Understanding Stakeholder Interactions in Urban Partnerships

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Descendants of Thomas Hodgkin

Descendants of Thomas Hodgkin Charles E. G. Pease Pennyghael Isle of Mull Descendants of Thomas Hodgkin 1-Thomas Hodgkin died on 29 Jul 1709. Thomas married Ann Alcock on 21 May 1665. Ann died on 24 Apr 1689. They had three children: Thomas, John, and Elizabeth. Noted events in their marriage were: • They had a residence in Shutford, Banbury, Oxfordshire. 2-Thomas Hodgkin was born on 29 Mar 1666 in Shutford, Banbury, Oxfordshire and died in 1740 at age 74. Thomas married Elizabeth. They had seven children: Ann, Thomas, John, Mary, Elizabeth, Hannah, and Richard. 3-Ann Hodgkin was born on 24 Dec 1696. Ann married _____ Hall. 3-Thomas Hodgkin was born on 7 Aug 1699 and died on 6 Feb 1752 in Penn's Neck, New Jersey. USA at age 52. General Notes: Emigrated to Pennsylvania. 3-John Hodgkin was born on 31 Oct 1701 in Shipston on Stour, Warwickshire and died on 9 Oct 1786 at age 84. Noted events in his life were: • Miscellaneous: Until 1931, Shipston on Stour was part of Worcestershire. John married Susanna Hitchman. They had three children: John, Susanna, and Thomas. 4-John Hodgkin1 was born on 25 May 1741, died on 31 May 1815 in Shipston on Stour, Warwickshire at age 74, and was buried on 4 Jun 1815. Noted events in his life were: • He worked as a Woolstapler in Shipston on Stour, Warwickshire. John married Elizabeth Gibbs1 on 28 Feb 1765. Elizabeth died on 29 Apr 1805. They had five children: John, Susanna, Mary, Elizabeth, and Anna. 5-John Hodgkin1,2,3 was born on 11 Feb 1766 in Shipston on Stour, Warwickshire and died on 29 Sep 1845 in Tottenham, London at age 79. -

Network Preferences and the Growth of the British Cotton Textile Industry, C.1780-1914

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Munich Personal RePEc Archive MPRA Munich Personal RePEc Archive Network preferences and the growth of the British cotton textile industry, c.1780-1914 Steven Toms University of Leeds 6 July 2017 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/80058/ MPRA Paper No. 80058, posted 8 July 2017 14:38 UTC Network preferences and the growth of the British cotton textile industry, c.1780-1914 By Steven Toms (University of Leeds) Preliminary draft, for presentation at Association of Business Historians Conference, Glasgow, June 2017. Keywords: Business networks, British cotton textile industry, innovation, finance, regions, entrepreneurship, mergers. JEL: L14, L26, O33, N24, N83 Correspondence details: Steven Toms Professor of Accounting, Leeds University Business School Room 2.09, Maurice Keyworth Building University of Leeds Leeds LS2 9JT Tel: 44(113)-3434456 Email: [email protected] Word count: c.11,000 Abstract The paper considers the dual aspect of social networks in terms of 1) product innovators and developers and 2) the providers of finance. The growth of networks can be explained as a function of incumbents and entrants’ preferences to link with specific nodes defined according to the underlying duality. Such preferences can be used to explain network evolution and growth dynamics in the cotton textile industry, from being the first sector to develop in the industrial revolution through to its maturity. The network preference approach potentially explains several features of the long run industry life cycle: 1. The early combination of innovators with access to extensive credit networks, protected by entry barriers determined by pre-existing network structures, leading to lower capital costs for incumbents and rapid productivity growth, c.1780-1830. -

Autumn 07 Cover

ORDERS, DECORATIONS AND MEDALS 4-5 DECEMBER 2017 LONDON GROUP CHAIRMAN AND CEO Olivier D. Stocker YOUR SPECIALISTS STAMPS UK - Tim Hirsch FRPSL David Parsons Nick Startup Neill Granger FRPSL Dominic Savastano George James Ian Shapiro (Consultant) USA - George Eveleth Fernando Martínez EUROPE - Guido Craveri Fernando Martínez CHINA - George Yue (Consultant) Alan Ho COINS UK - Richard Bishop Tim Robson Gregory Edmund Robert Parkinson Lawrence Sinclair Barbara Mears John Pett (Consultant) USA - Muriel Eymery Greg Cole Stephen Gol dsmith (Special Consultant) CHINA - Kin Choi Cheung Paul Pei Po Chow BANKNOTES UK - Barnaby Faull Andrew Pattison Thomasina Smith USA - Greg Cole Stephen Goldsmith (Special Consultant) CHINA - Kelvin Cheung Paul Pei Po Chow ORDERS, DECORATIONS, MEDALS & MILITARIA UK - David Erskine-Hill Marcus Budgen USA - Greg Cole BONDS & SHARES UK - Mike Veissid (Consultant) Andrew Pattison Thomasina Smith USA - Stephen Goldsmith (Special Consultant) EUROPE - Peter Christen (Consultant) CHINA - Kelvin Cheung BOOKS UK - Emma Howard Nik von Uexkull AUTOGRAPHS USA - Greg Cole Stephen Goldsmith (Special Consultant) WINES CHINA - Angie Ihlo Fung Guillaume Willk-Fabia (Consultant) SPECIAL COMMISSIONS UK - Ian Copson Edward Hilary Davis YOUR EUROPE TEAM (LONDON - LUGANO) Directors Tim Hirsch Anthony Spink Auction & Client Management Team Mira Adusei-Poku Rita Ariete Katie Cload Dora Szigeti Nik von Uexkull Tom Hazell John Winchcombe Viola Craveri Finance Alison Bennet Marco Fiori Mina Bhagat Dennis Muriu Veronica Morris Varranan Somasundaram -

Post Office General and Trades Directory for Ayr Newton And

KYLE & CARRICK DISTRICT LIBRARIES LOCAL HISTORY COLLECTION ArJ This Book is for reference only and must not be taken from this room. Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2010 witii funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/postofficegenera189293uns I nsr ID Page. Page. >5BlBverti6cmcnts, - 181 Educational Trust Governor>i, - 25 Athletic Club, 16 Excise, 14 j^ yr Academical ^ yr Bible Society, 12 Fairs, 19 ji^yr Bums Club, •24 Golf Clubs, 15 ji^yr Cemetery, 9 Guildry of Ayr, - - . - 6- j4.yr County Club, 14 H.M. Prison, - - - - 24 ^i.yr County Hospital, 10 Harbour Trustees, - - - 6. />T Cricket Club, 16 Houses, Farms, &c., - - 199 jiyr District Road Trust, - lusiirance Offices and Agents, 19-20 - - >yr Gas Company, - - - 13 Justice of Peace Court, 7 /vr Lawn Tennis Club, - - 16 Justices of Peace, - - - 18 ia«r poet ®fHcc, - - - 27 Kirk Session, - - - - 10 Surveying Staff of G.P.O., 27 Kyle Union Poorhouse Boaid, 7 Branch Office, Ayr Docks, 27 Land Valuation (Kyle District), 9 Pillar and Wall Boxes, - 28 Lieutenancy of Ayrshire, - - 18 Parcels Post, - - - 32 Life-boat Institution, - - 14 Express Delivery, - - 41 Magisti-ates /".nd Town Council, 5 Money Orders, - - - 32 Magistrates of Newton, - - 18 Telegraph Money Oiders, - 32 Market Days, - - - - 19 - - - Postal Orders, - - 33 Masonic Lodges, . 17 Savings Bank. - - - 28 Medical Practitioners, - - 13 Rates of Postages, - - 34 Merchant Company, - - - 1^ Re-Direction, - - -34 Municipal Board of Police, - 6 Petitions to Parliament, • 35 Newspapers, - - - - -

Manchester and Stockport Branch of the Ashton Canal Walk

for the free downloadable audio tour! tour! audio downloadable free the for www.stockport.gov.uk/walkingpodcasts www.stockport.gov.uk/walkingpodcasts Visit... Visit... 7 1 The Manchester and Stockport 5. Victoria & Elisabeths Mills 5 branch of the Ashton Canal Another two major mills on the route. 7. Houldsworth Mill They have been renovated in recent years as part of the Houldsworth Village project. All that remains of the Stockport Branch of the canal The History Formerly cotton mills, originally built The largest cotton mill in the world at its time! Houldsworth Mill, established Built between 1793 and 1797. in 1874, now serving as commercial and living spaces. as Reddish Mill, was built by Sir William The Stockport and Manchester Canal, or “Lanky Cut” as it was locally known, Houldsworth in 1865. Houldsworth Mill was used throughout two centuries to bring coal, among other things, to the 2010 mills and industries alongside the cut in Gorton and Reddish. The canal, Victoria Mill, Reddish Houldsworth played a large part in the development of Reddish, which streched almost 5 miles from the Clayton junction to the outskirts establishing his mill in what was, at that time, a distinctly rural location. of Stockport town, fell prey to changes in the economy and dwindling traffic Luring people to the area with the jobs that the mill provided. He built in the early 1900’s. Allowed to deteriorate and lie derelict for many years, On the Podcast: Hear about homes for the workers to live in, as well as constructing St.Elisabeths’ the decision was made to fill the canal in during the 1960’s. -

Descendants of William Croker

Descendants of William Croker Charles E. G. Pease Pennyghael Isle of Mull Descendants of William Croker 1-William Croker William married someone. He had one son: William. 2-William Croker William married someone. He had one son: John. 3-Sir John Croker John married Agnes Churchill, daughter of Giles Churchill. They had one son: John. 4-Sir John Croker John married "The Heiress" Of Corim. They had one son: John. 5-Sir John Croker John married "The Heiress" Of Dawnay. They had one son: John. 6-Sir John Croker, son of Sir John Croker and "The Heiress" Of Dawnay, died on 14 May 1508 in Lyneham, Devon. Noted events in his life were: • Miscellaneous: Cup & Standard Bearer to King Edward IV. John married Elizabeth Yeo, daughter of Robert Yeo and Alice Walrond. They had one son: John. 7-Sir John Croker was born in 1458 in Lyneham, Devon and died about 1547 in Lyneham, Devon about age 89. John married Elizabeth Pollard, daughter of Sir Lewis Pollard and Agnes Exte. Elizabeth was born in Girleston and died on 21 May 1531 in Lyneham, Devon. They had one son: John. 8-John Croker was born in 1515 and died on 30 Jun 1560 in Lyneham at age 45. John married Elizabeth Strode, daughter of Richard Strode and Agnes Milliton. They had two children: John and Thomas. 9-John Croker was born in 1532 in Lyneham and died on 18 Nov 1614 in Lyneham at age 82. John married Agnes Servington, daughter of John Servington Of Tavistock and Agnes Arscott. They had one son: Hugh. -

The Free Library; Its History and Present Condition

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from Microsoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/freelibraryitshiOOogleiala XEbe Xtfrrarg Series EDITED BY Dr. RICHARD GARNETT I THE FREE LIBRARY Cbe Xlbratg Setles Edited, with Introductions, by Dr. RICHARD GARNETT, Keeper op Printed Books in the British Museum. I. THE FREE LIBRARY : Its History and Present Condition. By J. J. Ogle, of Bootle Free Library. Cloth. II. LIBRARY CONSTRUCTION, ARCHITEC- TURE, AND FITTINGS. By F. J. Bur- GOYNE, of the Tate Central Library, Brixton. With 141 Illustrations. Cloth. III. LIBRARY ADMINISTRATION. By J. Macfarlane, of the British Museum. Cloth. IV. PRICES OF BOOKS. By Henry B. Wheatley, of the Society of Arts. Cloth. THE FREE LIBRARY ITS HISTORY AND PRESENT CONDITION JOHN J. OGLE NEW YORK : FRANCIS P. HARPER LONDON : GEORGE ALLEN 1898 ; Z19I GENERAL INTRODUCTION The present age has received divers epithets, mostly uncomplimentary. If ever defined as the Age of Gold, this has by no means been intended in the ancient sense of an age of primitive innocence and simplicity. It has been styled the Age of Steam, the Age of Veneer, and the Age of Talk. As these dis- paraging epithets have all been affixed by itself, it may occur to some that the Age of Modesty, or at least of Penitence, might not be an inappropriate designation ; and after all, we do not apprehend that future ages will consider it so very inferior to most of its predecessors, and are sure that it will be universally preferred to the Ages of Darkness. -

London Bills

Hector Domestic Servants Mr Allen Robert Hicks Murray Rested Juniors Major Ferguson Mrs B Giddiness Skirt Envelopes Seniors Constable Snell Brigade Band Ear Mr Cannon Wages Institute Band Pacific Steam Navigation Company Henry Adams John Graham Caravan Cutioura Soap Mr Ferguson Bell Mr W T Commander Briggs Pique Sloan Liniment Usutu Typewriter Soldier Dolling Styles Barley Kernels Harriet Harry Russell Thomas Scott Dr Cassell Tablets People Mr John Jackson Mrs Gower October Bth / Straits Solid Food Dead Men Rhine Belle Isle Miller Wal Cartridges Warnham Sydney Smith | Anyone Drapery Goods Mr Tobin's Orizaba Helsingfors New Umbrellas George Percy Richards Hoskin Mr Tse Tsi Marconigram Mr Stewart Samuel Curtis Lord Castlereagh John Farrant Attention Campbell Campbell Mrs Bland Mr Trethowan Chief Dolly Co-operative Society Mrs Strain Good Alike Mrs Brooks Miss Mary Burn Hub Mr William Robertson Lidderdale Fearless Bicycle Alice Clover Janowski Stettin Boys ’ Howe Coats Robert Haydock Carefully Horniman Tea Parish Church — Billiards Second Army Corps Colne Charles — Mr Haldane Richard Martin Wallace Holyhead Middlesbrough Prince Umbrella Constable Saunders Dr J Dinizulu Agreements Lord Balfour Marble Headstones Little Pills Selections Londoner Ipyranga Miss Vining Payne's Annie Crosland Cuticura Soap Ointment Whitsuntide Early Passage C Davis Rice Puddings Mrs Townsend Chapel Choir Cock Big Aches Dawson Burrows Shooting Senator Aldrich Bill Sir John Goss Coated Stomach Dearer Colonel Bosworth Joseph Child Rub Re- Covered “ Equal Baker E Stuart -

A Short History of Willow Grove Cemetery C O N T E N T S

A Short History of WWillowillow GroveGrove CemeteryCemetery Compiled by members of Friends of Stockport Cemeteries Text by Mike Hughes Information sourced by Glennys Singleton, Mike Hughes & Sheila Robins Map of Willow Grove Cemetery This booklet has been showing Burial Sectors part-funded by the Co-operative Membership Community Fund, for which we are greatly appreciative R H i 2 J B i 3 i 6 P F K A 4 i 1 i 5 C S L D O E i 7 M i i i T REDDISH ROAD CENTRAL DRIVE i U W Y i informationboard The cover photograph of Willow Groves Roman Catholic Chapel (1957) is reproduced with the kind permission of Mr. A Hughes. A Short History of Willow Grove Cemetery C o n t e n t s 1 Introduction 4 2 The History of the Cemetery up to 1900 4 3 Burials in Willow Grove 6 4 War Graves 14 5 Recent History from 1960 18 6 Restoration & Re-development from 2004 20 7 Notes and Sources 22 This booklet is also available online at www.willowgrove.org.uk Part 1 Introduction A Short History of Willow Grove Cemetery gives a brief account of the history of the cemetery from its beginnings in 1877 until 2011. Relying on available documentary evidence the booklet recounts the growth and development of the cemetery from the purchase of the land in 1877 through the cemeterys initial popularity and its expansion, maturity and decline during the following century. A selection of notable burials is listed and the Imperial War Graves Commission record for the cemetery is given in full. -

A Comparative Study of the 1852-1857 and the 1895-1900 Parliaments

Businessmen in the House of Commons: A Comparative Study of the 1852-1857 and the 1895-1900 Parliaments BY C2009 Alexander S. Rosser Submitted to the graduate degree program in History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ___________________________________________ Victor Bailey, Chairman ___________________________________________ Theodore A. Wilson ___________________________________________ Joshua L. Rosenbloom ___________________________________________ J. C. D. Clark ___________________________________________ Thomas J. Lewin Date Defended 11 May, 2009 The Dissertation Committee for Alexander S. Rosser certifies That this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Businessmen in the House of Commons: A Comparative Study of the 1852-1857 and the 1895-1900 Parliaments Committee: ___________________________________________ Victor Bailey, Chairman ___________________________________________ Theodore A. Wilson ___________________________________________ Joshua L. Rosenbloom ___________________________________________ J. C. D. Clark ___________________________________________ Thomas J. Lewin Date Approved 11 May, 2009 2 Table of Contents Page Table of Contents 3 Acknowledgements 4 List of Tables 5 List of Abbreviations 12 Introduction 16 Chapter One Businessmen in the House of 26 Commons,1852-1857 Chapter Two Businessmen in the House of 110 Commons 1895-1900 Chapter Three Comparison and contrasts 241 between the Parliament of 1852-1857 and the Parliament of 1895-1900 Chapter Four The Wiener Thesis of 271 Late20th Century British Business Failure Endnotes 350 Bibliography 363 3 Acknowledgements This project first started many years ago as a master’s thesis under the direction of the late Professor John Stack of the University of Missouri at Kansas City. Professor Victor Bailey of the University of Kansas very graciously supported my efforts to extend the work to include a later Parliament and a detailed look at the Wiener Thesis. -

Dr.R.Garnett the Library of the University of California Los Angeles

IJBRAKYSKKll-.S DR.R.GARNETT THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES ITbe %ifrrat Series EDITED BY DR. RICHARD GARNETT I THE FREE LIBRARY Cbe Itbrarg Series EDITED, WITH INTRODUCTIONS, BY DR. RICHARD GARNETT, KEBHER OP PRINTED BOOKS IN THE BRITISH MUSEUM. I. THE FREE LIBRARY : Its History and Present Condition. By J. J. OGLE, of Bootle Free Library. Cloth. II. LIBRARY CONSTRUCTION, ARCHITEC- TURE, AND FITTINGS. By F. J. BUR- GOYNE, of the Tate Central Library, Brixton. With 141 Illustrations. Cloth. III. LIBRARY ADMINISTRATION. By J. MACFARLANE, of the British Museum. Cloth. IV. PRICES OF BOOKS. By HENRY B. WHEATLEY, of the Society of Arts. Cloth. THE FREE LIBRARY ITS HISTORY AND PRESENT CONDITION JOHN J. OGLE NEW YORK : FRANCIS P. HARPER LONDON : GEORGE ALLEN 1898 GENERAL INTRODUCTION THE present age has received divers epithets, mostly uncomplimentary. If ever defined as the Age of Gold, this has by no means been intended in the ancient sense of an age of primitive innocence and simplicity. It has been styled the Age of Steam, the Age of Veneer, and the Age of Talk. As these dis- paraging epithets have, all been affixed by itself, it may occur to some that the Age of Modesty, or at least of Penitence, might not be an inappropriate and after we do not designation ; all, apprehend that future ages will consider it so very inferior to most of its predecessors, and are sure that it will be universally preferred to the Ages of Darkness. With these, at least, it has nothing in common. -

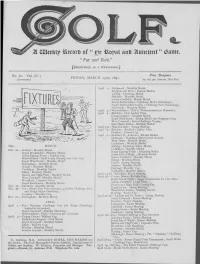

" Far and Sure.”

" Far and Sure.” [R e g is t e r e d a s a N e w s p a p e r .] No. 80. Voi. IV.] Price Twopence. FRIDAY, MARCH 25TH, 1892. [Copyright.] iOi-. 6d. per Annum, Post Free. April 2. —Richmond: Monthly Medal. Brighton and Hove : Berners Medal. Lundin : Handicap Medal. Birkdale : Monthly Medal. Sutton Coldfield : Mumly Medal. North Bedfordshire: Challenge Medal (Handicap). North Bedfordshire Ladies : Challenge Prize (Handicap). Aldeburgh : Monthly Medal. April 4.—Warwickshire : Club v. Worcestershire (at Warwick). April 5.— Birkdale : Club Ladies’ Prize. Carnarvonshire : Monthly Medal. Royal Blackheath : Spring Medal and Singapore Cup. West Cornwall: Seton Challenge Trophy. East Sheen Ladies : Monthly Medal. April 5-8.— Warwickshire : Spring Meeting. April 6.— Birkdale : Buckley’s Ladies’ Prize. Durham : Osborn Cup. April 9.— Bradford St. Andrews : Rhodes Medal. Dalhousie : Handicap Match (Sixth Round). West Herts : Monthly Medal. Littlestone : Monthly Medal. 1892. M ARCH . Didsley : Handicap Silver Medal. Guildford : Monthly Medal. Mar. 26.— Seaford : Monthly Medal. Royal Epping Forest: Quarterly Medal. Royal Wimbledon : Monthly Medal. Royal Isle of Wight : Monthly Medal. Royal Epping Forest : Gordon Cup. Sutton Coldfield : Monthly Medal. Warwickshire : Half-Yearly Meeting and Club Cup. Ealing : Monthly Medal. Royal Wimbledon : Monthly Medal. Forfar : Spring Meeting. Nottingham : Monthly Medal. Staines : Monthly Medal. Sidcup : Monthly Medal. Hayling : Monthly Cup. Crookham : Monthly Medal. Southport : Monthly Medal. Ilkley : Monthly Medal. April 14-18.—Birkdale : Easter Meeting. Buxton and High Peak : Monthly Medal. April 16.— County Down : Railway Cup. West Cornwall : Monthly Medal. Royal Isle of W igh t: Bogey Tournament for Club Prize. Woodford : Captain’s Prize. Sutton Coldfield : Lloyd Prize.