The Eucharist in Twelfth-Century Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Antiphonary of Bangor and Its Musical Implications

The Antiphonary of Bangor and its Musical Implications by Helen Patterson A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto © Copyright by Helen Patterson 2013 The Antiphonary of Bangor and its Musical Implications Helen Patterson Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto 2013 Abstract This dissertation examines the hymns of the Antiphonary of Bangor (AB) (Antiphonarium Benchorense, Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana C. 5 inf.) and considers its musical implications in medieval Ireland. Neither an antiphonary in the true sense, with chants and verses for the Office, nor a book with the complete texts for the liturgy, the AB is a unique Irish manuscript. Dated from the late seventh-century, the AB is a collection of Latin hymns, prayers and texts attributed to the monastic community of Bangor in Northern Ireland. Given the scarcity of information pertaining to music in early Ireland, the AB is invaluable for its literary insights. Studied by liturgical, medieval, and Celtic scholars, and acknowledged as one of the few surviving sources of the Irish church, the manuscript reflects the influence of the wider Christian world. The hymns in particular show that this form of poetical expression was significant in early Christian Ireland and have made a contribution to the corpus of Latin literature. Prompted by an earlier hypothesis that the AB was a type of choirbook, the chapters move from these texts to consider the monastery of Bangor and the cultural context from which the manuscript emerges. As the Irish peregrini are known to have had an impact on the continent, and the AB was recovered in ii Bobbio, Italy, it is important to recognize the hymns not only in terms of monastic development, but what they reveal about music. -

An Early Turning Point in the History of the Crusades

Jonathan Phillips. The Second Crusade: Extending the Frontiers of Christendom. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007. xxix + 364 pp. $40.00, cloth, ISBN 978-0-300-11274-0. Reviewed by Jonathan R. Lyon Published on H-German (March, 2008) As the author makes clear in the excellent in‐ cepts could be employed against a variety of Latin troduction to this work, the Second Crusade Christendom's enemies. (1145-49) has typically not attracted as much in‐ Phillips divides his work into fourteen terest from modern historians as the more fa‐ chronologically-arranged chapters, although sepa‐ mous First Crusade (1095-99) and Third Crusade rate chapters treat the Iberian and Baltic compo‐ (1188-92). A key explanation for this trend is the nents of the crusade. The frst two chapters dis‐ Second Crusade's failure to make any significant cuss the period between the First and the Second gains for the Christians of the Holy Land in the Crusade; chapter 1 focuses on the various pilgrim‐ wake of the Muslim conquest of Edessa in 1144. ages and crusading efforts of the early twelfth Nevertheless, as Phillips convincingly argues, this century, and chapter 2 provides a rich, fascinating crusade--despite its lack of success--demands discussion of the powerful legacy the First Cru‐ more attention than it has received for several sade left to Latin Christian culture in the decades reasons. It was the frst crusade to the Holy Land after 1099. Phillips persuasively argues that this to involve western European kings and thus legacy had a significant impact on recruiting for forced rulers to consider the consequences of the Second Crusade, because the generation of leaving their kingdoms for months (if not years) young nobles alive in the 1140s had grown up at a time. -

Personal Names and Denomination of Livonians in Early Written Sources

ESUKA – JEFUL 2014, 5–1: 13–26 PERSONAL NAMES AND DENOMINATION OF LIVONIANS IN EARLY WRITTEN SOURCES Enn Ernits Estonian University of Life Sciences Abstract. This paper presents the timeline of ethnonyms denoting Livonians; specifies their chronology; and analyses the names used for this ethnos and possible personal names. If we consider the dating of the event, the earliest sources mentioning Livonians are Gesta Danorum and the Tale of Bygone Years (both 10th century), but both sources present rather dubious information: in the first the battle of Bråvalla itself or the date are dubious (6th, 8th or 10th century); in the latter we cannot be sure that the member of the Rus delegation was really a Livonian. If we consider the time of recording, the earliest sources are two rune inscriptions from Sweden (11th century), and the next is the list of neighbouring peoples of the Russians from the Tale of Bygone Years (12th century). The personal names Bicco and Ger referred in Gesta Danorum, and Либи Аръфастовъ in Tale of Bygone Years are very problematic. The first certain personal name of a Livonian is *Mustakka, *Mustukka or *Mustoikka (from Finnic *musta ‘black’) written in 1040–1050s on a strip of birch bark in Novgorod. Keywords: Livs, Finnic peoples, ethnonyms, anthroponyms, onomastics DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12697/jeful.2014.5.1.01 1. Introduction This paper (1) seeks to present the timeline of ethnonyms denoting Livonians; (2) to specify their chronology; (3) and to analyse the names used for this ethnos and possible personal names. It is supple- mental to the paper by Mauno Koski on words denoting Livonians (Koski 2011). -

Charters: What Survives?

Banner 4-final.qxp_Layout 1 01/11/2016 09:29 Page 1 Charters: what survives? Charters are our main source for twelh- and thirteenth-century Scotland. Most surviving charters were written for monasteries, which had many properties and privileges and gained considerable expertise in preserving their charters. However, many collections were lost when monasteries declined aer the Reformation (1560) and their lands passed to lay lords. Only 27% of Scottish charters from 1100–1250 survive as original single sheets of parchment; even fewer still have their seal attached. e remaining 73% exist only as later copies. Survival of charter collectionS (relating to 1100–1250) GEOGRAPHICAL SPREAD from inStitutionS founded by 1250 Our picture of documents in this period is geographically distorted. Some regions have no institutions with surviving charter collections, even as copies (like Galloway). Others had few if any monasteries, and so lacked large charter collections in the first place (like Caithness). Others are relatively well represented (like Fife). Survives Lost or unknown number of Surviving charterS CHRONOLOGICAL SPREAD (by earliest possible decade of creation) 400 Despite losses, the surviving documents point to a gradual increase Copies Originals in their use in the twelh century. 300 200 100 0 109 0s 110 0s 111 0s 112 0s 113 0s 114 0s 115 0s 116 0s 1170s 118 0s 119 0s 120 0s 121 0s 122 0s 123 0s 124 0s TYPES OF DONOR typeS of donor – Example of Melrose Abbey’s Charters It was common for monasteries to seek charters from those in Lay Lords Kings positions of authority in the kingdom: lay lords, kings and bishops. -

Events of the Reformation Part 1 – Church Becomes Powerful Institution

May 20, 2018 Events of the Reformation Protestants and Roman Catholics agree on first 5 centuries. What changed? Why did some in the Church want reform by the 16th century? Outline Why the Reformation? 1. Church becomes powerful institution. 2. Additional teaching and practices were added. 3. People begin questioning the Church. 4. Martin Luther’s protest. Part 1 – Church Becomes Powerful Institution Evidence of Rome’s power grab • In 2nd century we see bishops over regions; people looked to them for guidance. • Around 195AD there was dispute over which day to celebrate Passover (14th Nissan vs. Sunday) • Polycarp said 14th Nissan, but now Victor (Bishop of Rome) liked Sunday. • A council was convened to decide, and they decided on Sunday. • But bishops of Asia continued the Passover on 14th Nissan. • Eusebius wrote what happened next: “Thereupon Victor, who presided over the church at Rome, immediately attempted to cut off from the common unity the parishes of all Asia, with the churches that agreed with them, as heterodox [heretics]; and he wrote letters and declared all the brethren there wholly excommunicate.” (Eus., Hist. eccl. 5.24.9) Everyone started looking to Rome to settle disputes • Rome was always ending up on the winning side in their handling of controversial topics. 1 • So through a combination of the fact that Rome was the most important city in the ancient world and its bishop was always right doctrinally then everyone started looking to Rome. • So Rome took that power and developed it into the Roman Catholic Church by the 600s. Church granted power to rule • Constantine gave the pope power to rule over Italy, Jerusalem, Constantinople and Alexandria. -

VWR Circulators and Chillers

VWR Circulators and Chillers Superior Temperature Control Equipment Clockwise from top left: 13721-200, 13721-172, 13721-138, 13721-082 Controllers Table of Contents. Page Product Features. 2-3 Precise Controllers Controllers . 4-5 Choice of four controllers. From state-of-the-art program- VWR Signature` mable designs that provide Refrigerated/Heating ultimate control, to the analog Circulating Baths. 6-10 design that is perfect for less demanding applications. How To Choose A Chiller . 11 VWR Signature Recirculating Chillers . 12-13 VWR Signature Heating Immersion Circulator. 14 Durable Design VWR` Open Bath Systems . 15 Immersed parts and reservoirs are made of corrosion-fighting VWR Signature stainless steel. The exterior Heating Circulating Baths . 16-17 surface is a tough powder coating for easy clean-up. VWR Refrigerated/Heating Circulating Baths. 18-21 VWR Immersion & Flow-Through Coolers . 22 VWR Ambient Bath Cooler. 22 Double Safety VWR Heating Recirculator . 22 Your equipment and work are protected with redundant over VWR Heating Immersion Circulators . 23 temperature and low liquid cutoff standard on all circula- VWR Heating Circulating Baths . 24-25 tors. 60Hz models are CSA approved, 50Hz models carry Accessories . 26 the CE mark. At-a-Glance Chart . 27 Environmentally Responsible VWR Refrigerated Circulators and Chillers use R-134a refrigerant, and no ozone- depleting CFC’s are used in the manufacturing process. All instruments are manufactured in an ISO 9001 accredited facility. 2 To order, call 1-800-932-5000 or visit vwr.com Controllers Time Savers Advanced refrigeration sys- tems and high wattage heaters respond quickly to temperature changes. You'll have minimum waiting time for your circulator to stabilize. -

Pagan Survivals, Superstitions and Popular Cultures in Early Medieval Pastoral Literature

Bernadette Filotas PAGAN SURVIVALS, SUPERSTITIONS AND POPULAR CULTURES IN EARLY MEDIEVAL PASTORAL LITERATURE Is medieval pastoral literature an accurate reflection of actual beliefs and practices in the early medieval West or simply of literary conventions in- herited by clerical writers? How and to what extent did Christianity and traditional pre-Christian beliefs and practices come into conflict, influence each other, and merge in popular culture? This comprehensive study examines early medieval popular culture as it appears in ecclesiastical and secular law, sermons, penitentials and other pastoral works – a selective, skewed, but still illuminating record of the be- liefs and practices of ordinary Christians. Concentrating on the five cen- turies from c. 500 to c. 1000, Pagan Survivals, Superstitions and Popular Cultures in Early Medieval Pastoral Literature presents the evidence for folk religious beliefs and piety, attitudes to nature and death, festivals, magic, drinking and alimentary customs. As such it provides a precious glimpse of the mu- tual adaptation of Christianity and traditional cultures at an important period of cultural and religious transition. Studies and Texts 151 Pagan Survivals, Superstitions and Popular Cultures in Early Medieval Pastoral Literature by Bernadette Filotas Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Canadian Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, through the Aid to Scholarly Publications Programme, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION Filotas, Bernadette, 1941- Pagan survivals, superstitions and popular cultures in early medieval pastoral literature / by Bernadette Filotas. -

The Catholic Doctrine of Transubstantiation Is Perhaps the Most Well Received Teaching When It Comes to the Application of Greek Philosophy

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses 2010 The aC tholic Doctrine of Transubstantiation: An Exposition and Defense Pat Selwood Bucknell University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Selwood, Pat, "The aC tholic Doctrine of Transubstantiation: An Exposition and Defense" (2010). Honors Theses. 11. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/11 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My deepest appreciation and gratitude goes out to those people who have given their support to the completion of this thesis and my undergraduate degree on the whole. To my close friends, Carolyn, Joseph and Andrew, for their great friendship and encouragement. To my advisor Professor Paul Macdonald, for his direction, and the unyielding passion and spirit that he brings to teaching. To the Heights, for the guidance and inspiration they have brought to my faith: Crescite . And lastly, to my parents, whose love, support, and sacrifice have given me every opportunity to follow my dreams. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction………………………………..………………………………………………1 Preface: Explanation of Terms………………...………………………………………......5 Chapter One: Historical Analysis of the Doctrine…………………………………...……9 -

The Limits of Communication Between Mortals and Immortals in the Homeric Hymns

Body Language: The Limits of Communication between Mortals and Immortals in the Homeric Hymns. Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Bridget Susan Buchholz, M.A. Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Sarah Iles Johnston Fritz Graf Carolina López-Ruiz Copyright by Bridget Susan Buchholz 2009 Abstract This project explores issues of communication as represented in the Homeric Hymns. Drawing on a cognitive model, which provides certain parameters and expectations for the representations of the gods, in particular, for the physical representations their bodies, I examine the anthropomorphic representation of the gods. I show how the narratives of the Homeric Hymns represent communication as based upon false assumptions between the mortals and immortals about the body. I argue that two methods are used to create and maintain the commonality between mortal bodies and immortal bodies; the allocation of skills among many gods and the transference of displays of power to tools used by the gods. However, despite these techniques, the texts represent communication based upon assumptions about the body as unsuccessful. Next, I analyze the instances in which the assumed body of the god is recognized by mortals, within a narrative. This recognition is not based upon physical attributes, but upon the spoken self identification by the god. Finally, I demonstrate how successful communication occurs, within the text, after the god has been recognized. Successful communication is represented as occurring in the presence of ritual references. -

Board of County Commissioners Agenda Thursday, December 14,2017,9:00 Am Commission Chambers, Room B-11 I

BOARD OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS AGENDA THURSDAY, DECEMBER 14,2017,9:00 AM COMMISSION CHAMBERS, ROOM B-11 I. PROCLAMATIONS/PRESENTATIONS 1. Presentation of FY 2017 annual report-Susan Duffy, Topeka Transit. 2. Presentation regarding the Equifest event to be held on February 23, 24, and 25, 2018-Justine Staten, Kansas Horse Council. 3. GraceMed Third Quarter Report-Alice Weingartner. 4. Overview of the Court's proposed evidence presentation system-Chuck Hydovitz, Court Administration. II. UNFINISHED BUSINESS III. CONSENT AGENDA 1. Acknowledge receipt of the December 13th Expocentre Advisory Board Meeting agenda and minutes of the November 8th meeting-Kansas Expocentre. 2. Acknowledge receipt of notice of Ambulance Advisory Board meetings in 2018 (January 24; April 25; July 25; and October 24, all at 4:00p.m. in the Topeka/Shawnee County Public Library }-Emergency Management. 3. Consider authorization and execution of Contract C448-2017 with Imaging Office Systems, Inc. (sole source) for annual maintenance of the PSIGEN optical scanning and indexing software in an amount of$4,725.00 with funding from the 2017 budget-Appraiser. 4. Acknowledge receipt of correspondence from Cox Communications regarding removal ofFM on Channel237 beginning January 1, 2018. IV. NEW BUSINESS A. COUNTY CLERK- Cynthia Beck 1. Consider all voucher payments. 2. Consider correction orders. B. COURT ADMINISTRATION- Chuck Hydovitz 1. Consider authorization and execution of Contract C449-2017 with Stenograph (sole source) for the purchase of four Court Reporter machines at a total cost of $21,180.00 with a trade-in discount of$5,600.00 for a final cost of$15,580.00 with funding from the 2017 budget. -

Introduction to Various Theological Systems Within the Christian Tradition

Introduction to Theological Systems: Dr. Paul R. Shockley Theological Systems Dogmatic Theology: A doctrine or body of doctrines of theology and religion formally stated and authoritatively proclaimed by a group. Calvinist Theology John Calvin (1509-1564) French Institutes – 80 chapter document explaining his views Presbyterian churches Jonathan Edwards, George Whitfield, Charles Spurgeon, Charles Hodge, William Shedd, Benjamin Warfield, Cornelius Van Til Westminster Confession - 1647 Emphases of Calvinism Sovereignty Predestination TULIP – Synod of Dort (1619) Total Depravity Unconditional Election Limited Atonement Irresistible Grace Perseverance of the Saints Arminian Theology Jacob Arminius (1560-1609) Dutch Remonstrance – 1610 document by followers of Arminius explaining his doctrine Methodist, Wesleyan, Episcopalian, Anglican, Free Will Baptist churches John Wesley, H. Orton Wiley Emphases of Arminianism God limits His sovereignty in accordance with man’s freedom – all divine decrees are based on foreknowledge Prevenient Grace – Prevenient grace has removed the guilt and condemnation of Adam’s sin – it reverses the curse Emphases of Arminianism Man is a sinner but not totally depravity (Free Will) Conditional Election based on the foreknowledge of God (God does not predestine all things) Unlimited Atonement Resistible Grace Salvation Insecure Covenant Theology Johann Bullinger (1504-1575) Swiss He was the sole author of Second Helvetic Confession of 1566, which gives a clear statement of the Reformed doctrine. Reformed churches Johannes Wollebius, William Ames, Johannes Cocceius, Hermann Witsius Westminster Confession – 1647 Emphases of Covenantism A system of interpreting the Scriptures on the basis of two covenants: the covenant of works and the covenant of grace. Some add the covenant of redemption. Importance of grace – In every age, believers are always saved by grace. -

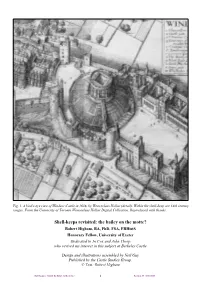

Shell Keeps at Carmarthen Castle and Berkeley Castle

Fig. 1. A bird's-eye view of Windsor Castle in 1658, by Wenceslaus Hollar (detail). Within the shell-keep are 14th century ranges. From the University of Toronto Wenceslaus Hollar Digital Collection. Reproduced with thanks. Shell-keeps revisited: the bailey on the motte? Robert Higham, BA, PhD, FSA, FRHistS Honorary Fellow, University of Exeter Dedicated to Jo Cox and John Thorp, who revived my interest in this subject at Berkeley Castle Design and illustrations assembled by Neil Guy Published by the Castle Studies Group. © Text: Robert Higham Shell-keeps re-visited: the bailey on the motte? 1 Revision 19 - 05/11/2015 Fig. 2. Lincoln Castle, Lucy Tower, following recent refurbishment. Image: Neil Guy. Abstract Scholarly attention was first paid to the sorts of castle ● that multi-lobed towers built on motte-tops discussed here in the later 18th century. The “shell- should be seen as a separate form; that truly keep” as a particular category has been accepted in circular forms (not on mottes) should be seen as a academic discussion since its promotion as a medieval separate form; design by G.T. Clark in the later 19th century. Major ● that the term “shell-keep” should be reserved for works on castles by Ella Armitage and A. Hamilton mottes with structures built against or integrated Thompson (both in 1912) made interesting observa- with their surrounding wall so as to leave an open, tions on shell-keeps. St John Hope published Windsor central space with inward-looking accommodation; Castle, which has a major example of the type, a year later (1913).