UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE the Overheard Song: Medieval Lyric in the Mixed Genre DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Satisf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reading Questions

Music 331 – Burkholder (10th edition) Reading Questions Free Advice: Begin by reading each chapter without the questions at hand. Next, read each question and begin to reread the chapter, jotting down your answers as you find the information you need. Part I: The Ancient and Medieval Worlds—Chapter 1: Music in Antiquity 1. What are the four historical traces of music from past eras? 2. What two categories of musical evidence survive from the Stone Age? 3. On what occasions did the Mesopotamians perform music? (name 4) 4. What genre did the earliest known composer write, and what might be surprising about that composer? 5. When did Babylonians begin to write down aspects of music, and what did they record? 6. What is the date of earliest known (nearly) complete piece, and what genre is it? 7. Which three instruments were most important to the ancient Greeks, & what “trace” evidence survives? 8. In what two categories did the Greeks write about music? 9. For the Greeks (not Plato), what did harmonia mean, and what did it encompass? 10. What is ethos, and how does music relate to it? 11. Which harmoniai did Plato endorse, and why? 12. Why would Aristotle have been unhappy if his son wanted to appear on American Idol or The Voice? 13. What is a tetrachord, and what are its three genera? 14. What did the word “species” mean to Cleonides (and who was he)? 15. How much ancient Greek music survives, spanning what centuries? 16. What is the Proslambanomenos of the Iastian tonos? (You can figure this out by using the tonos information on p. -

A Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature

A Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature Robert A. Taylor RESEARCH IN MEDIEVAL CULTURE Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature Medieval Institute Publications is a program of The Medieval Institute, College of Arts and Sciences Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature Robert A. Taylor MEDIEVAL INSTITUTE PUBLICATIONS Western Michigan University Kalamazoo Copyright © 2015 by the Board of Trustees of Western Michigan University All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Taylor, Robert A. (Robert Allen), 1937- Bibliographical guide to the study of the troubadours and old Occitan literature / Robert A. Taylor. pages cm Includes index. Summary: "This volume provides offers an annotated listing of over two thousand recent books and articles that treat all categories of Occitan literature from the earli- est enigmatic texts to the works of Jordi de Sant Jordi, an Occitano-Catalan poet who died young in 1424. The works chosen for inclusion are intended to provide a rational introduction to the many thousands of studies that have appeared over the last thirty-five years. The listings provide descriptive comments about each contri- bution, with occasional remarks on striking or controversial content and numerous cross-references to identify complementary studies or differing opinions" -- Pro- vided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-58044-207-7 (Paperback : alk. paper) 1. Provençal literature--Bibliography. 2. Occitan literature--Bibliography. 3. Troubadours--Bibliography. 4. Civilization, Medieval, in literature--Bibliography. -

Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Van Oort, Danielle, "Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 1016. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REST, SWEET NYMPHS: PASTORAL ORIGINS OF THE ENGLISH MADRIGAL A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Music History and Literature by Danielle Van Oort Approved by Dr. Vicki Stroeher, Committee Chairperson Dr. Ann Bingham Dr. Terry Dean, Indiana State University Marshall University May 2016 APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Danielle Van Oort, affirm that the thesis, Rest Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the School of Music and Theatre and the College of Arts and Media. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. With our signatures, we approve the manuscript for publication. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express appreciation and gratitude to the faculty and staff of Marshall University’s School of Music and Theatre for their continued support. -

Eighteenth-Century English and French Landscape Painting

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2018 Common ground, diverging paths: eighteenth-century English and French landscape painting. Jessica Robins Schumacher University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Schumacher, Jessica Robins, "Common ground, diverging paths: eighteenth-century English and French landscape painting." (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3111. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/3111 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMON GROUND, DIVERGING PATHS: EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH AND FRENCH LANDSCAPE PAINTING By Jessica Robins Schumacher B.A. cum laude, Vanderbilt University, 1977 J.D magna cum laude, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville, 1986 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art (C) and Art History Hite Art Department University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2018 Copyright 2018 by Jessica Robins Schumacher All rights reserved COMMON GROUND, DIVERGENT PATHS: EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH AND FRENCH LANDSCAPE PAINTING By Jessica Robins Schumacher B.A. -

Baudelaire and the Rival of Nature: the Conflict Between Art and Nature in French Landscape Painting

BAUDELAIRE AND THE RIVAL OF NATURE: THE CONFLICT BETWEEN ART AND NATURE IN FRENCH LANDSCAPE PAINTING _______________________________________________________________ A Thesis Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board _______________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS _______________________________________________________________ By Juliette Pegram January 2012 _______________________ Dr. Therese Dolan, Thesis Advisor, Department of Art History Tyler School of Art, Temple University ABSTRACT The rise of landscape painting as a dominant genre in nineteenth century France was closely tied to the ongoing debate between Art and Nature. This conflict permeates the writings of poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire. While Baudelaire scholarship has maintained the idea of the poet as a strict anti-naturalist and proponent of the artificial, this paper offers a revision of Baudelaire‟s relation to nature through a close reading across his critical and poetic texts. The Salon reviews of 1845, 1846 and 1859, as well as Baudelaire‟s Journaux Intimes, Les Paradis Artificiels and two poems that deal directly with the subject of landscape, are examined. The aim of this essay is to provoke new insights into the poet‟s complex attitudes toward nature and the art of landscape painting in France during the middle years of the nineteenth century. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to Dr. Therese Dolan for guiding me back to the subject and writings of Charles Baudelaire. Her patience and words of encouragement about the writing process were invaluable, and I am fortunate to have had the opportunity for such a wonderful writer to edit and review my work. I would like to thank Dr. -

Songs in Fixed Forms

Songs in Fixed Forms by Margaret P. Hasselman 1 Introduction Fourteenth century France saw the development of several well-defined song structures. In contrast to the earlier troubadours and trouveres, the 14th-century songwriters established standardized patterns drawn from dance forms. These patterns then set up definite expectations in the listeners. The three forms which became standard, which are known today by the French term "formes fixes" (fixed forms), were the virelai, ballade and rondeau, although those terms were rarely used in that sense before the middle of the 14th century. (An older fixed form, the lai, was used in the Roman de Fauvel (c. 1316), and during the rest of the century primarily by Guillaume de Machaut.) All three forms make use of certain basic structural principles: repetition and contrast of music; correspondence of music with poetic form (syllable count and rhyme); couplets, in which two similar phrases or sections end differently, with the second ending more final or "closed" than the first; and refrains, where repetition of both words and music create an emphatic reference point. Contents • Definitions • Historical Context • Character and Provenance, with reference to specific examples • Notes and Selected Bibliography Definitions The three structures can be summarized using the conventional letters of the alphabet for repeated sections. Upper-case letters indicate that both text and music are identical. Lower-case letters indicate that a section of music is repeated with different words, which necessarily follow the same poetic form and rhyme-scheme. 1. Virelai The virelai consists of a refrain; a contrasting verse section, beginning with a couplet (two halves with open and closed endings), and continuing with a section which uses the music and the poetic form of the refrain; and finally a reiteration of the refrain. -

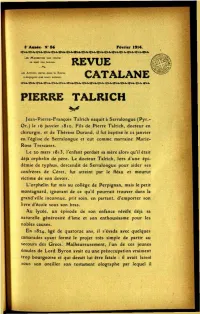

Revue Catalane Pierre Talrich

8' AMCC. H' 86 Février 1914. -es MïntBcrKS non ti»cTci ne sont oas rtnau.. REVUE Arttcio parus oan» u Revue n cn^igcni auc icurs auteur*. CATALANE PIERRE TALRICH Jean-Pierre-François Talrich naquit à Serralongue (Pyr.- Or.) le 16 janvier 1810. Fils de Pierre Talrich, docteur en chirurgie, et de Thérèse Durand, il fut baptisé le 22 janvier en l'église de Serralongue et eut comme marraine Marie- Rose Trescases. Le 20 mars 1813. l'enfant perdait sa mère alors qu'il était déjà orphelin de père. Le docteur Talrich, lors d'une épi• démie de typhus, descendit de Serralongue pour aider ses confrères de Céret, fut atteint par le fléau et mourut victime de son devoir. L'orphelin fut mis au collège de Perpignan, mais le petit montagnard, ignorant de ce qu'il pourrait trouver dans la grand'ville inconnue, prit soin, en partant, d'emporter son livre d'école sous son bras. Au lycée, un épisode de son enfance révèle déjà sa naturelle générosité d'âme et son enthousiasme pour les nobles causes. En 1824, âgé de quatorze ans, il s'évada avec quelques camarades ayant formé le projet très simple de partir au secours des Grecs. Malheureusement, l'un de ces jeunes émules de Lord Byron avait eu une préoccupation vraiment trop bourgeoise et qui devait lui être fatale : il avait laissé sous son oreiller son testament olographe par lequel il - 34 - déshéritait, en bonne et due forme, son neveu qui lui avait, quelques jours auparavant, administré une très irrespec• tueuse raclée. Ce document faisait connaître les intentions des futurs guerriers. -

The Logic of the Grail in Old French and Middle English Arthurian Romance

The Logic of the Grail in Old French and Middle English Arthurian Romance Submitted in part fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Martha Claire Baldon September 2017 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 8 Introducing the Grail Quest ................................................................................................................ 9 The Grail Narratives ......................................................................................................................... 15 Grail Logic ........................................................................................................................................ 30 Medieval Forms of Argumentation .................................................................................................. 35 Literature Review ............................................................................................................................. 44 Narrative Structure and the Grail Texts ............................................................................................ 52 Conceptualising and Interpreting the Grail Quest ............................................................................ 64 Chapter I: Hermeneutic Progression: Sight, Knowledge, and Perception ............................... 78 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... -

Apollinaire's Verse Without Borders In

Bories, A-S 2019 Sex, Wine and Statelessness: Apollinaire’s Verse without Borders in ‘Vendémiaire’. Modern Languages Open, 2019(1): 14 pp. 1–13. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3828/mlo.v0i0.221 ARTICLES – FRENCH AND FRANCOPHONE Sex, Wine and Statelessness: Apollinaire’s Verse without Borders in ‘Vendémiaire’ Anne-Sophie Bories Universität Basel, CH [email protected] Guillaume Apollinaire is a perfect stateless European. Originally a subject of the Russian Empire, born Wilhelm Kostrowicky in Rome to a Finland-born, Polish-Italian single mother, later becoming a prominent French poet and a soldier and even- tually being granted much-desired French nationality, his biography reads like a novel. His 174-line poem ‘Vendémiaire’ (Alcools, 1913) is titled after the French Revolutionary Calendar’s windy month of grape harvest, and as such centres on wine. In this ‘chanson de Paris’, a personified Paris’ thirst for wine is met by the enthusiastic response of multiple towns and rivers, their water changed to wine, offering themselves to the capital in an orgy-like feast. This glorification of Apollinaire’s adoptive city mixes sexual double meanings with religious refer- ences, founding a half-parodic new religion. It also touches on the poet’s own painful strangeness, which leads him to dream of a liberated, borderless world of ‘universelle ivrognerie’, in which a godlike poet creates the world anew from primordial wine, and which also links to issues of national and cultural identities. This exceptionally dense poem, in which several meanings, tones and verse forms overlap, provides an exemplary specimen of Apollinaire’s daring versification, which bears an important role in the construction and circulation of meaning, and is foundational to his prominence as a modernist poet. -

![Bernart De Ventadorn [De Ventador, Del Ventadorn, De Ventedorn] (B](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6126/bernart-de-ventadorn-de-ventador-del-ventadorn-de-ventedorn-b-1026126.webp)

Bernart De Ventadorn [De Ventador, Del Ventadorn, De Ventedorn] (B

Bernart de Ventadorn [de Ventador, del Ventadorn, de Ventedorn] (b Ventadorn, ?c1130–40; d ?Dordogne, c1190–1200). Troubadour. He is widely regarded today as perhaps the finest of the troubadour poets and probably the most important musically. His vida, which contains many purely conventional elements, states that he was born in the castle of Ventadorn in the province of Limousin, and was in the service of the Viscount of Ventadorn. In Lo temps vai e ven e vire (PC 70.30, which survives without music), he mentioned ‘the school of Eble’ (‘l'escola n'Eblo’) – apparently a reference to Eble II, Viscount of Ventadorn from 1106 to some time after 1147. It is uncertain, however, whether this reference is to Eble II or his son and successor Eble III; both were known as patrons of many troubadours, and Eble II was himself a poet, although apparently none of his works has survived. The reference is thought to indicate the existence of two competing schools of poetic composition among the early troubadours, with Eble II as the head and patron of the school that upheld the more idealistic view of courtly love against the propagators of the trobar clos or difficult and dark style. Bernart, according to this hypothesis, became the principal representative of this idealist school among the second generation of troubadours. The popular story of Bernart's humble origins stems also from his vida and from a satirical poem by his slightly younger contemporary Peire d'Alvernhe. The vida states that his father was either a servant, a baker or a foot soldier (in Peire's version, a ‘worthy wielder of the laburnum bow’), and his mother either a servant or a baker (Peire: ‘she fired the oven and gathered twigs’). -

Sachgebiete Im Überblick 513

Sachgebiete im Überblick 513 Sachgebiete im Überblick Dramatik (bei Verweis-Stichwörtern steht in Klammern der Grund artikel) Allgemelnes: Aristotel. Dramatik(ep. Theater)· Comedia · Comedie · Commedia · Drama · Dramaturgie · Furcht Lyrik und Mitleid · Komödie · Libretto · Lustspiel · Pantragis mus · Schauspiel · Tetralogie · Tragik · Tragikomödie · Allgemein: Bilderlyrik · Gedankenlyrik · Gassenhauer· Tragödie · Trauerspiel · Trilogie · Verfremdung · Ver Gedicht · Genres objectifs · Hymne · Ideenballade · fremdungseffekt Kunstballade· Lied· Lyrik· Lyrisches Ich· Ode· Poem · Innere und äußere Strukturelemente: Akt · Anagnorisis Protestsong · Refrain · Rhapsodie · Rollenlyrik · Schlager · Aufzug · Botenbericht · Deus ex machina · Dreiakter · Formale Aspekte: Bildreihengedicht · Briefgedicht · Car Drei Einheiten · Dumb show · Einakter · Epitasis · Erre men figuratum (Figurengedicht) ·Cento· Chiffregedicht· gendes Moment · Exposition · Fallhöhe · Fünfakter · Göt• Echogedicht· Elegie · Figur(en)gedicht · Glosa · Klingge terapparat · Hamartia · Handlung · Hybris · Intrige · dicht . Lautgedicht . Sonett · Spaltverse · Vers rapportes . Kanevas · Katastasis · Katastrophe · Katharsis · Konflikt Wechselgesang · Krisis · Massenszenen · Nachspiel · Perioche · Peripetie Inhaltliche Aspekte: Bardendichtung · Barditus · Bildge · Plot · Protasis · Retardierendes Moment · Reyen · Spiel dicht · Butzenscheibenlyrik · Dinggedicht · Elegie · im Spiel · Ständeklausel · Szenarium · Szene · Teichosko Gemäldegedicht · Naturlyrik · Palinodie · Panegyrikus -

"Theater and Empire: a History of Assumptions in the English-Speaking Atlantic World, 1700-1860"

"THEATER AND EMPIRE: A HISTORY OF ASSUMPTIONS IN THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING ATLANTIC WORLD, 1700-1860" BY ©2008 Douglas S. Harvey Submitted to the graduate degree program in History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ____________________________________ Chairperson Committee Members* ___________________________________* ___________________________________* ___________________________________* ___________________________________* Date Defended: April 7, 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Douglas S. Harvey certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: "THEATER AND EMPIRE: A HISTORY OF ASSUMPTIONS IN THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING ATLANTIC WORLD, 1700-1860" Committee ____________________________________ Chairperson ___________________________________* ___________________________________* ___________________________________* ___________________________________* Date Approved: April 7, 2008 ii Abstract It was no coincidence that commercial theater, a market society, the British middle class, and the “first” British Empire arose more or less simultaneously. In the seventeenth century, the new market economic paradigm became increasingly dominant, replacing the old feudal economy. Theater functioned to “explain” this arrangement to the general populace and gradually it became part of what I call a “culture of empire” – a culture built up around the search for resources and markets that characterized imperial expansion. It also rationalized the depredations the Empire brought to those whose resources and labor were coveted by expansionists. This process intensified with the independence of the thirteen North American colonies, and theater began representing Native Americans and African American populations in ways that rationalized the dominant society’s behavior toward them. By utilizing an interdisciplinary approach, this research attempts to advance a more nuanced and realistic narrative of empire in the early modern and early republic periods.