(D. 1212), a Chan Buddhist Layman of the Southern Song Alan Wagner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Samlekhana Is a Step Towards Self-Realization

National Seminar on BIO ETHICS - 24th & 25th Jan. 2007 31 Samlekhana is a Step Towards Self-realization Utpala Mody H-402, Vishal Apt, Sir M. V. Road, Andheri (E), Mumbai-400 069. Email: [email protected] Introduction by the rules of conduct, are liable to be caught in the wheel of Samsara. Such persons are caught in the In the present political life of our country, fast moha-dharma. Fasting unto death for specific unto death for specific ends has been very common. purposes has an element of coercion, which is against The Manusmruti mentions some traditional methods the spirit of non-violence. of fasting unto death in order to get back the loan that was once given. The Rajatarangi refers to In addition to the twelve vratas a householder Brahmins resorting to fast in order to obtain justice is expected to practice in the last moment of his life or protest against abuses. Religious suicide is the process of samlekhana, i.e. peaceful or voluntary occasionally commended by the Hindus. With a vow death. A layman is expected not only to live a to some deity they starve themselves to death, enter disciplined life but also to die bravely a detached death. fire and throw themselves down a precipice. Samlekhana, generally interpreted as ritual Society and religions in the past approved suicide by fasting, the scraping or emaciating of the different forms of voluntary deaths as acts of piety, kasayas, forms the subject of a vrata which, since it conducive to religious merit. Sometimes such acts cannot by its nature be included among the formal have been condemned as repugnant to all morals and religious obligations, is treated as supplementary to human conscience. -

Just This Is It: Dongshan and the Practice of Suchness / Taigen Dan Leighton

“What a delight to have this thorough, wise, and deep work on the teaching of Zen Master Dongshan from the pen of Taigen Dan Leighton! As always, he relates his discussion of traditional Zen materials to contemporary social, ecological, and political issues, bringing up, among many others, Jack London, Lewis Carroll, echinoderms, and, of course, his beloved Bob Dylan. This is a must-have book for all serious students of Zen. It is an education in itself.” —Norman Fischer, author of Training in Compassion: Zen Teachings on the Practice of Lojong “A masterful exposition of the life and teachings of Chinese Chan master Dongshan, the ninth century founder of the Caodong school, later transmitted by Dōgen to Japan as the Sōtō sect. Leighton carefully examines in ways that are true to the traditional sources yet have a distinctively contemporary flavor a variety of material attributed to Dongshan. Leighton is masterful in weaving together specific approaches evoked through stories about and sayings by Dongshan to create a powerful and inspiring religious vision that is useful for students and researchers as well as practitioners of Zen. Through his thoughtful reflections, Leighton brings to light the panoramic approach to kōans characteristic of this lineage, including the works of Dōgen. This book also serves as a significant contribution to Dōgen studies, brilliantly explicating his views throughout.” —Steven Heine, author of Did Dōgen Go to China? What He Wrote and When He Wrote It “In his wonderful new book, Just This Is It, Buddhist scholar and teacher Taigen Dan Leighton launches a fresh inquiry into the Zen teachings of Dongshan, drawing new relevance from these ancient tales. -

Umithesis Lye Feedingghosts.Pdf

UMI Number: 3351397 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ______________________________________________________________ UMI Microform 3351397 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. _______________________________________________________________ ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vi INTRODUCTION The Yuqie yankou – Present and Past, Imagined and Performed 1 The Performed Yuqie yankou Rite 4 The Historical and Contemporary Contexts of the Yuqie yankou 7 The Yuqie yankou at Puti Cloister, Malaysia 11 Controlling the Present, Negotiating the Future 16 Textual and Ethnographical Research 19 Layout of Dissertation and Chapter Synopses 26 CHAPTER ONE Theory and Practice, Impressions and Realities 37 Literature Review: Contemporary Scholarly Treatments of the Yuqie yankou Rite 39 Western Impressions, Asian Realities 61 CHAPTER TWO Material Yuqie yankou – Its Cast, Vocals, Instrumentation -

Ratnakarandaka-F-With Cover

Ācārya Samantabhadra’s Ratnakaraõçaka-śrāvakācāra – The Jewel-casket of Householder’s Conduct vkpk;Z leUrHkæ fojfpr jRudj.MdJkodkpkj Divine Blessings: Ācārya 108 Vidyānanda Muni VIJAY K. JAIN Ācārya Samantabhadra’s Ratnakaraõçaka-śrāvakācāra – The Jewel-casket of Householder’s Conduct vkpk;Z leUrHkæ fojfpr jRudj.MdJkodkpkj Ācārya Samantabhadra’s Ratnakaraõçaka-śrāvakācāra – The Jewel-casket of Householder’s Conduct vkpk;Z leUrHkæ fojfpr jRudj.MdJkodkpkj Divine Blessings: Ācārya 108 Vidyānanda Muni Vijay K. Jain fodYi Front cover: Depiction of the Holy Feet of the twenty-fourth Tīrthaôkara, Lord Mahāvīra, at the sacred hills of Shri Sammed Shikharji, the holiest of Jaina pilgrimages, situated in Jharkhand, India. Pic by Vijay K. Jain (2016) Ācārya Samantabhadra’s Ratnakaraõçaka-śrāvakācāra – The Jewel-casket of Householder’s Conduct Vijay K. Jain Non-Copyright This work may be reproduced, translated and published in any language without any special permission provided that it is true to the original and that a mention is made of the source. ISBN 81-903639-9-9 Rs. 500/- Published, in the year 2016, by: Vikalp Printers Anekant Palace, 29 Rajpur Road Dehradun-248001 (Uttarakhand) India www.vikalpprinters.com E-mail: [email protected] Tel.: (0135) 2658971 Printed at: Vikalp Printers, Dehradun (iv) eaxy vk'khokZn & ijeiwT; fl¼kUrpØorhZ 'osrfiPNkpk;Z Jh fo|kuUn th eqfujkt milxsZ nq£Hk{ks tjfl #tk;ka p fu%izfrdkjs A /ekZ; ruqfoekspuekgq% lYys[kukek;kZ% AA 122 AA & vkpk;Z leUrHkæ] jRudj.MdJkodkpkj vFkZ & tc dksbZ fu"izfrdkj milxZ] -

The Usage of the Chinese Traditional “Yun Wen”

Research on Symbol Expression for Eye Image in Product Design: The Usage of the Chinese Traditional “Yun Wen” Chi-Chang Lu1 and Po-Hsien Lin2 1 Crafts and Design Department, National Taiwan University of Arts Ban Ciao City, Taipei 22058, Taiwan 2 Graduate School of Creative Industry Design, National Taiwan University of ArtsBan Ciao City, Taipei 22058, Taiwan {t0134,t0131}@ntua.edu.tw Abstract. In visual arts, using the eyes to deliver the message of life and emo- tion of a living thing has always been emphasized. The expression of the eyes is usually a combination of the eyeballs, pupils, eyelids, and eyelashes, etc. Among these, the pupil is of a crucial character. It completes the image of an eye and shows the direction of the line of sight. In this article, the authors wish to create a new way to show the symbols of eyes based on the Chinese tradi- tional cloud pattern- Yun Wen in the area of the product design. The design will combine the features of both the traditional cultural style and the vogue. It will also present the eastern aesthetics difference between visual similarity and visu- al dissimilarity. Keywords: Clouds pattern (Yun Wen), Chinese traditional pattern, decoration, eye image, cultural implication, product design. 1 Introduction At a product design event, the first author exhibited a teapot based on the form of the Chinese Prehistoric Pottery Gui-tripod. The Chinese traditional clouds pattern - Yun Wen- was selected for the symbolic decoration of a bird’s crest and wing to incorpo- rate extra traditional cultural elements into the design. -

Excerpts for Distribution

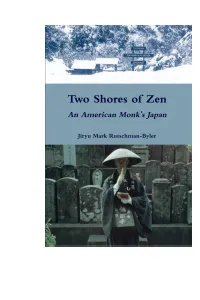

EXCERPTS FOR DISTRIBUTION Two Shores of Zen An American Monk’s Japan _____________________________ Jiryu Mark Rutschman-Byler Order the book at WWW.LULU.COM/SHORESOFZEN Join the conversation at WWW.SHORESOFZEN.COM NO ZEN IN THE WEST When a young American Buddhist monk can no longer bear the pop-psychology, sexual intrigue, and free-flowing peanut butter that he insists pollute his spiritual community, he sets out for Japan on an archetypal journey to find “True Zen,” a magical elixir to relieve all suffering. Arriving at an austere Japanese monastery and meeting a fierce old Zen Master, he feels confirmed in his suspicion that the Western Buddhist approach is a spineless imitation of authentic spiritual effort. However, over the course of a year and a half of bitter initiations, relentless meditation and labor, intense cold, brutal discipline, insanity, overwhelming lust, and false breakthroughs, he grows disenchanted with the Asian model as well. Finally completing the classic journey of the seeker who travels far to discover the home he has left, he returns to the U.S. with a more mature appreciation of Western Buddhism and a new confidence in his life as it is. Two Shores of Zen weaves together scenes from Japanese and American Zen to offer a timely, compelling contribution to the ongoing conversation about Western Buddhism’s stark departures from Asian traditions. How far has Western Buddhism come from its roots, or indeed how far has it fallen? JIRYU MARK RUTSCHMAN-BYLER is a Soto Zen priest in the lineage of Shunryu Suzuki Roshi. He has lived in Buddhist temples and monasteries in the U.S. -

Bridging Worlds: Buddhist Women's Voices Across Generations

BRIDGING WORLDS Buddhist Women’s Voices Across Generations EDITED BY Karma Lekshe Tsomo First Edition: Yuan Chuan Press 2004 Second Edition: Sakyadhita 2018 Copyright © 2018 Karma Lekshe Tsomo All rights reserved No part of this book may not be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage or retreival system, without the prior written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations. Cover Illustration, "Woman on Bridge" © 1982 Shig Hiu Wan. All rights reserved. "Buddha" calligraphy ©1978 Il Ta Sunim. All rights reserved. Chapter Illustrations © 2012 Dr. Helen H. Hu. All rights reserved. Book design and layout by Lillian Barnes Bridging Worlds Buddhist Women’s Voices Across Generations EDITED BY Karma Lekshe Tsomo 7th Sakyadhita International Conference on Buddhist Women With a Message from His Holiness the XIVth Dalai Lama SAKYADHITA | HONOLULU, HAWAI‘I iv | Bridging Worlds Contents | v CONTENTS MESSAGE His Holiness the XIVth Dalai Lama xi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xiii INTRODUCTION 1 Karma Lekshe Tsomo UNDERSTANDING BUDDHIST WOMEN AROUND THE WORLD Thus Have I Heard: The Emerging Female Voice in Buddhism Tenzin Palmo 21 Sakyadhita: Empowering the Daughters of the Buddha Thea Mohr 27 Buddhist Women of Bhutan Tenzin Dadon (Sonam Wangmo) 43 Buddhist Laywomen of Nepal Nivedita Kumari Mishra 45 Himalayan Buddhist Nuns Pacha Lobzang Chhodon 59 Great Women Practitioners of Buddhadharma: Inspiration in Modern Times Sherab Sangmo 63 Buddhist Nuns of Vietnam Thich Nu Dien Van Hue 67 A Survey of the Bhikkhunī Saṅgha in Vietnam Thich Nu Dong Anh (Nguyen Thi Kim Loan) 71 Nuns of the Mendicant Tradition in Vietnam Thich Nu Tri Lien (Nguyen Thi Tuyet) 77 vi | Bridging Worlds UNDERSTANDING BUDDHIST WOMEN OF TAIWAN Buddhist Women in Taiwan Chuandao Shih 85 A Perspective on Buddhist Women in Taiwan Yikong Shi 91 The Inspiration ofVen. -

Chinese Models for Chōgen's Pure Land Buddhist Network

Chinese Models for Chōgen’s Pure Land Buddhist Network Evan S. Ingram Chinese University of Hong Kong The medieval Japanese monk Chōgen 重源 (1121–1206), who so- journed at several prominent religious institutions in China during the Southern Song, used his knowledge of Chinese religious social or- ganizations to assist with the reconstruction of Tōdaiji 東大寺 after its destruction in the Gempei 源平 Civil War. Chōgen modeled the Buddhist societies at his bessho 別所 “satellite temples,” located on estates that raised funds and provided raw materials for the Tōdaiji reconstruction, upon the Pure Land societies that financed Tiantai天 台 temples in Ningbo 寧波 and Hangzhou 杭州. Both types of societ- ies formed as responses to catastrophes, encouraged diverse mem- berships of lay disciples and monastics, constituted geographical networks, and relied on a two-tiered structure. Also, Chōgen devel- oped Amidabutsu 阿弥陀仏 affiliation names similar in structure and function to those used by the “People of the Way” (daomin 道民) and other lay religious groups in southern China. These names created a collective identity for Chōgen’s devotees and established Chōgen’s place within a lineage of important Tōdaiji persons with the help of the Hishō 祕鈔, written by a Chōgen disciple. Chōgen’s use of religious social models from China were crucial for his fundraising and leader- ship of the managers, architects, sculptors, and workmen who helped rebuild Tōdaiji. Keywords: Chogen, Todaiji, Song Buddhism, Pure Land Buddhism, Pure Land society he medieval Japanese monk Chōgen 重源 (1121–1206) earned Trenown in his middle years as “the monk who traveled to China on three occasions,” sojourning at several of the most prominent religious institutions of the Southern Song (1127–1279), including Tiantaishan 天台山 and Ayuwangshan 阿育王山. -

What Is a Koan

WHAT IS A KOAN AND WHAT DO YOU DO WITH IT? Jeff Shore Koan practice is a catalyst to awaken as Gautama Buddha did. Early Chan (Chinese Zen) encounters and statements are precursors of koans. Eventually these impromptu encounters and statements led to the practice of focusing on the koan as one’s own deepest question. The point is to directly awaken no-self, or being without self. This was done through rousing the basic religious problem known as great doubt. This doubt calls into question the very nature of one’s being, and that of all others. Over time, koan cases and commentaries developed to explore and express awakening from a dream world or nightmare of isolation and opposition. Particularly in Japan, koan curricula developed to foster awakening and to refine it in all aspects of life. Scholars have examined koan practice in light of its history, texts, social and political contexts, and sectarian conflicts. The aim here is to clarify what koans are and how they are used in authentic practice. The koan tradition arose out of encounters between teachers and disciples in Tang Dynasty (618-907) China. The koans now used in monastic training and in lay groups worldwide grew out of this tradition. Admirers tend to consider koan practice a unique and peerless spiritual treasure. Critics see koan practice as little more than a hollow shell. There are good reasons for both views. By inviting readers to directly open up to their own great doubt, this paper provides a sense of what koan practice is from the inside. -

Zen Masters at Play and on Play: a Take on Koans and Koan Practice

ZEN MASTERS AT PLAY AND ON PLAY: A TAKE ON KOANS AND KOAN PRACTICE A thesis submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Brian Peshek August, 2009 Thesis written by Brian Peshek B.Music, University of Cincinnati, 1994 M.A., Kent State University, 2009 Approved by Jeffrey Wattles, Advisor David Odell-Scott, Chair, Department of Philosophy John R.D. Stalvey, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements iv Chapter 1. Introduction and the Question “What is Play?” 1 Chapter 2. The Koan Tradition and Koan Training 14 Chapter 3. Zen Masters At Play in the Koan Tradition 21 Chapter 4. Zen Doctrine 36 Chapter 5. Zen Masters On Play 45 Note on the Layout of Appendixes 79 APPENDIX 1. Seventy-fourth Koan of the Blue Cliff Record: 80 “Jinniu’s Rice Pail” APPENDIX 2. Ninty-third Koan of the Blue Cliff Record: 85 “Daguang Does a Dance” BIBLIOGRAPHY 89 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are times in one’s life when it is appropriate to make one’s gratitude explicit. Sometimes this task is made difficult not by lack of gratitude nor lack of reason for it. Rather, we are occasionally fortunate enough to have more gratitude than words can contain. Such is the case when I consider the contributions of my advisor, Jeffrey Wattles, who went far beyond his obligations in the preparation of this document. From the beginning, his nurturing presence has fueled the process of exploration, allowing me to follow my truth, rather than persuading me to support his. -

1 JOY CECILE BRENNAN Assistant Professor of Religious Studies

JOY CECILE BRENNAN Assistant Professor of Religious Studies Kenyon College O’Connor House 204 [email protected] Employment 2015 – present Assistant Professor of Religious Studies, Kenyon College 2014 – 2015 Visiting Instructor of Religious Studies, Kenyon College 2013 Instructor, Humanities Core, University of Chicago 2010 – 2013 Instructor, Writing Program, University of Chicago 2012 Adjunct Instructor of Religious Studies, Elmhurst College Education 2015 Ph.D., Philosophy of Religions, University of Chicago 2007 M.A., Religious Studies, Indiana University 2002 B.A., Philosophy, summa cum laude with honors, Fordham University Publications Essays and Manuscripts in Progress “Mind Only and Dharmas in Vasubandhu’s Twenty Verses” (research complete, manuscript in progress, submission to the Journal of Buddhist Philosophy anticipated in fall of 2020) Mind Only on the Path: Centering Liberation in Yogācāra Buddhist Thought (book manuscript, anticipated completion in fall of 2021) Articles and Essays “Out of the Abyss: On Pedagogical Relationality and Time in Confessions and the Lotus Sutra” (forthcoming in Augustine and Time, edited by Kim Paffenroth and Sean Hannan, Rowman and Littlefield, 2020) “Who Practices the Path? Persons and Dharmas in Mind Only Thought.” In Reasons and Lives in Buddhist Traditions, edited by Dan Arnold, Cécile Ducher and Pierre- Julien Harter; Wisdom Publications (2019). “A Buddhist Phenomenology of the White Mind.” In Buddhism and Whiteness: Critical Reflections, edited by George Yancy and Emily McRae; Rowman and Littlefield 1 (2019). “The Three Natures and the Path to Liberation in Yogācāra-Vijñānavāda Thought.” Journal of Indian Philosophy 46:4 (September, 2018): 621-648. Reviews Roy Tzohar. A Yogācāra Buddhist Theory of Metaphor. Journal of Buddhist Ethics 27 (January 2020). -

Pure Mind, Pure Land a Brief Study of Modern Chinese Pure Land Thought and Movements

Pure Mind, Pure Land A Brief Study of Modern Chinese Pure Land Thought and Movements Wei, Tao Master of Arts Faculty ofReligious Studies McGill University Montreal, Quebec, Canada July 26, 2007 In Partial Fulfillment ofthe Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Faculty ofReligious Studies of Mc Gill University ©Tao Wei Copyright 2007 All rights reserved. Library and Bibliothèque et 1+1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Bran ch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-51412-2 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-51412-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, électronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation.