Pergamon Altar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sons and Fathers in the Catalogue of Argonauts in Apollonius Argonautica 1.23-233

Sons and fathers in the catalogue of Argonauts in Apollonius Argonautica 1.23-233 ANNETTE HARDER University of Groningen [email protected] 1. Generations of heroes The Argonautica of Apollonius Rhodius brings emphatically to the attention of its readers the distinction between the generation of the Argonauts and the heroes of the Trojan War in the next genera- tion. Apollonius initially highlights this emphasis in the episode of the Argonauts’ departure, when the baby Achilles is watching them, at AR 1.557-5581 σὺν καί οἱ (sc. Chiron) παράκοιτις ἐπωλένιον φορέουσα | Πηλείδην Ἀχιλῆα, φίλωι δειδίσκετο πατρί (“and with him his wife, hold- ing Peleus’ son Achilles in her arms, showed him to his dear father”)2; he does so again in 4.866-879, which describes Thetis and Achilles as a baby. Accordingly, several scholars have focused on the ways in which 1 — On this marker of the generations see also Klooster 2014, 527. 2 — All translations of Apollonius are by Race 2008. EuGeStA - n°9 - 2019 2 ANNETTE HARDER Apollonius has avoided anachronisms by carefully distinguishing between the Argonauts and the heroes of the Trojan War3. More specifically Jacqueline Klooster (2014, 521-530), in discussing the treatment of time in the Argonautica, distinguishes four periods of time to which Apollonius refers: first, the time before the Argo sailed, from the beginning of the cosmos (featured in the song of Orpheus in AR 1.496-511); second, the time of its sailing (i.e. the time of the epic’s setting); third, the past after the Argo sailed and fourth the present inhab- ited by the narrator (both hinted at by numerous allusions and aitia). -

The Medici Aphrodite Angel D

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2005 A Hellenistic masterpiece: the Medici Aphrodite Angel D. Arvello Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Arvello, Angel D., "A Hellenistic masterpiece: the Medici Aphrodite" (2005). LSU Master's Theses. 2015. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2015 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A HELLENISTIC MASTERPIECE: THE MEDICI APRHODITE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The School of Art by Angel D. Arvello B. A., Southeastern Louisiana University, 1996 May 2005 In Memory of Marcel “Butch” Romagosa, Jr. (10 December 1948 - 31 August 1998) ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to acknowledge the support of my parents, Paul and Daisy Arvello, the love and support of my husband, Kevin Hunter, and the guidance and inspiration of Professor Patricia Lawrence in addition to access to numerous photographs of hers and her coin collection. I would also like to thank Doug Smith both for his extensive website which was invaluable in writing chapter four and for his permission to reproduce the coin in his private collection. -

SEAT of the WORLD of Beautiful and Gentle Tales Are Discovered and Followed Through Their Development

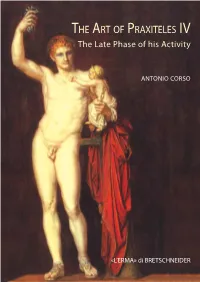

The book is focused on the late production of the 4th c. BC Athenian sculptor Praxiteles and in particular 190 on his oeuvre from around 355 to around 340 BC. HE RT OF RAXITELES The most important works of this master considered in this essay are his sculptures for the Mausoleum of T A P IV Halicarnassus, the Apollo Sauroctonus, the Eros of Parium, the Artemis Brauronia, Peitho and Paregoros, his Aphrodite from Corinth, the group of Apollo and Poseidon, the Apollinean triad of Mantinea, the The Late Phase of his Activity Dionysus of Elis, the Hermes of Olympia and the Aphrodite Pseliumene. Complete lists of ancient copies and variations derived from the masterpieces studied here are also provided. The creation by the artist of an art of pleasure and his visual definition of a remote and mythical Arcadia SEAT OF THE WORLD of beautiful and gentle tales are discovered and followed through their development. ANTONIO CORSO Antonio Corso attended his curriculum of studies in classics and archaeology in Padua, Athens, Frank- The Palatine of Ancient Rome furt and London. He published more than 100 scientific essays (articles and books) in well refereed peri- ate Phase of his Activity Phase ate odicals and series of books. The most important areas covered by his studies are the ancient art criticism L and the knowledge of classical Greek artists. In particular he collected in three books all the written tes- The The timonia on Praxiteles and in other three books he reconstructed the career of this sculptor from around 375 to around 355 BC. -

Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements Art

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements Art 7-1-2000 Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures] J.L. Benson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgs Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Benson, J.L., "Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements [full text, not including figures]" (2000). Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements. 1. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/art_jbgs/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Greek Sculpture and the Four Elements by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cover design by Jeff Belizaire About this book This is one part of the first comprehensive study of the development of Greek sculpture and painting with the aim of enriching the usual stylistic-sociological approaches through a serious, disciplined consideration of the basic Greek scientific orientation to the world. This world view, known as the Four Elements Theory, came to specific formulation at the same time as the perfected contrapposto of Polykleitos and a concern with the four root colors in painting (Polygnotos). All these factors are found to be intimately intertwined, for, at this stage of human culture, the spheres of science and art were not so drastically differentiated as in our era. The world of the four elements involved the concepts of polarity and complementarism at every level. -

ΤΑΡΤΑΡΟΣ in Greco-Roman Culture, Second Temple Judaism, and Philo of Alexandria* Clint Burnett (Boston College)

Going Through Hell; ΤΑΡΤΑΡΟΣ in Greco-Roman Culture, Second Temple Judaism, and Philo of Alexandria* Clint Burnett (Boston College) Tis article questions the longstanding supposition that the eschatology of the Second Temple period was solely infuenced by Persian or Iranian eschatology, arguing instead that the litera- ture of this period refects awareness of several key Greco-Roman mythological concepts. In particular, the concepts of Tartarus and the Greek myths of Titans and Giants underlie much of the treatment of eschatology in the Jewish literature of the period. A thorough treatment of Tartarus and related concepts in literary and non-literary sources from ancient Greek and Greco-Roman culture provides a backdrop for a discussion of these themes in the Second Tem- ple period and especially in the writings of Philo of Alexandria. I. Introduction Contemporary scholarship routinely explores connections between Greco- Roman culture and Second Temple Judaism, but one aspect of this investiga- tion that has not received the attention it deserves is eschatology. Te view that the eschatology of the Second Temple period was shaped largely by Persian es- chatology remains dominant in the feld.1 As James Barr has observed, “Many of the scholars of the ‘biblical theology’ period, were very anxious to make it clear that biblical thought was entirely distinct from, and owed nothing to, Greek thought. … Iranian infuence, however, seemed … less of a threat.”2 Tis is somewhat surprising, given that many Second Temple Jewish texts, including the writings of Philo of Alexandria, mention eschatological con- cepts developed in a Greco-Roman context. Signifcant among these are the many references to the Greco-Roman subterranean prison of Tartarus and the related mythology of the Titans and Giants. -

CAST GALLERY Section Contents 1. History of the Collection 2. Cast

CAST GALLERY Section Contents 1. History of the Collection 2. Cast Collection listed by historical period 3. A History of Greek Sculpture Based on the Cast Collection a. Archaic Period, Introduction b. Fifth Century BCE, Introduction c. Second Half of Fifth Century BCE, Introduction d. Fifth Century, 425-400 BCE e. Fourth Century BCE, Introduction 4. Hellenistic Period, Introduction 5. Greek Architectural Orders 6. Cast Collection listed by location in Pickard Hall 7. Cast Gallery Expanded Labels MAA 6/2012 Docent Manual Volume 1 Cast Gallery 1 CAST GALLERY History of the Collection The University of Missouri-Columbia owns about one hundred plaster casts of sculpture, mainly Greek or Roman, but eleven represent later periods. In addition, scale models of parts of three buildings are examples of the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian orders. Four of the casts were the gift of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in 1973, but the bulk of the collection was personally selected for the University in 1895 and 1902 by John Pickard (1858- 1937), Professor of Classical Archaeology and founder, in 1892, of the Department of Art History and Archaeology at the University of Missouri. The records of the 1895 purchase show that the first fifty casts and the architectural models were acquired from casting studios in Germany, France, and England. Apparently no correspondence exists concerning the second acquisition in 1902, but the local newspaper reported that thirty or forty casts were acquired. Until 1940 the collection was displayed in a large gallery on the third floor of Academic Hall, the campus administration building, now called Jesse Hall, but, for a twenty-year period from 1940 to 1960, the casts were hidden from view, pushed aside to provide space for art classes. -

The 'Trial by Water' in Greek Myth and Literature

Leeds International Classical Studies 7.1 (2008) ISSN 1477-3643 (http://www.leeds.ac.uk/classics/lics/) © Fiona McHardy The ‘trial by water’ in Greek myth and literature FIONA MCHARDY (ROEHAMPTON UNIVERSITY) ABSTRACT: This paper discusses the theme of casting ‘unchaste’ women into the sea as a punishment in Greek myth and literature. Particular focus will be given to the stories of Danaë, Augë, Aerope and Phronime, who are all depicted suffering this punishment at the hands of their fathers. While Seaford (1990) has emphasized the theme of imprisonment which occurs in some of the stories involving the ‘floating chest’, I turn my attention instead to the theme of the sea. The coincidence in these stories of the threat of drowning for apparent promiscuity or sexual impurity with the escape of those girls who are innocent can be explained by the phenomenon of the ‘trial by water’ as evidenced in Babylonian and other early law codes (cf. Glotz 1904). Further evidence for this theory can be found in ancient novels where the trial of the heroine for sexual purity is often a key theme. The significance of chastity in the myths and in Athenian society is central to understanding the story patterns. The interrelationship of mythic and social ideals is drawn out in the paper. This paper examines the punishment of ‘unchaste’ women in Greek myth and literature, in particular their representation in Euripides’ fragmentary Augë, Cretan Women and Danaë. My focus is on punishments involving the sea, where it is possible to discern two interrelated strands in the tales.1 The first strand involves an angry parent condemning an errant daughter to be cast into the sea with the intention of drowning her. -

THE APOXYOMENOS of LYSIPPUS. in the Hellenic Journal for 1903

THE APOXYOMENOS OF LYSIPPUS. IN the Hellenic Journal for 1903, while publishing some heads of Apollo, I took occasion to express my doubts as to the expediency of hereafter taking the Apoxyomenos as the norm of the works of Lysippus. These views, how- ever, were not expressed in any detail, and occurring at the end of a paper devoted to other matters, have not attracted much attention from archaeolo- gists. The subject is of great importance, since if my contention be justified, much of the history of Greek sculpture in the fourth century will have to be reconsidered. Being still convinced of the justice of the view which I took two years ago, I feel bound to bring it forward in more detail and with a fuller statement of reasons. Our knowledge of many of the sculptors of the fourth century, Praxiteles, Scopas, Bryaxis, Timotheus, and others, has been enormously enlarged during the last thirty years through our discovery of works proved by documentary evidence to have been either actually executed by them, or at least made under their direction. But in the case of Lysippus no such discovery was made until the very important identification of the Agias at Delphi as a copy of a statue by this master. Hitherto we had been content to take the Apoxyomenos as the best indication of Lysippic style ; and apparently few archaeologists realized how slender was the evidence on which its assignment to Lysippus was based. That assignment took place many years ago, when archaeological method was lax ; and it has not been subjected to sufficiently searching criticism. -

The Voyage of the Argo and Other Modes of Travel in Apollonius’ Argonautica

THE VOYAGE OF THE ARGO AND OTHER MODES OF TRAVEL IN APOLLONIUS’ ARGONAUTICA Brian D. McPhee A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Classics. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: William H. Race James J. O’Hara Emily Baragwanath © 2016 Brian D. McPhee ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Brian D. McPhee: The Voyage of the Argo and Other Modes of Travel in Apollonius’ Argonautica (Under the direction of William H. Race) This thesis analyzes the Argo as a vehicle for travel in Apollonius’ Argonautica: its relative strengths and weaknesses and ultimately its function as the poem’s central mythic paradigm. To establish the context for this assessment, the first section surveys other forms of travel in the poem, arranged in a hierarchy of travel proficiency ranging from divine to heroic to ordinary human mobility. The second section then examines the capabilities of the Argo and its crew in depth, concluding that the ship is situated on the edge between heroic and human travel. The third section confirms this finding by considering passages that implicitly compare the Argo with other modes of travel through juxtaposition. The conclusion follows cues from the narrator in proposing to read the Argo as a mythic paradigm for specifically human travel that functions as a metaphor for a universal and timeless human condition. iii parentibus meis “Finis origine pendet.” iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I owe a tremendous debt of gratitude to my director and mentor, William Race. -

AP Art History Greek Study Guide

AP Art History Greek Study Guide "I cannot teach anybody anything. I can only make them think." - Socrates (470-399 BCE) CH. 5 (p. 101 – 155) Textbook Timeline Geometric Archaic Early Classical High Classical Late Classical Hellenistic 900-700 600 BCE- 480 Severe 450 BCE-400 BCE 400-323 BCE 323 BCE-31 BCE BCE 480 BCE- 450 BCE BCE Artists: Phidias, Artists: Praxiteles, Artists: Pythokritos, Artists: ??? Polykleitos, Myron Scopas, Orientalizing Lysippus Polydorus, Artists: Kritios 700-600 Agesander, Artworks: Artworks: BCE Artworks: Athenodorus kouroi and Artworks: Riace warrior, Aphrodite of Knidos, korai Pedimental Zeus/Poseidon, Hermes & the Infant Artworks: sculpture of the Doryphoros, Dionysus, Dying Gaul, Temple of Diskobolos, Nike Apoxyomenos, Nike of Samothrace, Descriptions: Aphaia and the Adjusting her Farnes Herakles Barberini Faun, Idealization, Temple of Sandal Seated Boxer, Old Market Woman, Artemis, Descriptions: stylized, Laocoon & his Sons FRONTAL, Kritios boy Descriptions: NATURAL, humanized, rigid Idealization, relaxed, Descriptions: unemotional, elongation EMOTIONAL, Descriptions: PERFECTION, dramatic, Contrapposto, self-contained exaggeration, movement movement, individualistic Vocabulary 1. Acropolis 14. Frieze 27. Pediment 2. Agora 15. Gigantomachy 28. Peplos 3. Amphiprostyle 16. Isocephalism 29. Peristyle 4. Amphora 17. In Situ 30. Portico 5. Architrave 18. Ionic 31. Propylaeum 6. Athena 19. Kiln 32. Relief Sculpture 7. Canon 20. Kouros / Kore 33. Shaft 8. Caryatid / Atlantid 21. Krater 34. Stele 9. Contrapposto 22. Metope 35. Stoa 10. Corinthian 23. Mosaic 36. Tholos 11. Cornice 24. Nike 37. Triglyph 12. Doric 25. Niobe 38. Zeus 13. Entablature 26. Panatheonic Way To-do List: ● Know the key ideas, vocabulary, & dates ● Complete the notes pages / Study Guides / any flashcards you may want to add to your ongoing stack ● Visit Khan Academy Image Set Key Ideas *Athenian Agora ● Greeks are interested in the human figure the idea of Geometric perfection. -

Mythology Study Questions

Greek Mythology version 1.0 Notes: These are study questions on Apollodorus’ Library of Greek Mythology. They are best used during or after reading the Library, though many of them can be used independently. In some cases Apollodorus departs from other NJCL sources, and those other sources are more authoritative/likely to come up on tests and in Certamen. In particular, it is wise to read the epics (Iliad, Odyssey, Aeneid, Metamorphoses) for the canonical versions of several stories. Most of these are in question form, and suitable for use as certamen questions, but many of the later questions are in the format of NJCL test questions instead. Students should not be worried by the number of questions here, or the esoteric nature of some of them. Mastering every one of these questions is unnecessary except, perhaps, for those aiming to get a top score on the NJCL Mythology Exam, compete at the highest levels of Certamen, and the like. Further, many of the questions here are part of longer stories; learning a story will often help a student answer several of the questions at once. Apollodorus does an excellent job of presenting stories succinctly and clearly. The best translation of the Library currently available is probably the Oxford Word Classics edition by Robin Hard. That edition is also excellent for its notes, which include crucial information that Apollodorus omits as well as comparisons with other versions of the stories. I am grateful for any corrections, comments, or suggestions. You can contact me at [email protected]. New versions of this list will be posted occasionally. -

Euripides and Gender: the Difference the Fragments Make

Euripides and Gender: The Difference the Fragments Make Melissa Karen Anne Funke A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee: Ruby Blondell, Chair Deborah Kamen Olga Levaniouk Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Classics © Copyright 2013 Melissa Karen Anne Funke University of Washington Abstract Euripides and Gender: The Difference the Fragments Make Melissa Karen Anne Funke Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Ruby Blondell Department of Classics Research on gender in Greek tragedy has traditionally focused on the extant plays, with only sporadic recourse to discussion of the many fragmentary plays for which we have evidence. This project aims to perform an extensive study of the sixty-two fragmentary plays of Euripides in order to provide a picture of his presentation of gender that is as full as possible. Beginning with an overview of the history of the collection and transmission of the fragments and an introduction to the study of gender in tragedy and Euripides’ extant plays, this project takes up the contexts in which the fragments are found and the supplementary information on plot and character (known as testimonia) as a guide in its analysis of the fragments themselves. These contexts include the fifth- century CE anthology of Stobaeus, who preserved over one third of Euripides’ fragments, and other late antique sources such as Clement’s Miscellanies, Plutarch’s Moralia, and Athenaeus’ Deipnosophistae. The sections on testimonia investigate sources ranging from the mythographers Hyginus and Apollodorus to Apulian pottery to a group of papyrus hypotheses known as the “Tales from Euripides”, with a special focus on plot-type, especially the rape-and-recognition and Potiphar’s wife storylines.