The Experience of Sickness and Health During Crusader Campaigns to the Eastern Mediterranean, 1095–1274

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William Historian of Malmesbury, of Crusade

William of Malmesbury, Historian of Crusade Rod Thomson University of Tasmania William of Malmesbury (c.1096 - c.1143), well known as one of the greatest historians of England, is not usually thought of as a historian of crusadingl His most famous work, the Gesta Regum Anglorum, in five books subdivided into 449 chapters, covers the history of England from the departure of the Romans until the early 1120s.2 But there are many digressions, most of them into Continental history; William is conscious of them and justifies them in explicit appeals to the reader. 3 Some provide necessary background to the course of English affairs, some are there for their entertainment value, and some because of their intrinsic importance. William's account of the First Crusade comes into the third category. It is the longest of all the diversions, occupying the last 46 of the 84 chapters which make up Book IV, or about 12% of the complete Gesta Regum. This is as long as a number of independent crusading chronicles (such as Fulcher's Gesta Francorum Iherosolimitanum Peregrinantium in its earliest edition, or the anonymous Gesta Francorum) and the story is brilliantly told. It follows the course of the Crusade from the Council of Clermont to the capture of Jerusalem, continuing with the so-called Crusade of H aI, and the deeds of the kings of Jerusalem and other great magnates such as Godfrey of Lorraine, Bohemond of Antioch, Raymond of Toulouse and Robert Curthose. The detailed narrative concludes in 1102; some scattered notices come down to c.1124, close to the writing of the Gesta, with a very little updating carried out in H34-5. -

Charters: What Survives?

Banner 4-final.qxp_Layout 1 01/11/2016 09:29 Page 1 Charters: what survives? Charters are our main source for twelh- and thirteenth-century Scotland. Most surviving charters were written for monasteries, which had many properties and privileges and gained considerable expertise in preserving their charters. However, many collections were lost when monasteries declined aer the Reformation (1560) and their lands passed to lay lords. Only 27% of Scottish charters from 1100–1250 survive as original single sheets of parchment; even fewer still have their seal attached. e remaining 73% exist only as later copies. Survival of charter collectionS (relating to 1100–1250) GEOGRAPHICAL SPREAD from inStitutionS founded by 1250 Our picture of documents in this period is geographically distorted. Some regions have no institutions with surviving charter collections, even as copies (like Galloway). Others had few if any monasteries, and so lacked large charter collections in the first place (like Caithness). Others are relatively well represented (like Fife). Survives Lost or unknown number of Surviving charterS CHRONOLOGICAL SPREAD (by earliest possible decade of creation) 400 Despite losses, the surviving documents point to a gradual increase Copies Originals in their use in the twelh century. 300 200 100 0 109 0s 110 0s 111 0s 112 0s 113 0s 114 0s 115 0s 116 0s 1170s 118 0s 119 0s 120 0s 121 0s 122 0s 123 0s 124 0s TYPES OF DONOR typeS of donor – Example of Melrose Abbey’s Charters It was common for monasteries to seek charters from those in Lay Lords Kings positions of authority in the kingdom: lay lords, kings and bishops. -

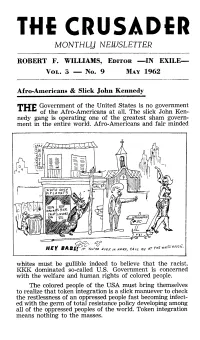

The Crusader Monthll,J Nelijsletter

THE CRUSADER MONTHLL,J NELIJSLETTER ROBERT F. WILLIAMS, EDITOR -IN EXILE- VoL . ~ - No. 9 MAY 1968 Afro-Americans & Slick John Kennedy Government of the United States is no government T~E of the Afro-Americans at all. The slick John Ken- nedy gang is operating one of the greatest sham govern- ment in the entire world. Afro-Americans and fair minded Od > ~- O THE wN«< /l~USL . lF Yov~Re EyER IN NE60, CALL ME AT whites must be gullible indeed to believe that the racist, KKK dominated so-called U.S. Government is concerned with the welfare and human rights of colored people. The colored people of the USA must bring themselves to realize that taken integration is a slick manuever to check the restlessness of an oppressed people fast becoming infect ed with the germ of total resistance policy developing among all of the oppressed peoples of the world. Token integration means nothing to the masses. Even an idiot should be able to see that so-called Token integration is no more than window dressing designed to lull the poor downtrodden Afro-American to sleep and to make the out side world think that the racist, savage USA is a fountainhead of social justice and democracy. The Afro-American in the USA is facing his greatest crisis since chattel slavery. All forms of violence and underhanded methods o.f extermination are being stepped up against our people. Contrary to what the "big daddies" and their "good nigras" would have us believe about all of the phoney progress they claim the race is making, the True status of the Afro-Ameri- can is s#eadily on the down turn. -

'The Conquest of the Holy Land by Saladin'

‘The Conquest of the Holy Land by Saladin’ This account of Saladin’s conquest of the Holy Land has come down to us in association with the Chronicon Anglicanum of Ralph of Coggeshall, a Cistercian from Essex who was one of the most important historians of early thirteenth-century England. However, while the author who compiled the tract may have been English, Ralph himself was not the person responsible. The particular value of this tract is that while in its present form it probably dates from c. 1220, it incorporates an earlier eye-witness account from a soldier who took part in the defence of Jerusalem and was wounded during the siege. The later compiler expanded this, adding details concerning the holy sites taken by the Muslims, quite possibly taken from a contemporary pilgrim guide, a brief account of the subsequent Third Crusade, which seems to have been taken from the much longer ‘Itinerary of King Richard’ by Richard de Templo, 1 and various passages of lamentation and moralising over the supposed iniquities of the Christians that had led God to allow the Muslims to succeed. The text has been translated from the De Expugnatione Terra Sanctae per Saladinum, in Ralph of Coggeshall, Chronicon Anglicanum, ed. J. Stevenson (Rolls Series, London 1875), 209-62. Use has been made of a previous translation of some passages from this tract by James Brundage, The Crusades: A Documentary History, (Milwaukee, 1962), 153-159, although the version here, which is a complete translation, and thus much fuller than the extracts used by Brundage, has been made afresh from the Latin text. -

The Crusader Coalition

The Crusader Coalition Crusading Rhetoric in the Islamic State's Magazines Dabiq and Rumiyah 31 July 2018 R. de Jager 411588 MA Global History and International Relations Erasmus University Rotterdam Supervisor: Prof. Dr. D. Douwes Second reader: Dr. R.J. Adriaansen The Crusader Coalition De Jager 411588 Table of Contents Abstract .................................................................................................................................. 3 A Note on Transliteration ........................................................................................................ 4 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 5 Chapter I: The Rise of the Islamic State ................................................................................ 16 Chapter II: The Terminology of the Radical Islamic Discourse ............................................. 22 Chapter III: The Crusades ..................................................................................................... 32 Chapter IV: The Crusades in Dabiq and Rumiyah ................................................................. 42 Chapter V: Conclusion .......................................................................................................... 72 Glossary ................................................................................................................................ 76 Bibliography ........................................................................................................................ -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2005/0250845 A1 Vermeersch Et Al

US 2005O250845A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2005/0250845 A1 Vermeersch et al. (43) Pub. Date: Nov. 10, 2005 (54) PSEUDOPOLYMORPHIC FORMS OF A HIV (86) PCT No.: PCT/EP03/50176 PROTEASE INHIBITOR (30) Foreign Application Priority Data (75) Inventors: Hans Wim Pieter Vermeersch, Gent (BE); Daniel Joseph Christiaan May 16, 2002 (EP)........................................ O2O76929.5 Thone, Beerse (BE); Luc Donne O O Marie-Louise Janssens, Malle (BE) Publication Classification Correspondence Address: (51) Int. Cl." ............................................ A61K 31/353 PHILIP S. JOHNSON (52) U.S. Cl. ............................................ 514/456; 549/396 JOHNSON & JOHNSON ONE JOHNSON & JOHNSON PLAZA NEW BRUNSWICK, NJ 08933-7003 (US) (57) ABSTRACT (73) Assignee: Tibotec Parmaceuticeals New pseudopolymorphic forms of (3R,3aS,6aR)-hexahy (21) Appl. No.: 10/514,352 drofuro2,3-blfuran-3-yl (1S,2R)-3-(4-aminophenyl)sul fonyl(isobutyl)amino-1-benzyl-2-hydroxypropylcarbam (22) PCT Fed: May 16, 2003 ate and processes for producing them are disclosed. Patent Application Publication Nov. 10, 2005 Sheet 1 of 18 US 2005/0250845 A1 E. i Patent Application Publication Nov. 10, 2005 Sheet 2 of 18 US 2005/0250845 A1 e Patent Application Publication Nov. 10, 2005 Sheet 3 of 18 US 2005/0250845 A1 Patent Application Publication Nov. 10, 2005 Sheet 4 of 18 US 2005/0250845 A1 92 NO C12S)-No S. C19 Se (Sb so woSC2 AS27 SN22 C23 Figure 4 Patent Application Publication Nov. 10, 2005 Sheet 5 of 18 US 2005/0250845 A1 -- 1800 1600 1400 1200 1000 800 soc wavenumbers (cm) Figure 5 - P1 : - P8'i P19 .. -

THE LOGISTICS of the FIRST CRUSADE 1095-1099 a Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Wester

FEEDING VICTORY: THE LOGISTICS OF THE FIRST CRUSADE 1095-1099 A Thesis presented to the faculty of the Graduate School of Western Carolina University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By William Donald O’Dell, Jr. Director: Dr. Vicki Szabo Associate Professor of Ancient and Medieval History History Department Committee Members: Dr. David Dorondo, History Dr. Robert Ferguson, History October, 2020 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my committee members and director for their assistance and encouragements. In particular, Dr. Vicki Szabo, without whose guidance and feedback this thesis would not exist, Dr. David Dorondo, whose guidance on the roles of logistics in cavalry warfare have helped shaped this thesis’ handling of such considerations and Dr. Robert Ferguson whose advice and recommendations for environmental historiography helped shaped my understanding on how such considerations influence every aspect of history, especially military logistics. I also offer my warmest regards and thanks to my parents, brothers, and extended family for their continued support. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ iv Abstract ............................................................................................................................................v Introduction ......................................................................................................................................1 -

Jewish Persecutions and Weather Shocks: 1100-1800⇤

Jewish Persecutions and Weather Shocks: 1100-1800⇤ § Robert Warren Anderson† Noel D. Johnson‡ Mark Koyama University of Michigan, Dearborn George Mason University George Mason University This Version: 30 December, 2013 Abstract What factors caused the persecution of minorities in medieval and early modern Europe? We build amodelthatpredictsthatminoritycommunitiesweremorelikelytobeexpropriatedinthewake of negative income shocks. Using panel data consisting of 1,366 city-level persecutions of Jews from 936 European cities between 1100 and 1800, we test whether persecutions were more likely in colder growing seasons. A one standard deviation decrease in average growing season temperature increased the probability of a persecution between one-half and one percentage points (relative to a baseline probability of two percent). This effect was strongest in regions with poor soil quality or located within weak states. We argue that long-run decline in violence against Jews between 1500 and 1800 is partly attributable to increases in fiscal and legal capacity across many European states. Key words: Political Economy; State Capacity; Expulsions; Jewish History; Climate JEL classification: N33; N43; Z12; J15; N53 ⇤We are grateful to Megan Teague and Michael Szpindor Watson for research assistance. We benefited from comments from Ran Abramitzky, Daron Acemoglu, Dean Phillip Bell, Pete Boettke, Tyler Cowen, Carmel Chiswick, Melissa Dell, Dan Bogart, Markus Eberhart, James Fenske, Joe Ferrie, Raphäel Franck, Avner Greif, Philip Hoffman, Larry Iannaccone, Remi Jedwab, Garett Jones, James Kai-sing Kung, Pete Leeson, Yannay Spitzer, Stelios Michalopoulos, Jean-Laurent Rosenthal, Naomi Lamoreaux, Jason Long, David Mitch, Joel Mokyr, Johanna Mollerstrom, Robin Mundill, Steven Nafziger, Jared Rubin, Gail Triner, John Wallis, Eugene White, Larry White, and Ekaterina Zhuravskaya. -

The Latin Principality of Antioch and Its Relationship with the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, 1188-1268 Samuel James Wilson

The Latin Principality of Antioch and Its Relationship with the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, 1188-1268 Samuel James Wilson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Nottingham Trent University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2016 1 Copyright Statement This work is the intellectual property of the author. You may copy up to 5% of this work for private study, or personal, non-commercial research. Any re-use of the information contained within this document should be fully referenced, quoting the author, title, university, degree level and pagination. Queries or requests for any other use, or if a more substantial copy is required, should be directed to the owner of the Intellectual Property Rights. 2 Abstract The Latin principality of Antioch was founded during the First Crusade (1095-1099), and survived for 170 years until its destruction by the Mamluks in 1268. This thesis offers the first full assessment of the thirteenth century principality of Antioch since the publication of Claude Cahen’s La Syrie du nord à l’époque des croisades et la principauté franque d’Antioche in 1940. It examines the Latin principality from its devastation by Saladin in 1188 until the fall of Antioch eighty years later, with a particular focus on its relationship with the Armenian kingdom of Cilicia. This thesis shows how the fate of the two states was closely intertwined for much of this period. The failure of the principality to recover from the major territorial losses it suffered in 1188 can be partly explained by the threat posed by the Cilician Armenians in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries. -

Marketing Fragment 6 X 10.Long.T65

Cambridge University Press 0521017475 - The Leper King and his Heirs: Baldwin IV and the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem Bernard Hamilton Index More information Index Abbasid caliphs of Baghdad, 80 Alexius II Comnenus, Byzantine emperor, al-Muqta®, 68 138, 148, 160, 174 al-Mustadi, 159 Alexius the protosebastus, 160 al-Nazir,159,171,184 Alfonso II, king of Aragon, 118 Abul' Khair, Baldwin IV's riding master, 28 Alice, princess of Antioch, 24, 41 Abu Shamah, historian, 17±18, 136 Alix of Lorraine, 140 Abu Sulayman Dawud, Baldwin IV's doctor, Almoravids of Majorca, 170 28, 251 Alwa, Nubian Christian kingdom of, 69 Acre, 46 n. 14, 53, 60, 119, 122, 127±8, 147, Amalric,kingofJerusalem,1,6,9,23±40, 192, 197, 203±4, 217±18, 223, 227, 243 43,45n.4,60,63±4,84±7,89±92, leprosaria, 257 95, 97, 107, 110, 116, 119±20, 125, 129, siege of (1189±91), 137, 196 n. 40, 231±2 149, 162, 173, 220, 249±51 Adam of St George of Labaene, 35 relations with Byzantium, 64±7, 111±13, Adela, queen of France, 30, 140, 149±50 127 Aden, 80, 182 relations with the kingdom of Sicily, 75±6, al-Adil, Saladin's brother, 87, 98, 141, 181, 81±2 183±4, 195, 201 relations with the Order of Assassins, 70±5 giraffe of, 202 Amalric of Nesle, Latin patriarch of al-Afdal, Saladin's son, 227±8 Jerusalem, 23, 35±6, 42, 114, 122, 133, Agnes of ChaÃtillon, queen of Hungary, 105 138±9, 144, 162 AgnesofCourtenay,2,9,23±6,33±4,84,89, Ambroise, Estoire de la guerre sainte,12 95±8,103±6,152±3,158,160,163, Andronicus Angelus, Byzantine envoy, 127, 167±8, 188, 194, 214 n. -

53Rd International Congress on Medieval Studies

53rd International Congress on Medieval Studies May 10–13, 2018 Medieval Institute College of Arts and Sciences Western Michigan University 1903 W. Michigan Ave. Kalamazoo, MI 49008-5432 wmich.edu/medieval 2018 i Table of Contents Welcome Letter iii Registration iv-v On-Campus Housing vi-vii Food viii-ix Travel x Driving and Parking xi Logistics and Amenities xii-xiii Varia xiv Off-Campus Accommodations vx Hotel Shuttle Routes xvi Hotel Shuttle Schedules xvii Campus Shuttles xviii Mailings xix Exhibits Hall xx Exhibitors xxi Plenary Lectures xxii Reception of the Classics in the Middle Ages Lecture xxiii Screenings xxiv Social Media xxv Advance Notice—2019 Congress xxvi The Congress: How It Works xxvii The Congress Academic Program xxviii-xxix Travel Awards xxx The Otto Gründler Book Prize xxxi Richard Rawlinson Center xxxii Center for Cistercian and Monastic Studies xxxiii M.A. Program in Medieval Studies xxxiv Medieval Institute Publications xxxv Endowment and Gift Funds xxxvi 2018 Congress Schedule of Events 1–192 Index of Sponsoring Organizations 193–198 Index of Participants 199–218 Floor Plans M-1 – M-9 List of Advertisers Advertising A-1 – A-36 Color Maps ii Dear colleagues, It’s a balmy 9 degrees here in Kalamazoo today, but I can’t complain—too much— because Kalamazoo will not feel the wrath of the “bomb cyclone” and polar vortex due to hit the East Coast later this week, the first week of 2018. Nonetheless, today in Kalamazoo, I long for spring and what it brings: the warmth of the weather, my colleagues and friends who will come in May to the International Congress on Medieval Studies. -

Crusades Volume 10, 2011

Crusades Volume 10, 2011 Published by AS H GATE for the Society for the Study of the Crusades and the Latin East The Illnesses of King Richard and King Philippe on the Third Crusade: An Understanding of arnaldia and leonardie Thomas Gregor Wagner (Uppsala University, Sweden; [email protected]) and Piers D. Mitchell (University of Cambridge; [email protected]) Introduction The crusade of King Richard I of England and Philippe Augustus 11of France was ill-fated. In 1191, after just a few days of intense fighting before the walls of Acre, both kings fell ill from an enigmatic illness known in Latin as arnaldia and in French as leonardie. For weeks both Richard and Philippe were close to the brink of death, before they finally recovered. In the summer of 1192 another epidemic struck the crusader army and Richard again became dangerously iIl- this time with a malady referred to asfebris emitritea. For nearly three months his condition was so serious that once again his men feared for his life. At this point Richard had to abandon his plan to capture the Christian holy sites, for Jerusalem was out of the reach of a king lying on a sickbed. After he had made peace with Saladin, Richard immediately returned to Haifa to receive medical treatment. He left the Holy Land in October 1192 and it is likely that his impaired health had been a major factor influencing his return to Europe at that time. The present article describes Richard and Philippe's crusade in terms of the diseases and the medical treatment received.