Italian and Russian Verse: Two Cultures and Two Mentalities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rhyme in European Verse: a Case for Quantitative Historical Poetics

1 Rhyme in European Verse: A Case for Quantitative Historical Poetics Boris Maslov & Tatiana Nikitina Keywords rhyme, statistical methods, meter, Historical Poetics, Russian verse The past decade has witnessed an unprecedented rise of interest in objectivist, data-driven approaches to literary history, often grouped together under the heading of digital humanities. The rapid multiplication of software designed to map and chart literature, often on a massive scale, has engendered an anxious (and often unpublicized) reaction. A concern for the future of literary studies, traditionally committed to the study of individual texts accessed through “close reading” of individual passages, is exacerbated in the wake of the emergence of a version of “world literature” that normalizes the study of literary works in translation, effectively jettisoning the philological techniques of explication du texte. This article seeks to bypass these antagonisms by proposing an alternative approach to literary history which, while being rooted in data analysis and employing quantitative methods some of which have been part of a century-old scholarly tradition, retains a twofold focus on the workings of poetic form and on the interaction between national literary traditions—the two topics that have dominated theoretical poetics and comparative literature ever since the inception of these disciplines in the late nineteenth-early twentieth centuries. While close reading is admittedly of limited value in the study of 2 versification, a more rigorous type of statistical testing used in this study allows for reliable assessment of tendencies observed in relatively small corpora, while also making it possible to verify the significance of highly nuanced quantitative differences. -

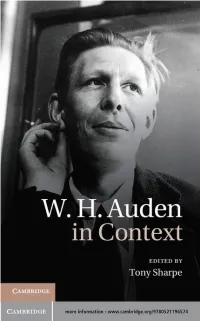

Sharpe, Tony, 1952– Editor of Compilation

more information - www.cambridge.org/9780521196574 W. H. AUDen IN COnteXT W. H. Auden is a giant of twentieth-century English poetry whose writings demonstrate a sustained engagement with the times in which he lived. But how did the century’s shifting cultural terrain affect him and his work? Written by distinguished poets and schol- ars, these brief but authoritative essays offer a varied set of coor- dinates by which to chart Auden’s continuously evolving career, examining key aspects of his environmental, cultural, political, and creative contexts. Reaching beyond mere biography, these essays present Auden as the product of ongoing negotiations between him- self, his time, and posterity, exploring the enduring power of his poetry to unsettle and provoke. The collection will prove valuable for scholars, researchers, and students of English literature, cultural studies, and creative writing. Tony Sharpe is Senior Lecturer in English and Creative Writing at Lancaster University. He is the author of critically acclaimed books on W. H. Auden, T. S. Eliot, Vladimir Nabokov, and Wallace Stevens. His essays on modernist writing and poetry have appeared in journals such as Critical Survey and Literature and Theology, as well as in various edited collections. W. H. AUDen IN COnteXT edited by TONY SharPE Lancaster University cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo, Delhi, Mexico City Cambridge University Press 32 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10013-2473, USA www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521196574 © Cambridge University Press 2013 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. -

Glossary of Poetic Terms

Glossary of Poetic Terms poetryfoundation.org/learn/glossary-terms Showing 1 to 20 of 227 Terms Browse all terms Abecedarian Related to acrostic, a poem in which the first letter of each line or stanza follows sequentially through the alphabet. See Jessica Greenbaum, “A Poem for S.” Tom Disch’s “Abecedary” adapts the principles of an abecedarian poem, while Matthea Harvey’s “The Future of Terror/The Terror of Future” sequence also uses the alphabet as an organizing principle. Poets who have used the abecedarian across whole collections include Mary Jo Bang, in The Bride of E, and Harryette Mullen, in Sleeping with the Dictionary. Accentual verse Verse whose meter is determined by the number of stressed (accented) syllables—regardless of the total number of syllables—in each line. Many Old English poems, including Beowulf, are accentual; see Ezra Pound’s modern translation of “The Seafarer.” More recently, Richard Wilbur employed this same Anglo-Saxon meter in his poem “Junk.” Traditional nursery rhymes, such as “Pat-a-cake, pat-a-cake,” are often accentual. Accentual-syllabic verse Verse whose meter is determined by the number and alternation of its stressed and unstressed syllables, organized into feet. From line to line, the number of stresses (accents) may vary, but the total number of syllables within each line is fixed. The majority of English poems from the Renaissance to the 19th century are written according to this metrical system. Acmeism An early 20th-century Russian school of poetry that rejected the vagueness and emotionality of Symbolism in favor of Imagist clarity and texture. -

W. H. Auden and Me

W. H. Auden and me 125 (`Edward', `The Twa Corbies'), `The Rime of the Ancient Mariner', `The 5 Journey of the Magi', and Auden's `O what is that sound?', simply called `Ballad' here.' The last came, somehow, with the absolute certainty of knowledge that the point of poetry was its ambiguity; that you just couldn't W. H. Auden and me know what it meant. This I must have been taught, though possibly not in that particular classroom. Is it a man or woman who speaks? Who, in answer to the question about the sound of drumming coming closer from down in the valley, says: `Only the scarlet soldiers, dear,/The soldiers coming.'? Who has betrayed whom? Who cries out `O where are you going? Stay with me here!/ Were the vows you swore deceiving, deceiving?'? Who replies: `No, I promised to love you, dear,/But I must be leaving'? These questions were discussed; we knew that there wasn't an answer to any of ... we go back them; that indeterminacy was the point of asking them. We wouldn't have to `Consider this and in our time'; put it like that. We were 15 years old. But we — probably — played about it's a key text, no doubt about it: with the questions after class, just as a year later under the influence of our A-level French set-texts we devised a wet the first garden party of the year, -your-knickers comic routine in the leisurely conversation in the bar, which the romantic poets Hugo and de Musser (`Huggo and Mussett') the fact that it is later were a seedy, down-at-heel music hall duo, doomed to play the Bingley than we think. -

Poetry Form and Experience Level HE5 – 60 CATS

Creative Writing 2 Poetry Form and Experience Level HE5 – 60 CATS This course was revised and updated by Joanna Ezekiel Open College of the Arts Redbrook Business Park Wilthorpe Road Barnsley S75 1JN Telephone: 01226 730 495 Email: [email protected] www.oca-uk.com Registered charity number: 327446 OCA is a company limited by guarantee and registered in England under number 2125674 Document control number CW2pfe130213 Copyright OCA 2010; Revised 2013 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording or otherwise – without prior permission of the publisher. Cover image: Robert Delaunay, Nude Woman Reading, 1920 Images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Additional images by OCA students and tutors unless otherwise attributed. Contents Before you start Part one Getting started Projects A short history of British poetry Modern and contemporary poetry Free verse and short poems Assignment one Part two The sonnet Projects The Petrarchan sonnet The Shakespearean sonnet Variants on the sonnet form Assignment two Part three Terza rima, villanelles and terzanelle Projects The terza rima The villanelle The terzanelle Assignment three Part four Ballads, ballades and odes Projects The ballad form The ballade The ode Assignment four Part five Blank verse, syllabics and long poems Projects Blank verse Syllabic verse Sequences and long poems Assignment five Part six Pre-assessment and creative reading commentary Pre-assessment Assignment six Appendices Glossary Before you start Welcome to Creative Writing 2: Poetry Form and Experience. Your OCA Student Handbook should be able to answer most questions about this and all other OCA courses, so keep it to hand as you work through this course. -

Metered Poetry

Metered Poetry There are two basic of poetic meter with which you should be familiar: 1) Accentual-Syllabic Verse (also called syllable stress verse) 2) Accentual Verse (also called strong-stress verse) This handout uses the following symbols for metrical scansion: / indicates a stressed syllable ˘ indicates an unstressed syllable Accentual-Syllabic Verse: Most metered poetry written in modern English uses accentual-syllabic verse. A line of accentual-syllabic verse can be described using two words (e.g. iambic pentameter). - The first word refers to a “foot,” a specific pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables. - The second word indicates how many times the foot is repeated in each line. There are several common feet: Everyday example: Iamb: ˘ / Become Trochee: / ˘ Notice Anapest: ˘ ˘ / Interrupt Dactyl: / ˘ ˘ Mulligan These four are not the only feet, but they are the most common. A more complete (and needlessly extensive) list of feet is available here: http://www.polyamory.org/~howard/Poetry/feet.html. The standard terms for the number of feet per line use Greek or Latin numerical prefixes, followed by the root word “meter.” Dimeter Two feet per line Trimeter Three feet per line Tetrameter Four feet per line Pentameter Five feet per line Hexameter Six feet per line Heptameter Seven feet per line Octameter Eight feet per line Here are some examples of putting it all together: Iambic Pentameter: That time of year thou mayst in me behold [This excerpt contains the first four lines of When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang Shakespeare’s sonnet 73. Iambic pentameter Upon those boughs which shake against the cold, is the most famous form of accentual-syllabic Bare ruined choirs, where late the sweet birds sang. -

The Rev. William Matheson and the Performance of Scottish Gaelic ‘Strophic’ Verse

THE PERFORMANCE OF SCOTTISH GAELIC ‘STROPHIC’ VERSE The Rev. William Matheson and the Performance of Scottish Gaelic ‘Strophic’ Verse V. S. BLANKENHORN ABSTRACT. The late Rev. William Matheson's lifelong fascination with the performance of Gaelic songs in so-called 'strophic' metres ultimately resulted in his recording seventeen such songs for the album Gaelic Bards and Minstrels, No. 16 in the Scottish Tradition series of recordings from the School of Scottish Studies Archive. Strophic metre, used largely for clan eulogy, elegy, and other praise-poetry in the period after the decline of the syllabic metres, is remarkable in that the final line of each stanza contrasts metrically and ornamentally with all of the preceding lines in that stanza. This article examines Matheson's sources, methodology, and performance; evaluates his rationale; and assesses the likely authenticity of his performances of six songs in which the number of lines varies from one stanza to the next. Among the many topics that engaged the late Rev. William Matheson, there can be few – with the possible exception of genealogy and clan history – that interested him more deeply than the sung performance of Gaelic poetry, in particular, of poetry that had largely ceased to be sung in living tradition. Among the types of verse that interested him particularly was that which was composed in what W. J. Watson termed ‘strophic’ metre (W. J. Watson: xlv-liv). The scholarly community first became aware of his fascination with this topic during the International Congress of Celtic Studies in 1967, at which Matheson talked about strophic verse, and demonstrated how he believed songs of this type would have been performed. -

The Structure of Verse Language

Slavistische Beiträge ∙ Band 246 (eBook - Digi20-Retro) Christine D.Tomei The Structure of Verse Language Theoretical and Experimental Research in Russian and Serbo-Croatian Syllabotonic Versification Verlag Otto Sagner München ∙ Berlin ∙ Washington D.C. Digitalisiert im Rahmen der Kooperation mit dem DFG-Projekt „Digi20“ der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, München. OCR-Bearbeitung und Erstellung des eBooks durch den Verlag Otto Sagner: http://verlag.kubon-sagner.de © bei Verlag Otto Sagner. Eine Verwertung oder Weitergabe der Texte und Abbildungen, insbesondere durch Vervielfältigung, ist ohne vorherige schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlages unzulässig. «Verlag Otto Sagner» ist ein Imprint der Kubon & Sagner GmbH. Christine D. Tomei - 9783954791965 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 03:46:48AM via free access Slavistische B e it r ä g e BEGRÜNDET VON ALOIS SCHMAUS HERAUSGEGEBEN VON HEINRICH KUNSTMANN PETER REHDER JOSEF SCHRENK REDAKTION PETER REHDER Band 246 % VERLAG OTTO SAGNER MÜNCHEN Christine D. Tomei - 9783954791965 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 03:46:48AM via free access 00050385 CHRISTINE D .TOMEI THE STRUCTURE OF VERSE LANGUAGE Theoretical and Experimental Research in Russian and Serbo-Croatian Syllabo-Tonic Versification VERLAG OTTO SAGNER • MÜNCHEN 1989 Christine D. Tomei - 9783954791965 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 03:46:48AM via free access 00050385 Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München ISBN 3-87690-447-1 © Verlag Otto Sagner, München 1989 Abteilung der Firma Kubon & Sagner, München Christine D. Tomei - 9783954791965 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 03:46:48AM via free access FOREWORD The present text was defended as my Doctoral dissertation at Brown University on September 12, 1986. I would like to express my deep and unending gratitude to my major advisor, Professor Victor Terras. -

Bardic Poetry, Irish Dr Mícheál Hoyne Dublin Institute for Advanced

Bardic Poetry, Irish Dr Mícheál Hoyne Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies [email protected] Word-count 2,999 Main text 'Irish Bardic Poetry' is used by modern scholars to refer to poems written in syllabic metres in a standardised literary language common to Gaelic Ireland and Scotland between c. 1200 and c. 1650. The metrical system and standardised literary language (Classical Modern Irish) were the result of a long evolution from the seventh century to the thirteenth. Bardic poetry was practised by families of learned, hereditary poets, who composed formal praise poetry for their aristocratic patrons, religious poems, and historical and genealogical verse. Depending as it did on the patronage of traditional aristocratic Gaelic society, Bardic poetry fell into disuse in the political turmoil of the seventeenth century. Besides their linguistic, literary and metrical interest, Bardic poems are an invaluable historical source which shed light on culture, politics and society in Gaelic Ireland and Scotland c. 1200-c.1650. The English term 'Bardic poetry' is a misnomer, as the verse so designated was the work, not of the comparatively unlearned poet known as the bard, but of the learned and prestigious file. A Bardic poet (file) required rigorous training in order to master both the intricate metrical rules that he was expected to observe in composing formal verse for his patron(s) and the artificial literary language in which he composed that verse. The language of formal poetry, Classical Modern Irish, was not the vernacular of any region of Ireland or Scotland, but a standardised literary language based primarily on the spoken language of Ireland c. -

Aithbhreac Inghean Coirceadail's Lament for Niall Óg Mac Néill1

A Hero's Lament: Aithbhreac inghean Coirceadail's Lament for Niall Óg mac Néill1 JOSEPH J. FLAHIVE In recent years, the lament of Aithbhreac inghean Coirceadail has not been without interest to scholars of Scottish Gaelic— and indeed to the wider field of Celtic Literature, after a long period of neglect. Some of this delay may have been Protestant religious hesitation due to the domination of the poem by the image of a rosary; in the first printed edition of it, The Rev. Thomas McLauchlan translated the unequivocal paidrín as 'jewel', only informing the reader that it was indeed a rosary in a deliberately ambiguous footnote: 'The word "paidrein", derived from "Paidir", The Lord's Prayer, really means a rosary' (McLauchlan: 126). More recent neglect has probably been because of the notorious difficulty of the manuscript in which it is preserved rather than the nature of the text. It should suffice to begin with a brief summary of the poem's background and preservation. The poem is an elegy in the Early Modern Gaelic shared by Scotland and Ireland, lamenting the decease of Niall Óg mac Néill of Gigha, the hereditary keeper of Castle Sween. It is preserved solely in that most fascinating of manuscripts, the Book of the Dean of Lismore (hereafter, BDL), an early sixteenth-century compendium of everything from the Chronicle of Fortingall to a shopping list, with much verse filling the literary distance between these genres. The Gaelic in it is written in an orthography based on Middle Scots and far removed from the conventions of Gaelic spelling. -

Alphabetical List of Entries

Alphabetical List of Entries accent confessional poetry heroic couplet accentual- syllabic verse consonance heroic verse accentual verse convention hexameter air couplet hiatus alba cross rhyme homoeoteleuton alexandrine dactyl hymn alliteration decasyllable hyperbaton ambiguity decorum hyperbole anacoluthon deixis hypotaxis and parataxis anacreontic demotion iambic anadiplosis devotional poetry idyll analogy. See METAPHOR; dialogue image SIMILE; SYMBOL diction imagery anapest dimeter indeterminacy anaphora dozens In Memoriam stanza antistrophe dramatic monologue. See internal rhyme antithesis MONOLOGUE invective antonomasia dramatic poetry irony aporia dream vision isocolon and parison apostrophe eclogue kenning assonance ekphrasis lament asyndeton elegiac distich leonine rhyme, verse audience. See PERFORMANCE elegiac stanza letter, verse. See VERSE EPISTLE ballad elegy limerick ballad meter, hymn meter elision line beat ellipsis litotes Biblical poetry. See HYMN; encomium love poetry PSALM English prosody lyric blank verse enjambment lyric sequence blason envoi madrigal blues epic masculine and feminine broken rhyme epigram metaphor burlesque. See PARODY epitaph meter caesura epithalamium metonymy canon epithet mimesis carpe diem epode mock epic, mock heroic catachresis euphony monologue catalexis eye rhyme narrative poetry catalog fabliau narrator. See PERSONA; VOICE chain rhyme foot (modern) near rhyme chiasmus form nonsense verse Christabel meter fourteener octave closure free verse octosyllable colon genre ode complaint georgic onomatopoeia -

Comparative Slavic Metrics. Evolution of Aims and Methods of Investigation

Studia Metrica et Poetica 1.2, 2014, 130–141 Comparative Slavic Metrics. Evolution of Aims and Methods of Investigation Lucylla Pszczołowska The first project to carry out international team research on comparative Slavic metrics was developed forty years ago in Warsaw, at the Institute of Literary Research of the Polish Academy of Sciences. In time, an “inter-Slavic” team was formed – a group of people joint by warm friendship who worked on the topic with genuine passion, ever broadening the scope of research. I should also mention that the atmosphere of our Warsaw meetings – working con- ferences of our team, lasting a few days – has always been special. Not only because of the absolute freedom of sharing scientific views, but also because – in spite of the fact that the composition of the team would change over the years – we have trusted each other in all respects. I would like to recall the time when the first project of Comparative Slavic Metrics was being prepared; it was – according to our first volume – “Słownik rytmiczny i sposoby jego wykorzystania” [“Rhythmical Vocabulary and Ways of Using It”]. Initiators of this first systematic team research in the field of poetics, including many Slavonic versifications were: Maria Renata Mayenowa, an expert on poetry and verse, then the Deputy Director of the Institute of Literary Research and the head of the Theoretical Poetics Unit; Maria Dłuska, Jagiellonian University professor who cooperated with the Institute, the author of an excellent, pioneering book Studia z teorii i historii wiersza polskiego [“Studies in the Theory and History of Polish Verse”]; and Roman Jakobson, a great Slavicist with enormous achievements in linguistics, history of literature and versology, who often visited Warsaw in the 60s to attend various confer- ences.