Tracing History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Autumn Plants of the Peloponnese

Autumn Plants of the Peloponnese Naturetrek Tour Report 24 - 31 October 2018 Crocus goulimyi Chelmos Mystras Galanthus reginae-olgae Report& images by David Tattersfield Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Autumn Plants of the Peloponnese Tour participants: David Tattersfield (leader) and seven clients Day 1 Wednesday 24th October We made rapid progress along the motorway and stopped at Corinth to view the canal, which effectively makes the Peloponnese an island. Here we found our first flowers, the extremely common Autumn Squill Prospero autumnale, the striped, hooded spathes of Friar’s Cowl Arisarum vulgare, and a number of Crocus mazziaricus. A few butterflies included Long-tailed Blue, Lang’s Short-tailed Blue, Eastern Bath White, Mallow Skipper and a Pigmy Skipper. We continued along the newly-completed coast road, before turning inland and climbing steeply into the mountains. We arrived in Kalavrita around 6pm and after settling in to our hotel, we enjoyed a delicious meal of home-cooked food at a nearby taverna. Day 2 Thursday 25th October We awoke to a sunny day with cloud over the mountains. Above Kalavrita, we explored an area of Kermes Oak scrub and open pasture, where we found more white Crocus mazziaricus and Crocus melantherus. Crocus melantherus, as its name suggests can be distinguished from other autumn-flowering species by its black anthers and purple feathering on the outer tepals. Cyclamen hederifolium was common under the shade of the trees. -

Plant List 2016

Established 1990 PLANT LIST 2016 European mail order website www.crug-farm.co.uk CRÛG FARM PLANTS • 2016 Welcome to our 2016 list hope we can tempt you with plenty of our old favourites as well as some exciting new plants that we have searched out on our travels. There has been little chance of us standing still with what has been going on here in 2015. The year started well with the birth of our sixth grandchild. January into February had Sue and I in Colombia for our first winter/early spring expedition. It was exhilarating, we were able to travel much further afield than we had previously, as the mountainous areas become safer to travel. We are looking forward to working ever closer with the Colombian institutes, such as the Medellin Botanic Gardens whom we met up with. Consequently we were absent from the RHS February Show at Vincent Square. We are finding it increasingly expensive participating in the London shows, while re-branding the RHS February Show as a potato event hardly encourages our type of customer base to visit. A long standing speaking engagement and a last minute change of date, meant that we missed going to Fota near Cork last spring, no such problem this coming year. We were pleasantly surprised at the level of interest at the Trgrehan Garden Rare Plant Fair, in Cornwall. Hopefully this will become an annual event for us, as well as the Cornwall Garden Society show in April. Poor Sue went through the wars having to have a rush hysterectomy in June, after some timely results revealed future risks. -

Guide to the Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- LILIACEAE

Guide to the Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- LILIACEAE LILIACEAE de Jussieu 1789 (Lily Family) (also see AGAVACEAE, ALLIACEAE, ALSTROEMERIACEAE, AMARYLLIDACEAE, ASPARAGACEAE, COLCHICACEAE, HEMEROCALLIDACEAE, HOSTACEAE, HYACINTHACEAE, HYPOXIDACEAE, MELANTHIACEAE, NARTHECIACEAE, RUSCACEAE, SMILACACEAE, THEMIDACEAE, TOFIELDIACEAE) As here interpreted narrowly, the Liliaceae constitutes about 11 genera and 550 species, of the Northern Hemisphere. There has been much recent investigation and re-interpretation of evidence regarding the upper-level taxonomy of the Liliales, with strong suggestions that the broad Liliaceae recognized by Cronquist (1981) is artificial and polyphyletic. Cronquist (1993) himself concurs, at least to a degree: "we still await a comprehensive reorganization of the lilies into several families more comparable to other recognized families of angiosperms." Dahlgren & Clifford (1982) and Dahlgren, Clifford, & Yeo (1985) synthesized an early phase in the modern revolution of monocot taxonomy. Since then, additional research, especially molecular (Duvall et al. 1993, Chase et al. 1993, Bogler & Simpson 1995, and many others), has strongly validated the general lines (and many details) of Dahlgren's arrangement. The most recent synthesis (Kubitzki 1998a) is followed as the basis for familial and generic taxonomy of the lilies and their relatives (see summary below). References: Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (1998, 2003); Tamura in Kubitzki (1998a). Our “liliaceous” genera (members of orders placed in the Lilianae) are therefore divided as shown below, largely following Kubitzki (1998a) and some more recent molecular analyses. ALISMATALES TOFIELDIACEAE: Pleea, Tofieldia. LILIALES ALSTROEMERIACEAE: Alstroemeria COLCHICACEAE: Colchicum, Uvularia. LILIACEAE: Clintonia, Erythronium, Lilium, Medeola, Prosartes, Streptopus, Tricyrtis, Tulipa. MELANTHIACEAE: Amianthium, Anticlea, Chamaelirium, Helonias, Melanthium, Schoenocaulon, Stenanthium, Veratrum, Toxicoscordion, Trillium, Xerophyllum, Zigadenus. -

Ramson Confusable with Poisonous Plants

E-article from the National Food Institute no. 2, 2012 Ramson confusable with poisonous plants Kirsten Pilegaard Division of Toxicology and Risk Assessment National Food Institute, Technical University of Denmark ISSN: 1904-5581 Correctly identified ramson is not poisonous The National Food Institute, Technical University of Relatively little is known about the substances in ramson Denmark has assessed the possible toxic effects of compared to those in cultivated plants. Some studies have eating ramson, which in recent years has become a popular plant to gather and eat in Denmark. As such, chemically analysed the substances in ramson on its own or ramson does not contain harmful substances, but it compared them with the constituents found in for example, may be mistaken for poisonous plants. In particular, garlic (Allium sativum L.) or other onion (Allium) species. before flowering, ramson leaves can be confused with autumn crocus and lily of the valley. Several cases Ramson contains different types of sulphur-containing of poisoning have been reported in other European compounds, the so-called cysteine sulfoxides, which are countries, even with fatal consequences, as a result of also found in other onion species, for example garlic, and this confusion. various flavonoids (Schmitt et al. 2005, Štajner et al. 2008, Fritsch & Keugsen 2006). As such, ramson does not contain harmful substances. Ramson, bear garlic or wild garlic (Allium ursinum L.) has for a long time been used abroad, but new Nordic cuisine In reviewing the literature, the National Food Institute, in particular has made ramson gathering in Denmark a Technical University of Denmark, has not found any popular activity. -

Filogenia Y Genética Poblacional El Género Androcymbium

FILOGENIA Y GENÉTICA POBLACIONAL DEL GÉNERO ANDROCYMBIUM (COLCHICACEAE) Alberto DEL HOYO LEAL ISBN: 968-84-690-4262-5 Dipòsit legal: GI-1436-2006 FILOGENIA Y GENÉTICA POBLACIONAL DEL GÉNERO ANDROCYMBIUM (COLCHICACEAE) ALBERTO DEL HOYO LEAL Marzo 2006 JARDÍ BOTÀNIC MARIMURTRA Y FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA UNIVERSITAT DE GIRONA PROGRAMA DE DOCTORADO DE MEDIO AMBIENTE. BIENIO 2002 – 2004 FILOGENIA Y GENÉTICA POBLACIONAL DEL GÉNERO ANDROCYMBIUM (COLCHICACEAE) Memoria presentada para optar al título de Doctor en Biología por la Universitat de Girona por ALBERTO DEL HOYO LEAL DIRECTORES: DR. JOAN PEDROLA MONFORT Y DR. JOSÉ LUIS GARCÍA MARÍN Dr. JOAN PEDROLA MONFORT Dr. JOSÉ LUIS GARCÍA MARÍN Lab. de Biologia Evolutiva de Plantes, Dept. Lab. de Genètica, Dept. de Biologia, de Botànica, Facultat de Biològiques, Facultat de Ciències. Universitat de Universitat de València. Girona. ALBERTO DEL HOYO LEAL AGRADECIMIENTOS Al Dr. Joan Pedrola-Monfort y al Dr. José Luis García-Marín, por dirigirme la tesis doctoral. Al área de genética de la Universitat de Girona por haberme ayudado a secuenciar todas las muestras. A Laura Piferrer y Montse Samper, antiguas becarias del Jardí Botànic Marimurtra, por su inestimable ayuda en el análisis y la interpretación de los marcadores RAPD. Al Dr. Martí Cortey y a Manel Vera, por enseñarme toda las técnicas relacionadas con la secuenciación del DNA. Al Dr. Juli Caujapé-Castells y a la Dra. Nuria Membrives, por su interés y colaboración a la hora de discutir diferentes aspectos relacionados con el género Androcymbium . A la Dra. Karin Persson, por su inestimable ayuda en la discusión de diversos aspectos relacionados con el género Colchicum . -

BFS048 Site Species List

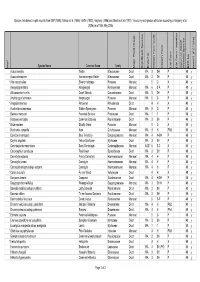

Species lists based on plot records from DEP (1996), Gibson et al. (1994), Griffin (1993), Keighery (1996) and Weston et al. (1992). Taxonomy and species attributes according to Keighery et al. (2006) as of 16th May 2005. Species Name Common Name Family Major Plant Group Significant Species Endemic Growth Form Code Growth Form Life Form Life Form - aquatics Common SSCP Wetland Species BFS No kens01 (FCT23a) Wd? Acacia sessilis Wattle Mimosaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Acacia stenoptera Narrow-winged Wattle Mimosaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y * Aira caryophyllea Silvery Hairgrass Poaceae Monocot 5 G A 48 y Alexgeorgea nitens Alexgeorgea Restionaceae Monocot WA 6 S-R P 48 y Allocasuarina humilis Dwarf Sheoak Casuarinaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Amphipogon turbinatus Amphipogon Poaceae Monocot WA 5 G P 48 y * Anagallis arvensis Pimpernel Primulaceae Dicot 4 H A 48 y Austrostipa compressa Golden Speargrass Poaceae Monocot WA 5 G P 48 y Banksia menziesii Firewood Banksia Proteaceae Dicot WA 1 T P 48 y Bossiaea eriocarpa Common Bossiaea Papilionaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y * Briza maxima Blowfly Grass Poaceae Monocot 5 G A 48 y Burchardia congesta Kara Colchicaceae Monocot WA 4 H PAB 48 y Calectasia narragara Blue Tinsel Lily Dasypogonaceae Monocot WA 4 H-SH P 48 y Calytrix angulata Yellow Starflower Myrtaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Centrolepis drummondiana Sand Centrolepis Centrolepidaceae Monocot AUST 6 S-C A 48 y Conostephium pendulum Pearlflower Epacridaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Conostylis aculeata Prickly Conostylis Haemodoraceae Monocot WA 4 H P 48 y Conostylis juncea Conostylis Haemodoraceae Monocot WA 4 H P 48 y Conostylis setigera subsp. -

Introduction Methods Results

Papers and Proceedings Royal Society ofTasmania, Volume 1999 103 THE CHARACTERISTICS AND MANAGEMENT PROBLEMS OF THE VEGETATION AND FLORA OF THE HUNTINGFIELD AREA, SOUTHERN TASMANIA by J.B. Kirkpatrick (with two tables, four text-figures and one appendix) KIRKPATRICK, J.B., 1999 (31:x): The characteristics and management problems of the vegetation and flora of the Huntingfield area, southern Tasmania. Pap. Proc. R. Soc. Tasm. 133(1): 103-113. ISSN 0080-4703. School of Geography and Environmental Studies, University ofTasmania, GPO Box 252-78, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia 7001. The Huntingfield area has a varied vegetation, including substantial areas ofEucalyptus amygdalina heathy woodland, heath, buttongrass moorland and E. amygdalina shrubbyforest, with smaller areas ofwetland, grassland and E. ovata shrubbyforest. Six floristic communities are described for the area. Two hundred and one native vascular plant taxa, 26 moss species and ten liverworts are known from the area, which is particularly rich in orchids, two ofwhich are rare in Tasmania. Four other plant species are known to be rare and/or unreserved inTasmania. Sixty-four exotic plantspecies have been observed in the area, most ofwhich do not threaten the native biodiversity. However, a group offire-adapted shrubs are potentially serious invaders. Management problems in the area include the maintenance ofopen areas, weed invasion, pathogen invasion, introduced animals, fire, mechanised recreation, drainage from houses and roads, rubbish dumping and the gathering offirewood, sand and plants. Key Words: flora, forest, heath, Huntingfield, management, Tasmania, vegetation, wetland, woodland. INTRODUCTION species with the most cover in the shrub stratum (dominant species) was noted. If another species had more than half The Huntingfield Estate, approximately 400 ha of forest, the cover ofthe dominant one it was noted as a codominant. -

Biodiversity and Ecology of Critically Endangered, Rûens Silcrete Renosterveld in the Buffeljagsrivier Area, Swellendam

Biodiversity and Ecology of Critically Endangered, Rûens Silcrete Renosterveld in the Buffeljagsrivier area, Swellendam by Johannes Philippus Groenewald Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters in Science in Conservation Ecology in the Faculty of AgriSciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof. Michael J. Samways Co-supervisor: Dr. Ruan Veldtman December 2014 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration I hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis, for the degree of Master of Science in Conservation Ecology, is my own work that have not been previously published in full or in part at any other University. All work that are not my own, are acknowledge in the thesis. ___________________ Date: ____________ Groenewald J.P. Copyright © 2014 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Acknowledgements Firstly I want to thank my supervisor Prof. M. J. Samways for his guidance and patience through the years and my co-supervisor Dr. R. Veldtman for his help the past few years. This project would not have been possible without the help of Prof. H. Geertsema, who helped me with the identification of the Lepidoptera and other insect caught in the study area. Also want to thank Dr. K. Oberlander for the help with the identification of the Oxalis species found in the study area and Flora Cameron from CREW with the identification of some of the special plants growing in the area. I further express my gratitude to Dr. Odette Curtis from the Overberg Renosterveld Project, who helped with the identification of the rare species found in the study area as well as information about grazing and burning of Renosterveld. -

Evolutionary History of Floral Key Innovations in Angiosperms Elisabeth Reyes

Evolutionary history of floral key innovations in angiosperms Elisabeth Reyes To cite this version: Elisabeth Reyes. Evolutionary history of floral key innovations in angiosperms. Botanics. Université Paris Saclay (COmUE), 2016. English. NNT : 2016SACLS489. tel-01443353 HAL Id: tel-01443353 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01443353 Submitted on 23 Jan 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. NNT : 2016SACLS489 THESE DE DOCTORAT DE L’UNIVERSITE PARIS-SACLAY, préparée à l’Université Paris-Sud ÉCOLE DOCTORALE N° 567 Sciences du Végétal : du Gène à l’Ecosystème Spécialité de Doctorat : Biologie Par Mme Elisabeth Reyes Evolutionary history of floral key innovations in angiosperms Thèse présentée et soutenue à Orsay, le 13 décembre 2016 : Composition du Jury : M. Ronse de Craene, Louis Directeur de recherche aux Jardins Rapporteur Botaniques Royaux d’Édimbourg M. Forest, Félix Directeur de recherche aux Jardins Rapporteur Botaniques Royaux de Kew Mme. Damerval, Catherine Directrice de recherche au Moulon Président du jury M. Lowry, Porter Curateur en chef aux Jardins Examinateur Botaniques du Missouri M. Haevermans, Thomas Maître de conférences au MNHN Examinateur Mme. Nadot, Sophie Professeur à l’Université Paris-Sud Directeur de thèse M. -

Some Medicinal Plants from Wild Flora of Romania and the Ecology

Research Journal of Agricultural Science, 44 (2), 2012 SOME MEDICINAL PLANTS FROM WILD FLORA OF ROMANIA AND THE ECOLOGY Helena Maria SABO Faculty of Psychology and Science of Education, UBB, Sindicatelor Street. No.7, Cluj-Napoca, Romania E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The importance of ecological factors for characteristic of central and Western Europe, medicinal species and their influence on active specific continental to the Eastern Europe, the principles synthesis and the specific uptake of presence of the Carpathian Mountains has an mineral elements from soil are presented. The impact on natural vegetation, and vegetation in the biological and ecological characters, the medicinal south has small Mediterranean influence. The importance, and the protection measurements for therapeutic use of medicinal plants is due to active some species are given. Ecological knowledge of principles they contain. For the plant body these medicinal plants has a double significance: on the substances meet have a metabolic role, such as one hand provides information on resorts where vitamins, enzymes, or the role of defense against medicinal plant species can be found to harvest and biological agents (insects, fungi, even vertebrates) use of them, on the other hand provides to chemical and physical stress (UV radiation), and information on conditions to be met by a possible in some cases still not precisely known functions of location of their culture. Lately several medicinal these substances for plants. As a result of research species were introduced into culture in order to on medicinal plants has been established that the ensure the raw materials of vegetable drug following factors influence ecology them: abiotic - industry. -

Colonial Garden Plants

COLONIAL GARD~J~ PLANTS I Flowers Before 1700 The following plants are listed according to the names most commonly used during the colonial period. The botanical name follows for accurate identification. The common name was listed first because many of the people using these lists will have access to or be familiar with that name rather than the botanical name. The botanical names are according to Bailey’s Hortus Second and The Standard Cyclopedia of Horticulture (3, 4). They are not the botanical names used during the colonial period for many of them have changed drastically. We have been very cautious concerning the interpretation of names to see that accuracy is maintained. By using several references spanning almost two hundred years (1, 3, 32, 35) we were able to interpret accurately the names of certain plants. For example, in the earliest works (32, 35), Lark’s Heel is used for Larkspur, also Delphinium. Then in later works the name Larkspur appears with the former in parenthesis. Similarly, the name "Emanies" appears frequently in the earliest books. Finally, one of them (35) lists the name Anemones as a synonym. Some of the names are amusing: "Issop" for Hyssop, "Pum- pions" for Pumpkins, "Mushmillions" for Muskmellons, "Isquou- terquashes" for Squashes, "Cowslips" for Primroses, "Daffadown dillies" for Daffodils. Other names are confusing. Bachelors Button was the name used for Gomphrena globosa, not for Centaurea cyanis as we use it today. Similarly, in the earliest literature, "Marygold" was used for Calendula. Later we begin to see "Pot Marygold" and "Calen- dula" for Calendula, and "Marygold" is reserved for Marigolds. -

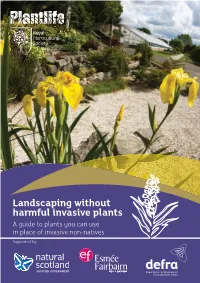

Landscaping Without Harmful Invasive Plants

Landscaping without harmful invasive plants A guide to plants you can use in place of invasive non-natives Supported by: This guide, produced by the wild plant conservation Landscaping charity Plantlife and the Royal Horticultural Society, can help you choose plants that are without less likely to cause problems to the environment harmful should they escape from your planting area. Even the most careful land managers cannot invasive ensure that their plants do not escape and plants establish in nearby habitats (as berries and seeds may be carried away by birds or the wind), so we hope you will fi nd this helpful. A few popular landscaping plants can cause problems for you / your clients and the environment. These are known as invasive non-native plants. Although they comprise a small Under the Wildlife and Countryside minority of the 70,000 or so plant varieties available, the Act, it is an offence to plant, or cause to damage they can do is extensive and may be irreversible. grow in the wild, a number of invasive ©Trevor Renals ©Trevor non-native plants. Government also has powers to ban the sale of invasive Some invasive non-native plants might be plants. At the time of producing this straightforward for you (or your clients) to keep in booklet there were no sales bans, but check if you can tend to the planted area often, but it is worth checking on the websites An unsuspecting sheep fl ounders in a in the wider countryside, where such management river. Invasive Floating Pennywort can below to fi nd the latest legislation is not feasible, these plants can establish and cause cause water to appear as solid ground.