Cephalopod Locomotion Lab Elementary School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

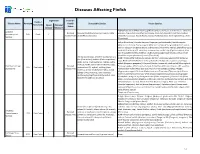

Diseases Affecting Finfish

Diseases Affecting Finfish Legislation Ireland's Exotic / Disease Name Acronym Health Susceptible Species Vector Species Non-Exotic Listed National Status Disease Measures Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), goldfish (Carassius auratus), crucian carp (C. carassius), Epizootic Declared Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), redfin common carp and koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), silver carp (Hypophtalmichthys molitrix), Haematopoietic EHN Exotic * Disease-Free perch (Percha fluviatilis) Chub (Leuciscus spp), Roach (Rutilus rutilus), Rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), tench Necrosis (Tinca tinca) Beluga (Huso huso), Danube sturgeon (Acipenser gueldenstaedtii), Sterlet sturgeon (Acipenser ruthenus), Starry sturgeon (Acipenser stellatus), Sturgeon (Acipenser sturio), Siberian Sturgeon (Acipenser Baerii), Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), goldfish (Carassius auratus), Crucian carp (C. carassius), common carp and koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), silver carp (Hypophtalmichthys molitrix), Chub (Leuciscus spp), Roach (Rutilus rutilus), Rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), tench (Tinca tinca) Herring (Cupea spp.), whitefish (Coregonus sp.), North African catfish (Clarias gariepinus), Northern pike (Esox lucius) Catfish (Ictalurus pike (Esox Lucius), haddock (Gadus aeglefinus), spp.), Black bullhead (Ameiurus melas), Channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus), Pangas Pacific cod (G. macrocephalus), Atlantic cod (G. catfish (Pangasius pangasius), Pike perch (Sander lucioperca), Wels catfish (Silurus glanis) morhua), Pacific salmon (Onchorhynchus spp.), Viral -

Nautiloid Shell Morphology

MEMOIR 13 Nautiloid Shell Morphology By ROUSSEAU H. FLOWER STATEBUREAUOFMINESANDMINERALRESOURCES NEWMEXICOINSTITUTEOFMININGANDTECHNOLOGY CAMPUSSTATION SOCORRO, NEWMEXICO MEMOIR 13 Nautiloid Shell Morphology By ROUSSEAU H. FLOIVER 1964 STATEBUREAUOFMINESANDMINERALRESOURCES NEWMEXICOINSTITUTEOFMININGANDTECHNOLOGY CAMPUSSTATION SOCORRO, NEWMEXICO NEW MEXICO INSTITUTE OF MINING & TECHNOLOGY E. J. Workman, President STATE BUREAU OF MINES AND MINERAL RESOURCES Alvin J. Thompson, Director THE REGENTS MEMBERS EXOFFICIO THEHONORABLEJACKM.CAMPBELL ................................ Governor of New Mexico LEONARDDELAY() ................................................... Superintendent of Public Instruction APPOINTEDMEMBERS WILLIAM G. ABBOTT ................................ ................................ ............................... Hobbs EUGENE L. COULSON, M.D ................................................................. Socorro THOMASM.CRAMER ................................ ................................ ................... Carlsbad EVA M. LARRAZOLO (Mrs. Paul F.) ................................................. Albuquerque RICHARDM.ZIMMERLY ................................ ................................ ....... Socorro Published February 1 o, 1964 For Sale by the New Mexico Bureau of Mines & Mineral Resources Campus Station, Socorro, N. Mex.—Price $2.50 Contents Page ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION -

Shells Shells Are the Remains of a Group of Animals Called Molluscs

Inspire - Educate – Showcase Shells Shells are the remains of a group of animals called molluscs. Bivalves Molluscs are soft-bodied animals inhabiting marine, land and Bivalves are molluscs made up of two shells joined by a hinge with freshwater habitats. The shells we commonly come across on the interlocking teeth. The shells are usually held together by a tough beach belong to one of two groups of molluscs, either gastropods ligament. These creatures also have a set of two tubes which which have one shell, or bivalves which have two shells. The material sometimes stick out from shell allowing the animal to breathe and making up the shell is secreted by special glands of the animal living feed. within it. Some commonly known bivalves include clams, cockles, mussels, scallops and oysters. Can you think of any others? Oysters and mussels attach themselves to solid objects such as jetty pylons or rocks on the sea floor and filter feed by taking Gastropod = One Shell Bivalve = Two Shells water into one tube and removing the tiny particles of plankton from the water. In contrast, scallops and cockles are moving Particular shell shapes have been adapted to suit the habitat and bivalves and can either swim through the conditions in which the animals live, helping them to survive. The water or pull themselves through the sand wedge shape of a cockle shell allows them to easily burrow into the with their muscular, soft bodies. sand. Ribs, folds and frills on many molluscs help to strengthen the shell and provide extra protection from predators. -

Freshwater Mussels "Do You Mean Muscles?" Actually, We're Talking About Little Animals That Live in the St

Our Mighty River Keepers Freshwater Mussels "Do you mean muscles?" Actually, we're talking about little animals that live in the St. Lawrence River called "freshwater mussels." "Oh, like zebra mussels?" Exactly! Zebra mussels are a non-native and invasive type of freshwater mussel that you may have already heard about. Zebra mussels are from faraway lakes and rivers in Europe and Asia; they travelled here in the ballast of cargo ships. When non-native: not those ships came into the St. Lawrence River, they dumped the originally belonging in a zebra mussels into the water without realizing it. Since then, particular place the zebra mussels have essentially taken over the river. invasive: tending to The freshwater mussels which are indigenous, or native, to the spread harmfully St. Lawrence River, are struggling to keep up with the growing number of invasive zebra mussels. But we'll talk more about ballast: heavy material that, later. (like stones, lead, or even water) placed in the bottom of a ship to For now, let's take a closer look at what it improve its stability means to be a freshwater mussel... indigenous: originally belonging in a particular place How big is a zebra mussel? 1 "What is a mussel?" Let's classify it to find out! We use taxonomy (the study of naming and classifying groups of organisms based on their characteristics) as a way to organize all the organisms of our world inside our minds. Grouping mussels with organisms that are similar can help us answer the question "What KKingdom:ingdom: AAnimalianimalia is a mussel?" Start at the top of our flow chart with the big group called the Kingdom: Animalia (the Latin way to say "animals"). -

Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus Dofleini) Care Manual

Giant Pacific Octopus Insert Photo within this space (Enteroctopus dofleini) Care Manual CREATED BY AZA Aquatic Invertebrate Taxonomic Advisory Group IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA Animal Welfare Committee Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) Care Manual Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Aquatic Invertebrate Taxon Advisory Group (AITAG) (2014). Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) Care Manual. Association of Zoos and Aquariums, Silver Spring, MD. Original Completion Date: September 2014 Dedication: This work is dedicated to the memory of Roland C. Anderson, who passed away suddenly before its completion. No one person is more responsible for advancing and elevating the state of husbandry of this species, and we hope his lifelong body of work will inspire the next generation of aquarists towards the same ideals. Authors and Significant Contributors: Barrett L. Christie, The Dallas Zoo and Children’s Aquarium at Fair Park, AITAG Steering Committee Alan Peters, Smithsonian Institution, National Zoological Park, AITAG Steering Committee Gregory J. Barord, City University of New York, AITAG Advisor Mark J. Rehling, Cleveland Metroparks Zoo Roland C. Anderson, PhD Reviewers: Mike Brittsan, Columbus Zoo and Aquarium Paula Carlson, Dallas World Aquarium Marie Collins, Sea Life Aquarium Carlsbad David DeNardo, New York Aquarium Joshua Frey Sr., Downtown Aquarium Houston Jay Hemdal, Toledo -

Hydraulics Manual Glossary G - 3

Glossary G - 1 GLOSSARY OF HIGHWAY-RELATED DRAINAGE TERMS (Reprinted from the 1999 edition of the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials Model Drainage Manual) G.1 Introduction This Glossary is divided into three parts: · Introduction, · Glossary, and · References. It is not intended that all the terms in this Glossary be rigorously accurate or complete. Realistically, this is impossible. Depending on the circumstance, a particular term may have several meanings; this can never change. The primary purpose of this Glossary is to define the terms found in the Highway Drainage Guidelines and Model Drainage Manual in a manner that makes them easier to interpret and understand. A lesser purpose is to provide a compendium of terms that will be useful for both the novice as well as the more experienced hydraulics engineer. This Glossary may also help those who are unfamiliar with highway drainage design to become more understanding and appreciative of this complex science as well as facilitate communication between the highway hydraulics engineer and others. Where readily available, the source of a definition has been referenced. For clarity or format purposes, cited definitions may have some additional verbiage contained in double brackets [ ]. Conversely, three “dots” (...) are used to indicate where some parts of a cited definition were eliminated. Also, as might be expected, different sources were found to use different hyphenation and terminology practices for the same words. Insignificant changes in this regard were made to some cited references and elsewhere to gain uniformity for the terms contained in this Glossary: as an example, “groundwater” vice “ground-water” or “ground water,” and “cross section area” vice “cross-sectional area.” Cited definitions were taken primarily from two sources: W.B. -

Eight Arms, with Attitude

The link information below provides a persistent link to the article you've requested. Persistent link to this record: Following the link below will bring you to the start of the article or citation. Cut and Paste: To place article links in an external web document, simply copy and paste the HTML below, starting with "<a href" To continue, in Internet Explorer, select FILE then SAVE AS from your browser's toolbar above. Be sure to save as a plain text file (.txt) or a 'Web Page, HTML only' file (.html). In Netscape, select FILE then SAVE AS from your browser's toolbar above. Record: 1 Title: Eight Arms, With Attitude. Authors: Mather, Jennifer A. Source: Natural History; Feb2007, Vol. 116 Issue 1, p30-36, 7p, 5 Color Photographs Document Type: Article Subject Terms: *OCTOPUSES *ANIMAL behavior *ANIMAL intelligence *PLAY *PROBLEM solving *PERSONALITY *CONSCIOUSNESS in animals Abstract: The article offers information on the behavior of octopuses. The intelligence of octopuses has long been noted, and to some extent studied. But in recent years, play, and problem-solving skills has both added to and elaborated the list of their remarkable attributes. Personality is hard to define, but one can begin to describe it as a unique pattern of individual behavior that remains consistent over time and in a variety of circumstances. It will be hard to say for sure whether octopuses possess consciousness in some simple form. Full Text Word Count: 3643 ISSN: 00280712 Accession Number: 23711589 Persistent link to this http://0-search.ebscohost.com.library.bennington.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=23711589&site=ehost-live -

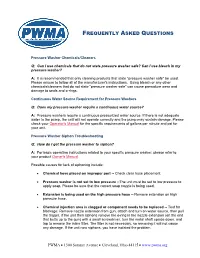

Frequently Asked Questions

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS Pressure Washer Chemicals/Cleaners Q: Can I use chemicals that do not state pressure washer safe? Can I use bleach in my pressure washer? A: It is recommended that only cleaning products that state "pressure washer safe" be used. Please ensure to follow all of the manufacturer's instructions. Using bleach or any other chemicals/cleaners that do not state "pressure washer safe" can cause premature wear and damage to seals and o-rings. Continuous Water Source Requirement for Pressure Washers Q: Does my pressure washer require a continuous water source? A: Pressure washers require a continuous pressurized water source. If there is not adequate water to the pump, the unit will not operate correctly and the pump may sustain damage. Please check your Operator's Manual for the specific requirements of gallons per minute and psi for your unit. Pressure Washer Siphon Troubleshooting Q: How do I get the pressure washer to siphon? A: For basic operating instructions related to your specific pressure washer, please refer to your product Owner's Manual. Possible causes for lack of siphoning include: • Chemical hose placed on improper port -- Check clear hose placement. • Pressure washer is not set to low pressure --The unit must be set to low pressure to apply soap. Please be sure that the correct soap nozzle is being used. • Extension is being used on the high pressure hose -- Remove extension on high pressure hose. • Chemical injection area is clogged or component needs to be replaced -- Test for blockage: Remove nozzle extension from gun, attach and turn on water source, then pull the trigger. -

Intercapsular Embryonic Development of the Big Fin Squid Sepioteuthis Lessoniana (Loliginidae)

Indian Journal of Marine Sciences Vol. 31(2), June 2002, pp. 150-152 Short Communication Intercapsular embryonic development of the big fin squid Sepioteuthis lessoniana (Loliginidae) V. Deepak Samuel & Jamila Patterson* Suganthi Devadason Marine Research Institute, 44, Beach Road, Tuticorin – 628 001, Tamil Nadu, India ( E.mail : [email protected] ) Received 18 June 2001, revised 22 January 2002 The egg masses of big fin squid, Sepioteuthis lessoniana were collected from the wild and their intercapsular embryonic development was studied. The average incubation period of the egg varied between 18-20 days. The cleavage started on the first day and the mantle developed between third and fifth day. The yolk started decreasing eighth day onwards. The tentacles with the sucker primordia on the tip were prominent from tenth day. The yolk totally reduced between thirteenth and seventeenth day and the paralarvae hatched out on eighteenth day.The developmental stages of the embryo inside the capsules during the incubation period is understood. [ Key words: Sepioteuthis lessoniana , intercapsular development ] There are about 660 species of cephalopods in the the death of the embryo. Egg capsules were taken world oceans, of which less than hundred species are everyday to study the developmental stages of the of commercial importance. In the Indian seas, about growing embryos. Size of the egg capsules, eggs and 80 species of cephalopods exist but the main fishery is the embryos inside the eggs were recorded everyday contributed by only a dozen or so. Though they play till hatching. Various stages of development were ob- an important role in the economy of our country, their served and recorded as line drawings and photographs early life cycle and reproductive biology are not yet with the help of a light microscope. -

PLUMBING DICTIONARY Sixth Edition

as to produce smooth threads. 2. An oil or oily preparation used as a cutting fluid espe cially a water-soluble oil (such as a mineral oil containing- a fatty oil) Cut Grooving (cut groov-ing) the process of machining away material, providing a groove into a pipe to allow for a mechani cal coupling to be installed.This process was invented by Victau - lic Corp. in 1925. Cut Grooving is designed for stanard weight- ceives or heavier wall thickness pipe. tetrafluoroethylene (tet-ra-- theseveral lower variouslyterminal, whichshaped re or decalescensecryolite (de-ca-les-cen- ming and flood consisting(cry-o-lite) of sodium-alumi earthfluo-ro-eth-yl-ene) by alternately dam a colorless, thegrooved vapors tools. from 4. anonpressure tool used by se) a decrease in temperaturea mineral nonflammable gas used in mak- metalworkers to shape material thatnum occurs fluoride. while Usedheating for soldermet- ing a stream. See STANK. or the pressure sterilizers, and - spannering heat resistantwrench and(span-ner acid re - conductsto a desired the form vapors. 5. a tooldirectly used al ingthrough copper a rangeand inalloys which when a mixed with phosphoric acid.- wrench)sistant plastics 1. one ofsuch various as teflon. tools to setthe theouter teeth air. of Sometimesaatmosphere circular or exhaust vent. See change in a structure occurs. Also used for soldering alumi forAbbr. tightening, T.F.E. or loosening,chiefly Brit.: orcalled band vapor, saw. steam,6. a tool used to degree of hazard (de-gree stench trap (stench trap) num bronze when mixed with nutsthermal and bolts.expansion 2. (water) straightenLOCAL VENT. -

Defensive Behaviors of Deep-Sea Squids: Ink Release, Body Patterning, and Arm Autotomy

Defensive Behaviors of Deep-sea Squids: Ink Release, Body Patterning, and Arm Autotomy by Stephanie Lynn Bush A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Integrative Biology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Roy L. Caldwell, Chair Professor David R. Lindberg Professor George K. Roderick Dr. Bruce H. Robison Fall, 2009 Defensive Behaviors of Deep-sea Squids: Ink Release, Body Patterning, and Arm Autotomy © 2009 by Stephanie Lynn Bush ABSTRACT Defensive Behaviors of Deep-sea Squids: Ink Release, Body Patterning, and Arm Autotomy by Stephanie Lynn Bush Doctor of Philosophy in Integrative Biology University of California, Berkeley Professor Roy L. Caldwell, Chair The deep sea is the largest habitat on Earth and holds the majority of its’ animal biomass. Due to the limitations of observing, capturing and studying these diverse and numerous organisms, little is known about them. The majority of deep-sea species are known only from net-caught specimens, therefore behavioral ecology and functional morphology were assumed. The advent of human operated vehicles (HOVs) and remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) have allowed scientists to make one-of-a-kind observations and test hypotheses about deep-sea organismal biology. Cephalopods are large, soft-bodied molluscs whose defenses center on crypsis. Individuals can rapidly change coloration (for background matching, mimicry, and disruptive coloration), skin texture, body postures, locomotion, and release ink to avoid recognition as prey or escape when camouflage fails. Squids, octopuses, and cuttlefishes rely on these visual defenses in shallow-water environments, but deep-sea cephalopods were thought to perform only a limited number of these behaviors because of their extremely low light surroundings. -

The Atlantic Coast Surf Clam Fishery, 1965-1974

The Atlantic Coast Surf Clam Fishery, 1965-1974 JOHN W. ROPES Introduction United States twofold from 0.268 made several innovative technological pounds in 1947 to 0.589 pounds in advances in equipment for catching An intense, active fishery for the At 1974 (NMFS, 1975). Much of this con and processing the meats which signifi lantic surf clam, Spisula solidissima, swnption was in the New England cantly increased production. developed from one that historically region (Miller and Nash, 1971). The industry steadily grew during employed unsophisticated harvesting The fishery is centered in the ocean the 1950's with an increase in demand and marketing methods and had a low off the Middle Atlantic coastal states, for its products, but by the early annual production of less than 2 since surf clams are widely distributed 1960's industry representatives suspect million pounds of meats (Yancey and in beds on the continental shelf of the ed that the known resource supply was Welch, 1968). Only 3.2 percent of the Middle Atlantic Bight (Merrill and being depleted and requested research clam meats landed by weight in the Ropes, 1969; Ropes, 1979). Most of assistance (House of Representatives, United States during the half-decade the vessels in the fishery are located 1963). As part of a Federal research 1939-44 were from this resource, but from the State of New York through program begun in 1963 (Merrill and by 1970-74 it amounted to 71.8 per Virginia. The modem-day industry Webster, 1964), vessel captains in the cent. Landings from this fishery during surf clam fleet were interviewed to the three-decade period 1945-74 in gather data on fishing location, effort, John W.