Introduction Methods Results

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Native Orchid Society of South Australia

NATIVE ORCHID SOCIETY of SOUTH AUSTRALIA NATIVE ORCHID SOCIETY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA JOURNAL Volume 6, No. 10, November, 1982 Registered by Australia Post Publication No. SBH 1344. Price 40c PATRON: Mr T.R.N. Lothian PRESIDENT: Mr J.T. Simmons SECRETARY: Mr E.R. Hargreaves 4 Gothic Avenue 1 Halmon Avenue STONYFELL S.A. 5066 EVERARD PARK SA 5035 Telephone 32 5070 Telephone 293 2471 297 3724 VICE-PRESIDENT: Mr G.J. Nieuwenhoven COMMITTFE: Mr R. Shooter Mr P. Barnes TREASURER: Mr R.T. Robjohns Mrs A. Howe Mr R. Markwick EDITOR: Mr G.J. Nieuwenhoven NEXT MEETING WHEN: Tuesday, 23rd November, 1982 at 8.00 p.m. WHERE St. Matthews Hail, Bridge Street, Kensington. SUBJECT: This is our final meeting for 1982 and will take the form of a Social Evening. We will be showing a few slides to start the evening. Each member is requested to bring a plate. Tea, coffee, etc. will be provided. Plant Display and Commentary as usual, and Christmas raffle. NEW MEMBERS Mr. L. Field Mr. R.N. Pederson Mr. D. Unsworth Mrs. P.A. Biddiss Would all members please return any outstanding library books at the next meeting. FIELD TRIP -- CHANGE OF DATE AND VENUE The Field Trip to Peters Creek scheduled for 27th November, 1982, and announced in the last Journal has been cancelled. The extended dry season has not been conducive to flowering of the rarer moisture- loving Microtis spp., which were to be the objective of the trip. 92 FIELD TRIP - CHANGE OF DATE AND VENUE (Continued) Instead, an alternative trip has been arranged for Saturday afternoon, 4th December, 1982, meeting in Mount Compass at 2.00 p.m. -

Wattles of the City of Whittlesea

Wattles of the City of Whittlesea PROTECTING BIODIVERSITY ON PRIVATE LAND SERIES Wattles of the City of Whittlesea Over a dozen species of wattle are indigenous to the City of Whittlesea and many other wattle species are commonly grown in gardens. Most of the indigenous species are commonly found in the forested hills and the native forests in the northern parts of the municipality, with some species persisting along country roadsides, in smaller reserves and along creeks. Wattles are truly amazing • Wattles have multiple uses for Australian plants indigenous peoples, with most species used for food, medicine • There are more wattle species than and/or tools. any other plant genus in Australia • Wattle seeds have very hard coats (over 1000 species and subspecies). which mean they can survive in the • Wattles, like peas, fix nitrogen in ground for decades, waiting for a the soil, making them excellent cool fire to stimulate germination. for developing gardens and in • Australia’s floral emblem is a wattle: revegetation projects. Golden Wattle (Acacia pycnantha) • Many species of insects (including and this is one of Whittlesea’s local some butterflies) breed only on species specific species of wattles, making • In Victoria there is at least one them a central focus of biodiversity. wattle species in flower at all times • Wattle seeds and the insects of the year. In the Whittlesea attracted to wattle flowers are an area, there is an indigenous wattle important food source for most bird in flower from February to early species including Black Cockatoos December. and honeyeaters. Caterpillars of the Imperial Blue Butterfly are only found on wattles RB 3 Basic terminology • ‘Wattle’ = Acacia Wattle is the common name and Acacia the scientific name for this well-known group of similar / related species. -

List of Plants Observed and Identified by Members of the Ringwood Field Naturalists Club Inc

LIST OF PLANTS OBSERVED AND IDENTIFIED BY MEMBERS OF THE RINGWOOD FIELD NATURALISTS CLUB INC. ON THEIR SPRING FIELD TRIP TO YARRAM 16-18 NOVEMBER 2012 COMPILED BY JUDITH V COOKE Ninety Mile Beach 17 11 2012 1 Map of Yarram and surrounding places visited 16-18 11 2012 2 3 Botanical Name Common Name 16 17 18 11 11 11 ORCHIDS Caladenia carnea Pink Fingers F Caladenia gracilis Musky Caladenia F Caleana major Flying Duck Orchid F Calochilus campestris Copper Beard Orchid F Chiloglottis cornuta Little Bird Orchid F Chiloglottis valida Common Bird Orchid F Diuris sulphurea Hornet Orchid F F Microtis sp Onion Orchid F Stegostyla transitoria Eastern Bronze Caladenia F Thelymitra ixiodes Spotted Sun Orchid F Thelymitra media Tall Sun Orchid F 4 5 Botanical Name Common Name 16 17 18 11 11 11 FERNS Asplenium bulbiferum Mother Spleenwort Blechnum chambersii Lance Water Fern Blechnum fluviatile Ray Water Fern Blechnum nudum Fishbone Water Fern Blechnum patersonii Strap Water Fern Blechnum wattsii Hard Water Fern Calochlaena dubia Common Ground Fern Cyathea australis Rough Tree Fern Dicksonia antarctica Soft Tree Fern Grammitis billardieri Finger Fern Histiopteris incisa Batswing Fern Hymenophyllum cupressiforme Common Filmy Fern Hymenophyllum sp? Filmy Fern Hymenophyllum sp? Filmy/Bristle Fern Lastreopsis acuminata Shiny Shield Fern Microsorum diversifolium Kangaroo Fern Polystichum proliferum Mother Shield Fern Pteridium esculentum Austral Bracken Rumohra adiantiformis Shield Hare's-foot 6 Botanical Name Common Name 16 17 18 -

Cassytha Pubescens

Cassytha pubescens: Germination biology and interactions with native and introduced hosts Hong Tai (Steven), Tsang B.Sc. Hons (University of Adelaide) Thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Science School of Earth & Environmental Science University of Adelaide, Australia 03/05/2010 i Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................... ii Abstract .......................................................................................................................... v Declaration ................................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... viii Chapter. 1 Introduction .................................................................................................. 1 1.1 General Introduction ............................................................................................ 1 1.2 Literature Review ................................................................................................. 3 1.2.1 Characteristics of parasitic control agents .................................................... 3 1.2.2. Direct impacts on hosts ................................................................................ 7 1.2.3. Indirect impacts on hosts ............................................................................. 8 1.2.4. Summary ................................................................................................... -

Jervis Bay Territory Page 1 of 50 21-Jan-11 Species List for NRM Region (Blank), Jervis Bay Territory

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

Indigenous Plants of Bendigo

Produced by Indigenous Plants of Bendigo Indigenous Plants of Bendigo PMS 1807 RED PMS 432 GREY PMS 142 GOLD A Gardener’s Guide to Growing and Protecting Local Plants 3rd Edition 9 © Copyright City of Greater Bendigo and Bendigo Native Plant Group Inc. This work is Copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the City of Greater Bendigo. First Published 2004 Second Edition 2007 Third Edition 2013 Printed by Bendigo Modern Press: www.bmp.com.au This book is also available on the City of Greater Bendigo website: www.bendigo.vic.gov.au Printed on 100% recycled paper. Disclaimer “The information contained in this publication is of a general nature only. This publication is not intended to provide a definitive analysis, or discussion, on each issue canvassed. While the Committee/Council believes the information contained herein is correct, it does not accept any liability whatsoever/howsoever arising from reliance on this publication. Therefore, readers should make their own enquiries, and conduct their own investigations, concerning every issue canvassed herein.” Front cover - Clockwise from centre top: Bendigo Wax-flower (Pam Sheean), Hoary Sunray (Marilyn Sprague), Red Ironbark (Pam Sheean), Green Mallee (Anthony Sheean), Whirrakee Wattle (Anthony Sheean). Table of contents Acknowledgements ...............................................2 Foreword..........................................................3 Introduction.......................................................4 -

Phytophthora Resistance and Susceptibility Stock List

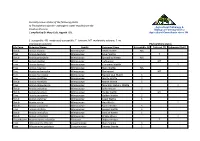

Currently known status of the following plants to Phytophthora species - pathogenic water moulds from the Agricultural Pathology & Kingdom Protista. Biological Farming Service C ompiled by Dr Mary Cole, Agpath P/L. Agricultural Consultants since 1980 S=susceptible; MS=moderately susceptible; T= tolerant; MT=moderately tolerant; ?=no information available. Phytophthora status Life Form Botanical Name Family Common Name Susceptible (S) Tolerant (T) Unknown (UnK) Shrub Acacia brownii Mimosaceae Heath Wattle MS Tree Acacia dealbata Mimosaceae Silver Wattle T Shrub Acacia genistifolia Mimosaceae Spreading Wattle MS Tree Acacia implexa Mimosaceae Lightwood MT Tree Acacia leprosa Mimosaceae Cinnamon Wattle ? Tree Acacia mearnsii Mimosaceae Black Wattle MS Tree Acacia melanoxylon Mimosaceae Blackwood MT Tree Acacia mucronata Mimosaceae Narrow Leaf Wattle S Tree Acacia myrtifolia Mimosaceae Myrtle Wattle S Shrub Acacia myrtifolia Mimosaceae Myrtle Wattle S Tree Acacia obliquinervia Mimosaceae Mountain Hickory Wattle ? Shrub Acacia oxycedrus Mimosaceae Spike Wattle S Shrub Acacia paradoxa Mimosaceae Hedge Wattle MT Tree Acacia pycnantha Mimosaceae Golden Wattle S Shrub Acacia sophorae Mimosaceae Coast Wattle S Shrub Acacia stricta Mimosaceae Hop Wattle ? Shrubs Acacia suaveolens Mimosaceae Sweet Wattle S Tree Acacia ulicifolia Mimosaceae Juniper Wattle S Shrub Acacia verniciflua Mimosaceae Varnish wattle S Shrub Acacia verticillata Mimosaceae Prickly Moses ? Groundcover Acaena novae-zelandiae Rosaceae Bidgee-Widgee T Tree Allocasuarina littoralis Casuarinaceae Black Sheoke S Tree Allocasuarina paludosa Casuarinaceae Swamp Sheoke S Tree Allocasuarina verticillata Casuarinaceae Drooping Sheoak S Sedge Amperea xipchoclada Euphorbaceae Broom Spurge S Grass Amphibromus neesii Poaceae Swamp Wallaby Grass ? Shrub Aotus ericoides Papillionaceae Common Aotus S Groundcover Apium prostratum Apiaceae Sea Celery MS Herb Arthropodium milleflorum Asparagaceae Pale Vanilla Lily S? Herb Arthropodium strictum Asparagaceae Chocolate Lily S? Shrub Atriplex paludosa ssp. -

ASBS Newsletter Will Recall That the Collaboration and Integration

Newsletter No. 174 March 2018 Price: $5.00 AUSTRALASIAN SYSTEMATIC BOTANY SOCIETY INCORPORATED Council President Vice President Darren Crayn Daniel Murphy Australian Tropical Herbarium (ATH) Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria James Cook University, Cairns Campus Birdwood Avenue PO Box 6811, Cairns Qld 4870 Melbourne, Vic. 3004 Australia Australia Tel: (+617)/(07) 4232 1859 Tel: (+613)/(03) 9252 2377 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Secretary Treasurer Jennifer Tate Matt Renner Institute of Fundamental Sciences Royal Botanic Garden Sydney Massey University Mrs Macquaries Road Private Bag 11222, Palmerston North 4442 Sydney NSW 2000 New Zealand Australia Tel: (+646)/(6) 356- 099 ext. 84718 Tel: (+61)/(0) 415 343 508 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Councillor Councillor Ryonen Butcher Heidi Meudt Western Australian Herbarium Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Locked Bag 104 PO Box 467, Cable St Bentley Delivery Centre WA 6983 Wellington 6140, New Zealand Australia Tel: (+644)/(4) 381 7127 Tel: (+618)/(08) 9219 9136 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Other constitutional bodies Hansjörg Eichler Research Committee Affiliate Society David Glenny Papua New Guinea Botanical Society Sarah Mathews Heidi Meudt Joanne Birch Advisory Standing Committees Katharina Schulte Financial Murray Henwood Patrick Brownsey Chair: Dan Murphy, Vice President, ex officio David Cantrill Grant application closing dates Bob Hill Hansjörg Eichler Research Fund: th th Ad hoc -

ACT, Australian Capital Territory

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

Post-Fire Recovery of Woody Plants in the New England Tableland Bioregion

Post-fire recovery of woody plants in the New England Tableland Bioregion Peter J. ClarkeA, Kirsten J. E. Knox, Monica L. Campbell and Lachlan M. Copeland Botany, School of Environmental and Rural Sciences, University of New England, Armidale, NSW 2351, AUSTRALIA. ACorresponding author; email: [email protected] Abstract: The resprouting response of plant species to fire is a key life history trait that has profound effects on post-fire population dynamics and community composition. This study documents the post-fire response (resprouting and maturation times) of woody species in six contrasting formations in the New England Tableland Bioregion of eastern Australia. Rainforest had the highest proportion of resprouting woody taxa and rocky outcrops had the lowest. Surprisingly, no significant difference in the median maturation length was found among habitats, but the communities varied in the range of maturation times. Within these communities, seedlings of species killed by fire, mature faster than seedlings of species that resprout. The slowest maturing species were those that have canopy held seed banks and were killed by fire, and these were used as indicator species to examine fire immaturity risk. Finally, we examine whether current fire management immaturity thresholds appear to be appropriate for these communities and find they need to be amended. Cunninghamia (2009) 11(2): 221–239 Introduction Maturation times of new recruits for those plants killed by fire is also a critical biological variable in the context of fire Fire is a pervasive ecological factor that influences the regimes because this time sets the lower limit for fire intervals evolution, distribution and abundance of woody plants that can cause local population decline or extirpation (Keith (Whelan 1995; Bond & van Wilgen 1996; Bradstock et al. -

King Island Flora: a Field Guide - 2014 Addendum

King Island Flora: A Field Guide - 2014 Addendum King Island Flora: A Field Guide – 2014 Addendum First published 2014 Copyright King Island Natural Resource Management Group Inc. Acknowledgements: The publication of this book has been coordinated by Nicholas Johannsohn, Graeme Batey, Margaret Batey, Eve Woolmore, Eva Finzel and Robyn Eades. Many thanks to Miguel De Salas, Mark Wapstra and Richard Schahinger for their technical advice. Text and editing: Nicholas Johannsohn, Eve Woolmore, Graeme Batey, Margaret Batey. Design: Nicholas Johannsohn Cover Image: Mark Wapstra Photographers are acknowledged in the text using the following initials – MW = Mark Wapstra MD = Manuel De Salas MB = Margaret Batey PC = Phil Collier Contents P 3 Introduction P 4 Corrections to 2002 Flora Guide P 5 New species name index New Species common name index P 6-8 Amendments to 2002 King Island Flora Guide taxa list, Recommended deletions, Subsumed into other taxa, Change of genus name P 9-13 New Species Profiles P 14 Bibliography Introduction It has been over ten years since the King Island Natural Resource Management Group published King Island Flora: A Field Guide. This addendum was created to incorporate newly listed species, genus name changes, subsumed species (i.e. incorporated into another genus), new subspecies and recommended deletions. It also provided the opportunity to correct mistakes identified in the original edition. The addendum also includes detailed profiles of ten of the newly identified species. Corrections to 2002 Edition Acacia Mucronata (variable sallow wattle p. 58) :Another common name for this species is Mountain Willow Gastrodia Species - There are very few collections of Gastrodia from King Island. -

Australian Orchidaceae: Genera and Species (12/1/2004)

AUSTRALIAN ORCHID NAME INDEX (21/1/2008) by Mark A. Clements Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research/Australian National Herbarium GPO Box 1600 Canberra ACT 2601 Australia Corresponding author: [email protected] INTRODUCTION The Australian Orchid Name Index (AONI) provides the currently accepted scientific names, together with their synonyms, of all Australian orchids including those in external territories. The appropriate scientific name for each orchid taxon is based on data published in the scientific or historical literature, and/or from study of the relevant type specimens or illustrations and study of taxa as herbarium specimens, in the field or in the living state. Structure of the index: Genera and species are listed alphabetically. Accepted names for taxa are in bold, followed by the author(s), place and date of publication, details of the type(s), including where it is held and assessment of its status. The institution(s) where type specimen(s) are housed are recorded using the international codes for Herbaria (Appendix 1) as listed in Holmgren et al’s Index Herbariorum (1981) continuously updated, see [http://sciweb.nybg.org/science2/IndexHerbariorum.asp]. Citation of authors follows Brummit & Powell (1992) Authors of Plant Names; for book abbreviations, the standard is Taxonomic Literature, 2nd edn. (Stafleu & Cowan 1976-88; supplements, 1992-2000); and periodicals are abbreviated according to B-P- H/S (Bridson, 1992) [http://www.ipni.org/index.html]. Synonyms are provided with relevant information on place of publication and details of the type(s). They are indented and listed in chronological order under the accepted taxon name. Synonyms are also cross-referenced under genus.