According to the Liber De Unitate Ecclesiae Conservanda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charters: What Survives?

Banner 4-final.qxp_Layout 1 01/11/2016 09:29 Page 1 Charters: what survives? Charters are our main source for twelh- and thirteenth-century Scotland. Most surviving charters were written for monasteries, which had many properties and privileges and gained considerable expertise in preserving their charters. However, many collections were lost when monasteries declined aer the Reformation (1560) and their lands passed to lay lords. Only 27% of Scottish charters from 1100–1250 survive as original single sheets of parchment; even fewer still have their seal attached. e remaining 73% exist only as later copies. Survival of charter collectionS (relating to 1100–1250) GEOGRAPHICAL SPREAD from inStitutionS founded by 1250 Our picture of documents in this period is geographically distorted. Some regions have no institutions with surviving charter collections, even as copies (like Galloway). Others had few if any monasteries, and so lacked large charter collections in the first place (like Caithness). Others are relatively well represented (like Fife). Survives Lost or unknown number of Surviving charterS CHRONOLOGICAL SPREAD (by earliest possible decade of creation) 400 Despite losses, the surviving documents point to a gradual increase Copies Originals in their use in the twelh century. 300 200 100 0 109 0s 110 0s 111 0s 112 0s 113 0s 114 0s 115 0s 116 0s 1170s 118 0s 119 0s 120 0s 121 0s 122 0s 123 0s 124 0s TYPES OF DONOR typeS of donor – Example of Melrose Abbey’s Charters It was common for monasteries to seek charters from those in Lay Lords Kings positions of authority in the kingdom: lay lords, kings and bishops. -

A File in the Online Version of the Kouroo Contexture (Approximately

SETTING THE SCENE FOR THOREAU’S POEM: YET AGAIN WE ATTEMPT TO LIVE AS ADAM 11th Century 1010s 1020s 1030s 1040s 1050s 1060s 1070s 1080s 1090s 12th Century 1110s 1120s 1130s 1140s 1150s 1160s 1170s 1180s 1190s 13th Century 1210s 1220s 1230s 1240s 1250s 1260s 1270s 1280s 1290s 14th Century 1310s 1320s 1330s 1340s 1350s 1360s 1370s 1380s 1390s 15th Century 1410s 1420s 1430s 1440s 1450s 1460s 1470s 1480s 1490s 16th Century 1510s 1520s 1530s 1540s 1550s 1560s 1570s 1580s 1590s 17th Century 1610s 1620s 1630s 1640s 1650s 1660s 1670s 1680s 1690s 18th Century 1710s 1720s 1730s 1740s 1750s 1760s 1770s 1780s 1790s 19th Century 1810s Alas! how little does the memory of these human inhabitants enhance the beauty of the landscape! Again, perhaps, Nature will try, with me for a first settler, and my house raised last spring to be the oldest in the hamlet. To be a Christian is to be Christ- like. VAUDÈS OF LYON 1600 William Gilbert, court physician to Queen Elizabeth, described the earth’s magnetism in DE MAGNETE. Robert Cawdrey’s A TREASURIE OR STORE-HOUSE OF SIMILES. Lord Mountjoy assumed control of Crown forces, garrisoned Ireland, and destroyed food stocks. O’Neill asked for help from Spain. HDT WHAT? INDEX 1600 1600 In about this year Robert Dudley, being interested in stories he had heard about the bottomlessness of Eldon Hole in Derbyshire, thought to test the matter. George Bradley, a serf, was lowered on the end of a lengthy rope. Dudley’s little experiment with another man’s existence did not result in the establishment of the fact that holes in the ground indeed did have bottoms; instead it became itself a source of legend as spinners would elaborate a just-so story according to which serf George was raving mad when hauled back to the surface, with hair turned white, and a few days later would succumb to the shock of it all. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2005/0250845 A1 Vermeersch Et Al

US 2005O250845A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2005/0250845 A1 Vermeersch et al. (43) Pub. Date: Nov. 10, 2005 (54) PSEUDOPOLYMORPHIC FORMS OF A HIV (86) PCT No.: PCT/EP03/50176 PROTEASE INHIBITOR (30) Foreign Application Priority Data (75) Inventors: Hans Wim Pieter Vermeersch, Gent (BE); Daniel Joseph Christiaan May 16, 2002 (EP)........................................ O2O76929.5 Thone, Beerse (BE); Luc Donne O O Marie-Louise Janssens, Malle (BE) Publication Classification Correspondence Address: (51) Int. Cl." ............................................ A61K 31/353 PHILIP S. JOHNSON (52) U.S. Cl. ............................................ 514/456; 549/396 JOHNSON & JOHNSON ONE JOHNSON & JOHNSON PLAZA NEW BRUNSWICK, NJ 08933-7003 (US) (57) ABSTRACT (73) Assignee: Tibotec Parmaceuticeals New pseudopolymorphic forms of (3R,3aS,6aR)-hexahy (21) Appl. No.: 10/514,352 drofuro2,3-blfuran-3-yl (1S,2R)-3-(4-aminophenyl)sul fonyl(isobutyl)amino-1-benzyl-2-hydroxypropylcarbam (22) PCT Fed: May 16, 2003 ate and processes for producing them are disclosed. Patent Application Publication Nov. 10, 2005 Sheet 1 of 18 US 2005/0250845 A1 E. i Patent Application Publication Nov. 10, 2005 Sheet 2 of 18 US 2005/0250845 A1 e Patent Application Publication Nov. 10, 2005 Sheet 3 of 18 US 2005/0250845 A1 Patent Application Publication Nov. 10, 2005 Sheet 4 of 18 US 2005/0250845 A1 92 NO C12S)-No S. C19 Se (Sb so woSC2 AS27 SN22 C23 Figure 4 Patent Application Publication Nov. 10, 2005 Sheet 5 of 18 US 2005/0250845 A1 -- 1800 1600 1400 1200 1000 800 soc wavenumbers (cm) Figure 5 - P1 : - P8'i P19 .. -

Jewish Persecutions and Weather Shocks: 1100-1800⇤

Jewish Persecutions and Weather Shocks: 1100-1800⇤ § Robert Warren Anderson† Noel D. Johnson‡ Mark Koyama University of Michigan, Dearborn George Mason University George Mason University This Version: 30 December, 2013 Abstract What factors caused the persecution of minorities in medieval and early modern Europe? We build amodelthatpredictsthatminoritycommunitiesweremorelikelytobeexpropriatedinthewake of negative income shocks. Using panel data consisting of 1,366 city-level persecutions of Jews from 936 European cities between 1100 and 1800, we test whether persecutions were more likely in colder growing seasons. A one standard deviation decrease in average growing season temperature increased the probability of a persecution between one-half and one percentage points (relative to a baseline probability of two percent). This effect was strongest in regions with poor soil quality or located within weak states. We argue that long-run decline in violence against Jews between 1500 and 1800 is partly attributable to increases in fiscal and legal capacity across many European states. Key words: Political Economy; State Capacity; Expulsions; Jewish History; Climate JEL classification: N33; N43; Z12; J15; N53 ⇤We are grateful to Megan Teague and Michael Szpindor Watson for research assistance. We benefited from comments from Ran Abramitzky, Daron Acemoglu, Dean Phillip Bell, Pete Boettke, Tyler Cowen, Carmel Chiswick, Melissa Dell, Dan Bogart, Markus Eberhart, James Fenske, Joe Ferrie, Raphäel Franck, Avner Greif, Philip Hoffman, Larry Iannaccone, Remi Jedwab, Garett Jones, James Kai-sing Kung, Pete Leeson, Yannay Spitzer, Stelios Michalopoulos, Jean-Laurent Rosenthal, Naomi Lamoreaux, Jason Long, David Mitch, Joel Mokyr, Johanna Mollerstrom, Robin Mundill, Steven Nafziger, Jared Rubin, Gail Triner, John Wallis, Eugene White, Larry White, and Ekaterina Zhuravskaya. -

Tower of London's 1,000 Year Old Facebook Timeline: List of Dates

Tower of London’s 1,000 year old Facebook timeline: list of dates View the timeline at www.facebook.com/toweroflondon Date Event Description 1066 First royal Having defeated the English at the Battle of fortress Hastings, William the conqueror builds a established Norman stronghold to keep hostile Londoners on site at bay. 1080s Work Work on the White Tower begins - and takes begins on about twenty years to complete. The stone the White tower becomes the tallest building in the Tower country, dominating the London skyline. 2 February Flambard Ranulf Flambard, chief tax-collector, is 1101 becomes imprisoned by King Henry I for extortion. He the first has a rope smuggled inside a barrel of wine, prisoner and climbs out of a window - whilst the and first drunken guards are asleep. escapee 1241 Earliest It is reported that a vision of St Thomas known Becket, Keeper of Works at the Tower before sighting of his murder in 1170, ‘appears’ to a priest during a ghost at the building of the inner curtain wall, the Tower apparently reducing the work to rubble by striking it with his cross. 1255 An elephant Henry III receives the Tower’s biggest animal joins the gift: a male African elephant from King Louis Royal IX of France. For over 600 years, strange and Menagerie exotic animals are sent as royal gifts and kept at the Tower of London, as symbols of foreign lands and political connections. 1275-79 Traitors’ Edward I builds St Thomas’ Tower and the Gate is built water gate known as Traitors’ Gate - famous for being the way into the Tower for those soon to be executed 1279 The Royal For nearly 600 years the nation’s coins are Mint moves mass produced on Mint Street at the Tower. -

The Christianization of the Dome of the Rock the Early Years of the Eleventh

CHAPTER FIVE THE CHRISTIANIZATION OF THE DOME OF THE ROCK The early years of the eleventh century have been described as the only period to witness official persecution of Jews and Christians by Muslims during Arab rule in Jerusalem.1 The Fatimid caliph Al-Hakim (996–1021), responsible for the persecution, terrorized Muslims as well. Al-Hakim, known to be deranged, called for the destruction of synagogues and churches, and had the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem razed in 1009.2 How- ever, one year before his death in 1021, this madman changed his attitude and allowed Jews and Christians to rebuild their churches and synagogues. The Jews did not find it easy to rebuild; even the Christians did not com- plete the reconstruction of the Holy Sepulcher until 1048, and then only with the help of Byzantine emperors.3 The destruction initiated by the mad caliph was cited by Pope Urban II decades later when, in 1096, he rallied his warring Frankish knights to avenge the “ruination” of the Christian altars by Muslims in the Holy Land. Though by the 1090s al-Hakim was long dead, and the Holy Sepulcher rebuilt and once again in Christian hands, Urban used the earlier events in service of his desire to quell the civil strife among the western knights. Some months after receiving a plea from Emperor Alexius I to help defend Byzantium from the Seljuk Turks, Urban called upon his knights to cease their greedy, internecine feuds and fight instead to regain control over the Holy Land—to remove the “pollution of paganism” that stained the holy city. -

Looking for Interpreter Zero: (14) the First Crusade & the Byzantine Story

Looking for Interpreter Zero: (14) The First Crusade & the Byzantine Story A body of interpreters & translators was active during the reign of Alexios I Komnenos', a ruler open to foreigners and diplomacy. Christine ADAMS. Published: April 16, 2017 Last updated: April 16, 2017 "Lord aid Sphenis, patrikios (patrician) and interpreter of the English."[1] After Alexios I Komnenos (reigned 1081-1118) seized power in Byzantium1081 he became involved in a series of negotiations, understandings and alliances as he sought to protect his land from depredations and conquest from all sides. His agreements with Normans and Turks in the 1080s can be read as a prelude to his most significant rapprochement: the embassy he sent to Pope Urban II in the spring of 1095 which led to the First Crusade. His manifest openness to foreigners and willingness to engage in the niceties of diplomacy characterised his turbulent reign. One reason for the Emperor’s open-mindedness could well be the fact that he was raised with a Turk – Tatikios - who was the son of one of his father’s captives. It may have been felt useful to provide him with some exposure to Turkish as it was expected that he would have contact with Turkish mercenaries later in life. It has even been suggested that for an emperor “not to have to rely on interpreters was obviously important”[2] but that was probably a minor consideration in a land that depended heavily on mercenaries and had a large immigrant community. The need to address foreigners was built into the structures of Byzantium. -

RESOLTECH 1080S Hardeners 1082, 1084, 1086 Highest Performance Epoxy Laminating & Infusion System

Technical Datasheet v3 - 14.04.2016 Previous version - 25.01.2016 RESOLTECH 1080S Hardeners 1082, 1084, 1086 Highest Performance Epoxy Laminating & Infusion System Highest modulus & rigidity epoxy system Adjustable pot life from 20min to 8h45min Room temperature mould release Final TG up to 114ºC RESOLTECH 1080S is the highest modulus epoxy system formulated by RESOLTECH to manufacture high performance, rigid, lightweight structures with glass, carbon, aramid and basalt fibres with or without post-curing. Using this novolac based epoxy resin will enable to reduce the amount of reinforcement fibre used, resulting in lighter, more rigid but also cheaper parts in spite of its higher price compared to more common Bisphenol A & F based resins. This new generation system, optimized with a low reactivity, low viscosity and excellent air release properties, is suitable for the manufacture any size structures and composite parts by hand layup, infusion and injection moulding while guaranteeing low toxicity working conditions to the user and ease of use thanks to its high wetting properties. It features an adjustable working time from 20min to 8h45min with its range of hardeners. It is possible to release the parts from the mould without post-curing. The maximum thermo mechanical properties of the laminate will be obtained after a post-curing cycle to obtain a final TG of 114ºC. Nevertheless, a post cure is not mandatory depending on the final use of the parts. The resulting structures will result in very rigid with high mechanical and the best interlaminar properties. RESOLTECH 1080S is recommended for the production of marine foils, secondary laminations of chain plates, production of lightweight & rigid skiffs or high performance kayaks & outriggers where the weight/rigidity is key. -

St Kenelm, St Melor and Anglo-Breton Contact from the Tenth to the Twelfth Centuries Caroline Brett

© The Author(s) 2020. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. St Kenelm, St Melor and Anglo-Breton contact from the tenth to the twelfth centuries Caroline Brett Abstract This article discusses the similarity between two apparently unrelated hagiographical texts: Vita et Miracula Kenelmi, composed between 1045 and the 1080s and attributed to Goscelin of Saint-Bertin, and Vita Melori, composed perhaps in the 1060s–1080s but surviving only in a variety of late-medieval versions from England and France. Kenelm was venerated at Winchcombe, Gloucestershire, Melor chiefly at Lanmeur, Finistère. Both saints were reputed to be royal child martyrs, and their Vitae contain a sequence of motifs and miracles so similar that a textual relationship or common oral origin seems a reasonable hypothesis. In order to elucidate this, possible contexts for the composition of Vita Melori are considered, and evidence for the Breton contacts of Goscelin and, earlier, Winchcombe Abbey is investigated. No priority of one Vita over the other can be demonstrated, but their relationship suggests that there was more cultural contact between western Brittany and England from the mid-tenth to the twelfth centuries than emerges overtly in the written record. Scholars of medieval hagiography seem so far to have overlooked an extraordi- nary similarity between the Latin Lives of two apparently unrelated saints. One is the Anglo-Saxon saint Kenelm, a Mercian prince who died c. -

Timeline-Castle-Acre-Priory.Pdf

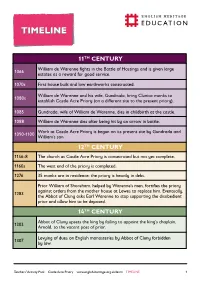

TIMELINETIMELINE 11TH CENTURY William de Warenne fights in the Battle of Hastings and is given large 1066 estates as a reward for good service. 1070s First house built and low earthworks constructed. William de Warenne and his wife, Gundrada, bring Cluniac monks to 1080s establish Castle Acre Priory (on a different site to the present priory). 1085 Gundrada, wife of William de Warenne, dies in childbirth at the castle. 1088 William de Warenne dies after being hit by an arrow in battle. Work at Castle Acre Priory is begun on its present site by Gundrada and 1090-1100 William’s son. 12TH CENTURY 1146-8 The church at Castle Acre Priory is consecrated but not yet complete. 1160s The west end of the priory is completed. 1276 35 monks are in residence: the priory is heavily in debt. Prior William of Shoreham, helped by Warenne’s men, fortifies the priory against orders from the mother house at Lewes to replace him. Eventually, 1283 the Abbot of Cluny asks Earl Warenne to stop supporting the disobedient prior and allow him to be deposed. 14TH CENTURY Abbot of Cluny upsets the king by failing to appoint the king’s chaplain, 1303 Arnold, to the vacant post of prior. Levying of dues on English monasteries by Abbot of Cluny forbidden 1307 by law. Teachers' Activity Pack Castle Acre Priory www.english-heritage.org.uk/learn TIMELINE 1 Renewed hostilities with France cause the English government to 1324 inspect Castle Acre to ensure it is not an ‘alien’ monastery (with French allegiances). 15TH CENTURY 1450 Community shrinking - 26 monks in residence. -

TEC-1090 Datasheet 5165B

Thermo Electric Cooling Temperature Controller TEC-1090 TEC Controller / Peltier Driver ±16 A / ±19 V OEM Precision TEC Controller General Description The TEC-1090 is a specialized TEC controller / power supply able to precision-drive Peltier elements. It features a true bipolar current source for cooling / heating, two temperature monitoring inputs (1x high precision, 1x auxiliary) and intelligent PID control with auto tuning. The TEC-1090 is fully digitally controlled, its hard- and firmware offer various communication and safety options. The included PC-Software allows configuration, control, monitoring and live diagnosis of the TEC controller via USB and RS485. All parameters are saved to non-volatile memory. Saving can be disabled for bus operation. For the most straightforward applications, only a power supply, a Peltier element and one temperature sensor Features need to be connected to the TEC-1090. After power-up the DC Input Voltage: 12 – 24 V nominal unit will operate according to pre-configured values. (In TEC Controller / Driver: Autonomous Operation stand-alone mode no control interface is needed.) Output Current: 0 to ±16 A, <1.5% Ripple The TEC-1090 can handle Pt100, Pt1000 or NTC (0 to ±10 A available as TEC-1089) temperature probes. For highest precision and stability Output Voltage: 0 to ±19 V (max. U IN - 3.5 V) applications a Pt1000 / 4-wire input configuration is Temp. Sensor Types: Pt100, Pt1000, NTC recommended. (Temperature acquisition circuitry of each Temperature Precision: <0.01 °C individual device is factory-calibrated to ensure optimal accuracy and repeatability.) Temperature Stability: <0.01 °C An auxiliary temperature input allows the connection of an Thermal Power Control: PID, Performance-optimized NTC probe that is located on the heat sink of the Peltier Configuration / Diagnosis: via USB / RS485 (Software) element. -

Biomaterials Science

1 Biomaterials 1 Science 5 PAPER 5 Biomaterial arrays with defined adhesion ligand 10 densities and matrix stiffness identify distinct 10 Cite this: DOI: 10.1039/c3bm60278h phenotypes for tumorigenic and non-tumorigenic Q1 human mesenchymal cell types 15 15 Tyler D. Hansen,†a Justin T. Koepsel,†a Ngoc Nhi Le,b Eric H. Nguyen,a Stefan Zorn,a Matthew Parlato,a Samuel G. Loveland,a Michael P. Schwartz*a and Q2 William L. Murphy*a,b,c 20 Here, we aimed to investigate migration of a model tumor cell line (HT-1080 fibrosarcoma cells, 20 HT-1080s) using synthetic biomaterials to systematically vary peptide ligand density and substrate stiffness. A range of substrate elastic moduli were investigated by using poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) hydro- gel arrays (0.34–17 kPa) and self-assembled monolayer (SAM) arrays (∼0.1–1 GPa), while cell adhesion was tuned by varying the presentation of Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD)-containing peptides. HT-1080 motility was 25 insensitive to cell adhesion ligand density on RGD-SAMs, as they migrated with similar speed and direc- 25 tionality for a wide range of RGD densities (0.2–5% mol fraction RGD). Similarly, HT-1080 migration speed was weakly dependent on adhesion on 0.34 kPa PEG surfaces. On 13 kPa surfaces, a sharp initial increase in cell speed was observed at low RGD concentration, with no further changes observed as RGD concentration was increased further. An increase in cell speed ∼two-fold for the 13 kPa relative to the 30 30 0.34 kPa PEG surface suggested an important role for substrate stiffness in mediating motility, which was confirmed for HT-1080s migrating on variable modulus PEG hydrogels with constant RGD concentration.