2 Index 0.Introduction 3 1.Western perspectives on prostitution 3 1.1 Feminist perspectives: a gender trouble 3 1.2 The issue of human trafficking 5 2.The Nordic model 7 2.1 Nordic model: Sweden 7 2.2 Legal framework and legacy 8 3.Assessing the impact of the criminalisation of sex purchase 10 3.1 Trafficking and immigration 10 3.2 International outcry against criminalisation 11 3.3 A comparison with regulatory policies: The Netherlands 13 4.New challenges 15 4.1 Covid-19 and job insecurity 15 5.Conclusions: the need for new perspectives 17 6. Bibliography 18 Cover images sources: http://vancouver.mediacoop.ca/story/stop-backpagecom-taking-stand-against-prostitution-an d-trafficking-women/9034 and https://www.nydailynews.com/news/world/canada-supreme-court-strikes-anti-prostitution-law s-article-1.1553892 (accessed 13/01/2021) 3 0.Introduction Policies over prostitution in Europe and globally have widely diversified in the last few decades, shaping a legal and social landscape that deeply affected the activity, wellbeing and perception of the individuals involved. Countries’ anxiety over the body of the prostitute and their visible presence is to a considerable extent a consequence of feminist discourse and counterposing ideologies over the body of women, an approach developed within a deeply gendered spectrum. The increasing concern over trafficking in persons for sexual purposes has also encouraged the international community and national governments to develop a new range of policies to tackle a phenomenon that seems to be out of control due to the globalised world’s heightened mobility. -

Hur Objektiv Är Den Svenska Storstadspressen?

Hur objektiv är den svenska storstadspressen? - En granskning av 2014 års valrörelse Erik Elowsson Institutionen för mediestudier Examensarbete 15 hp Vårterminen 2015 Medie- och Kommunikationsvetenskap Handledare: Göran Leth Examinator: Anja Hirdman Sammanfattning I denna uppsats används kvantitativ innehållsanalys för att pröva storstadspressens objektivitet gällande rapporteringen om valrörelsen 2014. Storstadspressen definieras som de fyra stockholmstidningarna: Aftonbladet, Expressen, Dagens Nyheter och Svenska Dagbladet. Syftet är att kartlägga hur dessa tidningar rapporterar om sammanhållningen inom de två politiska blocken, Alliansen och De rödgröna, vilka konkurrerar om att bilda regering efter valet. Objektivitet har operationaliserats som opartiskhet, vilket avser att medier balanserar uppmärksamheten och graden av positiv och negativ framställning mellan parterna i ett givet sammanhang. Resultaten indikerade att storstadspressens rapportering av valrörelsen, med avseende på sammanhållningen inom blocken, gynnade Alliansen mer än De rödgröna och att skillnaderna mellan tidningarna var betydande. För två av fyra tidningar kunde partiskhetsutlåtanden göras, där en bedöms som partisk och en som opartisk. Dagens Nyheters rapportering bedömdes som partisk, då Alliansens fick betydligt mer uppmärksamhet och nästan uteslutande positiv uppmärksamhet, samtidigt som De rödgröna fick avsevärt mindre utrymme och mestadels negativ uppmärksamhet. Svenska Dagbladet å andra sidan lyckades balansera sin rapportering mellan blocken, både i fråga -

C2WG3 Progress Report

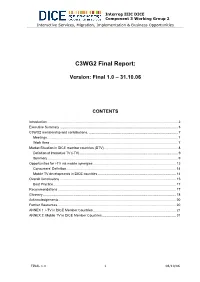

Interreg IIIC DICE Component 3 Working Group 2 Interactive Services, Migration, Implementation & Business Opportunities C3WG2 Final Report: Version: Final 1.0 – 31.10.06 CONTENTS Introduction............................................................................................................................................. 2 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................... 3 C3WG2 membership and contributions. ................................................................................................ 7 Meetings............................................................................................................................................. 7 Work Area .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Market Situation in DICE member countries (DTV) ............................................................................... 8 Definition of Interactive TV (i-TV).......................................................................................................... 9 Summary ............................................................................................................................................ 9 Opportunities for i-TV via mobile synergies ......................................................................................... 13 Consumers’ Definition..................................................................................................................... -

Det Är Så Det Ska Vara” – Eller?

Journalistgranskning Journalistprogrammet termin 3 JMG, Göteborgs Universitet Handledare: Marina Ghersetti ”Det är så det ska vara” – eller? En jämförelse mellan Rapport, Aktuellt och TV4Nyheterna 1985-2009 ADRIANNA PAVLICA MARI TVEITAN 2 Innehåll Bakgrund LEDARE Sveriges TV-historia i årtal 4 När svenska folket får säga sitt ligger TV-nyheterna högt i kurs. Undersök- Mannen som ville tala med tittarna 7 ningar har visat att vi hyser ett stort förtroende för TV-mediet, framför allt Galtung och gänget 10 SVT. Det är inte något vi funderat särskilt mycket över – förrän vi själva Mångfald är uppdraget 11 gjorde nyhetssändningar på JMG och insåg att nyhetsurvalet väldigt lätt blir en rutin där mycket tycks självklart. INnehåll Så finns det egentligen några skillnader i nyhetsvärderingen, innehållet och ”Det är så det ska vara” – eller? 12 presentationen mellan Rapport, Aktuellt och TV4Nyheterna? Och vad har Brott, ekonomi, politik, naturkatastrofer, sport... 14 det funnits för likheter och skillnader mellan och inom programmen över Männen tar plats 17 tid? Just eftersom förtroendet för TV-nyheterna är så stort tycker vi att det ”Dåliga nyheter är viktiga nyheter” 20 är viktigt att undersöka om tittarna får ta del av en god och mångfacetterad journalistik som präglas av mångfald och olika perspektiv. En annorlunda världsbild 22 Kommentar om innehåll 25 Det är journalisterna på SVT och TV4 som bestämmer vad som ska visas i TV-nyheterna, och frågan är hur mycket de egentligen diskuterar formen reportaget och innehållet. Vi vill också se hur journalisterna själva ser på nyhetsutbudet En dag på redaktionen 26 och om de tycker att de uppfyller den mångfald de eftersträvar. -

Digital-Tv-Kommissionens Slutrapport, KU 2004:04

I den här slutrapporten från Digital-tv-kommissionen beskrivs • Informationsmodellen – en kampanjstomme bestående av DR, planering och genomförande av den svenska digital-tv-övergången. annonsering och lokala möten har successivt rullats ut lokalt i Som ett av världens första länder genomförde Sverige 2004-2008 landet i takt med att övergången har nått nya områden. ett teknikskifte som direkt eller indirekt berörde drygt 4 miljoner • Nedsläckningsstrategin – modellen med en gradvis övergång hushåll. Lärdomarna är många och de fyra enskilt viktigaste fram- genom Sverige har inneburit möjlighet till lokalanpassade informa- gångsfaktorerna är: tionsaktiviteter och kontinuerlig utveckling av produktutbudet. • Samarbetet – genomförandet av övergången har byggt på en Digital-tv-kommissionen hoppas att denna slutrapport ska kunna framgångsrik samarbetsmodell mellan de inblandade huvudaktö- bidra med viktiga erfarenheter och kunskap inför liknande projekt rerna: Digital-tv-kommissionen, Teracom, SVT och TV4. både inom och utanför Sverige. • Varumärket – det gemensamma varumärket ”Digital-tv-övergången” har bidragit till fokus och en tydlig avsändare för projektet. SLU T- RAPPORT Digital-tv-kommissionens slutrapport, KU 2004:04 010101010101010101010101010101010101010 010101010101010101010101010101010101010 010101010101010101010101010101010101010 010101010101010101010101010101010101010 010101010101010101010101010101010101010 010101010101010101010101010101010101010 010101010101010101010101010 101010101010 010101010101010101010101010101010101010