Twelfth Century Great Towers - the Case for the Defence - Richard Hulme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Castle Designs Through History: from Simple Mounds to Strong Towers

https://www.exploring-castles.com/castle_designs/ Castle Designs Through History: From Simple Mounds to Strong Towers Castle designs have changed over history. This is because of changes in technology over time – as well as changes to the function and purpose of castles. The first castles were simply ‘mounds’ of earth, and medieval castle designs improved on these basics – adding ditches in the Motte & Bailey design. As technology advanced – and as attackers got more sophisticated – elaborate concentric castle designs emerged, creating a fortress almost impregnable to its enemies. Nowadays, castles are designed for prestige, for fantasy, and to embellish a romantic view of the life of kings, queens and nobles from years gone by. This page gives a brief overview of the history of castles, and explains why different castle designs came about. Fundamentally, these changing designs were due to the changes in the purpose and significance of castles. Early Medieval Times From Norman Times: Motte & Bailey Castles – Simple designs that were quick to build The first castles, built in the Early Middle Ages (early Medieval period), were ‘earthworks’ – mounds of earth primarily built for defence, as enemies struggled to climb them. During the 1000s, the Normans developed these into Motte and Bailey castle designs. Effectively, a ‘Motte’ was a large mound of earth, and a ‘Bailey’ was the flattened area beside the mound. The ‘Motte’ could be surrounded with a ditch, and buildings could be placed on the bailey – made of timber or, if time permitted, stone. The key benefit of Motte & Bailey castles was that they were very quick to build, but pretty difficult to attack. -

Our Castle, Our Town

Our Castle, Our Town An n 2011 BACAS took part in a community project undertaken by Castle Cary investigation Museum with the purpose of exploring a selection of historic sites in and around into the the town of Castle Cary. archaeology of I Castle Cary's Using a number of non intrusive surveying methods including geophysical survey Castle site and aerial photography, the aim of the project was to develop the interpretation of some of the town’s historic sites, including the town’s castle site. A geophysical Matthew survey was undertaken at three sites, including the Castle site, the later manorial Charlton site, and a small survey 2 km south west of Castle Cary, at Dimmer. The focus of the article will be the main castle site centred in the town (see Figure 1) which will provide a brief history of the site, followed by the results of the survey and subsequent interpretation. Location and Topography Castle Cary is a small town in south east Somerset, lying within the Jurassic belt of geology, approximately at the junction of the upper lias and the inferior and upper oolites. Building stone is plentiful, and is orange to yellow in colour. This is the source of the River Cary, which now runs to the Bristol Channel via King’s Sedgemoor Drain and the River Parrett, but prior to 1793 petered out within Sedgemoor. The site occupies a natural spur formed by two conjoining, irregularly shaped mounds extending from the north east to the south west. The ground gradually rises to the north and, more steeply, to the east, and falls away to the south. -

Shell Keeps-Catalogue1

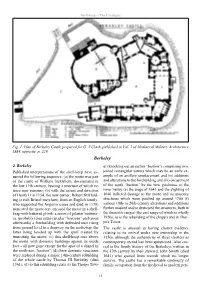

Shell-keeps - The Catalogue Fig. 1. Plan of Berkeley Castle prepared for G. T Clark, published in Vol. 1 of Mediaeval Military Architecture, 1884, opposite. p. 229. Berkeley 2. Berkeley er (knocking out an earlier “bastion”) comprising two, Published interpretations of the shell-keep have as- joined rectangular towers which may be an early ex- sumed the following sequence: (a) the motte was part ample of an artillery emplacement and (ii) additions of the castle of William fitzOsbern, documented in and alterations to the forebuilding and (iii) encasement the late 11th century, bearing a structure of which no of the south “bastion” by the new gatehouse to the trace now remains; (b) with the assent and direction inner bailey (e) the siege of 1645 and the slighting of of Henry II in 1154, the new owner, Robert fitzHard- 1646 inflicted damage to the motte and its masonry ing (a rich Bristol merchant, from an English family, structures which were patched up around 1700 (f) who supported the Angevin cause and died in 1170) various 18th- to 20th-century alterations and additions truncated the motte-top, encased the motte in a shell- further masked and/or destroyed the structures, both in keep with battered plinth, a series of pilaster buttress- the domestic ranges (the east range of which is wholly es, (probably) four semi-circular “bastions” and (soon 1920s, as is the rebuilding of the chapel) and in Thor- afterwards) a forebuilding with defended stair rising pe's Tower. from ground level to a doorway on the motte-top, the The castle is unusual in having charter evidence latter being leveled up with the spoil created by relating to its revival under new ownership in the truncating the motte; (c) this shell-keep rose above 1150s, although the authenticity of these charters as the motte, with domestic buildings against its inside contemporary record has been questioned. -

Gloucestershire Castles

Gloucestershire Archives Take One Castle Gloucestershire Castles The first castles in Gloucestershire were built soon after the Norman invasion of 1066. After the Battle of Hastings, the Normans had an urgent need to consolidate the land they had conquered and at the same time provide a secure political and military base to control the country. Castles were an ideal way to do this as not only did they secure newly won lands in military terms (acting as bases for troops and supply bases), they also served as a visible reminder to the local population of the ever-present power and threat of force of their new overlords. Early castles were usually one of three types; a ringwork, a motte or a motte & bailey; A Ringwork was a simple oval or circular earthwork formed of a ditch and bank. A motte was an artificially raised earthwork (made by piling up turf and soil) with a flat top on which was built a wooden tower or ‘keep’ and a protective palisade. A motte & bailey was a combination of a motte with a bailey or walled enclosure that usually but not always enclosed the motte. The keep was the strongest and securest part of a castle and was usually the main place of residence of the lord of the castle, although this changed over time. The name has a complex origin and stems from the Middle English term ‘kype’, meaning basket or cask, after the structure of the early keeps (which resembled tubes). The name ‘keep’ was only used from the 1500s onwards and the contemporary medieval term was ‘donjon’ (an apparent French corruption of the Latin dominarium) although turris, turris castri or magna turris (tower, castle tower and great tower respectively) were also used. -

An Excavation in the Inner Bailey of Shrewsbury Castle

An excavation in the inner bailey of Shrewsbury Castle Nigel Baker January 2020 An excavation in the inner bailey of Shrewsbury Castle Nigel Baker BA PhD FSA MCIfA January 2020 A report to the Castle Studies Trust 1. Shrewsbury Castle: the inner bailey excavation in progress, July 2019. North to top. (Shropshire Council) Summary In May and July 2019 a two-phase archaeological investigation of the inner bailey of Shrewsbury Castle took place, supported by a grant from the Castle Studies Trust. A geophysical survey by Tiger Geo used resistivity and ground-penetrating radar to identify a hard surface under the north-west side of the inner bailey lawn and a number of features under the western rampart. A trench excavated across the lawn showed that the hard material was the flattened top of natural glacial deposits, the site having been levelled in the post-medieval period, possibly by Telford in the 1790s. The natural gravel was found to have been cut by a twelve-metre wide ditch around the base of the motte, together with pits and garden features. One pit was of late pre-Conquest date. 1 Introduction Shrewsbury Castle is situated on the isthmus, the neck, of the great loop of the river Severn containing the pre-Conquest borough of Shrewsbury, a situation akin to that of the castles at Durham and Bristol. It was in existence within three years of the Battle of Hastings and in 1069 withstood a siege mounted by local rebels against Norman rule under Edric ‘the Wild’ (Sylvaticus). It is one of the best-preserved Conquest-period shire-town earthwork castles in England, but is also one of the least well known, no excavation having previously taken place within the perimeter of the inner bailey. -

Charters: What Survives?

Banner 4-final.qxp_Layout 1 01/11/2016 09:29 Page 1 Charters: what survives? Charters are our main source for twelh- and thirteenth-century Scotland. Most surviving charters were written for monasteries, which had many properties and privileges and gained considerable expertise in preserving their charters. However, many collections were lost when monasteries declined aer the Reformation (1560) and their lands passed to lay lords. Only 27% of Scottish charters from 1100–1250 survive as original single sheets of parchment; even fewer still have their seal attached. e remaining 73% exist only as later copies. Survival of charter collectionS (relating to 1100–1250) GEOGRAPHICAL SPREAD from inStitutionS founded by 1250 Our picture of documents in this period is geographically distorted. Some regions have no institutions with surviving charter collections, even as copies (like Galloway). Others had few if any monasteries, and so lacked large charter collections in the first place (like Caithness). Others are relatively well represented (like Fife). Survives Lost or unknown number of Surviving charterS CHRONOLOGICAL SPREAD (by earliest possible decade of creation) 400 Despite losses, the surviving documents point to a gradual increase Copies Originals in their use in the twelh century. 300 200 100 0 109 0s 110 0s 111 0s 112 0s 113 0s 114 0s 115 0s 116 0s 1170s 118 0s 119 0s 120 0s 121 0s 122 0s 123 0s 124 0s TYPES OF DONOR typeS of donor – Example of Melrose Abbey’s Charters It was common for monasteries to seek charters from those in Lay Lords Kings positions of authority in the kingdom: lay lords, kings and bishops. -

A File in the Online Version of the Kouroo Contexture (Approximately

SETTING THE SCENE FOR THOREAU’S POEM: YET AGAIN WE ATTEMPT TO LIVE AS ADAM 11th Century 1010s 1020s 1030s 1040s 1050s 1060s 1070s 1080s 1090s 12th Century 1110s 1120s 1130s 1140s 1150s 1160s 1170s 1180s 1190s 13th Century 1210s 1220s 1230s 1240s 1250s 1260s 1270s 1280s 1290s 14th Century 1310s 1320s 1330s 1340s 1350s 1360s 1370s 1380s 1390s 15th Century 1410s 1420s 1430s 1440s 1450s 1460s 1470s 1480s 1490s 16th Century 1510s 1520s 1530s 1540s 1550s 1560s 1570s 1580s 1590s 17th Century 1610s 1620s 1630s 1640s 1650s 1660s 1670s 1680s 1690s 18th Century 1710s 1720s 1730s 1740s 1750s 1760s 1770s 1780s 1790s 19th Century 1810s Alas! how little does the memory of these human inhabitants enhance the beauty of the landscape! Again, perhaps, Nature will try, with me for a first settler, and my house raised last spring to be the oldest in the hamlet. To be a Christian is to be Christ- like. VAUDÈS OF LYON 1600 William Gilbert, court physician to Queen Elizabeth, described the earth’s magnetism in DE MAGNETE. Robert Cawdrey’s A TREASURIE OR STORE-HOUSE OF SIMILES. Lord Mountjoy assumed control of Crown forces, garrisoned Ireland, and destroyed food stocks. O’Neill asked for help from Spain. HDT WHAT? INDEX 1600 1600 In about this year Robert Dudley, being interested in stories he had heard about the bottomlessness of Eldon Hole in Derbyshire, thought to test the matter. George Bradley, a serf, was lowered on the end of a lengthy rope. Dudley’s little experiment with another man’s existence did not result in the establishment of the fact that holes in the ground indeed did have bottoms; instead it became itself a source of legend as spinners would elaborate a just-so story according to which serf George was raving mad when hauled back to the surface, with hair turned white, and a few days later would succumb to the shock of it all. -

VWR Circulators and Chillers

VWR Circulators and Chillers Superior Temperature Control Equipment Clockwise from top left: 13721-200, 13721-172, 13721-138, 13721-082 Controllers Table of Contents. Page Product Features. 2-3 Precise Controllers Controllers . 4-5 Choice of four controllers. From state-of-the-art program- VWR Signature` mable designs that provide Refrigerated/Heating ultimate control, to the analog Circulating Baths. 6-10 design that is perfect for less demanding applications. How To Choose A Chiller . 11 VWR Signature Recirculating Chillers . 12-13 VWR Signature Heating Immersion Circulator. 14 Durable Design VWR` Open Bath Systems . 15 Immersed parts and reservoirs are made of corrosion-fighting VWR Signature stainless steel. The exterior Heating Circulating Baths . 16-17 surface is a tough powder coating for easy clean-up. VWR Refrigerated/Heating Circulating Baths. 18-21 VWR Immersion & Flow-Through Coolers . 22 VWR Ambient Bath Cooler. 22 Double Safety VWR Heating Recirculator . 22 Your equipment and work are protected with redundant over VWR Heating Immersion Circulators . 23 temperature and low liquid cutoff standard on all circula- VWR Heating Circulating Baths . 24-25 tors. 60Hz models are CSA approved, 50Hz models carry Accessories . 26 the CE mark. At-a-Glance Chart . 27 Environmentally Responsible VWR Refrigerated Circulators and Chillers use R-134a refrigerant, and no ozone- depleting CFC’s are used in the manufacturing process. All instruments are manufactured in an ISO 9001 accredited facility. 2 To order, call 1-800-932-5000 or visit vwr.com Controllers Time Savers Advanced refrigeration sys- tems and high wattage heaters respond quickly to temperature changes. You'll have minimum waiting time for your circulator to stabilize. -

Shell Keeps at Carmarthen Castle and Berkeley Castle

Fig. 1. A bird's-eye view of Windsor Castle in 1658, by Wenceslaus Hollar (detail). Within the shell-keep are 14th century ranges. From the University of Toronto Wenceslaus Hollar Digital Collection. Reproduced with thanks. Shell-keeps revisited: the bailey on the motte? Robert Higham, BA, PhD, FSA, FRHistS Honorary Fellow, University of Exeter Dedicated to Jo Cox and John Thorp, who revived my interest in this subject at Berkeley Castle Design and illustrations assembled by Neil Guy Published by the Castle Studies Group. © Text: Robert Higham Shell-keeps re-visited: the bailey on the motte? 1 Revision 19 - 05/11/2015 Fig. 2. Lincoln Castle, Lucy Tower, following recent refurbishment. Image: Neil Guy. Abstract Scholarly attention was first paid to the sorts of castle ● that multi-lobed towers built on motte-tops discussed here in the later 18th century. The “shell- should be seen as a separate form; that truly keep” as a particular category has been accepted in circular forms (not on mottes) should be seen as a academic discussion since its promotion as a medieval separate form; design by G.T. Clark in the later 19th century. Major ● that the term “shell-keep” should be reserved for works on castles by Ella Armitage and A. Hamilton mottes with structures built against or integrated Thompson (both in 1912) made interesting observa- with their surrounding wall so as to leave an open, tions on shell-keeps. St John Hope published Windsor central space with inward-looking accommodation; Castle, which has a major example of the type, a year later (1913). -

Tower of London's 1,000 Year Old Facebook Timeline: List of Dates

Tower of London’s 1,000 year old Facebook timeline: list of dates View the timeline at www.facebook.com/toweroflondon Date Event Description 1066 First royal Having defeated the English at the Battle of fortress Hastings, William the conqueror builds a established Norman stronghold to keep hostile Londoners on site at bay. 1080s Work Work on the White Tower begins - and takes begins on about twenty years to complete. The stone the White tower becomes the tallest building in the Tower country, dominating the London skyline. 2 February Flambard Ranulf Flambard, chief tax-collector, is 1101 becomes imprisoned by King Henry I for extortion. He the first has a rope smuggled inside a barrel of wine, prisoner and climbs out of a window - whilst the and first drunken guards are asleep. escapee 1241 Earliest It is reported that a vision of St Thomas known Becket, Keeper of Works at the Tower before sighting of his murder in 1170, ‘appears’ to a priest during a ghost at the building of the inner curtain wall, the Tower apparently reducing the work to rubble by striking it with his cross. 1255 An elephant Henry III receives the Tower’s biggest animal joins the gift: a male African elephant from King Louis Royal IX of France. For over 600 years, strange and Menagerie exotic animals are sent as royal gifts and kept at the Tower of London, as symbols of foreign lands and political connections. 1275-79 Traitors’ Edward I builds St Thomas’ Tower and the Gate is built water gate known as Traitors’ Gate - famous for being the way into the Tower for those soon to be executed 1279 The Royal For nearly 600 years the nation’s coins are Mint moves mass produced on Mint Street at the Tower. -

Portchester Castle Student Activity Sheets

STUDENT ACTIVITY SHEETS Portchester Castle This resource has been designed to help students step into the story of Portchester Castle, which provides essential insight into over 1,700 years of history. It was a Roman fort, a Saxon stronghold, a royal castle and eventually a prison. Give these activity sheets to students on site to help them explore Portchester Castle. Get in touch with our Education Booking Team: 0370 333 0606 [email protected] https://bookings.english-heritage.org.uk/education Don’t forget to download our Hazard Information Sheets and Discovery Visit Risk Assessments to help with planning: • In the Footsteps of Kings • Big History: From Dominant Castle to Hidden Fort Share your visit with us @EHEducation The English Heritage Trust is a charity, no. 1140351, and a company, no. 07447221, registered in England. All images are copyright of English Heritage or Historic England unless otherwise stated. Published July 2017 Portchester Castle is over 1,700 years old! It was a Roman fort, a Saxon stronghold, a royal palace and eventually a prison. Its commanding location means it has played a major part in defending Portsmouth Harbour EXPLORE and the Solent for hundreds of years. THE CASTLE DISCOVER OUR TOP 10 Explore the castle in small groups. THINGS TO SEE Complete the challenges to find out about Portchester’s exciting past. 1 ROMAN WALLS These walls were built between AD 285 and 290 by a Roman naval commander called Carausius. He was in charge of protecting this bit of the coast from pirate attacks. The walls’ core is made from layers of flint, bonded together with mortar. -

Town Guide 2020

FREE SHREWSBURY TOWN GUIDE 2020 originalshrewsbury.co.uk Top - bottom: Theatre Severn, Wyle Cop, Charles Darwin and Mary Webb statues in School Gardens, Butcher Row, The Square, Quarry Park, St Chad’s Church, Sabrina Boat. WELCOME Shrewsbury loves people and we hope the feeling is Arrive 5 mutual. You can easily explore the town centre on foot, bike or boat and discover plenty along the way. It’s Discover 7 not just a place full of flowers, medieval passages and café culture, Shrewsbury is packed with independent Eat 11 and national shops, restaurants and bars as well as must-visit international festivals. Drink 15 If you need more information call the Visitor Shop 19 Information Centre on 01743 258888, pop into it’s office in the Shrewsbury Museum and Art Gallery or ask Map 24 one of the Shrewsbury Ambassadors you’ll see around town from Easter until August . Events 27 YOU CAN’T COPY SHREWSBURY Explore 29 Do 33 Enjoy 36 Roam 39 48 Hours 42 Stay 45 For more information visit orginalshrewsbury.co.uk & visitshropshire.co.uk ORIGINAL SHREWSBURY AMBASSADORS From 11th April until late September visitors to Shrewsbury can discover the full range of what the town has to offer thanks to our team of Ambassadors. The Ambassadors, introduced in 2019, work alongside the Shrewsbury Town Guides and help visitors discover the hidden gems in the town. Ambassadors are on duty on them at points throughout the town Saturdays and Sundays from 10am and they can be spotted wearing to 2pm. Their aim is provide a better their bright blue tops and a experience for visitors and to help welcoming smile! them make the most of all that You can also volunteer by going to the Shrewsbury has to offer.