Msczoo14.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Slugs of Britain & Ireland

TEST VERSION 2013 SLUGS OF BRITAIN & IRELAND (Short test version, pages 18-37 only) By Ben Rowson, James Turner, Roy Anderson & Bill Symondson PRODUCED BY FSC 2013. TEXT AND PHOTOS © NATIONAL MUSEUM OF WALES 2013 External features of slugs Tail Mantle Head Keel Tubercles Lateral bands Genital pore Identification of Slugs Identification Tentacles. Breathing pore (pneumostome) Keel Eyes Variations in lateral banding Mantle markings and ridges Broken lateral bands Mouth Solid lateral bands Sole (underside of foot) Mantle. Note texture and presence of grooves and ridges, as Tubercles. Note whether numerous and small/fine vs. few and well as any markings and banding. large/coarse. Pigment may be present in the grooves between tubercles. Tentacles. Note colour. Slugs may need to be handled or disturbed to extend tentacles. Keel (raised ridge). Note length and whether truncated at the tip of tail. Beware markings that may exaggerate or obscure the Breathing pore (pneumostome). length of keel. On right-hand side of body. Note whether rim is noticeably paler or darker than body sides. Sole (underside of foot). Note colour and any patterning. The sole in most slugs is tripartite i.e. there are three fields running Lateral bands. Note whether present on mantle and/or tail. in parallel the length of the animal. Is the central field a different Note also intensity, whether broad or narrow, and whether high shade from the lateral fields or low on body side. Shell Dorsal grooves. In Testacellidae, note wheth- Mucus pore. er the two grooves meet in front of the shell or Present only in Arionidae underneath it. -

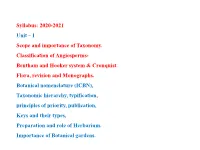

I Scope and Importance of Taxonomy. Classification of Angiosperms- Bentham and Hooker System & Cronquist

Syllabus: 2020-2021 Unit – I Scope and importance of Taxonomy. Classification of Angiosperms- Bentham and Hooker system & Cronquist. Flora, revision and Monographs. Botanical nomenclature (ICBN), Taxonomic hierarchy, typification, principles of priority, publication, Keys and their types, Preparation and role of Herbarium. Importance of Botanical gardens. PLANT KINGDOM Amongst plants nearly 15,000 species belong to Mosses and Liverworts, 12,700 Ferns and their allies, 1,079 Gymnosperms and 295,383 Angiosperms (belonging to about 485 families and 13,372 genera), considered to be the most recent and vigorous group of plants that have occurred on earth. Angiosperms occupy the majority of the terrestrial space on earth, and are the major components of the world‘s vegetation. Brazil (First) and Colombia (second), both located in the tropics considered to be countries with the most diverse angiosperms floras China (Third) even though the main part of her land is not located in the tropics, the number of angiosperms still occupies the third place in the world. In INDIA there are about 18042 species of flowering plants approximately 320 families, 40 genera and 30,000 species. IUCN Red list Categories: EX –Extinct; EW- Extinct in the Wild-Threatened; CR -Critically Endangered; VU- Vulnerable Angiosperm (Flowering Plants) SPECIES RICHNESS AROUND THE WORLD PLANT CLASSIFICATION Historia Plantarum - the earliest surviving treatise on plants in which Theophrastus listed the names of over 500 plant species. Artificial system of Classification Theophrastus attempted common groupings of folklore combined with growth form such as ( Tree Shrub; Undershrub); or Herb. Or (Annual and Biennials plants) or (Cyme and Raceme inflorescences) or (Archichlamydeae and Meta chlamydeae) or (Upper or Lower ovarian ). -

Review and Updated Checklist of Freshwater Fishes of Iran: Taxonomy, Distribution and Conservation Status

Iran. J. Ichthyol. (March 2017), 4(Suppl. 1): 1–114 Received: October 18, 2016 © 2017 Iranian Society of Ichthyology Accepted: February 30, 2017 P-ISSN: 2383-1561; E-ISSN: 2383-0964 doi: 10.7508/iji.2017 http://www.ijichthyol.org Review and updated checklist of freshwater fishes of Iran: Taxonomy, distribution and conservation status Hamid Reza ESMAEILI1*, Hamidreza MEHRABAN1, Keivan ABBASI2, Yazdan KEIVANY3, Brian W. COAD4 1Ichthyology and Molecular Systematics Research Laboratory, Zoology Section, Department of Biology, College of Sciences, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran 2Inland Waters Aquaculture Research Center. Iranian Fisheries Sciences Research Institute. Agricultural Research, Education and Extension Organization, Bandar Anzali, Iran 3Department of Natural Resources (Fisheries Division), Isfahan University of Technology, Isfahan 84156-83111, Iran 4Canadian Museum of Nature, Ottawa, Ontario, K1P 6P4 Canada *Email: [email protected] Abstract: This checklist aims to reviews and summarize the results of the systematic and zoogeographical research on the Iranian inland ichthyofauna that has been carried out for more than 200 years. Since the work of J.J. Heckel (1846-1849), the number of valid species has increased significantly and the systematic status of many of the species has changed, and reorganization and updating of the published information has become essential. Here we take the opportunity to provide a new and updated checklist of freshwater fishes of Iran based on literature and taxon occurrence data obtained from natural history and new fish collections. This article lists 288 species in 107 genera, 28 families, 22 orders and 3 classes reported from different Iranian basins. However, presence of 23 reported species in Iranian waters needs confirmation by specimens. -

International Code of Zoological Nomenclature

International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature INTERNATIONAL CODE OF ZOOLOGICAL NOMENCLATURE Fourth Edition adopted by the International Union of Biological Sciences The provisions of this Code supersede those of the previous editions with effect from 1 January 2000 ISBN 0 85301 006 4 The author of this Code is the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature Editorial Committee W.D.L. Ride, Chairman H.G. Cogger C. Dupuis O. Kraus A. Minelli F. C. Thompson P.K. Tubbs All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise), without the prior written consent of the publisher and copyright holder. Published by The International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature 1999 c/o The Natural History Museum - Cromwell Road - London SW7 5BD - UK © International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature 1999 Explanatory Note This Code has been adopted by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature and has been ratified by the Executive Committee of the International Union of Biological Sciences (IUBS) acting on behalf of the Union's General Assembly. The Commission may authorize official texts in any language, and all such texts are equivalent in force and meaning (Article 87). The Code proper comprises the Preamble, 90 Articles (grouped in 18 Chapters) and the Glossary. Each Article consists of one or more mandatory provisions, which are sometimes accompanied by Recommendations and/or illustrative Examples. In interpreting the Code the meaning of a word or expression is to be taken as that given in the Glossary (see Article 89). -

Tracing History

Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 911 Tracing History Phylogenetic, Taxonomic, and Biogeographic Research in the Colchicum Family BY ANNIKA VINNERSTEN ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS UPPSALA 2003 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Lindahlsalen, EBC, Uppsala, Friday, December 12, 2003 at 10:00 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Abstract Vinnersten, A. 2003. Tracing History. Phylogenetic, Taxonomic and Biogeographic Research in the Colchicum Family. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 911. 33 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 91-554-5814-9 This thesis concerns the history and the intrafamilial delimitations of the plant family Colchicaceae. A phylogeny of 73 taxa representing all genera of Colchicaceae, except the monotypic Kuntheria, is presented. The molecular analysis based on three plastid regions—the rps16 intron, the atpB- rbcL intergenic spacer, and the trnL-F region—reveal the intrafamilial classification to be in need of revision. The two tribes Iphigenieae and Uvularieae are demonstrated to be paraphyletic. The well-known genus Colchicum is shown to be nested within Androcymbium, Onixotis constitutes a grade between Neodregea and Wurmbea, and Gloriosa is intermixed with species of Littonia. Two new tribes are described, Burchardieae and Tripladenieae, and the two tribes Colchiceae and Uvularieae are emended, leaving four tribes in the family. At generic level new combinations are made in Wurmbea and Gloriosa in order to render them monophyletic. The genus Androcymbium is paraphyletic in relation to Colchicum and the latter genus is therefore expanded. -

The Slugs of Bulgaria (Arionidae, Milacidae, Agriolimacidae

POLSKA AKADEMIA NAUK INSTYTUT ZOOLOGII ANNALES ZOOLOGICI Tom 37 Warszawa, 20 X 1983 Nr 3 A n d rzej W ik t o r The slugs of Bulgaria (A rionidae , M ilacidae, Limacidae, Agriolimacidae — G astropoda , Stylommatophora) [With 118 text-figures and 31 maps] Abstract. All previously known Bulgarian slugs from the Arionidae, Milacidae, Limacidae and Agriolimacidae families have been discussed in this paper. It is based on many years of individual field research, examination of all accessible private and museum collections as well as on critical analysis of the published data. The taxa from families to species are sup plied with synonymy, descriptions of external morphology, anatomy, bionomics, distribution and all records from Bulgaria. It also includes the original key to all species. The illustrative material comprises 118 drawings, including 116 made by the author, and maps of localities on UTM grid. The occurrence of 37 slug species was ascertained, including 1 species (Tandonia pirinia- na) which is quite new for scientists. The occurrence of other 4 species known from publications could not bo established. Basing on the variety of slug fauna two zoogeographical limits were indicated. One separating the Stara Pianina Mountains from south-western massifs (Pirin, Rila, Rodopi, Vitosha. Mountains), the other running across the range of Stara Pianina in the^area of Shipka pass. INTRODUCTION Like other Balkan countries, Bulgaria is an area of Palearctic especially interesting in respect to malacofauna. So far little investigation has been carried out on molluscs of that country and very few papers on slugs (mostly contributions) were published. The papers by B a b o r (1898) and J u r in ić (1906) are the oldest ones. -

Zootaxa, Type Specimens, Samples of Live Individuals and the Galapagos

Zootaxa 2201: 12–20 (2009) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Editorial ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2009 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Type specimens, samples of live individuals and the Galapagos Pink Land Iguana THOMAS M. DONEGAN 1 1 Fundación ProAves, 33 Blenheim Road, Caversham, Reading, RG4 7RT, UK [email protected] or [email protected] Abstract The nomenclatural implications of Gentile & Snell (2009)'s innovations in the designation of a type specimen - that is sampled and tagged but not killed - are discussed. The paper also responds to Nemésio (2009)'s criticism of Donegan (2008), where I argued that descriptions based on samples of live individuals are valid. I also discuss whether recent descriptions of such a nature involve a different degree of scientific rigour to other descriptions. Key words: Nomenclatural availability, vouchers, collecting, specimen, type specimen, sample, ethics, framework, Code, Commission, Conolophus marthae. Introduction In this issue of Zootaxa, Gentile & Snell (2009) describe a critically endangered new species of land iguana from the Gálapagos islands, named Conolophus marthae. Aside from being an important discovery, this description includes noteworthy innovations in the designation of a type specimen based on a live individual. In a recent exchange of papers in Zootaxa, the validity of descriptions based on a holotype which is not a full, dead specimen (such as this) have been discussed (Dubois & Nemésio 2007, Donegan 2008, Nemésio 2009). Dubois and Nemésio have expressed the viewpoint that descriptions based on live individuals are not valid nomenclatural acts. I have expressed the contrary view. Other recent descriptions based on holotypes which are not killed have relied solely upon photographs and, in some instances, samples taken from live individuals (see discussion in Donegan 2008). -

Note on the Sauropod and Theropod Dinosaurs from the Upper Cretaceous of Madagascar*

EXTRACT FROM THE BULLETIN DE LA SOCIÉTÉ GÉOLOGIQUE DE FRANCE 3rd series, volume XXIV, page 176, 1896. NOTE ON THE SAUROPOD AND THEROPOD DINOSAURS FROM THE UPPER CRETACEOUS OF MADAGASCAR* by Charles DEPÉRET. (PLATE VI). Translated by Matthew Carrano Department of Anatomical Sciences SUNY at Stony Brook, September 1999 The bones of large dinosaurian reptiles described in this work were brought to me by my good friend, Mr. Dr. Félix Salètes, primary physician for the Madagascar expedition, from the environs of Maevarana, where he was charged with installing a provisional hospital. This locality is situated on the right bank of the eastern arm of the Betsiboka, 46 kilometers south of Majunga, on the northwest coast of the island of Madagascar. Not having the time to occupy himself with paleontological studies, Dr. Salètes charged one of his auxiliary agents, Mr. Landillon, company sergeant-major of the marines, with researching the fossils in the environs of the Maevarana post. Thanks to the zeal and activity of Mr. Landillon, who was not afraid to gravely expose his health in these researches, I have been able to receive the precious bones of terrestrial reptiles that are the object of this note, along with an important series of fossil marine shells. I eagerly seize the opportunity here to thank Mr. Landillon for his important shipment and for the very precise geological data which he communicated to me concerning the environs of Maevarana, and of which I will now give a short sketch. 1st. Geology of Maevarana and placement of the localities. * Original reference: Depéret, C. -

Distribution of Angiostrongylus Vasorum and Its

Aziz et al. Parasites & Vectors (2016) 9:56 DOI 10.1186/s13071-016-1338-3 RESEARCH Open Access Distribution of Angiostrongylus vasorum and its gastropod intermediate hosts along the rural–urban gradient in two cities in the United Kingdom, using real time PCR Nor Azlina A. Aziz1,2*, Elizabeth Daly1, Simon Allen1,3, Ben Rowson4, Carolyn Greig3, Dan Forman3 and Eric R. Morgan1 Abstract Background: Angiostrongylus vasorum is a highly pathogenic metastrongylid nematode affecting dogs, which uses gastropod molluscs as intermediate hosts. The geographical distribution of the parasite appears to be heterogeneous or patchy and understanding of the factors underlying this heterogeneity is limited. In this study, we compared the species of gastropod present and the prevalence of A. vasorum along a rural–urban gradient in two cities in the south-west United Kingdom. Methods: The study was conducted in Swansea in south Wales (a known endemic hotspot for A. vasorum) and Bristol in south-west England (where reported cases are rare). In each location, slugs were sampled from nine sites across three broad habitat types (urban, suburban and rural). A total of 180 slugs were collected in Swansea in autumn 2012 and 338 in Bristol in summer 2014. A 10 mg sample of foot tissue was tested for the presence of A. vasorum by amplification of the second internal transcribed spacer (ITS-2) using a previously validated real-time PCR assay. Results: There was a significant difference in the prevalence of A. vasorum in slugs between cities: 29.4 % in Swansea and 0.3 % in Bristol. In Swansea, prevalence was higher in suburban than in rural and urban areas. -

International Buuetin Status of the Generic Name

Page 16 INTERNATIONAL BUUETIN STATUS OF THE GENERIC NAME BACTERIUM, THE SPECIFIC NAME BACTERIUM COLI .9M) THE FAMILY NAhE B.4CTERIACEAE Preliminary Statement, File No. 5 The Editorial Roard has prepared the followinq preliminary state- ment for consideration by the Judicial Commission and for the in- formation of the members of the Intervational Committee on Bact- eriological Nomenclatiire. It is a revision of a statement earlier circulated,and disciissed at the meetings of the Commission and of the Committee held at the time of the International Microbiolog- ical Conyress at Rio de Janeiro (1950). The Judicial Commission, through its Editorial Board, will he pleased to receive comments, criticisms and siiqqestions from any person interested. The Judicial Comnission has reveals much confusion with been asked to prepare and issiie reference to the use of the an opinion fixinp, the statiis of generic name Bacterium and of the qeneric name Bscteriurn Ehr- the family name Bacteriaceae. enbere;, of the specific name Proposal No.1 as submitted to Bacterium coli,and of the fam- the Commission seeks to elimin- ily name Bacterinceae. ate the conftlsion by the re- jection of these names,the F'ROPOSALS.Two proposals have second proposal would eliminate been received. the confusion by the careful definition of these names. 1.It is proposed that the ?en- eric nape Bacterium and the The following topics require family name Bacteriaceqe be de- examination : signated as nomin.7 rejicienda. A.Rejection or conservation of the generic name Bacterium Ehr- 2.It is proposed that the gen- enberg; 1828. eric name Bacterium and the R.Rejection or conservation of family name Bacteriaceae be de- the generic name Bacterium as signated as nomina conservanda, proposed or emended by later that the genus Bacterium be authors. -

Guidelines for the Capture and Management of Digital Zoological Names Information Francisco W

Guidelines for the Capture and Management of Digital Zoological Names Information Francisco W. Welter-Schultes Version 1.1 March 2013 Suggested citation: Welter-Schultes, F.W. (2012). Guidelines for the capture and management of digital zoological names information. Version 1.1 released on March 2013. Copenhagen: Global Biodiversity Information Facility, 126 pp, ISBN: 87-92020-44-5, accessible online at http://www.gbif.org/orc/?doc_id=2784. ISBN: 87-92020-44-5 (10 digits), 978-87-92020-44-4 (13 digits). Persistent URI: http://www.gbif.org/orc/?doc_id=2784. Language: English. Copyright © F. W. Welter-Schultes & Global Biodiversity Information Facility, 2012. Disclaimer: The information, ideas, and opinions presented in this publication are those of the author and do not represent those of GBIF. License: This document is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0. Document Control: Version Description Date of release Author(s) 0.1 First complete draft. January 2012 F. W. Welter- Schultes 0.2 Document re-structured to improve February 2012 F. W. Welter- usability. Available for public Schultes & A. review. González-Talaván 1.0 First public version of the June 2012 F. W. Welter- document. Schultes 1.1 Minor editions March 2013 F. W. Welter- Schultes Cover Credit: GBIF Secretariat, 2012. Image by Levi Szekeres (Romania), obtained by stock.xchng (http://www.sxc.hu/photo/1389360). March 2013 ii Guidelines for the management of digital zoological names information Version 1.1 Table of Contents How to use this book ......................................................................... 1 SECTION I 1. Introduction ................................................................................ 2 1.1. Identifiers and the role of Linnean names ......................................... 2 1.1.1 Identifiers .................................................................................. -

Describing Species

DESCRIBING SPECIES Practical Taxonomic Procedure for Biologists Judith E. Winston COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK Columbia University Press Publishers Since 1893 New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © 1999 Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data © Winston, Judith E. Describing species : practical taxonomic procedure for biologists / Judith E. Winston, p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-231-06824-7 (alk. paper)—0-231-06825-5 (pbk.: alk. paper) 1. Biology—Classification. 2. Species. I. Title. QH83.W57 1999 570'.1'2—dc21 99-14019 Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. Printed in the United States of America c 10 98765432 p 10 98765432 The Far Side by Gary Larson "I'm one of those species they describe as 'awkward on land." Gary Larson cartoon celebrates species description, an important and still unfinished aspect of taxonomy. THE FAR SIDE © 1988 FARWORKS, INC. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Universal Press Syndicate DESCRIBING SPECIES For my daughter, Eliza, who has grown up (andput up) with this book Contents List of Illustrations xiii List of Tables xvii Preface xix Part One: Introduction 1 CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 3 Describing the Living World 3 Why Is Species Description Necessary? 4 How New Species Are Described 8 Scope and Organization of This Book 12 The Pleasures of Systematics 14 Sources CHAPTER 2. BIOLOGICAL NOMENCLATURE 19 Humans as Taxonomists 19 Biological Nomenclature 21 Folk Taxonomy 23 Binomial Nomenclature 25 Development of Codes of Nomenclature 26 The Current Codes of Nomenclature 50 Future of the Codes 36 Sources 39 Part Two: Recognizing Species 41 CHAPTER 3.